29th murderer executed in U.S. in 2000

627th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Tennesee in 2000

1st murderer executed in Tennesee since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

| Robert Glen Coe W / M / 23 - 44 |

Cary Ann Medlin W / F / 8 |

|||||||||

Summary:

Three days after 8 year old Cary Ann Medlin disappeared on September 1, 1979, Coe admitted that he had lured her into his car as she rode a bicycle near her parents' home in Greenfield, Tenn. Coe told police in handwritten and recorded statements that he sexually molested the girl, then tried to choke her, and when that did not work, stabbed her and watched her bleed to death. He also said that just before he killed her, she said to him, "Jesus loves you, Jesus loves you." Coe had a long history of family and drug abuse, repeated arrests for exposing himself in public, and had been committed to mental hospitals on four occasions prior to the murder.

Citations:

State v. Coe, 655 S.W.2d 903 (Tenn. 1983) (Direct Appeal).

Final / Special Meal:

Fried catfish, white beans, hush puppies, coleslaw, french fries, pecan pie and sweet tea.

Last Words:

"God loves you, I'm gone.''

Internet Sources:

"Tennessee Executes Coe 19 years after conviction," by Lawrence Buser. (The Commercial Appeal).

NASHVILLE - Tennessee's first execution in 40 years occurred this morning when child-killer Robert Glen Coe died of a lethal injection. The death of Coe, 44, came at 1:37 a.m. after a Nashville judge's order forbidding the execution was lifted by the Tennessee Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court gave the go-ahead for the execution.

Coe was convicted of killing Cary Ann Medlin, 8, a few miles from her Greenfield, Tenn., home on Sept. 1, 1979. ``The family of Cary Medlin is relieved and in good spirits,'' said Steve Hayes, spokesman for the Tennessee Department of Correction as he announced at 12:45 a.m. that the execution would occur.

Coe was moved to a closely monitored death watch cell at noon on Monday and on Tuesday evening had a last meal of fried catfish, white beans, hush puppies, coleslaw, french fries, pecan pie and sweet tea. Coe was given a lethal combination of drugs intervenously in both arms. Shortly before 1 a.m., Coe was strapped to a gurney and wheeled into the 15-by-20-foot execution chamber of the prison where intravenous catheters were inserted into each arm. He was given an opportunity to make a final statement before the deadly chemicals were injected. After Coe was allowed to make a final statement, Warden Ricky Bell authorized an unseen executioner in an adjoining room to begin the flow of a succession of deadly chemicals. Coe first was given sodium pentathol, a sedative to render him unconscious; then pancuronium bromide, a muscle relaxer to stop his breathing and finally potassium chloride to stop his heart.

At about 9:30 p.m. Tuesday, Davidson County Circuit Judge Thomas Brothers temporarily halted the execution, saying Coe's attorneys' argument that requiring prison health care workers to participate in the execution would mandate they violate the Hippocratic Oath that prevents them from injuring people. Because there has never been death by lethal injection in Tennessee, judges and justices were trying to determine matters of procedure as well as which judges had the authority to decide the issues raised by the defense before they ultimately gave the go-ahead for the execution. In addition to the issue of whether the prison's medical personnel should be required to participate, Brothers ruled that there was a question about whether the lethal injection procedures follow state laws governing the setting of Corrections Department policies.

Coe told authorities he killed Cary after he abducted and raped her, then heard her say ``Jesus loves you.'' The execution occurred after scores of people marked the day with remembrances of Cary and protests over the morality of the death penalty. Dozens of death penalty supporters and opponents gathered in separate sectors outside the gates of Riverbend Maximum Security Institution on the west side of town. In Memphis, protesters gathered on the steps of the Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Midtown to pray and hear speeches. Also, a special memorial service was held earlier in Nashville's Centennial Park in memory of Cary. ``We're just hoping this will bring us some closure,'' said Cary's stepfather, Mickey Stout, who witnessed the execution along with his wife, Charlotte Stout, Cary's mother.

On Tuesday morning, about two dozen anti-death penalty activists were arrested for blocking the gate in front of the Governor's Mansion. Gov. Don Sundquist, however, was vacationing in Florida. He was to return to Nashville Tuesday night prior to the execution. Late Tuesday afternoon, the U.S. Supreme Court turned down Coe's requests for a stay of execution and review of the state's competency procedures. After spending part of the afternoon saying goodbye to family members, Coe was served his last dinner.

Coe was the state's first inmate to die by lethal injection, the 126th person executed in Tennessee since 1916 and the first since 1960. Under a 1999 law, he chose lethal injection over the electric chair. He also was the 29th person executed this year in the United States and the 627th executed since 1976 when the U.S. Supreme Court lifted a four-year moratorium on capital punishment. Coe's execution leaves Tennessee's death row population at 96 inmates, including two women.

Defense attorneys had argued up to the 11th hour that Coe was delusional, psychotic and incompetent to be executed. They had won three stays of execution in the past six weeks, but all were lifted after federal courts reviewed his challenges to the state's competency procedures. Coe was born April 15, 1956, in Hickman, Ky., and lived in several small towns in Northwest Tennessee, typically in farm shacks with no running water. His sisters and brothers recalled on a defense-made videotape that the family lived in poverty and that the children often were beaten and sexually abused by their father.

"Execution is carried out after last-minute court action; Coe pronounced dead at 1:37 a.m.," by Dylan T. Lovan. (April 19, 2000)

NASHVILLE - An injection of potassium chloride into Robert Glen Coe's body at 1:37 a.m. halted the pounding of the child killer's heart and ended a 40-year moratorium on executions in this state.

Coe's death ended his 19-year appeal of a 1981 death sentence, imposed for the rape and murder of 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin, a Greenfield girl who Coe kidnapped while she was on a bike ride with her younger stepbrother. "God loves you, I'm gone,'' Coe said to his family members moments before his death. He also made what appeared to be an "I love you'' sign with his right hand. One of his family members is deaf.

But he did not admit guilt. He said that he forgave Charlotte Stout, Cary Ann's mother, for "helping the state kill him.'' "He chose his path,'' Stout said after the execution.

Following the execution, as Stout spoke, one of Coe's family members was escorted from the prison screaming. His face, published repeatedly in newspapers and broadcast on newscasts over the years, introduced a generation of Tennesseans to the stop-and-go suspense and frustration that comes when attorneys battle over a man's life.

Just four hours before the execution, Coe received a temporary reprieve and it looked like his life would be spared one more time. Davidson County Judge Thomas Brothers ruled that the state prison's lethal injection procedures were illegal. Brothers issued a restraining order and set a hearing for Thursday. But the state Supreme Court overturned Brothers' ruling less than 30 minutes before the execution was scheduled to proceed.

Some of those who have watched the drama unfold for months - fearing an imminent wave of executions after Coe's - surrounded the prison's fences just before 1 a.m., as Coe's family huddled inside a room with a pool of reporters from across Tennessee. The schedule called for a group of prison officials, called the "extraction team" strapped Coe down to a padded gurney around 12:55 a.m. just before the team wheeled the short and pudgy man, dressed in white cotton trousers and a shirt, into the death chamber. There the gurney was expected to be bolted to the floor. His Memphis attorney, Robert Hutton, who picked up the case in December to argue that Coe was too insane to kill, was scheduled to watch from a nearby room.

Catheters inserted into each of Coe's arms dripped saline to keep the hollow needles from clogging. At 1 a.m., Warden Ricky Bell gave the order to pass the drugs - sodium pentathol, pancuronium bromide and finally, potassium chloride - slowly into his veins. Coe, 44, was pronounced dead in Riverbend Maximum Security Institution's death chamber by Nashville's Metro medical examiner.

Earlier in the day, about 30 protestors gathered at the governor's mansion in Nashville, blocking the entrance. Eighteen of those protestors were arrested. Gov. Don Sundquist earlier refused clemency for Coe.

Cary Ann's mother, who has watched Coe's many appeal hearings first-hand, thought that announcement would never come. Charlotte Stout said she plans to write the final chapter of a book about her daughter soon after Coe dies. She watched as U.S. District Judge John Nixon overturned Coe's death sentence in 1996, saying that the 12-member Shelby County jury wasn't given proper instructions. That ruling was thrown out two years later by a higher court, but it would be two more years before the sentence was carried out.

A series of firsts

Coe's two-decade case brought with it a series of firsts for the death penalty in Tennessee. Not only was Coe the first inmate to die by lethal injection in this state, but he was the first to die since 1960, when William Tines was electrocuted here.

His case first tested Tennessee's new guidelines for executing mentally incompetent prisoners. Those guidelines, which were set in November and follow federal law, say prisoners who don't know what they're being killed for cannot be executed. The mental competency ruling process began in January in Shelby County, and brought Coe into a courtroom for the first time in four years.

Clothed in a white Department of Correction uniform, Coe's bald head, beady eyes and slight facial stubble made him appear older than his 43 years. Suffering from a physical illness similar to Parkinson's disease, Coe fidgeted in his shackles the first two days, but erupted on the third, spitting on a prosecutor and threatening Judge John Colton's life.

Despite the tirade, Colton ruled that while Coe exhibited a slight mental illness, he did know why he was facing execution and therefore could be killed. The State Supreme Court and two federal courts - who granted brief stays for Coe in March and April - agreed with Colton's ruling and added that the standards created in November were fair.

The claim that he was too insane to be killed - along with a plea to Gov. Don Sundquist - was Coe's real last chance of avoiding execution.

His best chance to avoid the death chamber came on Sept. 1, 1979, when he spotted Cary Ann and her step brother, Michael Stout, riding bikes in a church parking lot in Greenfield. A part-time auto mechanic who lived in nearby McKenzie, Coe had watched years before as his father raped his sisters in front of him. His father abused him, including bashing the young Coe in the head with a claw hammer. Coe later told police that as he watched from his car, he had had "the urge to flash all day." He lied and told Cary Ann he was a friend of her father's. He took her to a field where he raped her, tried to strangle her and then cut her throat with a pocketknife. Police caught up with Coe, who had died his hair black, three days later and just before he was about to board a bus in Huntingdon to leave town.

The trial was moved from Weakley to Shelby County, and in January 1981, Coe was convicted of first-degree murder, aggravated rape and kidnapping and sentenced to die.

"Family says goodbye to Robert Coe," by Kathleen Merrill. (May 1, 2000)

McKENZIE - About 30 family members and friends gathered in the sanctuary of a small church here Saturday "to celebrate the life of Robert Glen Coe," the first inmate executed in the state in 40 years. Coe's ashes sat in a black box at the foot of the pulpit, flanked by a grade school picture of an innocent young boy with an impish grin and a treasured family photo, taken about a year ago, of Coe hugging his siblings. On top of the box sat a child's drawing of a brightly crayon-colored rainbow, a picture sent to him in prison.

Coe was executed this month for raping and murdering 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin of Greenfield in 1979. But as the sun shone brightly outside the little country-style church Saturday, those inside sobbed openly and hugged each other for comfort as they recalled their brother and friend. Also in attendance was the woman who was Coe's fiance, an East Tennessee native who befriended him in September and moved to Nashville to visit Coe as often as possible in his last months alive.

"He knew we loved him, and we'll miss him with all our hearts," said his sister Billie Jean Mayberry, as tears ran down her face. She recalled that "Flubby" would break a candy bar into equal pieces for his siblings, even biting and licking them to make them the same size.

"I am sure Robert was not comfortable with his soul in this life. But I am confident that he is well with it now," said Sky McCracken of Jackson's East Trinity United Methodist Church. McCracken befriended and counseled the family in the months leading up to the execution. "There is no more fear, no more pain, no more confusion. "Even though the state of Tennessee did it, he's been given a new life," McCracken added. "I can smile because the horrible hell he lived on earth is gone, and he is with his father in heaven."

A family's burden

In an interview with The Jackson Sun after the one-hour memorial service, three of Coe's four siblings talked of their brother and the life that was shattered by abuse at the hands of their father. The family has lived in a way incomprehensible to most people, as the innocent relatives of a convicted murderer. They talked of the 21 years since Coe's arrest and the horror of watching him die by lethal injection in the middle of the night less than two weeks ago.

"There's no way to describe the hurt we had to go through when we watched him die," Mayberry said, crying. "It was different when our mother was sick and died. We had to watch them kill him."

A few of them have wavered in the past in their belief that Coe, 44, was innocent of killing Cary Ann. Still, Roger Coe (52), Jimmy Coe (49), Bonnie DeShields (45) and Mayberry (43) have stuck together through their childhood abuse, Coe's mental illness and embarrassing history of flashing, his conviction, imprisonment and execution and constant media scrutiny. They have been shot at, threatened repeatedly, shunned, fired from jobs and gossiped about through the years, because of their relationship to Coe, they said.

"If people know that you're Robert Coe's sister or brother, they don't want anything to do with you. It's like you're shut off from the world," DeShields said. "Even the ones who don't come out and say it openly, you feel like they feel like everyone else does." "But we're strong, our kids are strong and we're all standing there right with Robert," Mayberry said. "That's what a family that loves each other is supposed to do." "The one thing that got us through it is, we saw a God that loves little children, even Robert," DeShields said. "We know that the only way to have real peace is keeping our minds on God."

They feel for Cary Ann's family members, and they can understand why Charlotte Stout, Cary Ann's mother, put so much of herself into campaigning for Coe's death. But it didn't and won't solve anything, they said. "I think she's still hurting. Just because they killed my brother doesn't mean it's going to stop her pain," Mayberry said through tears. "I can't put myself in her shoes; I wouldn't want to. But we hurt right along with her."

Questioning guilt

They are united in believing in Coe's innocence and their belief that capital punishment should be abolished in Tennessee. It wasn't always that way. Mayberry always believed her brother was innocent. DeShields did not, until about a year ago, when Robert Coe sent her court documents his attorneys filed to support their theory that someone else committed the crime. DeShields is guarded about the documents and the envelope they came in, which has "Happy Birthday" written on it by her brother.

"You're not there, so you don't know what happened," DeShields said. "You always try to weigh out things. You know, did he or didn't he?"

The documents include conflicting witness accounts of Cary Ann's disappearance, conflicting descriptions of the man who took her and the car he took her in, witnesses identifying someone other than Coe as the kidnapper in a police lineup, and bloody clothes, belonging to someone other than Coe, that disappeared before the case was finished. DeShields changed her mind and stood by Coe, believing he did not kill Cary Ann; the courts did not.

Jimmy Coe, who is deaf from a bout with spinal meningitis when he was a year old, also defends his brother. He speaks with those who don't know sign language through his wife Frances, who does. "At first when I heard about it (the killing), I was mad about it and it hurt my feelings. But I visited him in prison and asked him if he did it," Jimmy Coe signed. "Robert looked me in the eye and said, 'I did not do it. I swear to you, brother.' And I believed him. "I know Robert did a lot of crazy things, but he did not kill that little girl."

All of the siblings knew their brother was mentally ill. "We knew Robert had mental problems. We knew that he flashed," DeShields said. "When we were children, the welfare people were called to our house. They would never help us."

Robert Coe later told his siblings that when he was a young boy, an elderly man who lived down the road did something to him that made him flash. He would never tell them what it was. Roger Coe doesn't talk about his brother, and declined to participate in the interview. He nearly left the church Saturday when he learned a reporter was present.

"It's harder for him, you have to understand," Mayberry said. "His last name is Coe. He just says he loved him. He couldn't deal with it the way we have."

Coe had a daughter, who was born about nine months before his arrest for Cary Ann's murder. Rebecca, whose name was changed by the courts in an attempt to protect her identity, wrote to her father from the time she was 14 until last year. About two months ago, she moved away and hasn't been heard from since by Coe's siblings. "Everywhere she moved over the years, everybody would find out who she was," DeShields said. "Everywhere she went, it caused her torment and pain."

Even though they were warned not to come, three of Coe's siblings said they could not have stayed away from the execution. They "had front row seats" when Coe was given the lethal injection shortly after 1 a.m. on April 19. DeShields didn't want her brother to die alone; Mayberry didn't want him to see only strangers in the witness room. Jimmy Coe said he wanted his brother to know he loved him until the end. Frances Coe, Jimmy's wife, came to translate his brother's last words for her husband. Those words ended with "I'm gone."

They spent about six hours with him in the last few days of his life. "The last 45 minutes was the hardest I've ever spent in my life," DeShields said. "He started crying. We talked very slowly." "He asked me, 'Do you think I'm gonna die?' and I said, 'Yeah, I think this is it,' " Mayberry said. "Then we talked about playing as kids." "And he talked about the things that hurt us so bad in our lives, the things that happened to us as kids," DeShields added.

Those things included their father, Willie Coe, hitting the young Robert in the head with a hammer. There was also sexual abuse, which Robert was made to watch. Details about that abuse, reported repeatedly over the years by media agencies, embarrassed the family. "Some of the things our kids didn't even know," Mayberry said. "Those weren't things we were going to tell our kids."

"To have all this stuff revealed about our childhood was like taking a knife and cutting us open from our head to our toes and opening us up for the whole world to see," DeShields said, with tears streaming down her worn face. "Every time we heard about it or read about it, it was like the abuse happened all over again."

The family is now trying to put the entire chapter behind them, although they admit it will never really be over. "I'm going to do everything I can to fight against the death penalty. We want whatever is said and done now to benefit everyone else," DeShields said. "We don't want another state killing." "For years, our life has been a roller coaster, up and down, up and down. I don't even know where to go next," Mayberry said. "It's like I'm in limbo. I don't know."

Jimmy Coe looked bewildered when the question of what happens next in his life was translated to him. "I don't know," he signed. "I'll remember it all my life."

Coe's remains will be placed in a private family location, Mayberry said. "It's time to put it at rest," she added. "Let it go. Let him rest.

"Coe: Crazy or Cunning? Experts are Split," by Lawrence Buser. (The Commercial Appeal)

January 21, 2000 - Opposing mental health expert reports say condemned child killer Robert Glen Coe is either "the boy who cried wolf" and is faking mental illness to avoid execution or "a brain-damaged individual suffering from chronic paranoid schizophrenia." The experts, three psychiatrists and a psychologist, will be the key witnesses in a competency hearing Monday in Criminal Court that Coe is scheduled to attend under tight security. Coe's local defense attorney, Robert Hutton, asked that special security precedures be taken. He said Coe has made numerous suicide attempts over the years and has received death threats from other state inmates. "I have an extreme safety concern for Mr. Coe," Hutton told Judge John Colton Jr. "Given the nature of this case, I think there's a high probability of something happening without extraordinary precautions being taken." The court-ordered reports, filed last week, were made public Thursday after being kept under seal. Coe is to be executed at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville March 23. It would be the state's first execution in 40 years.

Two defense-recommended experts say Coe has a long history of mental illness and will not be mentally competent to be executed. Two prosecution-recommended experts counter that Coe has an equally long history of faking or exaggerating mental illnesses and that he is competent. Coe, 43, was convicted in Memphis in 1981 in the abduction, rape and murder of 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin of Greenfield in northwestern Tennessee. He confessed to the crime and told authorities he stabbed her in the neck after she told him "Jesus loves you." Under the law, an inmate is not mentally competent to be executed "if he lacks the mental capacity to understand the fact of the impending execution and the reason for it." The evaluations, while focusing on Coe's mental condition, also give an inside glimpse of his life behind bars. Prison records cited in the reports paint Coe as a reclusive loner with longtime fears that other inmates want to kill him for murdering a young girl. The reports indicate his fears are not unjustified.

Coe told doctors other inmates call him "baby killer" and that he stays in his cell 24 hours a day for safety, passing time by drinking instant decaf coffee, smoking up to 40 cigarettes a day and watching nature shows on television. The denture-wearing Coe has shaved his head and chest because of a sensitivity to dust mites. In 1989, he cut his throat because he was not receiving his lithium, and a year later cut both forearms with broken glass from a television screen. Although still fighting execution, Coe professes to believe in reincarnation and says he is prepared - and expects - to be executed. "It doesn't matter how you die - you're going to die," one report quotes Coe, who last fall "picked the needle," choosing lethal injection over electrocution. "I'm ready to go to the next life. Get me out of that room (cell) up there. People think you have it made up here. I'd rather be dead than be up here."

He also told doctors he wants his lawyers to prove him innocent rather than crazy, but that he could not remember the name of the girl he was convicted of killing or the alleged motive. "People get murdered all the time," Coe told one doctor. Coe believes himself to be the subject of a government plot, one report said. Last fall, Coe wrote a letter to Cary's mother, Charlotte Stout, professing his innocence, saying he was framed and that "only God can help you or me right now."

Coe has a long history of family and drug abuse, repeated arrests for exposing himself in public and had been committed to mental hospitals here and in Florida on four occasions prior to his murder case. The examiners, who are being paid by the state $300 an hour each plus expenses, included psychiatrist Dr. Daryl Matthews of Honolulu and psychologist Dr. Daniel Martell of Newport Beach, Calif., both recommended by state prosecutors, and psychiatrist Dr. James Merikangas of Woodbridge, Conn., and psychiatrist Dr. William Kenner of Nashville, both recommended by Coe's defense team. Matthews and Martell are with the forensics consulting firm of Park Dietz & Associates, which was involved in evaluations of Milwaukee serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, who was found sane in 1992 and sentenced to life in prison, where he was killed by another inmate.

Among the findings of the four doctors: Merikangas called Coe "a brain-damaged individual suffering from chronic paranoid schizophrenia" who is incompetent to be executed and will be incompetent on March 23; "Mr. Coe does not understand the meaning of death, nor does he feel that being executed will be punishment," he said; "Rather, he views his forthcoming execution as a release from his present situation in order that he may return to life, according to his delusions." Kenner, in the past month, found Coe competent in two visits and not competent in two others, including one on Jan. 11 in which he said Coe was strangely forgetful, suspicious, angry and ordered him to leave; The doctor said that -had in the past likely were due to drug abuse and stress rather than a major mental illness. He said Coe does not have schizophrenia and is not delusional; "In my opinion, Mr. Coe is aware of his impending execution and the reason for it," Matthews said.

Robert Glen Coe gave two confessions to agents of the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation in September 1979 - one taped, one handwritten - admitting to the kidnapping, rape and murder of 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin in Greenfield, Tenn. Here is the graphic handwritten confession. Though it is disturbing, The Commercial Appeal feels it is important that readers see it as Coe moves closer to becoming the first person to be executed in Tennessee in 40 years:

COE'S CONFESSION

"On Saturday September 1, 1979, I worked at the Carroll County Collision Body Shop in McKenzie. While I was at work my boss sent me out for some parts and I took his old truck and went to Paris and tryed (sic) to flash but I did not see anyone to flash so I returned to work.

"I had had the urge to flash all day but could not find anyone to flash at. I drove around in Greenfield trying to find someone to flash at when I pulled into the parking lot of the church and parked and that is when I saw the little girl and boy on the bicycles. They were back to the right from the church. I pulled out and followed them and I lost sight of them so I circled the block and then I saw them again.

"I pulled up and stopped beside them and talked to the little girl. I ask her where her daddy was and she said at home. I ask her to show me where he lived. She said that she had to leave her bicycle somewhere so I told her to go back down to the church. I don't think I said anything to the little boy at that time.

"I told her I had not seen her daddy for awhile and that is when I ask her to show me where he lived. They followed me back to the church. When I got to the church I stopped and she got into my car a 1972 Ford Torino four-(4) door brown over greyish brown. She got into the front seat. She told the little boy to watch the bicycles. When she got into the car I drove down the street and turned left. "She ask me where I was going and I told her for a ride. She just hung her head down and she did not say anything else.

"I drove around some streets and I drove up a gravel road to a ball park and turned around because some cars were parked there. I drove around on some more roads looking for a place to go and I finally found that gravel road. I did not know that road was there. I just found it. I also drove down some more roads looking for a place to stop. When I got to the gravel road I just pulled down the road and turned around and stopped. "The little girl did not say anything. (Coe then describes in graphic detail how he raped Cary.)

"I told her to shut up as I finish my sex act. She told me that Jesus loves me and that is when I got so upset and I decided to kill her. When I finished the sex act I pulled up my pants and I got out of the car and I walked around the car and I opened the door on her side of the car and I caught her around the neck and and jerked her out of the car and I tryed to choke her to death with my hands. She turned blue in the face, but she woud not die so I choked her and made her walk down the road into the weeds away from the car. She walked backward down the lane and I pushed her and choked her. "I stopped and I told her to shut her eyes and I took out my pocket knife and opened the blade and I caught her by the hair on her head and I pulled her head back and I stabbed her in the neck once and pushed her down on the ground.

"After she fell to the ground she ask me if I was going to kill her. She started jerking and grabbing at her shirt at the neck. I stood there and watched the blood come out of her neck like turning on a water hose. She struggled and jerked. I don't remember her shoes but I may have placed them by her body I don't know. I got some blood on my hands and I pulled some leaves off the bushes and wiped the blood on them. I then ran and tryed to get away from there.

"I pulled out of the gravel road onto the paved road and turned right as I was driving I hit some bumps in the road and I still had the knife in my hand and the blade stuck into my finger when I pulled off the paved road onto Highway #45 and turned right in the direction of Martin. I pulled out into the path of a big truck and he swerved ... around me. "After he passed I threw out the knife into a bean field. I went to Martin and then onto Dresden to my sister-in-law Vicki Box's but my wife was not there and then I started back to McKenzie to find my wife. As I was driving by the nursing home in Dresden I threw my flip flops out of the car window because of foot prints I left at the scene where I killed the little girl. I went on to McKenzie and got me another pair of shoes. I came back to Dresden where my wife was at her sisters. "I also changed the color of my hair from light brown to dark black. I did this Monday night. I also traded my 1972 Ford Torino for a 1972 Mustang at Crestview Motor in Gleason. I did this because of the description of the car and me on the news. I told my stepfather about stabbing someone and he laughed at me. I told Darrell Rose and my wife that I had stabbed a state trooper at Camden and that that was why I had to change the color of my hair and get out of town. They took me to the bus station in Huntingdon and I was going to travel under the name of James Watson. I was going to Georgia.

"Some of the towns that I have flashed in before are Tiptonville, South Fulton, Martin, Paris, Union City, Greenfield, Sharon, Gleason, Dresden, McKenzie, Henry, Lexington, Obion, Troy, Jackson and Samburg. The above statement is true and correct. I am giving this statement of my own free will.

"(Signed) Robert Glen Coe 9-7-79"

TIMELINE

1979

Sept. 1 - Cary Ann Medlin is abducted a few blocks from her Greenfield, Tenn., home. Her body is found in a field the next day.

Sept. 4 - Police arrest Robert Glen Coe in Huntingdon, Tenn., as he prepares to board a bus to Georgia.

1981

May - Coe sentenced to death for first-degree murder and given life sentences for aggravated rape and aggravated kidnapping.

1983

The Tennessee Supreme Court affirms the judgment.

1984

- The U.S. Supreme Court refuses to review the case.

- Coe files for post-conviction relief, saying his attorneys did not present an adequate defense.

1986

The trial court denies Coe's petition. The state Court of Criminal Appeals upholds that decision.

1987

Coe files for a writ of habeas corpus in federal court.

1989

The request is denied two years later for failure to exhaust state remedies. Coe files a second state post-conviction petition, which is denied six months later, affirmed on appeal and denied review by state Supreme Court.

1992

Coe files second federal petition for writ of habeas corpus, citing constitutional errors in his trial.

1996

U.S. Dist. Court Judge John Nixon dismisses Coe's conviction and death sentence, citing improper jury instructions and cumulative errors throughout the trial.

1998

After reviewing an appeal by Tennessee, three-judge panel of the Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati reverses Nixon and on Nov. 16 reinstates Coe's conviction and death sentence.

1999

March 15 - Sixth Circuit refuses Coe's petition to have his case reviewed by the full panel of judges, which normally includes about 15 members. Also in March, the Tennessee Supreme Court denies Coe's third post-conviction petition, which had been filed in 1995 and denied by the lower courts.

Oct. 4 - The U.S. Supreme Court gives the go-ahead for Coe to be executed on Oct. 19.

Oct. 11 - Tennessee Supreme Court delays Coe's execution to allow his appeal for reconsideration to the U.S. Supreme Court by Oct. 29.

Nov. 19 - Coe's attorneys ask U.S. District Judge John Nixon to reopen the case and block his execution.

One of the death sentences that U.S. District Judge John T. Nixon reversed, prompting calls for his impeachment, was reinstated by a federal appeals court. A three-judge panel of the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled 3-0 that Nixon wrongly reversed the conviction that Robert Glen Coe received for raping and murdering an 8-year-old girl in rural West Tennessee in 1979. The appeals court reinstated both the conviction and the death sentence that a Shelby County jury gave Coe in 1981 for the torture-murder of Cary Ann Medlin.

In February 1981, Coe was convicted of the Labor Day 1979 kidnapping, rape and murder of 8-year-old Cary Ann. U.S. District Judge John Nixon in 1996 threw out Coe's convictions for 1st-degree murder, aggravated rape and aggravated kidnapping. Nixon's ruling -- which angered supporters of the death penalty -- wiped out Coe's death sentence for the murder conviction and his two life sentences for the rape and kidnapping convictions. Coe told police in 1979 that he kidnapped the girl, sexually assaulted her and cut her throat. He also said that just before he killed her, she said to him, "Jesus loves you, Jesus loves you." He tried unsuccessfully to withdraw the confession and was convicted. Tennessee appeals courts upheld Coe's conviction. But Nixon threw it out, saying the trial jury was given improper instructions on when capital punishment should be applied, including on the issue of whether the killing was done with malice.

Medlin's mother, Charlotte Stout of Greenfield, Tenn. said she was "really relieved" by the appeals court action, since Nixon's December 1996 ruling would have given Coe a new trial. "I couldn't imagine going through that again," Charlotte said. Coe admitted, three days after Cary Medlin disappeared in September 1979, that he lured her into his car as she rode a bicycle near her parents' home in Greenfield, Tenn. Coe, who had a history of mental illness, told authorities that he sexually molested the girl, then tried to choke her and, when that did not work, stabbed her and watched her bleed to death.

Nixon reversed Coe's conviction and death sentence in December 1996 because of what he called errors the trial judge made in instructing the jury. Nixon said the judge at Coe's trial did not give the jury enough guidance when he defined the terms "heinous, atrocious and cruel," "reasonable doubt" and "malice." The 6th Circuit panel disagreed with Nixon on each of those points. Nixon has reversed five death sentences imposed by Tennessee juries, and higher federal courts have affirmed his rulings in four of those cases. But his reversal of Coe's conviction and death sentence stirred a grass-roots campaign, based in Greenfield, calling for his impeachment. Nixon has a well-known anti-death penalty stance and has accepted awards for such. Both houses of the Tennessee legislature jumped on the impeach-Nixon bandwagon, and Charlotte Stout went to Washington to testify before a congressional committee. But Congress took no action against the judge. Nixon, 65, has now "taken senior status," or semi-retirement, as a trial judge.

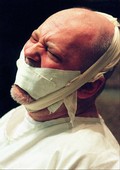

"Preparation for Execution; State Video Records Coe Minutes Before Execution," by John Shiffman.

Small segments of a silent and stark 22-minute video that show Robert Glen Coe's transfer from his cell to the execution chamber April 19 may be released today by the state. The heavily censored videotape, obtained by The Tennessean via court order, offers a rare glimpse of the prelude to an American execution, and the tapes' probable release triggered debate over whether the state should have recorded it, and whether the media should publish it. "I don't know whether it should be made public or not, honestly," said Robert Hutton, the defense attorney who was with Coe during the time the video was shot. "On the one hand, out of respect for Robert -- he's been dragged through the mud enough -- I'm not sure it needs to be shown. On the other hand, I think it's important for people to see how barbaric this whole process is." (link contains video and transcript)

Advocates of the death penalty have said publicity of events surrounding executions may be a deterrent to serious crime. But one of them, victims rights advocate Rebecca Easley, said she worried the images would "elicit sympathy for Coe." The video was recorded by prison guards just before 1 a.m. on April 19, in the tense minutes before Coe became the first person executed in Tennessee in 40 years. Coe was sentenced to death in 1981 for the rape and murder of 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin.

"I don't mind the dying part," Coe says moments before he is executed, according to a transcript of the video compiled by the state Department of Correction. Correction spokesman Steve Hayes said prison officials made the tapes "to document the cell extraction" and "to make sure things were done correctly." The state spent about $2,000 to record it, records show. Hayes said the state "possibly" will record the preludes to future executions. The next death-row inmate in line is Philip Workman, who is scheduled for execution Jan. 31. State law prohibits the recording of actual executions, and Hayes has said the state did not record Coe's execution. Because the tapes are so heavily censored -- about 19 of the 22 minutes are essentially blacked-out -- it was unclear yesterday when it begins and ends. The state said a Tennessee law that shields the identities of execution participants prevented officials from releasing a less-censored version of the tapes. The first part of the tape shows a one-second shot of Coe being wheeled from his cell to the execution chamber. A fuzzy image then follows of Coe's head in position for execution. Later, Coe is seen bouncing from one foot to another in his cell. Fearing voices might be identified, the state deleted sound from the censored tapes and provided a limited transcript. At one point, Coe says, "I want to make it easy, you know."

Then he asks about the chemicals that will put him to death: "The stuff just comes in you, does it just go to sleep?" And the answer: "The first one puts you to sleep, the second one will stop the breathing, the third one stop the heart, OK." A spokeswoman for the state attorney general said earlier this month the office would not comment on the tapes.

In an e-mail, Coe's sisters asked The Tennessean not to pursue release of the tapes, arguing their family had suffered enough.

Federal Public Defender Henry Martin, who was Coe's chief lawyer from 1987 until his death, said he felt sorry for the family but would not quarrel with the newspaper's decision to publish the images. He said he found the state's effort to record the moments before the execution disturbing.

"It just smacks too much of the Third Reich, as if they're treating people as experimental beings so that we learn how to more efficiently kill somebody. I can't see that as being consistent with a humane, caring society," Martin said.

Vanderbilt University sociology professor Gary Jensen said that while some believe public executions will deter crime, and others believe the opposite, studies have shown that publishing such images will probably have no "net effect on public opinion or the death penalty."

A decision to publish or air part of the video is a "tough call" for the media, said Middle Tennessee State University journalism professor Richard Campbell.

"I would weigh the greater public good of what the citizens and your readers are going to get from this against the objections of the family. Certainly, this is state action, but it's also the revealing of a very painful and tragic and private moment."

Al Tompkins, a former Nashville TV news director who now teaches at the Florida journalism think-tank The Poynter Institute, said he is "hard-pressed" to see The Tennessean's justification for printing the image on the front page.

"Simply because the newspaper fought for it in court is not a defensible argument for using this picture. Publishing one photograph, or using a videotape, is not and should not be a replacement for serious coverage of issues."

National execution expert Michael Radelet, who leads the sociology department at the University of Florida, said he knows of no news outlet that has ever published a video that shows what happens before an execution.

Recently, the Florida courts posted graphic photographs of a botched execution on a Web site. The picture was an exhibit in a court case.

Richard Dieter, of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, D.C., said while he opposes the live broadcast of executions, a videotape of the moments before might add to the public debate. "I think knowledge is a good thing. On the whole, it's an area where there's been a lot of myths and, when everything is done after midnight and the only thing you hear is the last words and the last meal -- as if that's all you needed to know -- there is more to this. It's all part of the debate," Dieter said. The Tennessean learned of the tapes in late July, while reporting a series on the execution, and requested them under state public record laws. The Correction Department refused, and the newspaper sued, asking a judge to force the state to alter the tapes to hide the identities of the participants in the execution. Though the case remains unresolved, the Correction Department has provided the newspaper with a heavily censored version, which it will release to other media today.

"Scenes From an Execution," by John Shiffman. (Special 8 part series by the Tennessean that includes articles, video, and images from the Coe case)For years, they kept silent. Lawyers and other officials who wanted to execute Robert Glen Coe and those who wanted to save him felt they could not talk publicly. Now, these insiders are breaking that silence.

They are talking in detail for the first time about what went on behind the scenes the day the state carried out its first execution in 40 years. What they say may surprise many Tennesseans. A sampling:

- Not every state lawyer arguing for Coe's execution was a fan of the death penalty. At least two senior government lawyers had misgivings.

- Defense lawyers didn't coach Robert Glen Coe to act crazy in the final days in a desperate attempt to halt the execution. The opposite was true.

- Charlotte Stout, the mother of victim Cary Ann Medlin, convinced prison officials to convert a special room so she could witness the execution live, rather than on video monitor.

In an eight-part series that begins today, The Tennessean recounts that final day, taking readers into the minds of the lawyers, judges, families and other participants on both sides of the case. Their thoughts, their prayers, their nightmares, their strategies. These people confronted issues and conflicts that mirror the concerns of many Tennesseans about justice and capital punishment. Their stories are significant because most of the players will repeat their roles in future executions.

"Coe Scheduled to Die Early Wednesday," from Sun and wire reports. (April 18, 2000)

NASHVILLE - As Robert Glen Coe was moved to the death watch area of Riverbend Maximum Security Institution Monday, a federal appeals court refused to stay his execution, leaving the fate of the convicted child murderer and rapist in the hands of the U.S. Supreme Court. Coe, 44, is scheduled to die by lethal injection Wednesday at 1 a.m. CST for the 1979 kidnapping, rape and murder of 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin of Greenfield.

Coe had asked the full 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati to review a decision made by a three-judge panel of that court that found Coe mentally competent for execution. In denying the full hearing, the 6th Circuit said Coe's concerns were fully considered by the three-judge panel and did not deserve another hearing. Coe's attorneys have also asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review Coe's mental competence and Tennessee's method for determining it.

U.S. Supreme Court standards prevent the execution of the insane. The threshold question is whether the inmate understands the punishment and why he or she is receiving it. After a four-day trial court hearing in Memphis in January, Judge John Colton ruled that Coe meets the standards required for execution. Coe, once a part-time auto mechanic, is set to become the first person executed in Tennessee in 40 years.

He cursed and spat at prosecutors during the trial, causing Colton to have Coe gagged and then removed from the courtroom to watch the proceedings from another room by television. Coe was calm after he was removed from the courtroom. The trial court's decision has been upheld by the Tennessee Supreme Court and two tiers of federal appeals courts.

The Jackson Sun

In the last month, Coe has twice come within 16 hours of being executed. Both times his execution was stayed by federal courts while they reviewed the competency question. Mickey Stout, Cary Ann's stepfather, said he has a "gut feeling" the execution will be carried out this time. "I've been wrong every time," Stout said from his home in Greenfield Monday. "But I don't think the Supreme Court will touch it." He added that in all of Coe's previous appeals to the Supreme Court, the high court has refused to hear it. "I think it's going to happen this time," he said. Stout and his wife, Cary Ann's mother, Charlotte, plan to hold a 5:30 p.m. memorial service for the girl at Centennial Park in Nashville.

Anti-death penalty advocates and religious groups are also planning activities in Nashville today. At Belmont Methodist Church, in Nashville's Hillsboro Village, the Tennessee Coalition to Abolish State Killing will hold a service to pray for both Medlin and Coe. The coalition is also hosting speakers and music - including singer-songwriter Steve Earle - at the prison at 10 p.m. This will be followed by a silent vigil starting near midnight. "I don't think this execution will do justice appropriately," said Sky McCracken, pastor of East Trinity United Methodist Church in Jackson. He is against the death penalty and plans on attending the service and the vigil tonight. "You don't solve one murder with another, whether it's state-sanctioned or otherwise." Some state religious leaders have condemned the Tennessee Supreme Court for scheduling the execution during the holiest week on the Christian calendar and at the beginning of the Jewish Passover. Wednesday is the first evening of Passover and four days before Easter. A spokeswoman for the state's high court said the justices chose a date one week from April 11, when a federal court lifted Coe's stay of execution.

But religious leaders say the timing shows insensitivity and even indifference to the state's people, culture and beliefs in the heart of the Bible Belt. "The truth is there's just no good day, no good week and no good year to do this," said Harmon Wray, a death penalty opponent from Nashville who works on criminal justice issues for the United Methodist denomination.

Schedule for Coe's last day

Robert Glen Coe, 44, has spent the last 21 years of his life in prison, sentenced to die one day for the rape and murder of 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin. Today he is spending his last day in custody in an 80-square-foot death watch cell, 50 feet from the cross-shaped lethal injection table where he is scheduled to die at 1 a.m. Wednesday. Here's how Coe will spend his last day, according to Ricky Bell, the warden at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution, located in West Nashville. Robert Glen Coe was expected to be awakened at about 6 a.m. today for his last day. In Building 8, where his death watch cell is located, he will be allowed to receive visits from previously approved family members and friends, as well as his attorneys. He also has access to a minister.

Two days before his March 23 execution date, Coe requested his last meal to be catfish, french fries, cole slaw, white beans, pecan pie and sweet tea. He is scheduled to be served that meal between 4:30 and 5 p.m. At midnight, Coe will dress in cotton trousers, shirt, and socks or cloth house shoes. At 12:55 a.m., he will be asked to step to the door of his cell and be handcuffed. If he refuses to leave his cell, the "extraction team" will remove him. He will then be strapped to the gurney and wheeled into the death chamber. Inside the death chamber, the gurney will be bolted to the floor. The IV technicians will insert a catheter into each arm, attach the tubing and start an IV. At 1 a.m., Coe will be allowed to make a last statement, and the lethal chemicals will be released into the IV lines until Coe is presumed dead. His request to Gov. Don Sundquist for clemency already has been denied.

Tennessee: New Impending Execution Date Set

The Tennessee Supreme Court set a new execution date yesterday for convicted child-killer Robert Glen Coe -- Wednesday, April 19 -- after a federal appeals court panel said Tennessee courts gave Coe a fair hearing on whether he is mentally competent to be executed. Coe's lawyers are expected to ask the full 6th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, and then the U.S. Supreme Court if necessary, for another stay of execution while they pursue their claim that Coe is too mentally ill to be put to death by the state. But further delays become less likely as Coe's case goes higher in the federal court system, said Nashville lawyer and legal scholar David Raybin.

"There is a remote possibility that this could be postponed one more time, for a week or so," Raybin said yesterday. "But I would expect Mr. Coe to be executed by the end of the month. This is a train that is just not going to stop." Coe has received 2 stays of execution from federal courts within the past 3 weeks -- each of them less than 24 hours before he was scheduled to die by lethal injection at Riverbend prison. But yesterday's appeals court ruling on Coe's mental condition removed one of the last obstacles to his becoming the 1st prisoner executed in Tennessee since 1960. Gov. Don Sundquist has said he won't do anything to reduce Coe's death sentence, which he received for kidnapping, raping and murdering an 8-year-old West Tennessee girl, Cary Ann Medlin, in 1979.

A Memphis trial judge ruled Feb. 2, and the Tennessee Supreme Court agreed on March 6, that Coe is mentally competent to be executed, despite a history of mental problems both before and after he was convicted of murdering the little girl.

Congressman Ed Bryant - Press Release

STATEMENT BY CONGRESSMAN ED BRYANT CONCERNING TENNESSEE'S EXECUTION OF ROBERT GLEN COE.Washington, D.C. - Tennessee has carried out its ultimate criminal penalty for the first time in four decades with the execution of Robert Glen Coe earlier this morning. Our justice system has overcome an unconscionable number of years of appeals which all too frequently brought this case to a frustrating standstill. Certainly Mr. Coe was deserving of his punishment, as his unspeakable crimes robbed a young girl and her family of her innocence and life. As Tennessee now has carried out the mandate of an impartial jury and the will of its citizens, we should be mindful of the gravity of this sobering moment in our state's history.

For a strong majority of Tennesseans, the moral imperatives of justice require that the death penalty be carried out. I have always supported appropriate use of the death penalty since it serves as a deterrent to violent crime and because it provides a degree of closure to the victim's family. But while I support the death penalty, I find no happiness in the death of any fellow human being. Indeed, the taking of a life is the most powerful right conferred upon the states by our Constitution. It should be exercised with the utmost care, and in this case, I am comfortable that it was. Mr. Coe filed numerous appeals in state and federal courts for some twenty years and without any doubt "had his day in court".

I can only hope that the families of his victim, as much as possible, will be able to finally put this terrible murder behind them and move forward with their lives. Justice has been served

Fight the Death Penalty in the USA

Robert Glen Coe, 44, 2000-04-19, Tennessee

Convicted child-killer Robert Glen Coe was executed this morning at Riverbend prison. He is the 1st person put to death in Tennessee since 1960. Coe, 44, was put to death by lethal injection.

He was executed for the 1979 rape and murder of Cary Ann Medlin, age 8, in Greenfield, Tenn. Coe was put to death at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution, a facility in Nashville's Cockrill Bend industrial area that houses the state's death row.

Family members of both Coe and Medlin were present for the execution. Included in the group of about a dozen of Medlin's family were Cary Ann's mother, Charlotte Stout, who spoke yesterday afternoon at a memorial service for her daughter in Nashville's Centennial Park. Medlin's father did not witness the execution because he could not arrive in time from Florida. He had come to Nashville last month when another of Coe's execution dates was canceled when an appeals court postponed it. Medlin's stepfather, James Michael Stout, was at the prison among the family last night.

Members of the Coe family were also present. Both family groups witnessed the execution, but the Coe family will watched via closed-circuit television and the two family groups remained separated. Outside the prison walls but inside its towering fences, a group of anti-death penalty protesters held a candlelight vigil and sang gospel songs.

Near the prison's administrative building, a brown wooden podium was set up bearing the state seal and holding a microphone. Near it were 8 brown folding metal chairs that will apparently seat the media representatives who have been picked by the state to witness the execution. After the execution, those witnesses will give interviews about what they have seen.

(sources: The Tennessean & Rick Halperin)

Cary Ann Medlin Memorial Home Page

According to her murderer's confession, Cary Ann Medlin's last words to him were: "JESUS LOVES YOU."

Cary Ann was an average 8 year old little girl. Brown hair framed her sweet face, and big brown eyes enhanced her constant, glowing smile. This darling won the hearts of any who crossed her path with her soft-spoken ways and zest for life. Cary attended Sunday School at the First Baptist Church in Greenfield, Tennessee. She learned at an early age about the love of her Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

Her favorite color was pink. She loved country music, and often pranced around the house singing, "Turn Your Radio On". She loved to swim and ride her bike. She took ballet and wore her pink tutu in her first recital. Her favorite cartoon was "The Pink Panther" and she had a huge stuffed Pink Panther on her bed. She loved being barefooted and hated shoes! She sucked her thumb until she was almost 2 years old. She was a carefree little girl that loved life, and lived it with passion. She couldn't understand why people sometimes lied. Cary loved everyone she ever met and lent a hand anywhere she could...even to a total stranger....

On September 1, 1979, Cary and her step-brother were riding bikes in the neighborhood. A friendly man in an old car pulled up beside her. He seemed to know her father and he persuaded Cary to show him where she lived. She parked her bike in front of a nearby church and climbed into the car. That was the last time Cary was seen alive. As soon as Cary was reported missing, the entire community went into action. Scores of volunteers combed the nearby areas searching for her and the suspect vehicle. The next day, the family's worst fears were confirmed when Cary's body was found at the end of a field road on the outskirts of town. Soon after, a family member of Robert Glen Coe reported suspicions of him to the police. He was consequently arrested and charged with the kidnapping, rape and murder of Cary Ann. Most of the confession was a nightmare for the family. There was, however, one part of the Coe's testimony that stood out. It was that something that told Cary's loved ones that the Lord had taken care of her, even to the end. Just prior to ending the misery of this poor defenseless angel, Coe said she looked up at him with trusting eyes and said, "Jesus loves you." Even Coe choked back tears telling this part of his confession.

Coe was brought to trial and found guilty in 1981. He was sentenced to two life sentences for the kidnapping and rape. He was given the death penalty for murder. For 21 years this case languished through the judicial system. To the family's horror it landed on the desk of Judge John Nixon in the Middle District of the Federal Courts in Tennessee. Judge Nixon had a reputation of overturning death sentences. He did not disappoint. Cary's mom, Charlotte Stout, went to Washington, D.C. and testified about Judge Nixon's actions to the Subcommittee for Courts and Intellectual Properties (a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee) in 1997. (see link) Judge Nixon was not impeached, however he semi-retired in 1997. He still receives his full salary and still hears a 60% case load. To our knowledge, he has not received another capital punishment case. After 21 years of trial and appeals, Robert Glen Coe was executed on April 19, 2000. It was the first execution in the State of Tennessee in 40 years and the first lethal injection, ever. Cary's family watched the execution from an adjoining room. Much to their sadness, Coe did not apologize before his death. Finally, 6 months before what would have been her 30th birthday, Cary rested in peace.

The "Cary Ann Medlin Memorial Scholarship" is given annually to a graduating senior at Greenfield High School in Greenfield, Tennesseee. This is a completely self-limited scholarship (must be replenished every year) and depends totally on donations from family and friends. It is awarded to a student based on financial need and merit. If you would like to contribute to this scholarship or if you have questions, please click on the link and email Cary's family. We do not accept the donations personally, but will route you to the contact person at our local university.

Coe Execution; Execution Politics; Execution Trends; Religious Debate; Execution Witnesses; Inmates on Death Row.

Family says goodbye to Robert Coe; Coe the day after; Execution is carried out after last-minute court action; Mother remembers Cary Ann; Crowd prays over execution; Witnesses to the execution; Greenfield deals with publicity; Three more area men await execution dates; An in depth at the future of executions in Tennessee and religious questions surrounding the death penalty. Click here.

The Coe Index - Legal Proceedings; Schedule for Coe's last day; Whom to Know; Timeline September 1, 1979 to present; Search for Cary Ann; Robbed of her innocence; Tracking the killer; '... Nobody can hurt her anymore'; Portrait of a Killer; 'Death Watch'; Cary Ann's family; 'Death Watch' Coe; Lethal Injection; Letter from Charlotte Stout to Coe (10/7/99); Coe's reply (10/13/99); Editorial: What is your opinion of the death penalty?

The photograph of [Robert] at age seven (left), smiling in what appears to be a class photo from Gleason Elementary School. It's believed [that] Coe’s maturity hadn’t grown much since that photograph was taken. He was believed to be the most hated person in Tennessee. The press didn’t help much, always referring to him as “convicted child-killer" Robert Glen Coe. As if child-killer was part of his name. Robert was nothing more than a misguided boy in a man’s body. The public didn’t appear to know much about Coe’s mental history, his wrenching childhood or evidence that could cast doubt on his guilt.

Most Tennesseans have never even heard of Donald Gant, the Greenfield man, reported as the number-one suspect by criminal investigators in 1979, questioned shortly after the crime and identified in a lineup by three eyewitnesses, Cary Ann’s brother and grandmother and a man who had known Gant for years—also identified Gant as the person he saw in the car with Cary Ann. Most didn’t know that police found scratches on Gant’s neck—and bloody sheets and clothing in his home—what one might expect following the rape and stabbing of a young girl. That Gant had a history of making inappropriate advances to young girls. Gant kept changing his alibi about what he did the night of the crime. Gant’s car matches the car used in the abduction. Tire tracks at the muddy scene where the body was found, are consistent with tires on Gant’s car. In contrast to this evidence implicating Gant, there was no evidence in Robert Coe’s car of any sexual assault.

Authorities said Gant’s alibi was questionable and since no murder weapon was found, he was released. Robert’s jury hadn’t heard about any of this evidence including the bloody sheets and clothing—evidence now unavailable. Evidence—critical to proving Gant’s guilt—was either lost or destroyed by state agents sometime after Robert’s confession. Data collected through a triangulation of public documentation in the life of Robert Glen Coe presents an in-depth explanation of the truth in his case. Thousands of pages of data for this sociobiography has been collected from: news media, newspaper articles, letters to the editor, editorials, and online discussion forums from sources such as the Dresden Enterprise, Jackson Sun, Memphis Commercial Appeal, Nashville Banner, Tennessean, and the Union City Daily Messenger; court transcripts, legal papers and documents; Tennessee statues and case law; United States code and case law; and United States Constitutional law. Coe case data covers the twenty-one-year period of just prior the Medlin abduction through October 2000.

To be continued:

"Killing Time: Tennessee prepares for its first executions in four decades," by Jeff Woods. (September 23, 1999)

The heavy metal door swings open, and Philip Ray Workman steps out of the shadows into the glare of the fluorescent lights in the visiting room on death row. Muscular like many convicts, he looks fit and wears wire-rim spectacles and a neatly trimmed goatee. In another context, he could pass for a health spa masseuse. He smiles as he shakes my hand, and appropriately enough for someone who may have only a few more months to live, he goes straight to the point. “I really appreciate your coming,” he says. “I need all the help I can get, Lord knows.”

Workman, a born-again Christian who claims he’s an innocent man, could become the first person executed in Tennessee since 1960—that is, unless luck runs out faster for Robert Glen Coe, another convicted killer who says he didn’t do it.

After nearly four decades without an execution in this state, there now are two condemned men down to their final legal appeals, and three more nearing the last of theirs. It seems likely that soon, possibly by year’s end in the cases of Workman and Coe, Tennessee finally will begin satisfying the overwhelming public clamor for the deaths of murderers. Death-penalty proponents contend executions will mete out justice and retribution, even if they don’t make Tennessee a safer place. Opponents argue capital punishment will cheapen everyone’s life and descend the state into a kind of barbarism in which some people die because they had bad lawyers.

The final appeals of Workman and Coe contain all the makings of a John Grisham bestseller: There are shadowy characters, official cover-ups, perjury, drugs, insanity, mysteriously disappearing police files, two wrongly accused men, of course, and loads of corrupt cops, bumbling defense attorneys, and arrogant, God-fearing prosecutors.

It’s easy to dismiss it all as the desperate, 11th-hour pleading of condemned men, which is exactly what it is, certainly. The problem is, what if it’s true? Should we be so confident in sending these men to their deaths? These questions aren’t so easily answered. That the state might execute an innocent man isn’t as preposterous as it seems. Since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976, 566 people have been executed. But 82 inmates awaiting executions have been exonerated—six this year. That’s an alarming ratio of one inmate freed for every seven put to death. Regardless of Workman’s or Coe’s guilt or innocence, it’s hard to argue with either man’s contention that he wouldn’t be waiting to die if his first lawyer had mounted the vigorous defense now pressed in his appeal.

Workman and Coe are typical of convicted killers sentenced to die in this country. They are poor, and their victims were white. Workman, 46, was convicted of killing a policeman while robbing a Wendy’s restaurant in 1981 in Memphis. A junkie, he held up the Wendy’s for drug money. Unbeknownst to him, one of the fast-food workers pushed a silent alarm, and when Workman tried to get away, the police were waiting. Gunfire blazed, and police Lt. Ronald Oliver died of a single bullet wound to the chest—of this much, we can be certain, but not a lot else.

Workman at first agreed with prosecutors that he must have fired the bullet that killed Oliver. He now contends another policeman did it by mistake in the confusion at closing time in the restaurant’s dark parking lot.

Coe, 43, was found guilty of abducting and murdering 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin in 1979 in the West Tennessee town of Greenfield. It’s one of the most notorious cases in the annals of Tennessee crime. Coe confessed, saying he decided to kill the girl because, after he raped and sodomized her, she told him, “Jesus loves you.” He said that infuriated him, so he strangled Cary Ann and then, when she wouldn’t die, he stabbed her in the neck with his pocketknife and watched her bleed to death.

A diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic, Coe now claims he was duped into confessing. He blames another man, who was under police suspicion at one time, for the murder.

Cary Ann’s mother, Charlotte Medlin Stout—who has waited 20 years for her daughter’s killer to receive his sentence—already has notified prison officials that she wishes to witness Coe’s execution. “It’s going to be such a great relief that I can’t express it in words,” she told me. “I will be thankful to God in heaven when this is over. Coe has never expressed remorse to me. He has never indicated in any way that he is sorry. So if in those last few moments of his life, he wants to look at me and say he’s sorry, I’m going to be there. “It would help me to know that he regrets and mourns what he did to my child. In those last few moments when it dawns on Coe, ‘Yes, I do have to pay for this,’ that he has to pay with his life, he can look at me and see what my daughter showed him. He can see my forgiveness, and he can ask me for his.”

The U.S. Supreme Court will decide whether to consider the inmates’ cases after the justices convene for their new session on the first Monday in October. If the high court refuses to hear their appeals, as expected, only Gov. Don Sundquist could spare their lives. A champion of the death penalty, Sundquist is very unlikely to grant clemency to either.

Coe could go to his death on Oct. 19, the date set by the state Supreme Court. Workman hasn’t gotten an execution date yet, but the state attorney general says he will seek one immediately if the U.S. Supreme Court refuses to hear Workman’s final appeal.

If the governor won’t intervene, Coe and Workman then must choose the method of their executions: lethal injection or electrocution in the state’s oak-paneled electric chair. Legislators passed a law last year to offer lethal injection as a choice—not in a merciful attempt to lessen the pain of the prisoners, but because of fears that courts might someday strike down electrocutions as cruel and unusual punishment, thus further delaying executions in this state.

On death row, at the state’s Riverbend Maximum Security Institution, Workman winces when I ask how he would choose to die. “I was a drug addict strung out on cocaine when I robbed that Wendy’s. So I’ve thought that since a needle got me here, a needle will take me out,” he says. “But I just don’t know if I could make that choice. It’s kind of morbid.”

He nods across the visitors’ room at his taxpayer-funded lawyer, Chris Minton. “I might tell Chris to choose for me,” he says. “Thanks,” Minton replies in a moment of black humor. “Which way?” Workman continues. “The bottom line is, there’s no good way to go. Dead is dead. I guess to most people, lethal injection seems more humane, but let me show you something.”

He fishes around in the notebook on his lap and pulls out a newspaper picture. It shows the bed used for lethal injections. It’s customized for the job. If Workman is executed in this manner, he will be strapped to the bed with his arms outstretched to receive the poison into his veins. “What’s this look like if you turn it up like this?” Workman asks, holding the picture at an angle over his head. “A crucifix, that’s what. This is nothing more than a modern form of crucifixion. That’s all it is. They’re just using needles now instead of nails.”

Workman and his lawyer are trying to manipulate the media to create public pressure for clemency. Workman won’t grant interviews unless Minton approves, and Minton is choosy. He let Tim Chavez, the liberal columnist for The Tennessean, talk to Workman. In his column, predictably, Chavez asked readers “to stand up for justice” and write the governor to demand that he commute Workman’s death sentence to life in prison. But if Minton suspects a writer is unsympathetic, there’s no interview. Workman wouldn’t see a Memphis Commercial Appeal reporter, for instance.

On the other hand, Coe is refusing all media interview requests. His attorneys, federal public defenders, won’t even return reporters’ phone calls. The less news coverage their client receives, the better, they doubtless reason.

Even a columnist crusading against the death penalty might blanch at embracing Coe’s cause. On death row, Coe has been disciplined for masturbating in front of other inmates, and over the years, he has consistently been portrayed as a monster in the media, which isn’t surprising given the nature of the crime for which he is sentenced to die.

Cary Ann Medlin was murdered on Labor Day weekend 20 years ago. She lived in Greenfield with her mother; her stepfather, Mickey Stout; and her 8-year-old step-brother, Michael Stout. On the day of her abduction, Cary Ann and Michael went riding their bicycles in their neighborhood.

Looking for candy, they paid a visit to Michael’s grandmother, Margaret Stout, who lived on the street directly behind the children’s house. A little while later, Margaret Stout looked out the window while talking on the telephone and saw the children standing by their bicycles and talking to a man in a two-toned brown car.

Cary Ann disappeared around 5:30 p.m. After an intensive search by virtually the whole town, her body was discovered at 2:30 p.m. the next day, 2 miles from Greenfield in the weeds beside a gravel road. Two days later, Coe was arrested at a nearby town’s bus station holding a ticket for Marietta, Ga., and traveling under an assumed name, his dirty blond hair dyed black. When Coe was brought to the Weakley County Jail, a hostile crowd was there, screaming at him and yelling threats. Inside the jail, according to testimony at his trial, Coe asked to speak to one of the law officers, and when they were alone, he said, “I did it.” “You did what, Robert?” the officer asked Coe. “I am the one that killed that little girl,” he responded.

He signed a Miranda form, affirming he understood his rights, then gave his confession. He said he lured Cary Ann into his car by asking her to take him to her daddy. He said he drove to a deserted place. He said that when he stabbed her, the blood came out of her “like a water hose,” and he watched her “struggle and jerk” for a while before leaving her beside the road in a dense thicket and driving away.

The next morning, under public pressure to solve the crime, the district attorney held a press conference announcing Coe was to be charged with murder.

That same day, Coe took two officers on the route he said he followed after abducting Cary Ann. On the way, he pointed out a house and told the officers there was an old man sitting on the porch who saw him go by in his car with Cary Ann. The witness, Herbert Clements, later testified he did see the car and didn’t recognize the driver, but did recognize the girl as Cary Ann.

There was yet more incriminating evidence. When a nervous Coe came home on the evening of Cary Ann’s murder, he told his brother-in-law, “Donnie, I would be better off dead.” He told his wife and friends that he was in trouble with the law, that he had killed two state troopers and stabbed one of them in the throat.

His wife dyed his hair black, and he traded his Ford Torino, silver gray with a brown vinyl top, for a blue Mustang at the used car lot in Gleason, Tenn. That’s what led investigators to Coe. Not long after he left the lot in the Mustang, the chief of police stopped by to ask the owners whether they had traded cars with anyone lately. The owner’s wife, Althea Jones, said that yes, as a matter of fact, they just traded with a guy with a very sloppy hair-dye job. She had noticed black smudge marks on Coe’s forehead.

There was little physical evidence against Coe. His car yielded no evidence of sexual assault, and no hair or fingerprints were found for use against him. However, fecal material was found underneath the foreskin of his penis, and stains on the interior of his pants matched stains found on Cary Ann’s underpants.

At his trial, which was moved from Weakley County to Memphis, Coe used an insanity defense. Six years earlier, he was declared incompetent to stand trial in Florida for trying to rape and stab a woman. He was sent to a mental hospital, diagnosed as suffering from “an explosive personality disorder,” given Thorazine, and eventually released. One expert witness in his murder trial said his childhood was “like something out of Erskine Caldwell.” His father, who also had spent time in a mental hospital, sexually abused Coe and forced him to watch while he sexually abused Coe’s sisters. Several experts testified Coe wasn’t legally insane at the time of the murder, but others said he was psychotic and strung out on drugs and booze.

Little Michael Stout identified Coe as the man in the car who took away Cary Ann. Michael’s grandmother identified Coe’s Ford Torino as the car she saw outside her house.

The jury convicted Coe of first-degree murder, rape, and kidnapping. At his sentencing hearing, the prosecutor urged the jury “to be true to your conscience, to be true to God.” In asking for the death penalty, he said the Bible teaches “whosoever sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed.” He told the jurors, “I just want to ask you to put your mind at rest if that in any way has created any conflict, because there’s certainly foundation for capital punishment in the Bible and in the Scriptures themselves.”

During the 19 years of appeals since his death sentence, Coe’s case has outraged the public and galvanized the victim’s rights movement in Tennessee. When conservative politicians denounce the seemingly endless nature of capital cases, Coe’s is Exhibit No. 1.