Executed February 12, 2014 08:17 p.m. EST by Lethal Injection in Florida

7th murderer executed in U.S. in 2014

1367th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Florida in 2014

83rd murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(8) |

|

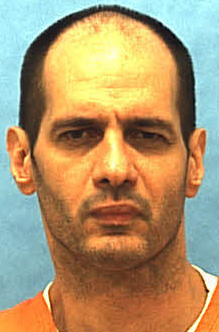

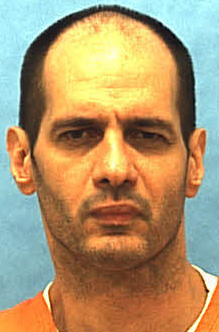

Juan Carlos Chavez W / M / 28 - 46 |

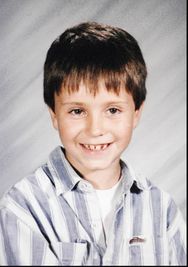

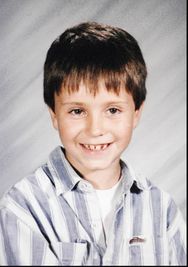

Samuel James Ryce W / M / 9 |

Citations:

Chavez v. State, 832 So.2d 730 (Fla. 2002). (Direct Appeal)

Chavez v. State, 12 So.3d 199 (Fla. 2009). (PCR)

Chavez v. Secretary, 647 F.3d 1057 (11th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Final / Special Meal:

Steak, French fries, strawberry ice cream, mixed fruit and mango juice.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Florida Department of Corrections

DC Number: M18034

Date of Offense: 9/11/1995

County: ORANGE

Date Sentenced: 11/23/1998

Date Received: 12/9/1998

Date of Execution: 2/12/2014

Current Prison Sentence History:

09/11/1995 1ST DG MUR/PREMED. OR ATT. 11/23/1998 ORANGE 9811700 DEATH SENTENCE

09/11/1995 SEX BAT BY ADULT/VCTM LT 12 11/23/1998 ORANGE 9811700 SENTENCED TO LIFE

09/11/1995 KIDNAP;COMM.OR FAC.FELONY 11/23/1998 ORANGE 9811700 SENTENCED TO LIFE

Incarceration History: 12/09/1998 to 02/12/2014

"Fla. man executed in boy's rape, murder," by Tamara Lush. (Associated Press 02.13.14)

STARKE, Fla. -- The father of a 9-year-old South Florida boy raped and murdered in 1995 said he hopes the killer's execution sends a strong signal to other would-be child molesters and abductors. "Don't kill the child. Because if you do, people will not forget, they will not forgive. We will hunt you down and we will put you to death," said Don Ryce, whose son Jimmy Ryce was kidnapped at gunpoint after getting off a school bus. He spoke Wednesday night after Juan Carlos Chavez, 46, was executed by lethal injection at Florida State Prison. Chavez was pronounced dead at 8:17 p.m., according to Gov. Rick Scott's office.

Chavez abducted Jimmy Ryce at gunpoint after the boy got off a school bus on Sept. 11, 1995, in rural Miami-Dade County. Testimony showed Chavez raped the boy, shot him when he tried to escape, then dismembered his body and hid the parts in concrete-covered planters. Ryce's parents turned the tragedy's pain into a push for stronger U.S. laws regarding confinement of sexual predators and improved police procedures in missing child cases. Their foundation provided hundreds of free canines to law enforcement agencies to aid in searches for children.

Despite an intensive search in 1995 by police and volunteers, regular appeals for help through the media and distribution of flyers about Jimmy, it wasn't until three months later that Chavez's landlady discovered the boy's book bag and the murder weapon — a revolver Chavez had stolen from her house — in the trailer where Chavez lived. Chavez later confessed to police and led them to Jimmy's remains. He was tried and found guilty of murder, sexual battery and kidnapping.

Chavez made no final statement in the death chamber, but did submit a statement laced with religious references. He said he had found forgiveness in religion and that he wished for "unfailing love be upon us, upon me, upon those who today take the life out of this body, as well as those who in their blindness or in their pain desire my death. God bless us all."

Don Ryce had said recently that he and his wife had become determined to turn their son's horrific slaying into something positive, in part because they felt they owed something to all the people who tried to help find him. They also refused to wallow in misery. "You've got to do something or you do nothing. That was just not the way we wanted to live the rest of our lives," he said. The Ryces created the Jimmy Ryce Center for Victims of Predatory Abduction, a nonprofit organization based in Vero Beach that works to increase public awareness and education about sexual predators. It also provides counseling for parents of victims and helps train law enforcement agencies in ways to respond to missing children cases.

The organization has also provided, free of charge, more than 400 bloodhounds to police departments around the country and abroad. Ryce said if police searching for Jimmy had bloodhounds they might have found him in time. The Ryces also helped persuade then-President Bill Clinton to sign an executive order allowing missing-child flyers to be posted in federal buildings, which they had been prevented from doing for their own son. Another accomplishment was 1998 passage in Florida of the Jimmy Ryce Act, versions of which have also been adopted in other states. Under the law, sexual predators found to be still highly dangerous can be detained through civil commitment even after they have served their prison sentences. Such people must prove they have been rehabilitated before they can be released. Chavez had no criminal record, so the law would not have affected him.

The Florida Supreme Court refused Wednesday morning to stay the execution to allow Chavez time to pursue appeals, and the U.S. Supreme Court followed suit hours later. The appeals prompted a more than two-hour delay in Chavez's scheduled execution.

"Juan Carlos Chavez executed for 1995 rape, murder of Jimmy Ryce," by Tamara Lush. (AP 2/12/14)

STARKE, Fla. — A man was executed Wednesday night in Florida for raping and killing a 9-year-old boy 18 years ago, a death that spurred the victim's parents to press nationwide for stronger sexual predator confinement laws and better handling of child abduction cases . . . . MIAMI (AP) — In the 18 years since 9-year-old Jimmy Ryce's rape and murder, his father and his mother, before her death, tried to alleviate the pain of their family's tragedy by working for society's good. They pushed for new laws regarding confinement of sexual predators and worked to improve police procedures in missing child cases. But with the killer's scheduled execution set for Wednesday, Don Ryce said the death of Juan Carlos Chavez will finally bring some measure of justice. Barring a successful last-minute appeal, Chavez is scheduled to die by lethal injection at Florida State Prison in Starke . . . .

"Cuban immigrant executed for 1995 murder of Florida boy," by Bill Cotterell. (Thu Feb 13, 2014)1

(Reuters) - A Cuban immigrant was executed by lethal injection on Wednesday for the 1995 kidnapping, rape and murder of a 9-year-old south Florida boy, a spokeswoman for the governor said. Juan Carlos Chavez, who confessed to the murder of Jimmy Ryce, was executed at the Florida State Prison at Starke, Florida, at 8:17 p.m. EST (0117 GMT Thursday), said Jackie Schutz, a spokeswoman for Governor Rick Scott.

A Florida law passed in the wake of the killing cleared the way for imprisoned sexual offenders to be held after their release if found likely to repeat their crimes. The law has been replicated across the United States. The execution, attended by Ryce's father, was briefly delayed by a last-minute appeal that the U.S. Supreme Court denied.

The Department of Corrections said Chavez had a last meal of steak, French fries, strawberry ice cream, mixed fruit and mango juice in the afternoon. He had no visitors, officials said. In a written statement released by the state after his death, Chavez expressed no remorse, saying that "None of us can pass judgment on another (man's) sins." Chavez wrote, "I doubt that there is anything I can say that would satisfy everybody, even less those who see in me nothing more (than) someone deserving of punishment."

Chavez, who worked as a farmhand and had no criminal history, kidnapped the boy at gunpoint as he got off a school bus in Redland, an agricultural area of south Miami-Dade County. He took Ryce to his trailer and raped him. When the boy tried to escape, Chavez shot him in the back, dismembered him and hid his body in plastic pots. The boy's disappearance shook south Florida and garnered national attention. Hundreds of volunteers signed up for the search and his parents held a stream of press conferences. Three months after disappearing, Jimmy's remains were found near Chavez's trailer after his landlord found the boy's school bag.

Chavez arrived in south Florida on a raft from Cuba with two others in 1991 and was working as a farmhand at the time of the murder. Little is known about his background or family, who remained in Cuba. The Florida Supreme Court upheld Chavez's 1998 conviction and death sentence. Subsequent appeals were denied.

After Jimmy's death Don Ryce and his mother Claudine, who died in 2009, became advocates for abducted and missing children. They opened a center for abduction victims in south Florida and have provided hundreds of bloodhounds to law enforcement nationwide to help find missing children. The Ryces were on hand as President Bill Clinton in 1996 signed an order instructing federal agencies to post missing-children posters in federal buildings.

Don Ryce, a retired lawyer now living near central Florida, told the Miami Herald recently that the loss of his son broke the heart of his wife and his daughter. "This is the kind of loss that never gets right, that you never completely recover from," Ryce told the paper. His daughter, Jimmy's half-sister, Martha, committed suicide in 2012. After the execution Don Ryce told reporters that he had a message for future child predators. "Don't kill the child. Don't kill the child," Ryce said. "Because if you do, people will not forget. They will not forgive. We will hunt you down, and we will put you to death."

"Juan Carlos Chavez executed for 1995 killing of Jimmy Ryce." (10:19 p.m. EST, February 12, 2014)

STARKE— A Cuban immigrant was executed by lethal injection Wednesday for the 1995 kidnapping, rape and murder of 9-year-old Jimmy Ryce, a spokesman for the governor said. Juan Carlos Chavez, who confessed to the murder of Ryce, who lived in south Miami-Dade County, was executed at the Florida State Prison at Starke at 8:17 p.m., said Jackie Schutz, a press aide for Governor Rick Scott.

A Florida law passed in the wake of the killing cleared the way for imprisoned sexual offenders to be held after their release if found likely to repeat their crimes. The law has been replicated across the United States.

The execution, attended by Ryce's father, was briefly delayed by a last-minute appeal by Chavez's lawyers which the U.S. Supreme Court denied.

The Department of Corrections said Chavez had a last meal of steak, French fries, strawberry ice cream, mixed fruit and mango juice in the afternoon. He had no visitors, the DOC said. Chavez said nothing to witnesses in the death chamber. But in a final written statement released by the state after his death, Chavez expressed no remorse, saying that "none of us can pass judgment on another [man's sins. "I doubt that there is anything I can say that would satisfy everybody, even less those who see in me nothing more [than] someone deserving of punishment."

Chavez, who worked as a farmhand and had no criminal history, kidnapped the boy at gunpoint as he got off a school bus. He took Ryce to his trailer and raped him. When the boy tried to escape, Chavez shot him in the back, dismembered him and hid his body in concrete-filled plastic pots. The boy's disappearance garnered national attention. Hundreds of volunteers signed up for the search and his parents held a stream of news conferences. Three months after disappearing, Jimmy's remains were found near Chavez's trailer after his landlord found the boy's school bag. The Florida Supreme Court upheld Chavez's 1998 conviction and death sentence. Subsequent appeals were denied, though Chavez last week filed a final appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court.

Jimmy's father, Don Ryce, spoke to reporters shortly after 9 p.m. Wednesday. He said: "Nineteen years ago, Juan Carlos Chavez was faced with a choice. He kidnapped my son Jimmy, he sexually assaulted him and [then] it was time to decide would he let him live or would he take his life. We know what he decided to do and the choice he made. "As a result of that choice, he died today. This choice unfortunately will come up in the future in other cases when someone has committed a crime against a child, molested one, raped one or kidnapped one. They also will be faced with the same kind of choice that Chavez was faced with so long ago. "When they do, when they’re processing what they think they want to do, I hope they will remember that it will be burned in their mind, four words: Don’t kill the child, don’t kill the child, because if they do people will not forget, they will not forgive, we will hunt you down and we will put you to death."

Ted Ryce, Jimmy's older brother, said: "Many people have asked why I decided to come today. I did not come today to celebrate Juan Carlos’s execution. In fact, I did not want to come. So why did I come? I came here to represent my brother Jimmy Ryce. I came here for my sister Martha and my mother, Claudine. I came here today because I believe in the justice that has been served on this day. I am here to support that belief.

"I’m also here today as a symbol of strength to show you that in spite of all the terrible tragedies we’ve been through, my father and I still stand strong and strength is something that is sorely lacking in our country today. Many people did not believe that Juan Carlos Chavez should be put to death for his horrible crime of raping and murdering my brother Jimmy Ryce. I believe this comes from a place of weakness, not strength. It comes from not being able to face the atrociousness of some men’s actions and punish them on a level commensurate with their crime. "But we must be strong. We must do what it takes to send a clear message to other child predators that if they go after children, if they kill children, that they will die at the executioner’s hands. Today will bring no closure for my family. As my father has stated, 'Closure does not exist,' but the justice served this day after a painful 19 years will end the chapter on this part of our life and now we look forward to moving on. Thank you."

"Jimmy Ryce’s killer executed." (Associated Press February 12, 2014)

STARKE — A man was executed Wednesday night in Florida for raping and killing a 9-year-old boy 18 years ago, a death that spurred the victim’s parents to press nationwide for stronger sexual predator confinement laws and better handling of child abduction cases. Juan Carlos Chavez, 46, was pronounced dead at 8:17 p.m. Wednesday after a lethal injection at Florida State Prison, according to Gov. Rick Scott’s office. Chavez made no final statement in the death chamber, but did submit a statement laced with religious references in writing. He moved his feet frequently after the injection began at 8:02 p.m. but two minutes later stopped moving.

Chavez abducted Jimmy Ryce at gunpoint after the boy got off a school bus on Sept. 11, 1995, in rural Miami-Dade County. Testimony showed Chavez raped the boy, shot him when he tried to escape, then dismembered his body and hid the parts in concrete-covered planters.

Ryce’s parents turned the tragedy’s pain into a push for stronger U.S. laws regarding confinement of sexual predators and improved police procedures in missing child cases. Their foundation provided hundreds of free canines to law enforcement agencies to aid in searches for children. The boy’s father, 70-year-old Don Ryce, witnessed the execution along with his son Ted, 37. They told reporters outside the prison that the execution closes a long, painful chapter and hopefully sends a powerful message to other would-be child abductors. “Don’t kill the child. Because if you do, people will not forget, they will not forgive. We will hunt you down and we will put you to death,” Ryce said.

Despite an intensive search in 1995 by police and volunteers, regular appeals for help through the media and distribution of flyers about Jimmy, it wasn’t until three months later that Chavez’s landlady discovered the boy’s book bag and the murder weapon - a revolver Chavez had stolen from her hous e - in the trailer where Chavez lived. Chavez later confessed to police and led them to Jimmy’s remains. He was tried and found guilty of murder, sexual battery and kidnapping.

In his written statement, Chavez said he had found forgiveness in religion and was not afraid of death. He said he wished for “unfailing love be upon us, upon me, upon those who today take the life out of this body, as well as those who in their blindness or in their pain desire my death. God bless us all.” Chavez’s latest state and federal court appeals focused on claims that Florida’s lethal injection procedure is unconstitutional, that he didn’t get due process during clemency hearings and that he should have an execution stay to pursue further appeals. The Florida Supreme Court, however, refused Wednesday morning to stay the execution to allow Chavez time to pursue those challenges, and the U.S. Supreme Court followed suit hours later. The appeals prompted a more than two-h our delay in Chavez’s execution.

The victim’s father said recently that he and his wife had become determined to turn their son’s horrific slaying into something positive, in part because they felt they owed something to all who tried to help find him. They also refused to despair. “You’ve got to do something or you do nothing. That was just not the way we wanted to live the rest of our lives,” he said.

The Ryces created the Jimmy Ryce Center for Victims of Predatory Abduction, a nonprofit organization based in Vero Beach that promotes public awareness and education about sexual predators. It also counsels parents of victims and helps train law enforcement agencies in responding to missing children cases. The organization also has provided, free of charge, more than 400 bloodhounds to police departments nationwide and abroad. Ryce said if police searching for Jimmy had bloodhounds they might have found him in time. The Ryces also helped persuade then-President Bill Clinton to sign an executive order allowing missing-child flyers to be posted in federal buildings, which they had been prevented from doing for their own son.

Another accomplishment was 1998 passage in Florida of the Jimmy Ryce Act, versions of which have been adopted in other states. Under the law, sexual predators found to be still highly dangerous can be detained through civil commitment even after they have served their prison sentences. Such people must prove they have been rehabilitated before they can be released. Chavez had no criminal record, so the law would not have affected him. Chavez’s only visitor Wednesday was his spiritual adviser, prison officials said.

Following is a list of inmates executed since Florida resumed executions in 1979:

1. John Spenkelink, 30, executed May 25, 1979, for the murder of traveling companion Joe Szymankiewicz in a Tallahassee hotel room.

2. Robert Sullivan, 36, died in the electric chair Nov. 30, 1983, for the April 9, 1973, shotgun slaying of Homestead hotel-restaurant assistant manager Donald Schmidt.

3. Anthony Antone, 66, executed Jan. 26, 1984, for masterminding the Oct. 23, 1975, contract killing of Tampa private detective Richard Cloud.

4. Arthur F. Goode III, 30, executed April 5, 1984, for killing 9-year-old Jason Verdow of Cape Coral March 5, 1976.

5. James Adams, 47, died in the electric chair on May 10, 1984, for beating Fort Pierce millionaire rancher Edgar Brown to death with a fire poker during a 1973 robbery attempt.

6. Carl Shriner, 30, executed June 20, 1984, for killing 32-year-old Gainesville convenience-store clerk Judith Ann Carter, who was shot five times.

7. David L. Washington, 34, executed July 13, 1984, for the murders of three Dade County residents _ Daniel Pridgen, Katrina Birk and University of Miami student Frank Meli _ during a 10-day span in 1976.

8. Ernest John Dobbert Jr., 46, executed Sept. 7, 1984, for the 1971 killing of his 9-year-old daughter Kelly Ann in Jacksonville..

9. James Dupree Henry, 34, executed Sept. 20, 1984, for the March 23, 1974, murder of 81-year-old Orlando civil rights leader Zellie L. Riley.

10. Timothy Palmes, 37, executed in November 1984 for the Oct. 19, 1976, stabbing death of Jacksonville furniture store owner James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Ronald John Michael Straight, executed May 20, 1986.

11. James David Raulerson, 33, executed Jan. 30, 1985, for gunning down Jacksonville police Officer Michael Stewart on April 27, 1975.

12. Johnny Paul Witt, 42, executed March 6, 1985, for killing, sexually abusing and mutilating Jonathan Mark Kushner, the 11-year-old son of a University of South Florida professor, Oct. 28, 1973.

13. Marvin Francois, 39, executed May 29, 1985, for shooting six people July 27, 1977, in the robbery of a ``drug house'' in the Miami suburb of Carol City. He was a co-defendant with Beauford White, executed Aug. 28, 1987.

14. Daniel Morris Thomas, 37, executed April 15, 1986, for shooting University of Florida associate professor Charles Anderson, raping the man's wife as he lay dying, then shooting the family dog on New Year's Day 1976.

15. David Livingston Funchess, 39, executed April 22, 1986, for the Dec. 16, 1974, stabbing deaths of 53-year-old Anna Waldrop and 56-year-old Clayton Ragan during a holdup in a Jacksonville lounge.

16. Ronald John Michael Straight, 42, executed May 20, 1986, for the Oct. 4, 1976, murder of Jacksonville businessman James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Timothy Palmes, executed Jan. 30, 1985.

17. Beauford White, 41, executed Aug. 28, 1987, for his role in the July 27, 1977, shooting of eight people, six fatally, during the robbery of a small-time drug dealer's home in Carol City, a Miami suburb. He was a co-defendant with Marvin Francois, executed May 29, 1985.

18. Willie Jasper Darden, 54, executed March 15, 1988, for the September 1973 shooting of James C. Turman in Lakeland.

19. Jeffrey Joseph Daugherty, 33, executed March 15, 1988, for the March 1976 murder of hitchhiker Lavonne Patricia Sailer in Brevard County.

20. Theodore Robert Bundy, 42, executed Jan. 24, 1989, for the rape and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach of Lake City at the end of a cross-country killing spree. Leach was kidnapped Feb. 9, 1978, and her body was found three months later some 32 miles west of Lake City.

21. Aubry Dennis Adams Jr., 31, executed May 4, 1989, for strangling 8-year-old Trisa Gail Thornley on Jan. 23, 1978, in Ocala.

22. Jessie Joseph Tafero, 43, executed May 4, 1990, for the February 1976 shooting deaths of Florida Highway Patrolman Phillip Black and his friend Donald Irwin, a Canadian constable from Kitchener, Ontario. Flames shot from Tafero's head during the execution.

23. Anthony Bertolotti, 38, executed July 27, 1990, for the Sept. 27, 1983, stabbing death and rape of Carol Ward in Orange County.

24. James William Hamblen, 61, executed Sept. 21, 1990, for the April 24, 1984, shooting death of Laureen Jean Edwards during a robbery at the victim's Jacksonville lingerie shop.

25. Raymond Robert Clark, 49, executed Nov. 19, 1990, for the April 27, 1977, shooting murder of scrap metal dealer David Drake in Pinellas County.

26. Roy Allen Harich, 32, executed April 24, 1991, for the June 27, 1981, sexual assault, shooting and slashing death of Carlene Kelly near Daytona Beach.

27. Bobby Marion Francis, 46, executed June 25, 1991, for the June 17, 1975, murder of drug informant Titus R. Walters in Key West.

28. Nollie Lee Martin, 43, executed May 12, 1992, for the 1977 murder of a 19-year-old George Washington University student, who was working at a Delray Beach convenience store.

29. Edward Dean Kennedy, 47, executed July 21, 1992, for the April 11, 1981, slayings of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Howard McDermon and Floyd Cone after escaping from Union Correctional Institution.

30. Robert Dale Henderson, 48, executed April 21, 1993, for the 1982 shootings of three hitchhikers in Hernando County. He confessed to 12 murders in five states.

31. Larry Joe Johnson, 49, executed May 8, 1993, for the 1979 slaying of James Hadden, a service station attendant in small north Florida town of Lee in Madison County. Veterans groups claimed Johnson suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

32. Michael Alan Durocher, 33, executed Aug. 25, 1993, for the 1983 murders of his girlfriend, Grace Reed, her daughter, Candice, and his 6-month-old son Joshua in Clay County. Durocher also convicted in two other killings.

33. Roy Allen Stewart, 38, executed April 22, 1994, for beating, raping and strangling of 77-year-old Margaret Haizlip of Perrine in Dade County on Feb. 22, 1978.

34. Bernard Bolander, 42, executed July 18, 1995, for the Dade County murders of four men, whose bodies were set afire in car trunk on Jan. 8, 1980.

35. Jerry White, 47, executed Dec. 4, 1995, for the slaying of a customer in an Orange County grocery store robbery in 1981.

36. Phillip A. Atkins, 40, executed Dec. 5, 1995, for the molestation and rape of a 6-year-old Lakeland boy in 1981.

37. John Earl Bush, 38, executed Oct. 21, 1996, for the 1982 slaying of Francis Slater, an heir to the Envinrude outboard motor fortune. Slater was working in a Stuart convenience store when she was kidnapped and murdered.

38. John Mills Jr., 41, executed Dec. 6, 1996, for the fatal shooting of Les Lawhon in Wakulla and burglarizing Lawhon's home.

39. Pedro Medina, 39, executed March 25, 1997, for the 1982 slaying of his neighbor Dorothy James, 52, in Orlando. Medina was the first Cuban who came to Florida in the Mariel boat lift to be executed in Florida. During his execution, flames burst from behind the mask over his face, delaying Florida executions for almost a year.

40. Gerald Eugene Stano, 46, executed March 23, 1998, for the slaying of Cathy Scharf, 17, of Port Orange, who disappeared Nov. 14, 1973. Stano confessed to killing 41 women.

41. Leo Alexander Jones, 47, executed March 24, 1998, for the May 23, 1981, slaying of Jacksonville police Officer Thomas Szafranski.

42. Judy Buenoano, 54, executed March 30, 1998, for the poisoning death of her husband, Air Force Sgt. James Goodyear, Sept. 16, 1971.

43. Daniel Remeta, 40, executed March 31, 1998, for the murder of Ocala convenience store clerk Mehrle Reeder in February 1985, the first of five killings in three states laid to Remeta.

44. Allen Lee ``Tiny'' Davis, 54, executed in a new electric chair on July 8, 1999, for the May 11, 1982, slayings of Jacksonville resident Nancy Weiler and her daughters, Kristina and Katherine. Bleeding from Davis' nose prompted continued examination of effectiveness of electrocution and the switch to lethal injection.

45. Terry M. Sims, 58, became the first Florida inmate to be executed by injection on Feb. 23, 2000. Sims died for the 1977 slaying of a volunteer deputy sheriff in a central Florida robbery.

46. Anthony Bryan, 40, died from lethal injection Feb. 24, 2000, for the 1983 slaying of George Wilson, 60, a night watchman abducted from his job at a seafood wholesaler in Pascagoula, Miss., and killed in Florida.

47. Bennie Demps, 49, died from lethal injection June 7, 2000, for the 1976 murder of another prison inmate, Alfred Sturgis. Demps spent 29 years on death row before he was executed.

48. Thomas Provenzano, 51, died from lethal injection on June 21, 2000, for a 1984 shooting at the Orange County courthouse in Orlando. Provenzano was sentenced to death for the murder of William ``Arnie'' Wilkerson, 60.

49. Dan Patrick Hauser, 30, died from lethal injection on Aug. 25, 2000, for the 1995 murder of Melanie Rodrigues, a waitress and dancer in Destin. Hauser dropped all his legal appeals.

50. Edward Castro, died from lethal injection on Dec. 7, 2000, for the 1987 choking and stabbing death of 56-year-old Austin Carter Scott, who was lured to Castro's efficiency apartment in Ocala by the promise of Old Milwaukee beer. Castro dropped all his appeals.

51. Robert Glock, 39 died from lethal injection on Jan. 11, 2001, for the kidnapping murder of a Sharilyn Ritchie, a teacher in Manatee County. She was kidnapped outside a Bradenton shopping mall and taken to an orange grove in Pasco County, where she was robbed and killed. Glock's co-defendant Robert Puiatti remains on death row.

52. Rigoberto Sanchez-Velasco, 43, died of lethal injection on Oct. 2, 2002, after dropping appeals from his conviction in the December 1986 rape-slaying of 11-year-old Katixa ``Kathy'' Ecenarro in Hialeah. Sanchez-Velasco also killed two fellow inmates while on death row.

53. Aileen Wuornos, 46, died from lethal injection on Oct. 9, 2002, after dropping appeals for deaths of six men along central Florida highways.

54. Linroy Bottoson, 63, died of lethal injection on Dec. 9, 2002, for the 1979 murder of Catherine Alexander, who was robbed, held captive for 83 hours, stabbed 16 times and then fatally crushed by a car.

55. Amos King, 48, executed by lethal inection for the March 18, 1977 slaying of 68-year-old Natalie Brady in her Tarpon Spring home. King was a work-release inmate in a nearby prison.

56. Newton Slawson, 48, executed by lethal injection for the April 11, 1989 slaying of four members of a Tampa family. Slawson was convicted in the shooting deaths of Gerald and Peggy Wood, who was 8 1/2 months pregnant, and their two young children, Glendon, 3, and Jennifer, 4. Slawson sliced Peggy Wood's body with a knife and pulled out her fetus, which had two gunshot wounds and multiple cuts.

57. Paul Hill, 49, executed for the July 29, 1994, shooting deaths of Dr. John Bayard Britton and his bodyguard, retired Air Force Lt. Col. James Herman Barrett, and the wounding of Barrett's wife outside the Ladies Center in Pensacola.

58. Johnny Robinson, died by lethal injection on Feb. 4, 2004, for the Aug. 12, 1985 slaying of Beverly St. George was traveling from Plant City to Virginia in August 1985 when her car broke down on Interstate 95, south of St. Augustine. He abducted her at gunpoint, took her to a cemetery, raped her and killed her.

59. John Blackwelder, 49, was executed by injection on May 26, 2004, for the calculated slaying in May 2000 of Raymond Wigley, who was serving a life term for murder. Blackwelder, who was serving a life sentence for a series of sex convictions, pleaded guilty to the slaying so he would receive the death penalty.

60. Glen Ocha, 47, was executed by injection April 5, 2005, for the October, 1999, strangulation of 28-year-old convenience store employee Carol Skjerva, who had driven him to his Osceola County home and had sex with him. He had dropped all appeals.

61. Clarence Hill 20 September 2006 lethal injection Stephen Taylor

62. Arthur Dennis Rutherford 19 October 2006 lethal injection Stella Salamon

63. Danny Rolling 25 October 2006 lethal injection Sonja Larson, Christina Powell, Christa Hoyt, Manuel R. Taboada, and Tracy Inez Paules

64. Ángel Nieves Díaz 13 December 2006 lethal injection Joseph Nagy

65. Mark Dean Schwab 1 July 2008 lethal injection Junny Rios-Martinez, Jr.

66. Richard Henyard 23 September 2008 lethal injection Jamilya and Jasmine Lewis

67. Wayne Tompkins 11 February 2009 lethal injection Lisa DeCarr

68. John Richard Marek 19 August 2009 lethal injection Adela Marie Simmons

69. Martin Grossman 16 February 2010 lethal injection Margaret Peggy Park

70. Manuel Valle 28 September 2011 lethal injection Louis Pena

71. Oba Chandler 15 November 2011 lethal injection Joan Rogers, Michelle Rogers and Christe Rogers

72. Robert Waterhouse 15 February 2012 lethal injection Deborah Kammerer

73. David Alan Gore 12 April 2012 lethal injection Lynn Elliott

74. Manuel Pardo 11 December 2012 lethal injection Mario Amador, Roberto Alfonso, Luis Robledo, Ulpiano Ledo, Michael Millot, Fara Quintero, Fara Musa, Ramon Alvero, Daisy Ricard.

75. Larry Eugene Mann 10 April 2013 lethal injection Elisa Nelson

76. Elmer Leon Carroll 29 May 2013 lethal injection Christine McGowan

77. William Edward Van Poyck 12 June 2013 lethal injection Ronald Griffis

78. John Errol Ferguson 05 August 2013 lethal injection Livingstone Stocker, Michael Miller, Henry Clayton, John Holmes, Gilbert Williams, and Charles Cesar Stinson

79. Marshall Lee Gore 01 October 2013 lethal injection Robyn Novick (also killed Susan Roark but was executed for killing Novick)

80. William Frederick Happ 15 October 2013 lethal injection Angie Crowley

81. Darius Kimbrough 12 November 2013 Lethal Injection Denise Collins

82. Thomas Knight a/k/a Askari Abdullah Muhammad 7 January 2014 lethal injection Sydney and Lillian Gans, Florida Department of Corrections officer Richard Burke

83. Juan Carlos Chavez 12 February 2014 Jimmy Ryce

On the afternoon of September 11, 1995, nine-year-old Samuel James “Jimmy” Ryce disappeared after having been dropped off from his school bus at approximately 3:07 p.m. at a bus stop near his home in the Redlands, a rural area of south Miami Dade County. An extensive and well-publicized search of the area followed, but failed to locate the child.

At that time, the defendant, Juan Carlos Chavez, was living in a trailer on property owned by Susan Scheinhaus. Chavez worked as a handyman for the Scheinhaus family, and was permitted to use their Ford pickup truck to run errands or do other work for the family. As part of his duties, Chavez frequently cared for horses owned by the Scheinhaus family, but housed on property owned by David Santana, which contained an avocado grove. There was also a trailer on that property, referred to throughout Chavez's trial as the “avocado grove trailer” or the “horse-farm trailer.”

In August or September of 1995, Mrs. Scheinhaus reported to the police several times that items (including a handgun and some jewelry) were missing from her residence. Although she suspected Chavez, she lacked evidence of his culpability. She testified at trial that, in November, she had decided to obtain the evidence required to pursue her claim. With the help of a locksmith, on December 5, 1995, while Chavez was away for the day, Mrs. Scheinhaus and her son, Edward Scheinhaus (“Ed”), entered the trailer located on her property which Chavez occupied. She found the handgun-which she later identified in court as a gun she had purchased in April of 1989 - in plain view on a counter opposite the trailer door. As Mrs. Scheinhaus continued to look inside the trailer, she discovered, in the closet area, a book bag which was partially open. Looking inside the bag, she saw papers and books. The work appeared to be in a child's handwriting, and she noticed the name “Jimmy Ryce.” She also observed this name on one of the books. When Mrs. Scheinhaus asked her son to look at the items, he also recognized the child's name. As a result of this discovery, Mrs. Scheinhaus notified the FBI.

When Chavez returned to the Scheinhaus residence at about 7:15 on the evening of December 6, armed FBI agents quickly surrounded and secured him. After being patted down, he agreed to go with Metro Dade Police officers, who were also present, to the station for questioning. Chavez's detention included a questioning process that was punctuated by regular refreshment, food, bathroom breaks and a rest period, and interspersed with two outings returning to the Scheinhaus and Santana properties in southern Miami Dade County. Although Chavez was first brought to the police station on the night of December 6, he did not sleep until shortly after midnight on December 7. Detective Luis Estopinan, who was bilingual, conducted most of the questioning, although other officers also participated. Various police detectives, an FBI agent, Mrs. Scheinhaus and an independent interpreter all had opportunities to observe Chavez at various times throughout this period. Chavez was consistently described as alert and articulate during this time, and no one observed police detectives mistreating Chavez in any way throughout the period of questioning. He received repeated warnings and instructions in accordance with Miranda, and indicated that he fully understood them on four occasions during the period of interrogation.

Over the course of the interrogation, and after having been repeatedly advised of his Miranda rights and knowingly waiving them, Chavez provided several versions of his involvement in Jimmy's disappearance. As law enforcement officers engaged in a contemporaneous investigation of Chavez's changing narratives, he agreed to accompany officers on two occasions to visit the horse farm property and the Scheinhaus property, where he showed them the location of the events he had recounted had transpired. On those occasions, Chavez was asked to reveal where the boy's remains were located, to permit Jimmy's family to have closure. After the physical evidence resulting from this contemporaneous investigation totally discredited each version of events which Chavez had initially proposed, Chavez agreed to tell the truth. However, Chavez explained that, before he would disclose the location of Jimmy's remains, he wanted the officers to guarantee that he would receive the death penalty. Estopinan advised Chavez that he could not guarantee that the death penalty would be imposed. However, Chavez continued to talk, asserting that the events would not have happened had he not been sexually battered by a relative in Cuba.

Estopinan told Chavez that he “felt that it was time for him to be truthful and tell us what really happened to Jimmy, and went back and began to ask him about Jimmy and where Jimmy was located. We wanted to find Jimmy.” A break followed this inquiry and then Chavez reiterated to Sergeant Jimenez the most recent account which he had given Estopinan. Chavez then went to the restroom for another break and, upon returning to the interview room, informed the officers that they were now going to hear the truth: “What do you want to know? I'll tell you what happened to Jimmy Ryce.” Chavez proceeded to admit to Estopinan and Jimenez that he had abducted Jimmy at gunpoint, traveled to the horse ranch, and sexually assaulted Jimmy before finally shooting him. Estopinan explained that the officers would need details from Chavez, and requested permission to take a sworn statement. Chavez agreed to continue the questioning, and Estopinan and Jimenez “began to get details” about what had happened to Jimmy Ryce.

At trial, Estopinan testified regarding the final version of Chavez's statement. Chavez said that he had observed young children playing in water on his way home from Home Depot at approximately 3 p.m. Some of the boys were wearing just their underwear, and “as he saw the young boys wearing just their underwear, he took an interest in them.” After observing the children, Chavez drove off, but returned a short while later, because he “still had a mental picture of what happened, meaning that he saw the young boys in their underwear by the canal bank, and decided that he wanted to take another look.” Estopinan testified: "And while this is occurring, he was driving on the avenue, he sees a figure of a person, and then he realizes it was a young boy that he saw. At the same time he sees the young boy who later turns out to be Jimmy Ryce, again he's thinking about the young boys who are at the canal bank. He said at this point he's feeling something sexual and ... that he has a mental picture in his mind of the young boys in the canal with their underwear and he's also picturing Jimmy Ryce the young boy.

As he's driving the pickup truck in the opposite direction of Jimmy Ryce, he said at the time he had with him the Scheinhaus revolver, the Taurus, .38 caliber. And he said at this time Jimmy is walking on the left side of the road, and what he did is driving on the opposite side, he begins to drive on the opposite side of the traffic and drives and stops right in front of Jimmy Ryce causing him to stop. The minute that Jimmy stops, he stops the truck, he gets out of the truck with the gun in his hand and tells Jimmy at gunpoint, do you want to die? And Jimmy made a comment to him, no. And he told Jimmy in English to get inside the truck. And Jimmy responds by getting into the truck via the driver's side door. Once Jimmy is inside the pickup truck, Jimmy removes his backpack and puts it between his legs and he Chavez gets into the truck with Jimmy, still holding the handgun. It's at that point he takes the revolver and he places it underneath his lap and tells Jimmy to put his head down so Jimmy wouldn't be seen by anyone. And at that point he tells me that he drives back to the horse ranch where the trailer was located. He told me that Jimmy left his backpack inside the pickup truck.

Once they both exit the pickup truck, both him and Jimmy at his direction they go inside the trailer that's located inside the horse ranch. He goes on to explain that once inside the trailer he tells Jimmy to sit down on the bed. Jimmy complies. And that he sits on a black office chair close to Jimmy by the entrance and he begins to talk to Jimmy, he notices that Jimmy is, he's nervous and he's scared and Jimmy begins sobbing. And while this is occurring, Jimmy began to ask him, why did you take me? And Chavez explains to him, well, why do you think I took you, things to that effect. He wants Jimmy to answer his own questions. He goes on to explain that at this point he feels like doing something sexual and that he tells Jimmy to remove his clothing. He said Jimmy complied by removing his shirt, his shorts, his sneakers and he wasn't sure if Jimmy was wearing socks or not. And then Jimmy remains in his underwear only, his white underwear he believes. He goes on to tell me that at this point he gets up and he tells Jimmy to also go ahead and remove his underwear. Jimmy complies and removed his underwear. And then he tells Jimmy to lay on the bed in the trailer and Jimmy complies. Jimmy lays on his stomach on the bed. Chavez tells me that he went into the bathroom area of the trailer looking for something. And I asked him, what are you looking for. He told me I was looking for something like a lubricant. And then he goes into the bathroom and he finds a see through plastic container, he said, with some blue lettering on it. And then he took a sample of the contents of the container to see if it would burn, and when it didn't, he came back to where Jimmy was and he placed this, the substance or the lubricant on to Jimmy's rectum, he said, and as he was placing the lubricant on Jimmy's rectum, Jimmy is asking what are you doing. And he mentioned to Jimmy that what do you think is going to happen, things to that effect.

He unzipped his pants, he exposed his penis and he inserted his penis into Jimmy's rectum. He told me right after he inserted his penis in Jimmy's rectum, he again has a mental picture of the young boys in their underwear which he had seen at the canal and he said that he quickly ejaculated, and once he ejaculated inside Jimmy, he said he removed himself." Chavez said that he and Jimmy then dressed and left in the truck, indicating that he had intended to leave Jimmy in the area where he had picked him up. However, upon nearing the area where he had abducted Jimmy, Chavez noticed that police cars were present. Believing “that someone had reported Jimmy missing and they were looking for Jimmy,” Chavez kept Jimmy's head down in the truck and returned to the horse farm. Estopinan testified regarding what transpired when Chavez and Jimmy returned to the horse farm: "He said once inside the trailer, Jimmy is trembling and crying. And Jimmy asked, what's going to happen to me? Are you going to kill me? He noticed that Jimmy was very frightened. And he begins to speak to Jimmy in order to calm him down." Chavez told Estopinan that he tried to calm Jimmy down by asking him questions.

He then explained how he killed Jimmy: "Well, the next thing Chavez mentions happened is he heard a helicopter fly over the horse ranch. It was his opinion he believed the helicopter belonged to the police, that the police were searching for Jimmy. When he heard the helicopter flying over him, he went ahead and held Jimmy close by to him so Jimmy wouldn't go anywhere, and eventually he heard the chopper several times flying over him, and at one point he said he got up and began looking out the window to see if he could see the chopper, the helicopter that is. And while he was looking for the helicopter, Jimmy is still close to the front entrance of the trailer. He said that Jimmy made a dash for the door, Jimmy ran for the door trying to escape. He said that he tried to reach up to Jimmy, but he got tangled on the floor of the bathroom and at that point he said he took out the revolver belonging to Mrs. Scheinhaus, he pointed the handgun in the direction of Jimmy, fired one time hitting him. He said that Jimmy collapsed right by the door and collapsed to the right by the door inside the trailer. He said after he shot Jimmy, he came up to Jimmy, he turned Jimmy around and held Jimmy in his arms and Jimmy took one last breath, he expressed it, and he said that was the last thing Jimmy did."

Chavez described that, to dispose of Jimmy's body, he found a metal barrel inside the trailer at the horse farm, and placed Jimmy's body inside the barrel. He transported the barrel containing the body from the horse farm to the Scheinhaus residence, where he removed the barrel and placed it in Chavez's disabled van, which was parked in the stable area. Chavez removed Jimmy's book bag from the pickup and carried it with him to his own trailer. That night, Chavez looked at some of the note pads inside Jimmy's book bag. Chavez noticed blood on his own clothing and eventually destroyed the clothes. During the night and into the next morning, “all he could think about was what he was going to do with Jimmy's body.” Two or three days later, Chavez attempted to use a backhoe on the Scheinhaus property to dig a hole in which to bury Jimmy, but the machine did not operate properly. Chavez remained concerned, particularly when he noticed that the lid of the barrel which contained Jimmy's body had come off. Chavez pulled Jimmy's body from the barrel onto a piece of plywood, and, from there, his remains fell to the ground. “And he said at that point he went ahead and began to dismember Jimmy's body with the use of a tool.” Chavez described the tool he used to dismember Jimmy's body, and even drew a picture of the implement. He explained that it took him a while to dismember Jimmy's body, as he was becoming sick and vomiting. “But then he completes it and he places three of Jimmy's parts into these three planters. And once he fills these planters with Jimmy's remains, he goes ahead, goes into the stable area of the stable where the building is located and he locates some cement bags. With those cement bags he seals the tops of the planters with cement.”

The oral interview concluded at 10:50 pm on December 8. While an interpreter and a stenographer were being obtained to record a formal statement, Chavez remained in the interview room, and did not further converse with Estopinan until the interpreter arrived. Then, at 11:45 pm, Chavez began to provide a formal statement. Estopinan, Sergeant Jimenez, and the court reporter were present as the statement was obtained. After some preliminary questions, Chavez was again advised of his Miranda rights. At this time, Chavez confirmed that he had voluntarily agreed to waive his first court appearance and that he had given the officers consent to search his property. When the statement was completed, each page of the statement was reviewed, and Chavez made any corrections he desired. He acknowledged in the statement that he was making the transcribed statement voluntarily; that no one had threatened or coerced him into making the statement; and that he had been treated well. Estopinan testified that, at the time he made his sworn statement, Chavez was “polite, cooperative and he was alert.”

Marilu Balbis testified that she was the professional interpreter providing services during Chavez's sworn statement. Ms. Balbis was an independent contractor who had been an interpreter and translator for twelve years. The confession was unusually long, and Ms. Balbis had the opportunity to closely observe Chavez's demeanor. Chavez did not appear sleepy, and was alert. At no point did the detectives give Chavez any answers. Once the confession was finished, Ms. Balbis read each page, word by word, to Chavez to make sure that it was typed correctly. Chavez approved every page by initialing each page at the bottom. Ms. Balbis indicated that the police officers treated Chavez with courtesy, and that she did not observe them threaten or raise their voices toward Chavez.

Officer Michael Byrd recovered the loaded handgun from Chavez's trailer. Byrd also found a poster in Chavez's trailer bearing the likeness of Jimmy Ryce, which he processed as evidence. A box of bullets containing live ammunition, and one spent shell casing, were also found in the trailer. Crime scene technician Elvey Melgarejo testified that, on December 8, 1995, he helped search and process a trailer on a horse/avocado farm. He searched the trailer and found “a tube of JR water-based lubricant” on a shelf inside the trailer. Melgarejo collected a sofa cushion and part of the wood floor of the trailer just inside the front door. These items were packaged for transmittal to serology for processing. Melgarejo also traveled to the Scheinhaus property, where he noticed the three concrete-filled planters and became suspicious that they might contain a cadaver. Fingerprint technician William Miller identified Chavez's fingerprint on the handgun recovered from his trailer. To determine whether fingerprints were present on the handgun, he placed it in a laboratory chamber in which super glue fumes were released, surrounding the handgun and adhering to the residue and oils left by any fingerprints. As a result, a fingerprint matching that of Chavez was found on the firearm. Miller testified that there were “ten points of identification throughout this fingerprint, which is only common to Chavez. It's an absolute and positive identification that his left thumb print made on the weapon.”

On December 8, 1995, Miller also examined the books and notebooks found inside the book bag belonging to Jimmy Ryce. He found Chavez's fingerprint on the front of one notebook found in the book bag. The fingerprint located on the interior of the notebook cover was found to “have sixteen points of identification, a positive identification, based on the left thumb print of Mr. Juan Carlos Chavez against the print which was developed on the inside cover.” Another print of value was located on the textbook entitled Journeys in Science. He found “this particular print of value from this area to be made by the right middle fingerprint of Chavez. I had nine points of identification.” When compared to the prints of Mrs. Scheinhaus and Edward Scheinhaus, the prints on the book bag contents did not match.

Forensic serologist Theresa Merritt of the Metro Dade Police Department testified that she received items for examination on December 8, 1995. She was dispatched to the horse farm to assist crime scene personnel in attempting to determine whether blood was present. Merritt tested a twin-size mattress from the trailer, a cushion present on the bench in the trailer and a cut-out portion of the threshold area from the floor of the trailer. A scraping from the floor area produced a positive result for the presence of blood. Another sample, from a cushion in the trailer, yielded blood scrapings.

Anita Mathews, assistant director of the forensic identity testing laboratory for “LabCorp” of North Carolina, testified that she was “responsible for doing interpretation on the results of the testing that the technologists conduct.” Mathews testified that they were not able to obtain a sufficient quantity or quality of genetic material from samples collected from the body of Jimmy Ryce for testing. However, DNA from the oral swab samples taken from his parents, Don and Claudine Ryce, was compared to the blood found on the floor of the trailer. This comparison produced the conclusion that the blood on the floor was extremely likely to have come from a child of Don and Claudine Ryce. Two other blood samples taken from the floor of the trailer carried the same genetic characteristics. Another blood sample, taken from the cushion found in the trailer, also was consistent with having come from the biological child of the Ryces.

Dr. Roger Mittleman, Chief Medical Examiner for the Dade Medical Examiner's Department, testified that, on December 9, he conducted an examination of the contents of the three planters. The cement in each planter encased the remains of what appeared to be a young boy. The remnants of a cement bag were in at least one of the planters. Dr. Mittleman described the clothing found on Jimmy's body: “It was dressed in this T-shirt and had on jeans and underwear. There was one sneaker on; ?one sneaker was off. There were socks.” The doctor then corrected himself, and stated that only one sock was found on the body. The doctor testified that a body expands as it decomposes due to the breakdown of material and biological processes, causing gases to expand. This process could cause a body placed in a barrel to expand to the point that a lid would be forced off or open. The remains were significantly decomposed. Using dental records from Jimmy's family dentist, a forensic dentist testified that the comparison with the jaw and teeth of the body was so strong that the “skeletal remains” were “positively identified as that of Jimmy Ryce.” An X-Ray of the body cavity revealed a flattened projectile jacket that lodged in the area of the heart and “great vessels.” The bullet entered at the point where the right sixth rib is located, went upward in the body, through the lung and the heart, and exited from the upper left chest Based upon the trajectory of the bullet, the gun would have been pointing slightly upward and below the individual who was shot. However, there was no evidence on the body which would demonstrate how far away the gun was when it was fired.

On December 20, 1995, Detective McColman had transported a tool known as a “bush hook,” which had previously been impounded, to the medical examiner's office. Dr. Mittleman was asked to examine the bush hook to determine if its cutting characteristics were consistent with the injuries inflicted on Jimmy's body. The medical examiner noted that a number of the injuries inflicted on the body during dismemberment were consistent with having been made by the bush hook. However, he also testified that it was possible that more than one instrument had been used. Firearms examiner Thomas Quirk of the Metro-Dade Police Department Crime Laboratory testified that a .38 caliber Taurus model 85 revolver (State's Exhibit 23) was submitted for his examination after it had been processed by the fingerprint section. He also received one aluminum jacket from a projectile recovered from the body of the victim, and two .38 caliber casings-a projectile identified as having come from a red bullet box and a casing that had been fired from a firearm. The two empty .38 caliber shell casings found in Chavez's trailer were fired from the .38 recovered from Chavez's trailer. Quirk testified that the manufacture of the barrel and the rifling process provide microscopic differences which are transferred to the bullet during firing and which repeat, similar to a fingerprint. Also, the projectile jacket recovered by the medical examiner and the lead core (the fatal bullet) were positively identified as having been fired by the gun recovered from Chavez's trailer: “My conclusion is that this bullet was fired in this weapon to the exclusion of all other weapons in the world. This is the gun that fired this bullet.”

After the State rested, Chavez moved for judgment of acquittal, which was denied. Defense counsel specifically argued the State's failure to establish a corpus delicti for the crime of sexual battery. The defense then began the presentation of its case. During the examination of Ed Scheinhaus, Ed explained that he had been under house arrest at the time the kidnaping occurred. He worked from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., and was required to stay at home at all other times, unless he arranged in advance to be away from his house. He had an ankle device, and would be called each day at random times (as controlled by a computer) throughout the period he was confined to his home. When called, he would have to “report in” by placing the ankle bracelet next to a device installed in his home. Chavez also testified in his own defense, stating that he had belonged to a counter-revolutionary group in Cuba. He gave details of his imprisonment (for attempting to escape and for stealing military property) in Cuba, and his eventual escape from the island.

According to his trial testimony, Chavez encountered Ed Scheinhaus at the horse farm trailer after Jimmy had already been killed, and helped Ed to dispose of the boy's body. Chavez testified that, after he was brought to police headquarters in connection with Jimmy's disappearance, he was mistreated. He stated that, when he was placed in the police car, he was told, “Don't do anything stupid or we'll shoot you. We're going to kill you.” He complained that his watch and beeper were taken away from him, and returned only after he gave his final confession. Chavez stated that, when they were interrogating him, he did not know what date or time it was. He said that he was not permitted to sleep, and no one ever offered him a pillow or a blanket. Chavez also claimed that the officers brought the book bag into the interrogation room, and asked Chavez to handle it and look through its contents, which he did. According to Chavez, the police goaded him into making up lies. He stated that the officers suggested details of his confession, and, to avoid deportation, he did whatever they wanted. After the defense rested, the State presented rebuttal testimony. The officers refuted that they had ever threatened Chavez, coerced him, or suggested any part of the confession to him; they denied that they had taken Chavez's watch away or that anyone had hit him;and they testified that he had never mentioned Ed as the perpetrator during the questioning process. Ed Scheinhaus's parole officer testified that Ed (who is in the pest control business) had his permission to travel to take care of a client on the afternoon on which he had received a speeding ticket, and that Ed had shown the ticket to the parole officer himself, without being asked to do so.

He testified that Ed had lost his ankle bracelet once (prior to September 11), and that he had come in that same day to have it replaced with a new one. He said that the file would only reflect times when calls were made to the house and Ed did not respond. He said that he had nothing in the file for the month of September 1995, which indicated that Ed had remained home as required, and that no violations had occurred.

At the close of rebuttal, Chavez renewed all motions, including the motion to suppress his statements, the motion for judgment of acquittal (particularly reiterating that the State had failed to prove the corpus delicti of the charge of sexual battery), and the motion for mistrial, based upon alleged cumulative errors. These motions were denied. The jury was instructed, and, following deliberation, entered verdicts of “guilty” on all of the counts charged. Following the penalty phase of the trial, the jury recommended death by a vote of twelve to zero.

UPDATE: Juan Chazvez was executed for the rape and murder of 9 year old Jimmy Ryce in 1995. Chavez did not make a verbal final statement, but submitted a written statement that read in part: "I doubt there there is anything I can say that would satisfy everybody, even less those who see in me nothing more than someone deserving of punishment." Jimmy's father Don, who is now 70, witnessed the execution along with his son Ted. They told reporters outside the prison that the execution closes a long, painful chapter and hopefully sends a powerful message to other would-be child abductors. "Don't kill the child. Because if you do, people will not forget, they will not forgive. We will hunt you down and we will put you to death," Don Ryce said. Jimmy Ryce's death led to changes in the legal system, and the way police respond to missing child cases. Don Ryce said recently that he and his wife became determined to turn their son's horrific slaying into something positive, in part because they felt they owed something to all the people who tried to help find him. They also refused to wallow in misery. "You've got to do something or you do nothing. That was just not the way we wanted to live the rest of our lives," he said.

The Ryces created the Jimmy Ryce Center for Victims of Predatory Abduction, a nonprofit organization based in Vero Beach that works to increase public awareness and education about sexual predators, provides counseling for parents of victims and helps train law enforcement agencies in ways to respond to missing children cases. The organization has also provided, free of charge, more than 400 bloodhounds to police departments around the country and abroad. Ryce said if police searching for Jimmy had bloodhounds they might have found him in time. Another accomplishment was 1998 passage in Florida of the Jimmy Ryce Act, versions of which have also been adopted in other states. Under the law, sexual predators found to be still highly dangerous can be detained through civil commitment even after they have served their prison sentences. Such people must prove they have been rehabilitated before they can be released. Chavez had no criminal record, so the law would not have affected him.

Florida Commission on Capital Cases

CHAVEZ, Juan Carlos (H/M)

DC # M18034

DOB: 03/16/67

Date of Offense: 09/11/95

Date of Sentence: 11/23/98

Eleventh Judicial Circuit, Dade County, Case #95-037867

Change of Venue from Orange County, Case #98-11700

Sentencing Judge: The Honorable Marc Schumacher

Attorney, Criminal Trial: Edward Koch – Assistant Public Defender

Attorney, Direct Appeal: R. Harper, S. Whittington, & J. Savitz – Private

Attorney, Collateral Appeals: Andrea Norgard – Registry

Circumstances of Offense:

Juan Carlos Chavez was convicted and sentenced to death for the kidnapping, sexual assault and murder of nine-year-old Samuel James “Jimmy” Ryce. Jimmy Ryce disappeared on 09/11/95, after being dropped off by the school bus in Redlands, Florida. Extensive search efforts failed to locate the boy.

Juan Carlos Chavez worked as a handyman for the Scheinhaus family and lived in a trailer located on their property. Chavez also cared for the Scheinhaus’ horses, which were boarded on a farm owned by David Santana. In late August or early September of 1995, Susan Scheinhaus reported to police that several items were missing from her residence, including a handgun and some jewelry. Scheinhaus suspected Chavez, but had no evidence to prove her suspicions. On 12/05/95, Scheinhaus, aided by a locksmith, entered the trailer inhabited by Chavez. Scheinhaus spotted the handgun in plain view. After further examination of the trailer, Scheinhaus found a book bag belonging to Jimmy Ryce. Several items in the book bag, including books and papers had his name written on them. Scheinhaus notified the FBI. On 12/06/95, Chavez was located and taken to the Metro-Dade Police Station for questioning.

During a 55-hour interrogation and having been advised of his rights, Chavez voluntarily and knowingly admitted to abducting, sexually assaulting and killing Jimmy Ryce. Chavez gave a detailed account of the abduction. Chavez confessed that he kidnapped Jimmy at gunpoint and then took him to the horse farm where he sexually assaulted and later shot the boy. Chavez transported the body to the Scheinhaus residence. There he dismembered the boy’s body and hid the parts by cementing them in three large planters. Chavez had no prior incarceration history in the state of Florida.

Trial Summary:

12/06/95 The defendant was arrested.

12/20/95 The defendant was indicted as follows: Count I: First-Degree Murder Count II: Sexual Assault / Victim Under 12 Count III: Kidnapping with a Weapon

09/18/98 The defendant was found guilty on all counts charged in the indictment.

10/29/98 The jury unanimously recommended the death penalty.

11/23/98 The defendant was sentenced as follows: Count I: First-Degree Murder - Death Count II: Sexual Assault / Victim Under 12 - Life Count III: Kidnapping with a Weapon - Life

Appeal Summary:

Florida Supreme Court - Direct Appeal

FSC #94,586

832 So. 2d 730

12/28/98 Appeal filed.

05/30/02 FSC affirmed the convictions and sentence of death.

11/21/02 Rehearing denied in light of revised opinion.

12/20/02 Mandate issued.

United States Supreme Court - Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC #02-10297

539 U.S. 947

04/23/03 Petition filed.

06/23/03 Petition denied.

Circuit Court – 3.851 Motion

CC# 95-37867

07/09/04 Motion filed.

05/05/05 Motion amended.

01/10/07 Evidentiary Hearing held.

03/08/07 CC denied motion.

Florida Supreme Court – 3.851 Motion Appeal

FSC# 07-952

05/23/07 Appeal filed.

06/25/09 Conviction and sentence affirmed.

07/22/09 Mandate issued.

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC# 08-970

05/27/08 Petition filed.

06/25/09 Petition denied.

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 09-6156

130 S.Ct. 501

08/28/09 Petition filed.

11/02/09 Petition denied.

United States District Court, Southern District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

USDC# 10-20399

02/09/10 Petition filed.

07/12/10 Petition dismissed.

08/13/10 Motion for Certificate of Appealability filed.

10/02/10 Motion granted.

United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit – Habeas Appeal

USDC# 10-13840 (Pending)

08/10/10 Appeal filed.

Case Information: On 12/28/98, Chavez filed a Direct Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court. In that appeal, he argued that the police did not have probable cause for his arrest, that the trial court erred in denying his motion to suppress his confession (for numerous reasons) and that the deprivation of his right to counsel by delaying his initial appearance constituted reversible error. Chavez also contended that he was denied a fair trial when, due to a change of venue, the trial court reversed an earlier order prohibiting photography of the jurors in the courtroom. Chavez argued that the State failed to prove corpus delecti[1] on the Sexual Assault charge and that the trial court erred in its consideration and application of aggravating circumstances. The Florida Supreme Court affirmed the convictions and sentence of death on 05/30/02 and issued a revised opinion on 11/21/02.

Chavez filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the United States Supreme Court on 04/23/03, which was denied on 06/23/03.

Chavez filed a 3.851 Motion in the Circuit Court on 07/09/04 and amended the motion on 05/05/05. On 01/10/07, and Evidentiary Hearing was held, and on 03/08/07, the Circuit Court denied the motion.

Chavez filed a 3.851 Motion Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court on 05/23/07, which was denied on 06/25/09. A mandate was issued on 07/22/09.

Chavez filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus in the Florida Supreme Court on 05/27/08, which was denied on 06/25/09.

Chavez filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the United States Supreme Court on 08/24/09, which was denied on 11/02/09.

Chavez filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus in the United States District Court, Southern District on 02/09/10, which was dismissed on 07/12/10.

Chavez filed a Motion for Certificate of Appealabilty in the United States District Court on 08/13/10, which was granted on 10/02/10.

Chavez filed a Habeas Appeal in the United States Circuit Court on 8/10/10. That appeal is pending.

Information 12/16/10 – updated – jjk

Chavez v. State, 832 So.2d 730 (Fla. 2002). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in a jury trial in the Circuit Court, Dade County, Marc Schumacher, J., of first-degree murder, kidnapping, and sexual battery of nine-year-old victim, and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) police had probable cause to arrest; (2) confession was voluntary despite 54 hours of police custody; (3) lack of prompt first appearance and probable cause determination did not require suppression of confession; (4) allowing photography of jurors in courtroom did not violate right to a fair trial; (5) State submitted sufficient proof of corpus delicti of sexual battery charge; (6) evidence supported finding of death penalty aggravators; and (7) death penalty was appropriate and proportional. Affirmed. Anstead, C.J., concurred in result only as to conviction, and concurred as to sentence. Shaw and Pariente, JJ., concurred in result only.

PER CURIAM.

The opinion issued in this case on May 30, 2002, is withdrawn, and the following revised opinion is substituted in its place. We have on appeal the judgment and sentence of the trial court imposing the death penalty upon Juan Carlos Chavez. We have jurisdiction. See art. V, § 3(b)(1), Fla. Const. For the reasons stated below, we affirm the judgments and sentences under review.

MATERIAL FACTS

Jimmy Ryce's Disappearance

On the afternoon of September 11, 1995, nine-year-old Samuel James (“Jimmy”) Ryce disappeared after having been dropped off from his school bus at approximately 3:07 p.m. at a bus stop near his home in the Redlands, a rural area of south Miami Dade County. An extensive and well-publicized search of the area followed, but failed to locate the child. At that time, the defendant, Juan Carlos Chavez, was living in a trailer on property owned by Susan Scheinhaus. Chavez worked as a handyman for the Scheinhaus family, and was permitted to use their Ford pickup truck to run errands or do other work for the family. As part of his duties, Chavez frequently cared for horses owned by the Scheinhaus family, but housed on property owned by David Santana, which contained an avocado grove. There was also a trailer on that property, referred to throughout Chavez's trial as the “avocado grove trailer” or the “horse-farm trailer.” FN1. The parties did not dispute that Jimmy Ryce died there, and the State introduced evidence that a spot of the child's blood was found on the floor of the trailer.

In August or September of 1995, Mrs. Scheinhaus reported to the police several times that items (including a handgun and some jewelry) were missing from her residence. Although she suspected Chavez, she lacked evidence of his culpability. She testified at trial that, in November, she had decided to obtain the evidence required to pursue her claim. With the help of a locksmith, on December 5, 1995, while Chavez was away for the day, Mrs. Scheinhaus and her son, Edward Scheinhaus (“Ed”), entered the trailer located on her property which Chavez occupied. She found the handgun—which she later identified in court as a gun she had purchased in April of 1989—in plain view on a counter opposite the trailer door. As Mrs. Scheinhaus continued to look inside the trailer, she discovered, in the closet area, a book bag which was partially open. Looking inside the bag, she saw papers and books. The work appeared to be in a child's handwriting, and she noticed the name “Jimmy Ryce.” She also observed this name on one of the books.FN2 When Mrs. Scheinhaus asked her son to look at the items, he also recognized the child's name. FN2. Jimmy Ryce's name appeared on several notebooks and a science book found in the backpack. As a result of this discovery, Mrs. Scheinhaus notified the FBI. When Chavez returned to the Scheinhaus residence at about 7:15 on the evening of December 6, armed FBI agents quickly surrounded and secured him. After being patted down, he agreed to go with Metro Dade Police officers, who were also present, to the station for questioning.

Chavez's Detention

Chavez was involved in a questioning process that was punctuated by regular refreshment, food, bathroom breaks and a rest period, and interspersed with two outings returning to the Scheinhaus and Santana properties in southern Miami Dade County. Although Chavez was first brought to the police station on the night of December 6, he did not sleep until shortly after midnight on December 7.FN3 Detective Luis Estopinan, who was bilingual, conducted most of the questioning, although other officers also participated. Various police detectives, an FBI agent, Mrs. Scheinhaus and an independent interpreter all had opportunities to observe Chavez at various times throughout this period. Chavez was consistently described as alert and articulate during this time, and no one observed police detectives mistreating Chavez in any way throughout the period of questioning. He received repeated warnings and instructions in accordance with Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966), and indicated that he fully understood them on four occasions during the period of interrogation.

FN3. The record reflects that, on the evening of December 7, Chavez commenced making a written statement, which he concluded at about 12:24 a.m. on December 8. He then received a restroom break and was offered a pillow and blanket, which he declined. Chavez returned to the interview room, where, without interruption by any interrogation, he slept or rested with the lights out until about 7:30 a.m. At that time, Chavez was awakened, provided with another restroom break, and fed breakfast before traveling to the horse farm property and the Scheinhaus property in the southern portion of Miami Dade County, accompanied by the police officers, at about 9:25 a.m.

Over the course of the interrogation, and after having been repeatedly advised of his Miranda rights and knowingly waiving them, Chavez provided several versions of his involvement in Jimmy's disappearance. As law enforcement officers engaged in a contemporaneous investigation of Chavez's changing narratives, he agreed to accompany officers on two occasions to visit the horse farm property and the Scheinhaus property, where he showed them the location of the events he had recounted had transpired. On those occasions, Chavez was asked to reveal where the boy's remains were located, to permit Jimmy's family to have closure. After the physical evidence resulting from this contemporaneous investigation totally discredited each version of events which Chavez had initially proposed, Chavez agreed to tell the truth. However, Chavez explained that, before he would disclose the location of Jimmy's remains, he wanted the officers to guarantee that he would receive the death penalty. Estopinan advised Chavez that he could not guarantee that the death penalty would be imposed. However, Chavez continued to talk, asserting that the events would not have happened had he not been sexually battered by a relative in Cuba. Estopinan told Chavez that he “felt that it was time for him to be truthful and tell us what really happened to Jimmy, and ... went back and began to ask him about Jimmy and where Jimmy was located. We wanted to find Jimmy.” A break followed this inquiry and then Chavez reiterated to Sergeant Jimenez the most recent account which he had given Estopinan. Chavez then went to the restroom for another break and, upon returning to the interview room, informed the officers that they were now going to hear the truth: “[W]hat do you want to know? I'll tell you what happened to Jimmy Ryce.” Chavez proceeded to admit to Estopinan and Jimenez that he had abducted Jimmy at gunpoint, traveled to the horse ranch, and sexually assaulted Jimmy before finally shooting him. Estopinan explained that the officers would need details from Chavez,FN4 and requested permission to take a sworn statement. Chavez agreed to continue the questioning, and Estopinan and Jimenez “began to get details” about what had happened to Jimmy Ryce. At trial, Estopinan testified regarding the final version of Chavez's statement.

FN4. Estopinan testified: “During what's called the preinterview such as in this case, what we do is we receive the information from the person we are speaking to and we document the information on to a note pad. Eventually we do our report which is consistent with the notes.”