Executed November 15, 2011 04:25 p.m. EST by Lethal Injection in Florida

41st murderer executed in U.S. in 2011

1275th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Florida in 2011

71st murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(41) |

|

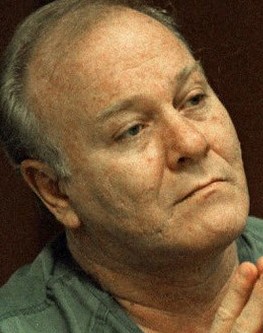

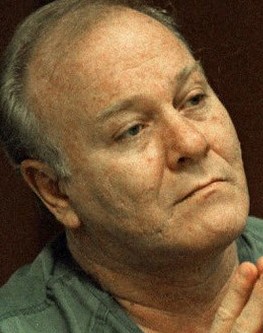

Oba Chandler W / M / 42 - 65 |

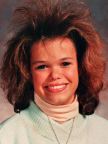

Joan "Jo" Rogers W / F / 36 Michelle Rogers W / F / 17 Christe Rogers W / F / 14 |

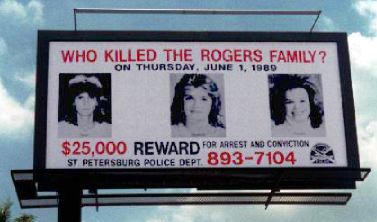

Detectives didn't crack the case for three years. Two things helped make the arrest: a tourist brochure with Chandler's handwriting was found in Rogers' car, and Chandler looked similar to a composite sketch of a suspect wanted in an earlier unsolved assault against a Canadian woman who was raped aboard a boat in Tampa Bay. Authorities took the unusual step of publicizing the handwriting on the tourist brochure, putting it on a billboard to see if anyone recognized it, under the words: "WHO KILLED THE ROGERS FAMILY?" One of Chandler's former neighbors recognized the writing and called authorities.

At Chandler's trial, prosecutors used details of the unrelated rape for which he was never tried. That Canadian woman testified Chandler took her by boat to see the sunset out on the bay and raped her. She said she believed the reason she wasn't killed was because a friend was waiting for her at the dock. Based on the similarities of the cases, prosecutors hypothesized that Rogers and her daughters were lured onto his boat with the promise of seeing the sunset and were then sexually assaulted before being murdered.

In the 17 years he was in the prison system, he never got a visit from a friend or family member.

Citations:

Chandler v. State, 702 So.2d 186 (Fla. 1997). (Direct Appeal)

Chandler v. State, 848 So.2d 1031 (Fla. 2003). (PCR)

Chandler v. McDonough, 471 F.3d 1360 (11th Cir. 2006). (Habeas)

Final / Special Meal:

Two salami sandwiches on white bread with mustard. He also asked for a peanut butter and grape jelly sandwich on white bread but ate only half of it. He ordered an iced tea, but drank coffee instead.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Florida Department of Corrections

"Oba Chandler dies for 1989 rapes, murders of mother, teen daughters," by Jamal Thalji. (11-16-11)

STARKE — The man who raped and killed a mother and her two daughters in one unfathomable night of horror 22 years ago closed his eyes and died in his sleep on Tuesday. Oba Chandler was executed by lethal injection at 4:25 p.m. for the 1989 murder of Joan Rogers and daughters Michelle and Christe. The Ohio family was visiting Florida when they were found floating in the bay, bound, tied to concrete blocks and stripped below the waist.

When the bodies of the three women were found, their mouths were taped shut but not their eyes. Their killer wanted them to watch, according to the FBI profile, so he could enjoy their terror.

An hour after his death, state officials revealed Chandler wasn't telling the truth. He had left behind a final statement.

"You are killing a innocent man today," Chandler had written on lined paper by 9 a.m.

"Bull - - - -," said Pinellas-Pasco Chief Assistant State Attorney Bruce Bartlett, who helped prosecute Chandler and witnessed his death. "A jury of 12 didn't seem to think so."

Joan "Jo" Rogers, 36, and teenagers Michelle, 17, and Christe, 14, were last seen alive on June 1, 1989. They were found in Tampa Bay three days later.

It took three years to crack the case. First their murders were linked to the rape of a 24-year-old Canadian woman two weeks before. A friendly local invited her onto his boat, then raped her. The Rogers family must have been similarly charmed, police believe.

Tampa resident Jo Ann Steffey realized that the sketch of the rape suspect matched her neighbor, Chandler. Later, his neighbors realized that handwritten directions given to the Rogers family also matched Chandler's handwriting.

But the task force investigating the murders was flooded with tips. It took more than a year before they focused on Chandler.

At his 1994 trial, the jury heard that five ship-to-shore calls were made from his boat, Gypsy 1, in the bay hours after the Rogers family was last seen. Jurors also heard that Chandler bragged of his crimes. The Canadian victim explained how Chandler charmed, then attacked her.

Chandler testified that he was innocent, that his boat had broken down that night. But a boat mechanic punctured his story.

"Chandler executed for 1989 triple murders," by Chad Smith. (Tuesday, November 15, 2011)

RAIFORD — Oba Chandler was executed by lethal injection Tuesday, his fate seemingly in stark contrast with how he ended the lives of an Ohio woman and her two teenage daughters more than 22 years ago. Chandler, 65, was pronounced dead at 4:25 p.m. in the death chamber at Florida State Prison after a lethal dose of drugs was sent through his veins.

In the summer of 1989, Joan “Jo” Rogers, 36, and her daughters, Michelle, 17, and Christe, 14, were visiting Florida for their first family vacation. On June 1, prosecutors said, they met Chandler, who invited them onto his boat for a cruise around Tampa Bay.

Three days later, their half-nude bodies were found in the water. They had been tied with rope and weighted down with concrete blocks. They had apparently been sexually assaulted before they were thrown overboard still alive.

Years earlier, it was Chandler's handwriting that helped lead to his arrest — more than three years after the murders.

Investigators made the decision to put up billboards in Tampa with a sampling of the suspect's handwriting, which was taken from directions to the boat they found in the Rogers' car.

A woman noticed the writing matched that of Oba Chandler, her former neighbor and an aluminum contractor she was already suspicious of, and called police.

Chandler was arrested on Sept. 24, 1992, and convicted on Nov. 4, 1994.

In the 17 years he was in the prison system, he never got a visit from a friend or family member, said Gretl Plessinger, a spokeswoman for the Department of Corrections. Still, the family did claim his body and will receive it later this week following a routine autopsy.

A woman who said she was Chandler's biological daughter showed up at the media staging area across from the prison on Tuesday.

The 40-year-old woman, Suzette, who said she was born Suzette Chandler in Ohio but declined to give her current last name or where she lived, said from what she had read of the case and told about her father, she considered him a “very sick, evil human being.”

She said he tried to contact her shortly after the murders in 1989, a few years after she had reached out to him after learning that he was her father.

Chandler's only supporter in the witness room was his attorney through the appeals process, Baya Harrison III.

For his last meal, served around 11 a.m., Chandler ate two salami and mustard sandwiches on white bread and half of a peanut butter and grape jelly sandwich, Plessinger said. He asked for unsweetened iced tea but did not drink it. Instead he had coffee.

The execution was scheduled to begin at 4 p.m. but it was delayed about seven minutes as officials struggled to find veins suitable for the intravenous needles, Plessinger said. Chandler took diazepam to reduce anxiety before his final moments.

Chandler closed his eyes at 4:09 as the first of three drugs — to render him unconscious — was administered and his mouth opened slightly at 4:10, his face remaining that way until he was pronounced dead 15 minutes later.

Hal Rogers, Jo Rogers' husband and the girls' father, ran a dairy farm with his wife in Wilshire, Ohio, and needed to stay home to tend to the cows when the women of the house set out south on Interstate 75 for the Sunshine State in May 1989.

The St. Petersburg Times reported last month that he has since remarried to a widow named Jolene and now raises hogs and grows corn. At that time, he wasn't sure whether he would attend Chandler's execution.

“I miss them all,” he told the newspaper. “That makes it rough on Jolene. How do you fight a dead person? But her first husband died too. She understands.”

On Tuesday, Rogers was there wearing a coat and tie, sitting in the middle of the front row in the witness room. He did not speak with reporters afterward.

Amanda “Mandi” Scarlett, Joan Rogers' niece, sat next to him during the execution and later read a statement at a news conference.

“The family of Jo, Michelle and Chris are very appreciative of everyone that has brought us to this day,” Scarlett said. “The journey has been difficult for all of us involved. We have always been grateful to those who brought us to this place, and we were grateful that they were brought back home to us. Now is the time for peace.”

"Killer of 3 faces scheduled execution in Florida," by Tamara Lush. (Associated Press 11-15-11)

STARKE, Fla. -- A man who was convicted of the 1989 killings of an Ohio woman and her two teenage daughters in Florida as they returned from a dream vacation to Disney World was executed Tuesday.

Oba Chandler, 65, was given a lethal injection and pronounced dead at 4:25 p.m. Tuesday at the Florida State Prison, Gov. Rick Scott's office said. The execution began at 4:08 p.m. and concluded without any problems.

Prison officials later released what they said was a final statement from Chandler, who had only said "No" when asked if he had any last words to speak as he awaited execution.

"Today you are killing a innocent man," the note read.

There were 21 witnesses, plus 11 members of the media in attendance. Hal Rogers, the husband and father of the victims, watched calmly from the front row. Neither Rogers nor any of the other witnesses spoke during the execution.

Mandi Scarlett, a niece of victim Joan Rogers, spoke briefly after the execution.

"Now is the time for peace," she said.

Chandler was convicted in 1994 of killing 36-year-old Joan Rogers and her daughters, Christe and Michelle, who were 14 and 17, and dumping their bound bodies in Tampa bay. The three were on their first vacation and making their way home to their small farming community of Willshire, Ohio, after their Florida trip.

Authorities concluded that the women met Chandler on June 1, 1989, when they stopped and asked him for directions to their Tampa area motel. Chandler, who had ties to Ohio, apparently sweet-talked the women into going on his boat, police said.

Once aboard, Chandler bound the victims' arms and legs, tied concrete blocks to ropes around their necks and then threw them overboard, according to detectives. Despite the concrete blocks, the bodies surfaced and were found days later, naked from the waist down.

Detectives didn't crack the case for three years. Two things helped make the arrest: a tourist brochure with Chandler's handwriting was found in Rogers' car, and Chandler looked similar to a composite sketch of a suspect wanted in an earlier unsolved assault against a Canadian woman who was raped aboard a boat in Tampa Bay.

Authorities took the unusual step of publicizing the handwriting on the tourist brochure, putting it on a billboard to see if anyone recognized it, under the words: "WHO KILLED THE ROGERS FAMILY?" One of Chandler's former neighbors recognized the writing and called authorities.

At Chandler's trial, prosecutors used details of the unrelated rape for which he was never tried. That Canadian woman testified Chandler took her by boat to see the sunset out on the bay and raped her. She said she believed the reason she wasn't killed was because a friend was waiting for her at the dock. Based on the similarities of the cases, prosecutors hypothesized that Rogers and her daughters were lured onto his boat with the promise of seeing the sunset and were then sexually assaulted before being murdered.

Chandler took the stand at trial and acknowledged to giving Rogers directions, but denied that he had anything to do with the killings.

Scott signed Chandler's death warrant on Oct. 11, the second he has signed since taking office as governor. The Florida Supreme Court affirmed a lower court decision to proceed with the lethal injection.

Since his conviction in 1994, Chandler had not received any friends or visitors.

For his last meal Tuesday, Chandler ate two salami sandwiches on white bread, half of a peanut butter sandwich and had coffee. "He's cooperative and doing what the officers tell him," Florida State Prison spokeswoman Gretl Plessinger said.

Chandler's lawyer, Baya Harrison, said that some members of Chandler's family had wanted to see him. But years ago, Chandler became angry with his family and took all of them off his visitation list, the lawyer said. According to state prison rules, once the death warrant was signed, Chandler couldn't add family back to his visitation list - the lawyer said.

"He's had problems with his family over the years," said Harrison, adding Chandler would have liked to have seen some of his relatives.

About three dozen protesters - bused in from Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church in Daytona - protested less than a half mile from the prison gates against the death penalty. They held up signs with such phrases as "Thou Shalt Not Kill" and "We Remember the Victims But Not With More Killing."

About 50 yards away, four protesters in favor of the death penalty stood by. Florida Highway Patrol officers stood watch between the two groups.

"Chandler's daughter wanted to say goodbye," by Rob Shaw. (November 27, 2011 - 5:34 PM)

TAMPA - Valerie Troxell has no idea what happened to her father's body after he was executed by the state of Florida.

"I'd at least like to know where he's buried," she said of Oba Chandler, the triple murderer who was put to death by lethal injection on Nov. 15 at Florida State Prison outside Starke. "Just to be able to say a final goodbye."

After an autopsy, Chandler's body was claimed by his son, Jeff Chandler, who lives in Pasco County, according to the Department of Corrections. Prison officials also gave Jeff Chandler family photographs that Oba Chandler had in his cell on death row.

Chandler was executed for the June 1989 murders of Joan Rogers and her two teenage daughters, whose bodies were found in Tampa Bay while they were on their first family vacation from their Ohio farm. The three were found naked from the waist down, their hands and ankles tied and a concrete block tied around their necks.

The former Tampa man maintained his innocence until the day he died, even writing a note to prison officials that they were killing an innocent man.

Troxell, who never had a relationship with her father and has only vague memories of spending time with him at an amusement park once, still believes in him.

"I believe they did execute an innocent man. I don't think one person could have pulled off such a heinous crime," she said by telephone from her home outside Cincinnati. "It would have to have been more than one person. I believe the killers are still out there.

"The forensic evidence was not there. The palm print would prove he did meet them and gave them directions, but it didn't mean he killed them," Troxell added. "I think the prosecution had a very weak case."

Chandler's palm print on a Clearwater Beach brochure and his handwritten directions on that item were integral in the state's case to convict Chandler. Prosecutors told the jury that Chandler came across the Rogers' trio when they were trying to find their hotel on the Courtney Campbell Causeway, then lured them onto a sunset cruise where he killed them.

Troxell said she fought to keep Chandler alive as the end neared for her father.

"I did everything I could to stay his execution and I got no response," she said. "I called the governor's office and he declined to take my phone call. That angered me. He was making such a big decision and wouldn't even give me the courtesy of answering my phone call."

Since the execution, the daughter said, life for her has not been easy.

"It's been horrible," she said. "I haven't been able to sleep well, I've been anxious. Everything is finalized."

Chandler never had a single visitor, other than his attorney, in all his years on death row. The only person to witness the execution on his behalf was Baya Harrison, the lawyer who fought for his life in various death appeals over the years.

"The poor guy had nobody there for him," Harrison said. "I was not about to leave him there alone."

While Harrison had said before that Chandler was resigned to his fate and was tired of living in a cramped cell, Troxell was not so sure.

"I don't think anyone wants to die. I don't think it was his wish to be put to death," she said. "I'm sure he was tired of living that existence.

"He probably felt alienated from everyone," Troxell added. "That in itself is inhumane, to keep someone in a cell 23 hours a day and not allow them to socialize. I think I would go crazy."

The daughter said while she feels pain for the loss of her father, she also worries about the suffering of Hal Rogers, who attended her father's execution.

"I can't imagine what life is like without his wife and two daughters," she said. "I pray for him every day. I can't imagine what kind of pain that must cause him.

"But I believe that Obie's innocent. He did a lot of things in his life that I am not proud of as his daughter," Troxell added. "He has a lengthy criminal record. But murder? No, I don't believe it."

The daughter said she was surprised that Chandler didn't have anything to say when afforded the opportunity for a final statement before the flow of lethal chemicals began invading his body.

"I'm really surprised he didn't tell them to kiss his behind," she said. "I probably would have."

"Florida and Ohio execute men over two triple murders," by Michael Peltier. (Tue Nov 15, 2011)

TALLAHASSEE, Fla/COLUMBUS, Ohio (Reuters) - Florida and Ohio each executed men by lethal injection on Tuesday, one for killing a mother and two daughters on vacation and another for shooting dead his three sons.

The executions brought to 41 the number of people put to death in the United States this year.

Oba Chandler, 65, was executed in Florida for the murders of Joan Rogers, 36, and her daughters Michelle, 17, and Christe, 14, who were traveling back to Ohio after a trip to Disney World in 1989.

They met Chandler in Tampa, where they stopped to ask for directions after becoming lost searching for their motel, authorities said. Chandler gave them directions to a Days Inn and then apparently offered to take them on a sunset cruise on his boat, "Gypsy One," that evening on Tampa Bay.

The mother and daughters were never seen alive again. Their three bodies -- bound, gagged and naked below the waist -- were found floating in Tampa Bay three days later.

It took investigators three years to solve the case. Local officials posted billboards in the Tampa Bay area showing the distinctive handwriting found scribbled on a tourist brochure in Rogers' car, which led to Chandler's arrest in 1992.

At trial, prosecutors said Chandler had lured the trio to his boat, raped them and dumped them into the bay with cement blocks tied around their necks to make sure they sank. Chandler testified he had given Rogers directions but said he was out fishing alone the night of the murders.

A Canadian tourist testified that she had been raped by Chandler, an aluminum contractor by trade, under similar circumstances a few weeks before the murders.

Chandler was convicted in 1994 and sentenced to death on three counts of first-degree murder. He was pronounced dead on Tuesday at 4:25 p.m. local time at Florida State Prison near Starke, said Amy Graham, spokeswoman for Florida Governor Rick Scott.

Chandler's last meal consisted of two salami sandwiches on white bread and half a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. He made no final statement, Graham said.

Florida Commission on Capital Cases

CHANDLER, Oba (W/M)

Sixth Judicial Circuit, Pinellas County, Case #92-17438

Date of Offense: 06/01/89

Circumstances of Offense:

Oba Chandler was convicted and sentenced to death for the murders of Joan Rogers and her two daughters, Michelle and Christe, on 06/01/89.

Joan Rogers and her daughters were vacationing in Tampa from Ohio and checked into their hotel on 06/01/89. Housekeeping staff noticed that their room remained uninhabited for over week, at which point, they contacted the manager, who then contacted police. Upon investigation, the Rogers’ car was found abandoned beside a boat ramp off the Courtney Campbell Causeway. Inside the car they found a brochure with directions on it, parts of which were written in Oba Chandler’s handwriting. Chandler’s fingerprints were also lifted from the brochure.

The bodies of all three women were found tied and weighted in Tampa Bay on 06/04/89. Each woman was naked from the waist down, arms and legs bound, and a cinder block was tied by a rope around their necks. Medical examiners determined the cause of death of all three women to be asphyxiation from the ropes around their necks, or from drowning.

Investigation revealed similarities between the Rogers’ murders and the rape of a woman in a nearby area. From information given by Judy Blair, the victim of the rape, a composite drawing was made of the suspect and printed in the local paper, along with the stories of the two crimes. After seeing the article, Chandler fled the area and stayed with relatives. He admitted to them that the police were searching for him in connection with the rape/murder investigation.

At trial, Judy Blair testified that when she first met Chandler he offered to take her on a sunset cruise on his boat. Not fearing for her safety in the least, Blair accompanied Chandler on a ride through Tampa Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. While at sea, Chandler raped Blair. Blair testified that she believed he would have killed her had it not been for the fact that a friend was waiting for her back at the dock. The State used this incident to hypothesize how Chandler lured the Rogers family with the offer of a cruise on his boat before he killed them. Chandler was not arrested or charged with the murders until September 1992.

Prior Incarceration History in the State of Florida:

Offense Date: 02/02/1976

Offense: ROBBERY W/FIREARM OR D/WEAPON

Sentence Date: 01/12/1977

County: VOLUSIA

Case #

Sentence Length: 10Y 0M 0D

Offense Date: 03/03/1991

Offense: POSS.FIREARM BY FELON

Sentence Date: 10/13/1994

County: VOLUSIA

Case #: 9333980

Sentence Length: 10Y 0M 0D

Offense Date: 09/11/1991

Offense: ROBBERY W/FIREARM OR D/WEAPON

Sentence Date: 07/23/1993

County: PINELLAS

Case #: 9215615

Sentence Length: 15Y 0M 0D

Trial Summary:

11/10/92 Defendant indicted on: Count I: First-Degree Murder (Joan Rogers); Count II: First-Degree Murder (Michelle Rogers); Count III: First-Degree Murder (Christe Rogers).

11/16/92 Defendant entered a plea of not guilty.

09/29/94 The jury found the defendant guilty on all counts.

09/30/94 The jury, by a 12 to 0 majority, voted for death penalty on all three convictions.

11/04/94 The defendant was sentenced as follows:Count I: First-Degree Murder (Joan Rogers)-DEATH; Count II: First-Degree Murder (Michelle Rogers)-DEATH; Count III: First-Degree Murder (Christe Rogers)-DEATH.

Appeal Summary:

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal

12/05/94 Appeal filed.

U.S. Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

02/20/98 Petition filed.

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

06/22/98 Motion filed.

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

07/05/01 Appeal filed.

06/27/03 Petition filed.

U.S. Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus Appeal

02/13/06 Appeal filed.

U.S. Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

03/15/07 Petition filed.

Factors Contributing to the Delay in the Imposition of the Sentence:

Chandler’s Direct Appeal and 3.850 Motion each took approximately three years to complete. During the progression of the 3.850 Motion, CCRC-M, Chandler’s defense counsel, asked to be removed from the case citing a heavy caseload. After that, Baya Harrison, Esq. took over Chandler’s defense representation on 08/27/99, was granted an extension in filing Chandler’s amended 3.850 Motion on 11/01/99 and, in turn, filed the amended 3.850 Motion on 04/30/00.

Case Information:

Chandler filed a Direct Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court on 12/05/94. In that appeal, he argued that admitting evidence regarding the sexual battery of Judy Blair unfairly prejudiced his case. Chandler also claimed that the trial court erred in repeatedly requiring him to invoke his Fifth Amendment right to remain silent, and in admitting statements made by his daughter Kristal Mays. Regarding the penalty phase, Chandler contended that the court erred in accepting his waiver of the presentation of mitigating evidence, and in the application of aggravating and mitigating circumstances. The Florida Supreme Court affirmed the convictions and sentences of death on 10/16/97.

Chandler then filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the U.S. Supreme Court, which was denied on 04/20/98.

Next, Chandler filed a 3.850 Motion in the State Circuit Court, which was denied on 06/27/01. He promptly filed an appeal of that decision in the Florida Supreme Court on 07/05/01, which was affirmed on 04/17/03. Chandler’s Motion for Rehearing was denied on 6/24/03.

On 06/27/03, Chandler filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus in the U.S. District Court that was denied on 02/08/06.

Chandler filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus in the U.S. Court of Appeals on 02/13/06, and on 12/20/06, the USCA affirmed the denial of the petition. A Mandate was issued on 01/19/07.

Chandler filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the U.S. Supreme Court on 03/15/07 that was denied on 05/14/07.

Oba Chandler (October 11, 1946 – November 15, 2011) was an American convicted rapist and murderer who was put to death via lethal injection for the June 1989 triple murders of a woman and her two daughters whose bodies were found in Tampa Bay, Florida.[1] All three were discovered floating with their hands and feet bound, concrete blocks tied to their necks and duct tape over their mouths. Autopsies indicated the women had been thrown into the water one by one while still alive.[2]

The case became high-profile in 1992 when police posted billboards with blowups of an unknown suspect's handwriting samples found on a pamphlet in the victims' car, leading to the identification of the killer when Chandler's neighbor recognized the writing. Billboards had not been used by police before, and became useful tools in later searches for missing people.[3]

Prior to his arrest, Chandler worked as an aluminum building contractor. He testified in his own defense against the advice of his attorneys and admitted that he had met the Ohio women, giving them directions, but claimed he never saw them again aside from newspaper coverage and the billboards set up by investigators.[4] Police originally theorized that there were two men involved in the murders of the Rogers women; however, this was discounted once Chandler was arrested.[5] Following his conviction, Chandler was incarcerated at Florida State Prison.

On October 10, 2011, Florida Governor Rick Scott signed a death warrant for Chandler. His execution was set for November 15, 2011, at 4:00 pm.[6] Chandler was executed with a lethal injection and pronounced dead just after 4:25 pm.[7]

Background: Chandler was born to Oba Chandler Sr. and Margaret Johnson and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, approximately 100 miles from where the Rogers family was living. Chandler was the fourth of five children.[8] When Chandler was only 10 years old, his father hanged himself in the basement of the family's apartment.[8] His father's death in June 1957 affected Chandler so much that he reportedly jumped into the open grave at the funeral as the gravediggers were covering the coffin with dirt.[9]

Chandler fathered eight children, the youngest born in February 1989.[8] Between May and September 1991, at the same time that Tampa police investigated the Rogers family triple murder, Chandler was an informant for the U.S. Customs Tampa office.[10]

Earlier crimes and incidents: Chandler was stealing cars by age 14 and was arrested 20 times while he was a juvenile. As an adult he was charged with a long list of crimes, including possession of counterfeit money, loitering and prowling, burglary, kidnapping and armed robbery.[11]

He was also accused of masturbating while peering inside a woman's window, and on another occasion of receiving 21 wigs stolen from a beauty parlor.[8] In one incident, Chandler and an accomplice broke into the home of a Florida couple and held them at gunpoint while robbing them. Chandler told his accomplice to tie up the man with speaker wire and then took the woman into the bedroom, where he made her strip to her underwear, tied her up and rubbed the barrel of his revolver across her stomach.[9]

Rogers' murders: On May 26, 1989, Joan "Jo" Rogers, 36, and her daughters – Michelle, 17, and Christe, 14 – left their family dairy farm in Willshire, Ohio for a vacation in Florida. [12] They had never before left their home state. On June 1, authorities believe, the women became lost while looking for their hotel. They encountered Chandler, who gave them directions and offered to meet them again later to take them on a sunset cruise of Tampa Bay.[13] It is known that the Rogers women left Orlando that morning around 9 a.m.[14] and checked into the Days Inn on Route 60 at 12:30 p.m. Snapshots recovered from a camera left in their car showed the last picture of Michelle while she was alive, and even the sun setting on the same bay where their lives later ended.[15] They were last seen alive at the hotel restaurant around 7:30 p.m. It is believed they boarded Chandler's boat at the dock on the Courtney Campbell Causeway (part of Route 60) between 8:30 and 9:00 p.m., and that they were dead by 3 a.m. Chandler could also have used the fact that he was born in Ohio to lure them into feeling more connected with him.[16] It is also believed that he knew that the women were not from Florida, as he recognized the Ohio car plates since he himself was originally from Cincinnati.[17]

Sunshine Skyway over Tampa Bay where the first body was found on June 4, 1989: The women's bodies were found floating in Tampa Bay on June 4, 1989, with bound hands and feet, concrete blocks tied to their necks and duct tape over their mouths. The first body was found floating when a sailboat, on its way home to Tampa after a trip to Key West, had just crossed under the Sunshine Skyway when several people on board saw an object in the water. This was identified as a dead female.[18] The second body was floating to the north of where the first had been sighted. It was 2 miles off The Pier in St. Petersburg. While the Coast Guard went to recover the second body, a call came in of yet a third female, seen floating only a couple of hundred yards to the east. Like the first two victims found, this body was face down, bound, with a rope around the neck and naked below the waist.

Autopsies indicated the three women had been thrown into the water while still alive.[19] This was bolstered by water found in their lungs and the fact that Michelle had freed one arm from her bonds before succumbing. Michelle was thereby identified as the second victim found in Tampa Bay and recovered. The partially-dressed bodies of all three women indicated that the underlying crime was sexual assault.[19] The blocks were tied around each of their necks to make sure they died from either suffocation or drowning, and to make sure the bodies were never found. However, the bodies ended up being found when they bloated due to decomposition and floated to the surface.[19]

InvestigationThe women were not positively identified until a week after their bodies' discovery, by which time they had been reported missing back home in Ohio by the husband and father, Hal Rogers.[20] A housekeeper at the Days Inn noted on June 8 that nothing in the room had been disturbed, and that beds had not been slept in. She contacted the general manager, who then contacted the police.[19] Fingerprint matches to the bodies were made from those found in the room. Final confirmation of their identification came from dental records sent from the Rogers' dentist in Ohio. Marine researchers at Florida International University studied the currents and patterns, and confirmed that the women were tossed from a boat and not from a bridge or dry land, and that it had happened anywhere from two to five days before they were found. This was confirmed when the Rogers car, a 1984 Oldsmobile Calais with Ohio license plates, was found at the boat dock on the Courtney Campbell Causeway.[20]

Facts pointing to Chandler and arrest: The case remained unsolved and cold for over three years, partly due to the volume of tips pouring in to the police who investigated the crime.[21] Chandler was not arrested for the murders until September 24, 1992.[18] [21] His handwritten directions on a brochure found in the Rogers vehicle, along with a description of his boat written by Jo Rogers on the brochure, were the primary clues that led to his being named a suspect. Also, authorities had posted the handwriting from the brochure on billboards, which was historic as it was used for the first time in an attempt to find an unknown killer. This led to a tip from a former neighbor who was able to provide a copy of a work order that Chandler had written. A handwriting analysis conclusively matched the two.[21] Another neighbor, as well as one of the secretaries on the investigative task force, also thought that Chandler resembled the composite sketch of the suspect in a seemingly related rape case (see next paragraph). A palmprint from the brochure was also matched to Chandler. Moreover, Chandler had sold his boat and left town with his family soon after the billboards appeared all over the Tampa Bay area.[22] In 1990, when the TV show Unsolved Mysteries was about to report on the deaths of the Rogers family, Chandler and his then-wife moved from their home on Dalton Avenue in Tampa to Port Orange near Daytona Beach. This is believed to be because Chandler felt more worried about being caught because of the upcoming television show about his crime.[21]

Second suspectInvestigators originally theorized that two men were involved in the murders of the Rogers women. This theory was reflected in a 1990 episode of the American crime television show Unsolved Mysteries, in which a reenactment of the crime depicted two men leaving the dock with the three women on board a boat.[23] This theory, however, was dismissed when Chandler was arrested. Other than a claim by a former prison cellmate that Chandler has said there was another man involved – whom the cellmate claimed to know the identity of but would not name – no evidence has ever surfaced regarding the involvement of anyone other than Chandler. The second-suspect theory is belied by Chandler's approach of two Canadian women – that he had the willingness to approach more than one potential target by himself.[24]

John Rogers, Hal Rogers's brother, was also seriously considered a suspect even though he was in state prison at the time. John Rogers was in fact serving a prison term for the rape of Hal's daughter Michelle.[18] Soon investigators established that John did not have the connections in prison to have done the murders via a hitman or friend. John Rogers was released from prison in 2004 and has had no further contact with his brother Hal since.[24]

While living in a trailer in Willshire, John had allegedly lured two teenage girls there and sexually abused them. Subsequent police investigation turned up evidence indicating that he had also done the same to Michelle. This caused a major rift in the family and may have played an indirect part in the eventual murders. The idea that he may have planned the crime was bolstered by the fact that his and Hal's parents had property near Tampa, and that he had visited the area a month before the murders. However, he was a general loner with little close ties to even his own family, let alone friends, so such a plan, if there were one, would have been beyond character for him. For this, and the simple reason that he did not know when his sister-in-law and nieces would be there, he was dismissed as a suspect.[24]

Hal Rogers was also considered a suspect because he had posted bail for his brother after he knew of his abuse of Michelle.[25] Hal Rogers said later that he had promised the family to make bail and would not go back on his promise. Investigators from Florida and Ohio also found out that Hal Rogers had withdrawn $7,000 from his bank at the time of the disappearance.[24] When questioned about it, he showed investigators a satchel with most of the money in it. He planned on using it to go and search for his wife and daughters himself before he was notified of their deaths. Also, subsequent investigation conclusively proved he had never left Ohio during that time period.[23] The rape and the hype around Michelle Rogers by people in the neighborhood and media was one of the reasons why the Florida trip was taken, so Michelle, her sister and her mother could get some distance from the incident.[25]

Trial: Chandler's testimonyAt his trial in a Clearwater, Florida courtroom, Chandler admitted meeting the Rogers women and giving them directions, but claimed he never saw them again except in the newspaper and on billboards.[26] Yet he never came forward to tell authorities that he had seen the women.[2] He acknowledged he was on Tampa Bay that night – a fact he could not deny since the police had evidence of three ship-to-shore phone calls made from his boat to his home during the time frame of the murders – but claimed he was fishing alone. He explained that he returned home late because his engine would not start, which he attributed to a gas line leak he claimed to have found near dawn.[26] He claimed he had called the Coast Guard and Florida Marine Patrol, but they were busy elsewhere.[2] Finally, he claimed he flagged down a Coast Guard patrol boat, but they were busy and promised to send help. Then he claimed to have fixed the line with duct tape, which allowed him to make it back safely to shore.[27] His testimony was quickly refuted by the Pinellas County Prosecutor, Douglas Crow, who verbally sparred with Chandler to demonstrate that he had lied about everything. All Chandler could muster in response to the prosecutor's repeated questions was, "I don't remember."[26]

This defense won him few sympathizers on a jury that quickly saw through his façade and the inconsistencies in his statements. Moreover, there were no records of distress calls from Chandler that night to either the Coast Guard or the Marine Patrol, nor were there any Coast Guard boats on the bay the following morning to help him.[18] A boat mechanic testified for the prosecution that Chandler's explanation for repairing the boat's alleged gas leak could not have happened as he had portrayed it. Chandler's boat, a Bayliner, had a distinctive engine in which the fuel lines were directed upward.[26] A leak would have sprayed fuel into the air, not into the boat, and the corrosive gasoline would have eaten away the adhesive properties of the duct tape Chandler claimed to use to repair the purported leak.[18]

WitnessesAnother lead was that on May 15, 1989—two weeks prior to the Rogers murders—Chandler lured Canadian tourist Judy Blair onto his boat in nearby Madeira Beach, raped her, then dropped her off back on land. Blair made her way back to her hotel room where her friend Barbara Mottram was waiting.[28] He was not charged or tried for this crime.[28] It is thought he did not murder her because Barbara refused his offer to join them on the boat, a decision which more than likely saved both their lives. As a result, Judy Blair testified during his trial for the murders to establish his pattern of attack and the similarities between the two crimes. Blair testified that on May 14, Chandler gave his name as Dave Posner or Posno when the three first met at a convenience store in Tampa.[28] Presumably he gave the same alias to the Rogerses. He told Blair and Mottram he was in the aluminum contracting business, which helped lead investigators to him, as well as the naming of the investigation to capture him: Operation Tin Man. The description that Judy gave was also posted on the billboards along with the handwriting samples.

Additionally, a former employee of Chandler's testified that Chandler bragged of dating three women that night on the bay, and that the next morning he arrived and delivered materials for a job by boat and immediately set out again – presumably to make sure his victims were dead. In an attempt to establish Chandler's whereabouts on the night of the murders, investigators found phone records of several radio marine telephone calls made from his boat to his home between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. These likely were an attempt to explain to his wife his absence[29] as well as to provide himself with an alibi for his whereabouts at the time of the murders.[8] Also, Chandler's own daughter Kristal May Sue testified against her father, saying that he talked about killing the three women and that he was afraid of going back to Tampa.[30] A maid who worked at the motel where the Rogers women stayed testified that she walked past Oba Chandler as she was going to the Rogerses' room for room service on June 1, implying that it seemed as if Chandler had just left the women's hotel room at around 12:30 that afternoon. The maid said she didn't realize the importance of this sighting until Chandler's arrest in 1992, although the sighting has never been confirmed.[28]

Hal Rogers and Michelle's boyfriend also took the stand during trial.[30] Hal identified the women and talked about his emotions on June 1. The boyfriend told about a phone conversation with Michelle.[29]

Sentence and aftermath: Jo, Michelle and Christe Rogers were buried in their hometown on June 13, 1989, after a funeral service at the Zion Lutheran Church. About 300 people among them family and friends of the victims attended the service.[31][32] Because of the huge media interest for the case at the time, numerous police officers were present to keep all news media and crews out of the church during the funeral service.[32]

Chandler was tried and found guilty of the murders, and was sentenced to death on November 4, 1994.[33][34][35] After sentencing, the juror forewoman commented regarding the death sentence that, "They need to do this swiftly. The man is a mutation of a human being and he needs to be destroyed."

Chandler remained on Florida's Death Row, maintained his innocence, and continued to pursue legal appeals.[36] He admitted the Madeira Beach incident but claims the sex was consensual, and that the victim had changed her mind during the act – which, in his words, was not possible for him to do. Chandler was never prosecuted in the rape of Judy Blair, since he had already been sentenced to death for the Rogers family murders, and prosecutors did not want to subject Blair to the emotional trauma of a rape trial.[33] He continued to claim that he never met the Rogers women after that morning when he gave them directions.

Chandler served his sentence at Union Correctional Institution.[37] Shortly after the trial and conviction, his wife Debra Chandler filed for divorce, and the marriage was formally dissolved a year later. Chandler was no longer allowed to see his daughter Whitney, and in accordance with his ex-wife's wishes, he was not allowed to see current photos of Whitney.[38]

In July 2008, it was revealed that Chandler was on Florida's shortlist of executions.[39] Profiling experts believe that Chandler may have killed previously, based on the speculation that a first-time killer would not be experienced or bold enough to abduct and kill three women at once. Chandler remains a suspect in a 1982 murder of a woman found floating off Anna Maria Island.[40] However, Chandler was never charged with other murders. Chandler received an Institutional Adjustment disciplinary report on December 15, 2001, for disobeying orders in prison.[5] All of Chandler's appeals since his 1994 conviction were denied, the last one in May 2007.[41] After his conviction, Chandler was named by media as one of Florida's most notorious criminals.[42] Chandler said that his last words before his execution would be "Kiss my rosy red ass".[43]

In May 2011, comparison was drawn between the murder case and upcoming trial of Casey Anthony and Chandler's case and trial in 1994, as in both cases the heightened media attention forced the jurors to be selected from outside the county of the committed crime.[44] One of the jurors in Chandler's 1994 trial identified as Roseann Welton also commented in an interview that, "The people that he murdered did not have a choice of when they were going to die. He (Chandler) should have had the death penalty by now. He scared some of the jurors when he would sit there and stare at you and have that stupid grin on his face. He would make your skin crawl."[45]

Execution: On October 10, 2011, Florida Governor Rick Scott signed a death warrant for Chandler. His execution was set for November 15, 2011, at 4:00 pm. [46] The death warrant was signed the day before Chandler's 65th birthday. Chandler's lawyer, Baya Harrison, said that Chandler asked him not to file any frivolous appeals to keep him alive. "He is not putting a lot of pressure on me to go running around at the end to find some magic way out," said Harrison. "He is not going to make a scene. He's not going to bemoan the legal system. What he has told me is this: if there is some legal way that I can find to try to prevent him from being executed, he would like me to do what I reasonably can."[47] Harrison also said that Chandler suffered from high-blood pressure and coronary artery disease and had problems with his kidneys and with arthritis.[48]

On October 12, 2011, Harrison said that although he was preparing to file a motion regarding the violation of his client's Fifth and 14th Amendment rights in the case, he was unsure that Chandler was willing to make the trip to Clearwater for the court hearing or would even agree to the filing of the motion. "He hates coming down to Clearwater. He doesn't like the ride and he's not well," Harrison said. "He doesn't like to come out of his cell," added the attorney. "He doesn't like to be disturbed."[49]

On October 18, 2011, Harrison filed a motion against the execution on the grounds that that the way Florida imposes the death penalty is unconstitutional.[50] According to the filed motion, a jury makes a recommendation on life or death, but Florida law gives the judge the final say. [51] A hearing on Chandler's motion was set for October 21 at 1:00 PM; Chandler did not attend the hearing in Clearwater, Florida.[52] On October 24 Chandler's appeal was rejected because he had already filed an appeal to the Florida Supreme Court prior to the decision.[53] This appeal was heard in a court in Tallahassee at 9:00 AM on November 9, 2011. The Florida Supreme Court has already upheld Oba Chandler's death sentence twice, once in 1997 and again in 2003.[54]

On November 15, Chandler had chosen a last meal consisting of two salami sandwiches on white bread, one peanut butter sandwich on white bread and iced tea.[55]

The execution process started at 4:08 p.m and at approximately 4:25 pm Chandler was pronounced dead after receiving a lethal injection at the Florida State Prison in Raiford, Florida.[56] Chandler declined to make a last statement before being executed.[57] Hal Rogers, the husband and father of the victims, attended the execution.[58] Former St. Petersburg homicide detective Cindra Leedy who investigated the case said in a press conference that "I'm glad there's finally an end to this. He doesn't deserve to live, he needs to die".[59]

Governor Rick Scott commented on his decision to sign the death warrant. "He (Chandler) killed three women, so I looked through different cases, and it made sense to do that one. There's never one thing. It was the right case."[60]

Media concerning the caseThe Discovery Channel devoted a one-hour episode concerning the murder of the Rogers family, "The Tin Man", on their series Scene of the Crime.[61] The case was also one of three in an episode of the Discovery series Forensic Detectives. The former focused on the underlying events of the crimes, while the latter focused on forensic evidence. In 1997, a series of articles entitled "Angels & Demons" written by Thomas French was published in the St. Petersburg Times newspaper.[62] The series told the story of the murders, the capture and conviction of Chandler and the impact of the crimes on the Rogers' family and community in Ohio, most notably their husband and father, Hal Rogers.

The articles won a 1998 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing.[9] Death Cruise, by author Don Davis, also covered the case. The Rogers murders were featured in an episode of Unsolved Mysteries in 1990, where it was speculated that there were two attackers.[9] The book Bodies in the Bay, by Mason Ramsey, is a fictionalized adaptation (copyrighted in 1997, published in 2000).[9] The case was also featured in a 1999 episode of Cold Case Files on A&E entitled Bodies in the Bay, which also focused on the evidence, but did not delve too deeply into the background of the murders.[63] In 1995 Oba Chandler, some part of his family and also Hal Rogers appeared in a special episode of the Maury Povich Show featuring on the case. Chandler commented on the case via satellite link.[12] Chandler's case was also brought up in a full-hour episode of "Crime Stories".[63] The case was also shown on an episode of Forensic Files entitled "Water Logged" in December 2010.

References

On Sunday, June 4, 1989 at approximately 9:30 a.m. boaters discovered three decomposed female bodies floating in South Tampa Bay. The bodies were later identified as Mrs. Joan Rogers and her daughters, Michelle and Christe. At the time of their deaths in 1989, Joan was 36, Michelle 17 and Christe was 14.

Dr. Edward Corcoran, an Associate Medical Examiner, performed autopsies on all three women on June 4 and determined that the cause of death to each was asphyxiation caused either by strangulation from the ropes tied around their necks or by drowning. Dr. Corcoran estimated that the women had died sometime between the evening of June 1 and the morning of June 2, 1989. He described the bodies as being bloated and decomposed. Each was nude from the waist down. There was duct tape on the face or the head of Christe and Michelle. Christe and Joan's hands were each tied behind their backs with clothesline-type rope. Michelle's right hand had clothesline-type rope around the wrist but the left hand was free with only a loop of rope. Michelle's ankles were bound with clothesline-type rope. Joan and Michelle each had a yellow nylon rope around their neck which was attached to a concrete block. The concrete block around 1 Joan's neck had three holes in it. The object tied to the yellow nylon rope around Christe's neck had been cut. Christe and Joan's ankles were each tied together with yellow nylon rope. There were no fractures of the hyoid bones. Besides ligature marks and discoloration behind the upper esophagus and darkening and hemorrhaging in the neck tissues of each woman, no other injuries were determined. Dr. Corcoran looked for and did not find any genital injuries. He did not look for semen nor did he expect to find any as semen would have decomposed or been washed away by the action of the water. From the contents of Joan Rogers' stomach, Dr. Corcoran was able to estimate that she last ate four to eight hours prior to her death.

Dr. Bernard Ross, an expert regarding the characteristics of water movement in Tampa Bay, testified that all three of the bodies were dumped in Tampa Bay at the same location. Based on his study, Dr. Ross opined that none of the bodies could have been thrown from a land mass such as Gandy Bridge or Howard Frankland Bridge.

At the time of their deaths, the Rogers were vacationing in Florida. The evidence showed that on Thursday, June 1 at 9:34 a.m. the Rogers checked out of the Gateway Inn in Orlando and went to Tampa, They checked into the Days Inn in Tampa shortly after the noon hour on June 1, 1989. Phone records from the hotel show that two calls made from the Rogers' room on June 1. One was placed at 12:37 pm for nine minutes and another call was placed locally in Tampa at 12:57 pm for less than a minute. Harold Malloy, a guest at the Days Inn, saw the Rogers in the hotel's restaurant on June 1, between 7:00 and 7:30 p.m. The Rogers left the restaurant at about 7:30 or 7:35 p.m. The general manager of the Days Inn, Rocky Point on the Courtney Campbell Causeway was alerted by housekeeping on June 8 that the Rogers' room did not appear to have been inhabited for a few days. After an inspection of the premises, he contacted law enforcement who came out, secured the scene and obtained records from the hotel regarding the occupants.

Officers identified numerous personal articles, clothing, suitcases and papers belonging to the occupants. There were canisters of film which had been exposed. These were developed and the last three pictures on the last roll of film showed the Days Inn Hotel, Room 251 and one of Michelle standing on the balcony of the hotel. Dr. Kendal Carder, a professor of oceanography at the University of South Florida opined at trial that the photograph of Michelle was taken sometime between 6:20 p.m. and 8:20 p.m. on June 1, 1989. Neither the camera nor the clothing depicted in the picture of Michelle was found in the victims' vehicle or among the evidence seized from Room 251 of the Days Inn. The police found the Rogers' locked car parked at a boat ramp on the causeway. There was sand wedged around the tires of the vehicle indicating it had been there for some time. Detectives later found a set of car keys belonging to the victims' car in a purse known to belong to Michelle Rogers in the motel room. A search of the vehicle revealed several exhibits, including a piece of Days Inn, Rocky Point stationery; an index card with directions to Gateway Inn, Orlando; notebook paper with personal notes; a key to Days Inn Room 251; a Clearwater Beach brochure; a Hampton Inn coupon; a Jacksonville Zoo receipt and a road atlas.

FBI Agent James Henry Mathis determined that a note handwritten on Days Inn stationery found in the victims' car was written by Joan Rogers. The note read, "Turn right. West W on 60, two and one-half miles before the bridge on the right side at light, blue w/wht." Theresa Stubbs, an examiner of questioned documents for the FDLE at the Tampa Regional Crime Laboratory, examined the handwriting on the Clearwater Beach brochure and identified Oba Chandler as the writer. From her analysis, Ms. Stubbs determined that the "Boy Scout, Columbus" portion of the writing on the brochure may have been written by Joan Rogers.

Rollins Cooper worked as a subcontractor for Oba Chandler in the spring of 1989 for 3-6 months. He testified that on June, 1,1989, between eleven and twelve a.m. Chandler brought him some screen. Cooper asked Chandler why he was in such a big hurry and Chandler told him he had a date with three women. Cooper met Chandler the next morning at 7:05 a.m. Cooper thought Chandler was kind of grubby. When Cooper asked him why he looked like that he said that he had been out on his boat all night.

Oba had a place next to his house where the scrap aluminum from the different jobs would be left. There were also some eight-by-sixteen building blocks laying there and a boat trailer. The state also presented the testimony of Judy Blair and her companion Barbara Mottram concerning Chandler's sexual battery of Judy Blair in Madeira Beach. Judy Blair testified that she and Barbara were in Florida on vacation from Ontario, Canada, when they met Chandler at a convenience store. Chandler told them that he knew the area and that he worked in the area; that it was a highcrime area and that two young girls should be very careful. He said his name was "Dave" and he worked in the aluminum-siding business. He said that he had a boat and because he knew the area so well, he would take them out on the boat and show them the area from the water. After they told him they were from Canada, he told them he was from upstate New York. His demeanor was very friendly, very warm. They made plans for the next day and what time he would pick them up. Chandler invited both Judy and Barbara out on the boat. The next morning Barbara insisted that she did not want to go and Judy told her that the plans were made and that she had no way to get hold of the person. Chandler had told Judy that he would be coming from approximately two hours away. She decided to go even though Barbara would not be going. Wearing a white T-shirt, a pair of cotton shorts, sneakers and a bathing suit underneath, Judy met Chandler at 10:30 a.m. He was in an older blue and white boat. The interior bottom was white or off-white. There was a space under the bow; a storage area with equipment. She saw white ropes in the compartment down below. Judy did not remember seeing any concrete blocks on the boat. When Judy explained that Barbara wasn't coming, Chandler seemed disappointed. He pulled some duct tape from the storage area and taped the steering wheel. He told Judy that he kept his boat lifted up out of the water on davits.

At approximately 4:30 he returned Judy to the docks. He said that he had some difficulty with his boat and he had to attend to it. He told her to go home and get dinner, her camera so she could take pictures of the sunset and get Barbara. He specifically asked Judy to get Barbara. They were to meet back later at the same dock after dinner. Judy could not convince Barbara to go and Judy went back to the dock by herself. She took her camera with her. The man was already at the dock. He seemed "ticked off" that Barbara did not come. It was still daylight when they got on the boat and went under the bridge into the gulf. They drove through the gulf and stopped to take pictures of the sunset. Dave was in some of the pictures and Judy was in some of the pictures. They started to fish and Judy expressed concern that it was getting dark and she needed to get back; that people were waiting for her back on land. He started complimenting her and asked for her to give him a hug, She thanked him for the compliments and declined to give him a hug. He pulled Judy towards him and started touching her arms and around her body. He told her he was going to have sex with her. She told him "no" and asked him to take her back home. She started screaming and he said, "You think somebody is going to hear you? " Judy was panicky and was pleading with him to take her back.

At one point he started the boat; she thought to return to the shore. He took her further out in the water instead. Chandler stopped the boat and told her, "You're going to have sex with me. There's no way around it. What are you going to do, jump over the side of the boat?" Judy continually screamed and tried to get away from him. He sat on the passenger seat and pulled his pants down and took the back of Judy's head and made her perform fellatio on him. He put a towel down on the bottom of the boat and forcibly put her down. Judy was screaming and crying and he told her to "Shut up. Shut up. If you don't shut the fuck up, I'm going to tape your mouth. Do you want me to tape your mouth?" He pulled down the bottom half of what she was wearing and said, "You're going to have sex with me." Judy was kicking and screaming and crying and he was saying, "I'll tape your mouth. I'll tape your mouth." At that point she became fairly quiet. He also made reference to the fact that, "Is sex really something to lose your life over?" He started fondling her vaginal area. She was menstruating and he found the tampon and he pulled it out. At some point Chandler rolled Judy over onto her knees and attempted to penetrate her anally. She pleaded with him not to do that; that she had rectal cancer. He turned her over and penetrated her vaginally. He ejaculated, immediately pulled out, pulled his pants back up. He threw her a thermos bottle filled with water and told her to wash herself out. He took the camera, ripped the film out and threw it overboard. Then he wiped down the camera. He told Judy, "I know you're going to report this, but please give me a chance to go home to tell my little old mother." He took her back to shore. He dropped her off on the other shore of the channel from Don's Dock. Judy walked home.

She did not say anything to her mother or aunt or uncle when she got back. She just wanted to have a bath and go to bed. After her mother and aunt and uncle left the condominium, Judy told Barbara what happened. She ultimately reported it to the police later that evening of the 16th. Judy gave a description of the clothing "Dave" was wearing the evening he assaulted her and identified it at trial. Barbara confirmed Judy's testimony concerning how they met Chandler, that he was driving a black or very dark vehicle which resembled a Jeep Cherokee, that he was from upstate New York but resided in Florida and that he had to travel a little bit of a ways to get to Madeira Beach. Barbara confirmed that Judy came back to retrieve Barbara to go out on the boat. Judy said that both she and "Dave" (Chandler) wanted her to go on the sunset cruise. Barbara declined this second invitation. Judy took a camera with her. The next morning Judy related to Barbara what had happened to her the night before on the boat. Barbara testified that Judy was devastated. She was in shock. She was in tears and sobbing all day long. Barbara picked Oba Chandler's photograph out of a photo pack, identified him in a lineup of people and in the courtroom. Barbara also identified a photograph of Chandler's car and a photograph of Chandler as being more consistent with the what he looked like in 1989 than in the courtroom.

Detective James Kappell, of the St. Petersburg Police Department testified that in September, 1989 he became aware that a rape had occurred in Madeira Beach involving two Canadian tourists. Kappell traveled to Canada to interview Judy Blair and Barbara Mottram. Kappell obtained a composite drawing of "Dave" . The description of the suspect's vehicle, boat and his composite was released to the press and seen by Chandler's neighbor Joann Steffey. Ms. Steffey thought of Chandler when she saw the composite. She was aware that Chandler had a boat. It was blue and white with a blue top cover. Chandler had a black four-wheel drive vehicle.

In May, 1992 Ms. Steffey observed another newspaper article talking about the rape and the Rogers' homicides. The article contained a picture of the handwriting involved on a brochure. Upon seeing this second newspaper article, Ms. Steffey obtained a sample of Chandler's handwriting and concluded that it was the same. Ms. Steffey called the Task Force in St. Petersburg to notify them of her belief. Her neighbor FAX'd the handwriting sample to the police for their comparison.

Derek Galpin testified that he sold Chandler his boat. When he sold the boat to Chandler he told him that the English translation for the German name on the back of the boat meant GYPSY. The steering wheel was in pretty bad shape and had a black, very tacky sort of covering. Galpin also sold the residence to Chandler. There were six, seven, or eight rough gray concrete blocks with two square holes in them on the side of the house. Robert Carlton bought the blue and white boat from Chandler in July/August, 1989. The boat trailer was parked on the side of Chandler's house and was sold with the boat. The boat had a V-6 engine in it and a VHF radio in it. When Carlton got the boat from Chandler the interior was real clean. "It was spotless". Carlton recalled seeing concrete blocks at the Chandler house and that some of the concrete blocks had three holes and some had two.

Oba Chandler's daughter, Kristal Mays testified that she lived in Ohio. Chandler left when she was 7 and she did not see him again until the mid-eighties when she hired a detective to find her him. When the detective found Chandler he was incarcerated in Florida. Kristal and her sister, Valerie Lynn Troxell, visited him in the Spring of 1986. Lynn was also Chandler's daughter. Kristal was closer to Chandler than her sister. After Chandler was released from prison, Kristal and her family visited with the Chandler's in Florida. In November of 1989 Chandler called her in Cincinnati and left a number at a Cincinnati motel where he could be reached. Kristal did not know he was coming to visit. Chandler told her that he wanted her and her husband to come to the motel; it was very important. Chandler's Jeep was backed in front of another building, not the building he was staying in. The license plate was up against the building. Kristal remembered that Chandler had a dark colored Jeep vehicle in 1989. Upon entering the motel room, she observed numerous coffee cups, the ashtrays were overflowing with cigarette butts and her father was very anxious and nervous. She had not seen him act like that in the past.

Chandler told them he couldn't go back to Florida because they were looking for him for a rape of a woman. Kristal remembered that Chandler's words were "I can't go back to Florida because the police are looking for me for the rape of a woman." Chandler later called and apologized for the way he had been acting. Chandler did not have luggage or appropriate clothing for that time of year. They had to buy him some clothes. He later told Kristal, she couldn't remember whether he said "dock or pier, but he said that he picked a woman up, and she got away." Chandler did not give Kristal any further explanation of that statement. He told Kristal, "I can't go back to Florida because the police are looking for me because I killed some women." During none of these conversations did Chandler indicate that he was innocent of the things he was talking about. He never once indicated that the police had the wrong man. Chandler never said, "I am innocent of the crime and never said I am the one who murdered the women." Kristal said that Chandler "did not directly to me say, I murdered the women. He did not say that directly to me." After that night, Kristal did not talk about this any more with her father. Chandler directed Kristal not to tell anyone where he was, including his wife, Debbie. Chandler wanted to trade the Jeep he had for the car Kristal had. Chandler did not indicate why he wanted to get rid of his vehicle. While he was there, Chandler sold Kristal some jewelry. At a later point in time, Chandler contacted Kristal and asked her to set up a phone call between he and his wife Debbie. According to the telephone tolls for Kristal's number in 1989, there were a series of phone tolls to Tampa on November 10. Oba had called Kristal and wanted her to call Debbie and tell her to go to a phone booth. He said he couldn't call her at home; he was afraid his lines were tapped.

After Kristal called her, Debbie went to the phone booth, called Kristal and told her she was at the phone booth. Chandler called Kristal back, told her to tell Debbie to go to another phone booth because he thought someone might be following her. Kristal saw Chandler again in October, 1990. Chandler had Kristal's husband set up a drug deal. Chandler wound up taking some money from the drug dealers and leaving her husband literally holding the bag. Kristal's husband was badly beaten up and almost killed. Their house was attacked by the drug dealers at some point. She was in nursing school at the time and she had to drop out and move her family out of the house. Prior to Chandler's going back up to Cincinnati in 1990 and the incident with her husband, Kristal talked with Debra Chandler and Lula Harris about what her father had told her. Kristal asked them if there was any such crime in the state of Florida. They said there was nothing like that going on. Debbie thought he was having a nervous breakdown and told Kristal to tell him to go home. As a result of what they told her, Kristal told her sister Valerie Troxell, but did not call the police. Kristal said that she was upset with her father for what he had done but that she did not hate her father. Kristal wanted Rick to call the police on Chandler; to report to the police that he had put a gun on him. She said that she still did not understand why he did it, but that she was not angry with him anymore.

Chandler was arrested on September 24, 1992 and this incident occurred in October, 1990. After Chandler was arrested Kristal cooperated with law enforcement to try to tape conversations that she had with him. Kristal admitted lying to her father by denying to him that she had cooperated with law enforcement. The purpose of taping the conversations was to try to get some sort of an admission out of Chandler that he had done "this". Kristal had previously been convicted of a crime involving dishonesty. She went on national television, Hard Copy, on January 26, 1994. They paid her $1,000 for her story. Kristal declined an offer to appear on the Maury Povich show. She was aware there was a $25,000 reward for Chandler's conviction but she did not consider herself "in the running for that". Two years before, on October 6, 1992, she gave a sworn statement to the State Attorney's Office concerning the case.

Valerie Lynn Troxell was Kristal Mays' sister and lived in Ohio. She was also Oba Chandler's daughter. Valerie recalled a time in the fall of 1989 when Chandler appeared unexpectedly in Ohio. She remembered him being very anxious. He was extremely upset. He was chain-smoking cigarettes and was different than he was on other occasions when she contacted him. Valerie asked him several times why he was acting that way and Chandler avoided the conversation. Then, he finally said that he had to get rid of a woman in Florida. That she was trying to say that he raped her. He never gave her any more details and he did not indicate that he was innocent or that he hadn't done it. Chandler had not brought any luggage or clothing with him to Ohio that was appropriate for that time of year. He was trying to trade or sell his vehicle. Valerie recalled that it was one of the all-terrain, Jeep-type vehicles. He gave instructions for them to say that they had not seen him if anyone was trying to find him or look for him. Valerie said that Kristal related to her what her father had said to her during his visit to Ohio in 1989. Valerie went on national television, Hard Copy, and received $1,000. She went on the show for the money. The only reason Valerie was upset with Chandler at the time of the trial was because he wrote a letter to her employer telling her the things she had disclosed to the FBI and put Kristal's job in jeopardy.

James Rick Mays lived in Cincinnati and was Kristal Mays's husband. He vacationed at Chandler's house in late July and early August, 1989. While Rick was visiting, Chandler took him on a couple of aluminum jobs during the day. Chandler took Rick to John's Pass on Madeira Beach. During their travels, Chandler at some point began to talk about sex. As they were crossing the bridge, Chandler pointed off to the right, which was John's Pass and said that he picked up a lot of women at that point. He said that he had forcible sex with a lady that he had picked up from that area. Chandler told Rick that he raped somebody and one of them got away. Rick recalled a time in the fall of 1989, approximately November 7 or 9th, when Chandler showed up unexpected in Cincinnati, Ohio. Over the next day or two Rick had contact with Chandler. They rode together on an errand to Dayton. Kristal was not in the car. On the way to Dayton, Rick remembered Chandler saying that he told him they were looking for him for the murder of three women in Florida. The way Chandler talked, Rick thought that he actually did it. In none of the conversations did Chandler indicate to Rick that he was innocent or that the police were looking for the wrong man. Another time during this period Chandler came to their house one evening and Kristal was there. Chandler said he could not go home because of the murders of the women in Florida. When they got back to the house, Chandler was talking a little bit about either the rape or murders although Rick did not recall exactly what he said at that time. Chandler told them to tell anyone who called looking for him that they hadn't seen him. Rick was aware that his wife arranged a phone call between Mr. Chandler and his wife.

Subsequently, in 1990, Chandler went back to the Ohio area. He showed up at the door and said he ripped off the Coast Guard for some marijuana and that he had it tucked away and he wanted to know if Rick knew anybody that he could sell it to. Chandler said he'd pay Rick $6,000 to help him. Rick put Chandler in touch with a guy and they worked out a deal. Rick's role in the transaction was to pick up the money ($29,000) and bring it back to his house. When Rick arrived with the money, Chandler was sitting in the front yard in his pickup and he had his gun out. Rick said, "You know, this isn't the way it's supposed to go." The guy walked around the other side and dropped the money into the other side of the truck and Rick was trying to get the keys away from Chandler so he couldn't start the truck and take off. Chandler brought the gun up to Rick's forehead and said, "Family don't mean shit to me." Chandler hit Rick with the gun and he had to let go. Chandler got the truck started and left with the money. The guys took Rick back to their place. They thought Rick and Chandler were partners. They put a shotgun in Rick's mouth and threatened him. During this time, Chandler called and said, "Guess you know by now, you have been ripped off" and again, "Family don't mean shit to me." Chandler wanted to trade the money back for cocaine. The guys who were the purchasers let Rick go.

When Chandler visited Mays in November, 1989, Rick said that Chandler may have said "accused" or "looking" for the raping of three women, Mr. Kebel testified as to the phone bill of March 31, 1989 for the telephone number 813-854-2823. There was a collect call from Gypsy One in Clearwater billing area on May 15, 1989. The call was placed by the marine operator. There were four calls made on November 10, 1989 from Kristal Mays to the 813-854- 2823 number subscribed to Debra Chandler. Ms. White discussed a toll ticket dated July 5, 1989. A marine call was placed from the boat Cigeuner to 813-854-2823 in Tampa, Florida. The ticket was filled out by the operator at the time the vessel was providing the information to make the call. The name given was Obey, O-b-e-y. The call started at 12:38 a.m. and was a two-minute-and-thirty-one second call. Ms. White testified as to a toll ticket for May 15, 1989 showing a toll call of two minutes eight seconds. This particular call connected at 5:49 p.m. Ms. White testified as to a toll ticket for June 2, 1989 showing a toll call made at 1:12 a.m. Ms. White testified as to a toll ticket for June 2, 1989 showing a connect time of 1:30 a.m. The call was a one-minute call. The length of the call made at one-twelve was five minutes. There was another call made on June 2, 1989 at 8:11 a.m. and the duration was for four minutes. Another call on that same date was made at 9:52 a.m. That call was for one minute. According to the phone bill for 813-854-2823, subscriber Debra Chandler, several marine calls were indicated. The first one was for May 15, 1989. There were others for March 17, 1989 and five calls on June 2, 1989. There was one marine call on July 5, 1989. MS White actually went through and found the toll tickets on the microfiche in 1994. Soraya Butler was a marine operator for GTE in 1989. Ms. Butler received a call on May 15, 1989 at about 5:49 p.m. The caller identified himself as Oba and his boat at Gypsy One. She placed a call for him to Tampa.

Elizabeth Beiro was a marine operator for GTE for 31 years. Ms. Beiro received a call on June 2, 1989 at about 1:12 a.m. The caller identified himself as being boat Gypsy One. The caller did not give a first name. The call was placed to 854- 2823. Toll ticket for 1:30 a.m. on June 2, 1989 was placed by Gypsy One. The caller did not identify himself with a personal name. The collect call was sent to the same number as before. The boat that placed the call on July 5, 1989 at 12:38 a.m was the Zigeuner. The caller gave a personal name of Obey. The call went to 854-2823. Carol Voeller was a marine operator for GTE in 1989. She testified as to toll ticket dated June 2, 1989 at 8:11 a.m. The name of the boat calling was the Gypsy and the person calling did not give a personal name. The collect call was to Tampa number 854-2823. Frances Watkins was a marine operator for GTE in 1989. She testified that a collect call was made on June 2, 1989 at 9:52 a.m. from the boat Gypsy One. The caller identified himself as Obie.

In September, 1992 Detective Halliday interviewed the victim, Judy Blair in the rape case that occurred in Madeira Beach. She described the shirt, shoes and hat that Chandler wore on that occasion. Subsequent to that interview in September, 1992, Detective Hall day participated in a search pursuant to warrant of Chandler's residence in Port Orange. During the search law enforcement located a shirt matching the description given by Judy Blair. Detective Halliday also removed a hat and shoes that matched the general description given by Ms. Blair. The search warrant was issued in the Madeira Beach rape case. It was the next morning that he returned to Mr. Chandler's house and searched. Law enforcement performed a meticulous search of the house. They did not find any ladies' purses, material coming from the purses, or clothing relating to the Rogers' case. The green mesh shirt, hat and shoes were seized in the Madeira Beach case based on Judy Blair's description.