Executed May 29, 2013 06:12 p.m. EST by Lethal Injection in Florida

13th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1333rd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Florida in 2013

76th murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(13) |

|

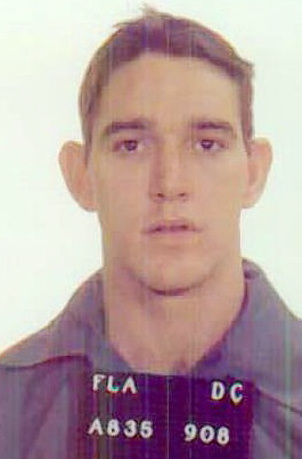

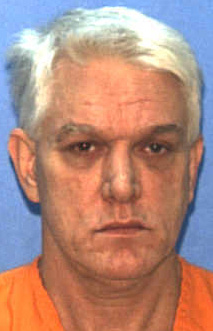

Elmer Leon Caroll W / M / 34 - 56 |

Christine McGowan W / F / 10 |

Citations:

Carroll v. State, 636 So.2d 1316 (Fla. 1994). (Direct Appeal)

Carroll v. State, 815 So.2d 601 (Fla. 2002). (PCR)

Carroll v. Secretary, DOC, 574 F.3d 1354 (11th Cir. 2009). (Habeas)

Final / Special Meal:

Sunny-side-up eggs with bacon and sliced tomatoes, biscuits, avocados, a fruit salad of strawberries, papaya, peaches and pineapple, and canned milk.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

"Florida executes man who raped and killed 10-year-old girl." (Wed May 29, 2013 9:32pm EDT)

MIAMI (Reuters) - A man convicted of raping and strangling a 10-year-old girl who lived next door to the halfway house where he resided more than 20 years ago was executed in Florida on Wednesday, a state prison official said. Elmer Leon Carroll, 56, was pronounced dead at 6:12 p.m. EDT from a lethal injection at the Florida State Prison near Starke, said Ann Howard, a spokesperson for the Florida Department of Corrections.

Carroll was convicted in the 1990 murder of Christine McGowan. Police said Carroll, who lived at a halfway house for ex-convicts and homeless men, broke into the girl's home while her stepfather slept and her mother was at work, and assaulted the fifth-grader in her bed. A Florida jury gave him the death sentence him two years later for murder and sexual battery. The judge in the case called the crime "savage and barbaric."

The execution came as death penalty opponents in Florida plan to present petitions to Governor Rick Scott on Thursday urging him to veto a bill recently passed by the state's legislature that would speed up the death penalty process. The "Timely Justice Act" would set deadlines for condemned killers to file appeals and post-conviction motions in a state that has 404 inmates on death row, more than any other state except California. Supporters of the bill say they want to prevent frivolous appeals that are costly and only end up delaying the executions. Some opponents warn speeding up the process could lead to innocent prisoners being executed.

Before McGowan's killing, Carroll had previously been convicted twice for molesting children. During his trial, a resident at the halfway house said Carroll told him the girl was "cute" and "liked to watch him make boats," according to court documents. Authorities found blood and other evidence at the scene that tied Carroll to the crime.

A last-minute appeal by his lawyers to the U.S. Supreme Court was denied shortly before the execution. Carroll's attorneys argued he was mentally ill when he committed the murder. Carroll was the thirteenth person executed in the United States this year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

"Man executed for rape and murder of girl, 10." (Associated Press Wednesday, May 29, 2013 4:30am)

STARKE — A convicted child molester condemned for the 1990 rape and murder of a 10-year-old Apopka girl was executed Wednesday at the Florida State Prison. Elmer Carroll, 56, was pronounced dead at 6:12 p.m. Wednesday after receiving an injection at the prison in Starke, Gov. Rick Scott's office said.

Carroll was sentenced to die for first-degree murder and sexual battery in the rape and strangling death of Christine McGowan. The girl lived with her family next door to a halfway house for homeless men where Carroll was staying in Apopka.

Five of Christine's family members were among those witnessing the execution. Two of them hugged before walking out, but they did not address the media. When prison officials asked whether he wished to make a final statement, Carroll said, "No sir." A few minutes after the injection procedure began at 6:01 p.m., witnesses could see Carroll's chest rising and falling, and at one point he puffed his cheeks out. He was pronounced dead after a prison physician checked him with a stethoscope.

During Carroll's two decades on death row, his lawyers argued that he was too mentally ill to stand trial or be subjected to the death penalty. The U.S. Supreme Court denied that petition. On Wednesday morning, Carroll ate a last meal of eggs with bacon and biscuits. Carroll had two visitors Wednesday morning — a mitigation specialist and a Catholic priest. No family members visited.

Florida Department of Corrections

DC Number: 835908Incarceration History:

In: 01/10/1980

Out: 05/26/1982

In: 02/02/1983

Out: 04/16/1990

In: 05/29/1992

Out: 05/29/2013

Current Prison Sentence History:

Offense Date-Offense-Sentence Date-County-Case No.-Prison Sentence Length

06/29/1990

AGG BATTERY/W/DEADLY WEAPON

04/16/1992

ORANGE

9011647

15Y 0M 0D

10/28/1990

1ST DEG MUR,COM.OF FELONY

04/16/1992

ORANGE

9012464

DEATH SENTENCE

10/28/1990

SEX BAT BY ADULT/VCTM LT 12

04/16/1992

ORANGE

9012464

SENTENCED TO LIFE

Prior Prison History:

Offense Date-Offense-Sentence Date-County-Case No.-Prison Sentence Length

03/26/1976

L/L, INDEC.ASLT CHILD U/16

01/08/1980

PASCO

6Y 0M 1D

11/14/1982

L/L, INDEC.ASLT CHILD U/16

02/01/1983

PASCO

8202170

15Y 0M 0D

Death Row: Elmer Carroll, 56, was put to death by lethal injection for the rape and murder of Christine McGowan, 10

A convicted child molester condemned for the 1990 rape and murder of a 10-year-old Florida girl was executed Wednesday at the Florida State Prison. Elmer Carroll, 56, was pronounced dead at 6:12 p.m. Wednesday after an injection at the prison in Starke, Florida Gov. Rick Scott's office said. Carroll was sentenced to die for first-degree murder and sexual battery in the rape and strangling death of Christine McGowan. The girl lived with her family next door to a halfway house for homeless men where Carroll was staying in Apopka.

Five of Christine's family members were among those witnessing the execution. Two of them hugged before walking out, and the family issued a statement read to the media by Corrections Department spokeswoman Ann Howard. "Thank you to all that have worked so hard, and justice for all, namely, Christine McGowan. Rest in peace," said the statement from family member Julie McGowan.

Carroll said "no sir" when prison officials asked if he wished to make a final statement. A few minutes after the injection procedure began at 6:01 p.m., witnesses could see Carroll's chest rising and falling, and at one point he puffed his cheeks out. He was pronounced dead after a prison physician checked him with a stethoscope.

During Carroll's two decades on death row, his lawyers argued he was too mentally ill to stand trial or be subjected to the death penalty. The U.S. Supreme Court denied that petition. Carroll, who had been imprisoned twice for indecent assault on a child, had told one of his housemates that the Christine was "cute, sweet and liked to watch him make boats," according to witness testimony at his trial.

Christine's stepfather found the girl dead in her bedroom and noticed that his truck was missing. The truck was found a short time later and an officer came upon Carroll — who had blood on his sweatshirt and genitals, while traces of his semen, saliva and pubic hair were found on Christine, according to court records. Carroll's lawyers employed the insanity defense at his trial, during which they and prosecutors presented conflicting testimony from psychiatrists about Carroll's mental competency.

Carroll had two visitors Wednesday morning, a mitigation specialist and a Catholic priest. No family visited. He also ate a last meal that included eggs, bacon, biscuits, fruit salad and a whole sliced tomato.

His last appeal rejected by the Florida Supreme Court, Elmer Carroll died by lethal injection Wednesday for the 1990 murder of Christine McGowen, a 10-year-old girl from northwest Orange County.

Carroll, 56, died at 6:12 p.m. at Florida State Prison in Starke, the Florida Department of Corrections said. Carroll declined to make a final statement, but Christine's mother, Julie McGowen, issued one: "Thank you to all that have worked so hard, and justice for all, namely, Christine McGowen. Rest in peace."

Carroll raped and strangled Christine in her bed Oct. 30, 1990 while her stepfather slept in another room and her mother was at work. The family lived next door to the halfway house where Carroll was staying after his release from prison. He was convicted of lewd conduct with two other children before he met Christine.

At 10 a.m. Wednesday, Carroll ate a last meal of sunny-side-up eggs with bacon and sliced tomatoes, biscuits, avocados, a fruit salad of strawberries, papaya, peaches and pineapple and canned milk. He had two visitors — death-penalty opponents Susan Cary, a lawyer, and Dale Recinella, a Catholic lay chaplain, author and lawyer.

Orange-Osceola State Attorney Jeff Ashton, who prosecuted the case, attended the execution. "For me, it's completion," Ashton said. At 5 p.m., the Catholic Diocese of Orlando held a service at St. James Cathedral to pray for the death penalty to be abolished. "It's a destructive tool rather than a preventive tool," Bishop John Noonan told about 30 people assembled for the service.

Carroll was written up 20 times in more than 20 years on death row for prison infractions including attempted arson, possession of contraband and, in December, for making threats

On October 30, 1990, at about 6 a.m., Robert Rank went to awaken his ten-year-old stepdaughter, Christine McGowan, at their home in Apopka. When she did not respond to his calls, Robert went to her bedroom and found the door closed when it had been open the night before. She was face-down, under the covers. After shaking the bed, Robert removed the blankets and turned Christine over, then realized she wasn't breathing and was cold to the touch. Shortly thereafter, Robert noticed that his front door was slightly ajar and that his pickup truck he had parked in the yard with the keys in it the night before was missing. When the police arrived, they determined that Christine had been raped and strangled.

Robert Rank said he had locked the door after Christine's mother Julie had left for work around 9:00 pm. He went to bed around 11:00 pm. A BOLO was issued for the missing truck, which was a white construction truck bearing the logo ATC on the side. Shortly thereafter, the truck was seen parked on the side of a highway and 34-year-old Elmer Carroll was observed walking about one mile down the road from the truck. Carroll, who had been released from prison just a few months earlier, was subsequently stopped and searched, and the keys to the truck were found on Carroll.

Two witnesses had also observed Carroll driving the truck earlier that morning. Blood was found on Carroll's sweatshirt and genitalia, and semen, saliva, and pubic hair recovered from the victim were consistent with that of Carroll. The keys to Robert's truck were found in Carroll's possession. Carroll had been living in a travel trailer at the Lighthouse Mission since his release from prison. Christine's house was adjacent to the mission. Carroll had remarked to other residents of the mission about the "cute" girl next door.

The jury convicted Carroll of both charges and recommended death for the first-degree murder conviction by a vote of twelve to zero. The trial court followed the jury's recommendation and sentenced Carroll to death. In so doing, the trial court found the following three aggravating factors: (1) Carroll was previously convicted of two felonies involving the use or threat of violence to the person; (2) the capital felony was committed while Carroll was engaged in the commission of a sexual battery; and (3) the capital felony was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. The trial court found no statutory mitigating circumstances, but found as a non-statutory mitigating circumstance that Carroll suffered from "some possible mental abnormalities and has an antisocial personality."

Following is a list of inmates executed since Florida resumed executions in 1979:

1. John Spenkelink, 30, executed May 25, 1979, for the murder of traveling companion Joe Szymankiewicz in a Tallahassee hotel room.

2. Robert Sullivan, 36, died in the electric chair Nov. 30, 1983, for the April 9, 1973, shotgun slaying of Homestead hotel-restaurant assistant manager Donald Schmidt.

3. Anthony Antone, 66, executed Jan. 26, 1984, for masterminding the Oct. 23, 1975, contract killing of Tampa private detective Richard Cloud.

4. Arthur F. Goode III, 30, executed April 5, 1984, for killing 9-year-old Jason Verdow of Cape Coral March 5, 1976.

5. James Adams, 47, died in the electric chair on May 10, 1984, for beating Fort Pierce millionaire rancher Edgar Brown to death with a fire poker during a 1973 robbery attempt.

6. Carl Shriner, 30, executed June 20, 1984, for killing 32-year-old Gainesville convenience-store clerk Judith Ann Carter, who was shot five times.

7. David L. Washington, 34, executed July 13, 1984, for the murders of three Dade County residents _ Daniel Pridgen, Katrina Birk and University of Miami student Frank Meli _ during a 10-day span in 1976.

8. Ernest John Dobbert Jr., 46, executed Sept. 7, 1984, for the 1971 killing of his 9-year-old daughter Kelly Ann in Jacksonville..

9. James Dupree Henry, 34, executed Sept. 20, 1984, for the March 23, 1974, murder of 81-year-old Orlando civil rights leader Zellie L. Riley.

10. Timothy Palmes, 37, executed in November 1984 for the Oct. 19, 1976, stabbing death of Jacksonville furniture store owner James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Ronald John Michael Straight, executed May 20, 1986.

11. James David Raulerson, 33, executed Jan. 30, 1985, for gunning down Jacksonville police Officer Michael Stewart on April 27, 1975.

12. Johnny Paul Witt, 42, executed March 6, 1985, for killing, sexually abusing and mutilating Jonathan Mark Kushner, the 11-year-old son of a University of South Florida professor, Oct. 28, 1973.

13. Marvin Francois, 39, executed May 29, 1985, for shooting six people July 27, 1977, in the robbery of a ``drug house'' in the Miami suburb of Carol City. He was a co-defendant with Beauford White, executed Aug. 28, 1987.

14. Daniel Morris Thomas, 37, executed April 15, 1986, for shooting University of Florida associate professor Charles Anderson, raping the man's wife as he lay dying, then shooting the family dog on New Year's Day 1976.

15. David Livingston Funchess, 39, executed April 22, 1986, for the Dec. 16, 1974, stabbing deaths of 53-year-old Anna Waldrop and 56-year-old Clayton Ragan during a holdup in a Jacksonville lounge.

16. Ronald John Michael Straight, 42, executed May 20, 1986, for the Oct. 4, 1976, murder of Jacksonville businessman James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Timothy Palmes, executed Jan. 30, 1985.

17. Beauford White, 41, executed Aug. 28, 1987, for his role in the July 27, 1977, shooting of eight people, six fatally, during the robbery of a small-time drug dealer's home in Carol City, a Miami suburb. He was a co-defendant with Marvin Francois, executed May 29, 1985.

18. Willie Jasper Darden, 54, executed March 15, 1988, for the September 1973 shooting of James C. Turman in Lakeland.

19. Jeffrey Joseph Daugherty, 33, executed March 15, 1988, for the March 1976 murder of hitchhiker Lavonne Patricia Sailer in Brevard County.

20. Theodore Robert Bundy, 42, executed Jan. 24, 1989, for the rape and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach of Lake City at the end of a cross-country killing spree. Leach was kidnapped Feb. 9, 1978, and her body was found three months later some 32 miles west of Lake City.

21. Aubry Dennis Adams Jr., 31, executed May 4, 1989, for strangling 8-year-old Trisa Gail Thornley on Jan. 23, 1978, in Ocala.

22. Jessie Joseph Tafero, 43, executed May 4, 1990, for the February 1976 shooting deaths of Florida Highway Patrolman Phillip Black and his friend Donald Irwin, a Canadian constable from Kitchener, Ontario. Flames shot from Tafero's head during the execution.

23. Anthony Bertolotti, 38, executed July 27, 1990, for the Sept. 27, 1983, stabbing death and rape of Carol Ward in Orange County.

24. James William Hamblen, 61, executed Sept. 21, 1990, for the April 24, 1984, shooting death of Laureen Jean Edwards during a robbery at the victim's Jacksonville lingerie shop.

25. Raymond Robert Clark, 49, executed Nov. 19, 1990, for the April 27, 1977, shooting murder of scrap metal dealer David Drake in Pinellas County.

26. Roy Allen Harich, 32, executed April 24, 1991, for the June 27, 1981, sexual assault, shooting and slashing death of Carlene Kelly near Daytona Beach.

27. Bobby Marion Francis, 46, executed June 25, 1991, for the June 17, 1975, murder of drug informant Titus R. Walters in Key West.

28. Nollie Lee Martin, 43, executed May 12, 1992, for the 1977 murder of a 19-year-old George Washington University student, who was working at a Delray Beach convenience store.

29. Edward Dean Kennedy, 47, executed July 21, 1992, for the April 11, 1981, slayings of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Howard McDermon and Floyd Cone after escaping from Union Correctional Institution.

30. Robert Dale Henderson, 48, executed April 21, 1993, for the 1982 shootings of three hitchhikers in Hernando County. He confessed to 12 murders in five states.

31. Larry Joe Johnson, 49, executed May 8, 1993, for the 1979 slaying of James Hadden, a service station attendant in small north Florida town of Lee in Madison County. Veterans groups claimed Johnson suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

32. Michael Alan Durocher, 33, executed Aug. 25, 1993, for the 1983 murders of his girlfriend, Grace Reed, her daughter, Candice, and his 6-month-old son Joshua in Clay County. Durocher also convicted in two other killings.

33. Roy Allen Stewart, 38, executed April 22, 1994, for beating, raping and strangling of 77-year-old Margaret Haizlip of Perrine in Dade County on Feb. 22, 1978.

34. Bernard Bolander, 42, executed July 18, 1995, for the Dade County murders of four men, whose bodies were set afire in car trunk on Jan. 8, 1980.

35. Jerry White, 47, executed Dec. 4, 1995, for the slaying of a customer in an Orange County grocery store robbery in 1981.

36. Phillip A. Atkins, 40, executed Dec. 5, 1995, for the molestation and rape of a 6-year-old Lakeland boy in 1981.

37. John Earl Bush, 38, executed Oct. 21, 1996, for the 1982 slaying of Francis Slater, an heir to the Envinrude outboard motor fortune. Slater was working in a Stuart convenience store when she was kidnapped and murdered.

38. John Mills Jr., 41, executed Dec. 6, 1996, for the fatal shooting of Les Lawhon in Wakulla and burglarizing Lawhon's home.

39. Pedro Medina, 39, executed March 25, 1997, for the 1982 slaying of his neighbor Dorothy James, 52, in Orlando. Medina was the first Cuban who came to Florida in the Mariel boat lift to be executed in Florida. During his execution, flames burst from behind the mask over his face, delaying Florida executions for almost a year.

40. Gerald Eugene Stano, 46, executed March 23, 1998, for the slaying of Cathy Scharf, 17, of Port Orange, who disappeared Nov. 14, 1973. Stano confessed to killing 41 women.

41. Leo Alexander Jones, 47, executed March 24, 1998, for the May 23, 1981, slaying of Jacksonville police Officer Thomas Szafranski.

42. Judy Buenoano, 54, executed March 30, 1998, for the poisoning death of her husband, Air Force Sgt. James Goodyear, Sept. 16, 1971.

43. Daniel Remeta, 40, executed March 31, 1998, for the murder of Ocala convenience store clerk Mehrle Reeder in February 1985, the first of five killings in three states laid to Remeta.

44. Allen Lee ``Tiny'' Davis, 54, executed in a new electric chair on July 8, 1999, for the May 11, 1982, slayings of Jacksonville resident Nancy Weiler and her daughters, Kristina and Katherine. Bleeding from Davis' nose prompted continued examination of effectiveness of electrocution and the switch to lethal injection.

45. Terry M. Sims, 58, became the first Florida inmate to be executed by injection on Feb. 23, 2000. Sims died for the 1977 slaying of a volunteer deputy sheriff in a central Florida robbery.

46. Anthony Bryan, 40, died from lethal injection Feb. 24, 2000, for the 1983 slaying of George Wilson, 60, a night watchman abducted from his job at a seafood wholesaler in Pascagoula, Miss., and killed in Florida.

47. Bennie Demps, 49, died from lethal injection June 7, 2000, for the 1976 murder of another prison inmate, Alfred Sturgis. Demps spent 29 years on death row before he was executed.

48. Thomas Provenzano, 51, died from lethal injection on June 21, 2000, for a 1984 shooting at the Orange County courthouse in Orlando. Provenzano was sentenced to death for the murder of William ``Arnie'' Wilkerson, 60.

49. Dan Patrick Hauser, 30, died from lethal injection on Aug. 25, 2000, for the 1995 murder of Melanie Rodrigues, a waitress and dancer in Destin. Hauser dropped all his legal appeals.

50. Edward Castro, died from lethal injection on Dec. 7, 2000, for the 1987 choking and stabbing death of 56-year-old Austin Carter Scott, who was lured to Castro's efficiency apartment in Ocala by the promise of Old Milwaukee beer. Castro dropped all his appeals.

51. Robert Glock, 39 died from lethal injection on Jan. 11, 2001, for the kidnapping murder of a Sharilyn Ritchie, a teacher in Manatee County. She was kidnapped outside a Bradenton shopping mall and taken to an orange grove in Pasco County, where she was robbed and killed. Glock's co-defendant Robert Puiatti remains on death row.

52. Rigoberto Sanchez-Velasco, 43, died of lethal injection on Oct. 2, 2002, after dropping appeals from his conviction in the December 1986 rape-slaying of 11-year-old Katixa ``Kathy'' Ecenarro in Hialeah. Sanchez-Velasco also killed two fellow inmates while on death row.

53. Aileen Wuornos, 46, died from lethal injection on Oct. 9, 2002, after dropping appeals for deaths of six men along central Florida highways.

54. Linroy Bottoson, 63, died of lethal injection on Dec. 9, 2002, for the 1979 murder of Catherine Alexander, who was robbed, held captive for 83 hours, stabbed 16 times and then fatally crushed by a car.

55. Amos King, 48, executed by lethal inection for the March 18, 1977 slaying of 68-year-old Natalie Brady in her Tarpon Spring home. King was a work-release inmate in a nearby prison.

56. Newton Slawson, 48, executed by lethal injection for the April 11, 1989 slaying of four members of a Tampa family. Slawson was convicted in the shooting deaths of Gerald and Peggy Wood, who was 8 1/2 months pregnant, and their two young children, Glendon, 3, and Jennifer, 4. Slawson sliced Peggy Wood's body with a knife and pulled out her fetus, which had two gunshot wounds and multiple cuts.

57. Paul Hill, 49, executed for the July 29, 1994, shooting deaths of Dr. John Bayard Britton and his bodyguard, retired Air Force Lt. Col. James Herman Barrett, and the wounding of Barrett's wife outside the Ladies Center in Pensacola.

58. Johnny Robinson, died by lethal injection on Feb. 4, 2004, for the Aug. 12, 1985 slaying of Beverly St. George was traveling from Plant City to Virginia in August 1985 when her car broke down on Interstate 95, south of St. Augustine. He abducted her at gunpoint, took her to a cemetery, raped her and killed her.

59. John Blackwelder, 49, was executed by injection on May 26, 2004, for the calculated slaying in May 2000 of Raymond Wigley, who was serving a life term for murder. Blackwelder, who was serving a life sentence for a series of sex convictions, pleaded guilty to the slaying so he would receive the death penalty.

60. Glen Ocha, 47, was executed by injection April 5, 2005, for the October, 1999, strangulation of 28-year-old convenience store employee Carol Skjerva, who had driven him to his Osceola County home and had sex with him. He had dropped all appeals.

61. Clarence Hill 20 September 2006 lethal injection Stephen Taylor Jeb Bush

62. Arthur Dennis Rutherford 19 October 2006 lethal injection Stella Salamon Jeb Bush

63. Danny Rolling 25 October 2006 lethal injection Sonja Larson, Christina Powell, Christa Hoyt, Manuel R. Taboada, and Tracy Inez Paules

64. Ángel Nieves Díaz 13 December 2006 lethal injection Joseph Nagy

65. Mark Dean Schwab 1 July 2008 lethal injection Junny Rios-Martinez, Jr.

66. Richard Henyard 23 September 2008 lethal injection Jamilya and Jasmine Lewis

67. Wayne Tompkins 11 February 2009 lethal injection Lisa DeCarr

68. John Richard Marek 19 August 2009 lethal injection Adela Marie Simmons

69. Martin Grossman 16 February 2010 lethal injection Margaret Peggy Park

70. Manuel Valle 28 September 2011 lethal injection Louis Pena

71. Oba Chandler 15 November 2011 lethal injection Joan Rogers, Michelle Rogers and Christe Rogers

72. Robert Waterhouse 15 February 2012 lethal injection Deborah Kammerer

73. David Alan Gore 12 April 2012 lethal injection Lynn Elliott

74. Manuel Pardo 11 December 2012 lethal injection Mario Amador, Roberto Alfonso, Luis Robledo, Ulpiano Ledo, Michael Millot, Fara Quintero, Fara Musa, Ramon Alvero, Daisy Ricard.

75. Larry Eugene Mann 10 April 2013 lethal injection Elisa Nelson

76. Elmer Leon Carroll 29 May 2013 lethal injection Christine McGowan

Florida Commission on Capital Cases

Inmate: Carroll Elmer

Last Action

06/08/05 USDC 05-857 Habeas

Current Attorney: Reiter, Michael P., Venice, FL

Last Updated: 2008-01-09 12:32:11.0

Case Summary:

Ninth Judicial Circuit, Orange County, Case #90-12464

Circumstances of Offense:

Elmer Carroll was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of 10-year-old Christine McGowan on 10/30/90.

Robert Rank attempted to wake his stepdaughter, Christine McGowan, on the morning of 10/30/90 and, when she did not answer his calls, Rank went to McGowan’s room. He noticed her door, which was open the night before, was closed. Upon entering the room, Rank discovered McGowan face down on the bed. She had blood between her legs and her body was cold to the touch. Rank then noticed that the front door was slightly open and his construction truck was missing. Police investigators at the scene determined that McGowan had been raped and strangled to death, and issued a bulletin regarding the stolen construction truck.

Upon hearing a radio bulletin regarding the stolen construction truck, Debbie Hyatt notified police that she remembered seeing the abandoned truck and a man, later identified as Elmer Carroll, walking easterly away from the truck. As a result of Hyatt’s tip, Carroll was arrested. When law enforcement officers searched Carroll for weapons, they found a box cutter and the keys to the stolen construction truck.

Information presented at trial revealed that Carroll was a resident of the halfway house located next door to the victim’s home and that Carroll had remarked to other residents about the “cute” girl next door. DNA evidence recovered from the scene matched Carroll’s saliva, semen and pubic hair, and after his arrest, blood was found on Carroll’s sweatshirt and penis.

Prior Incarceration History in the State of Florida:

Offense Date: 03/26/1976

Offense Date: 11/14/1982

Trial Summary:

10/30/90 Defendant arrested.

11/26/90 Defendant indicted on: Count I: First-Degree Murder, Count II: Sexual Battery Under 12

04/13/92 The jury found the defendant guilty on both counts.

04/13/92 Upon advisory sentencing, the jury, by a 12 to 0 majority, voted for the death penalty.

04/16/92 The defendant was sentenced as follows: Count I: First-Degree Murder – Death; Count II: Sexual Battery W/ Victim Under 12 – Life

Appeal Summary:

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal

05/07/92 Appeal filed.

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

United States District Court, Middle District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit – Habeas Appeal

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Factors Contributing to the Delay in the Imposition of the Sentence:

In December 1994, Carroll was granted a time extension in filing a Motion to Vacate Judgment and Sentence (3.850) until February 1, 1996. Statutorily, a defendant has one year from the rehearing denial date in which to file a 3.850 Motion. With his motion for rehearing denied on 06/09/94, the time lapse between filing was approximately one year and seven months. Other than the filing extension, there have been no unreasonable delays at this time.

Case Information:

Carroll filed a Direct Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court on 05/07/92. In that appeal, Carroll alleged that the keys that linked him to Rank’s construction truck should have been suppressed as evidence because they were found as a result of an illegal arrest. Next, Carroll contended that testimony of one of the deputies unfairly and prejudicially commented on his refusal to testify, and he also argued several improper questions asked of a psychiatrist on cross-examination by the prosecutor. In reference to the penalty phase of the trial, Carroll argued the application of the heinous, atrocious, and cruel (HAC) aggravating factor and that the trial court erred in failing to consider certain statutory mitigating evidence. The Florida Supreme Court affirmed the convictions and sentence of death on 04/14/94.

Subsequently, Carroll filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the United States Supreme Court, which was denied on 10/31/94.

On 02/01/96, Carroll filed a Motion to Vacate Judgment and Sentence (3.850) in the State Circuit Court. That motion was denied on 10/20/98, after which Carroll filed an appeal in the Florida Supreme Court on 12/31/98, which was denied on 03/07/02.

Carroll also filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus in the Florida Supreme Court on 01/10/00, which was denied on 03/07/02.

On 4/22/03, Carroll filed another 3.850 Motion in the State Circuit Court that was denied on 01/12/04. Carroll filed an appeal of that decision in the Florida Supreme Court on 02/09/04. On 05/12/05, the FSC affirmed the denial of the Motion.

Carroll filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the U.S. District Court, Middle District, on 06/08/05 that was denied on 06/20/08.

On 12/04/08, Carroll filed a Habeas Appeal with the United States Court of Appeals. The United States Court of Appeals affirmed the lower courts disposition and denied the Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus.

On 08/24/09, Carroll filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari with the United States Supreme Court that was denied on 11/02/09.

Institutional Adjustment:

DATE DAYS VIOLATION LOCATION

10/14/92 30 POSS OF UNAUTH BEV. FSP

Carroll v. State, 636 So.2d 1316 (Fla. 1994). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in Circuit Court, Orange County, Belvin Perry, J., for first-degree murder and sexual battery on child under 12 years old, was sentenced to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court held that: (1) officer had grounds for investigatory stop of defendant who was walking alone on highway, and keys taken from defendant during search for weapons were not fruit of illegal arrest, and (2) trial court properly found that murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel and that defendant was able to appreciate criminality of his conduct and could have conformed his conduct to requirements of law. Affirmed. Shaw, J., concurred in result only.

PER CURIAM.

Elmer Leon Carroll appeals his convictions for first-degree murder and sexual battery on a child under twelve years old and his resulting sentences, including the sentence of death. We have jurisdiction under article V, section 3(b)(1) of the Florida Constitution, and affirm the convictions and sentences.

On October 30, 1990, at about 6 a.m., Robert Rank went to awaken his ten-year-old stepdaughter, Christine McGowan, at their home in Apopka. When she did not respond to his calls, Rank went into her bedroom and found her dead. Shortly thereafter, Rank noticed that his front door was slightly ajar and that his pickup truck he had parked in the yard with the keys in it the night before was missing. When the police arrived, they determined that Christine had been raped and strangled. A BOLO was issued for the missing truck, which was a white construction truck bearing the logo ATC on the side.

Debbie Hyatt saw a white pickup truck parked near her residence east of Orlando on Highway 50 as she left for work about 6:50 a.m. About a mile down the road, she saw a man whom she later identified as Carroll walking in an easterly direction along the highway away from the truck. She described him as having long scraggly hair and wearing a brown jacket. She did not think too much about it until she later heard over the radio that the police were looking for a white pickup truck bearing the ATC logo. After checking to see that the truck she had seen had the ATC logo described in the radio bulletin, she called the police. When sheriff's deputies arrived, she told them about first seeing the truck and the man walking down the road.

Carl Young, a state wildlife officer, was travelling on State Road 520 in Orange County on the morning of October 30, 1990. At a point near the intersection of Highway 50, Young noticed a man with shoulder length hair wearing a brown jacket walking down the highway. Young thought this was strange because he was not carrying anything. The man looked back over his shoulder at Young as he passed. After turning onto Highway 50 and proceeding west, he saw a deputy sheriff behind a white pickup truck with his revolver drawn. Young went back to the scene to render assistance. By this time, another deputy had arrived, and he heard Debbie Hyatt tell them about the man she had seen walking down the highway away from the truck. Young recalled that her description resembled the person that he had just passed. Young drove back to where Carroll was continuing to walk down the road. Young called to him, but he kept on walking. Young pulled his gun and ordered Carroll to lie down on the ground. Young made a search for weapons and found a box cutter razor blade and some keys. Through radio communication with a deputy who remained at Rank's truck, it was determined that a number on the keys matched a number on the truck. Young and a deputy who had arrived to assist him then placed Carroll under arrest.

At the trial, two other witnesses testified that they had seen the man they identified as Carroll about 6 a.m. at a 7–11 store near Apopka. The witnesses said that Carroll was driving a white truck with the ATC logo. It was also discovered that Carroll was a resident of a halfway house located next door to the Rank home. A resident of the halfway house testified that Carroll had told him that the girl who lived next door was “cute, sweet and liked to watch him make boats.” She was seen talking to a man next door who may have been Carroll the day before the murder. Semen, saliva, and pubic hair recovered from the victim were consistent with that of Carroll. One DNA profile of a specimen obtained from the victim matched Carroll's DNA profile. Blood was found on Carroll's sweatshirt and on his penis.

In addition to contesting guilt, Carroll raised the defense of insanity. The State and the defense presented conflicting psychiatric testimony on the issue of competence. The jury found Carroll guilty of both charges. Following a penalty phase proceeding, the jury returned a recommendation of death by a vote of 12–0. Thereafter, the trial judge sentenced Carroll to death.

GUILT PHASE

Carroll first argues that the court should have suppressed the keys that tied *1318 him to Rank's truck because he had been illegally arrested when the keys were discovered. He insists that he had been arrested without probable cause by the time he was held at gunpoint and made to lie down on the ground. He asserts that the keys and all the evidence seized from his person, including the hair and blood samples, and the DNA test must be suppressed as fruits of the poisonous tree. Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471, 83 S.Ct. 407, 9 L.Ed.2d 441 (1963). The State responds that Carroll was not arrested until after the keys were found and that the trial judge was correct in finding that Carroll had been stopped upon a well-founded or reasonable suspicion. The State says that the keys were properly seized pursuant to Officer Young's search for weapons. We agree.

The fact that Carroll had been seen walking along a deserted highway in the vicinity of and in a direction away from the abandoned truck, together with the other circumstances known to Officer Young, were sufficient for him to temporarily detain Carroll pursuant to the principles of Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 88 S.Ct. 1868, 20 L.Ed.2d 889 (1968). The stop was not necessarily converted into an arrest because the officer drew his gun and directed Carroll to lie on the ground. See State v. Ruiz, 526 So.2d 170 (Fla. 3d DCA) (investigatory stop not converted into arrest even though officers with guns drawn directed defendant to lie prone on the ground), review denied, 534 So.2d 401 (Fla.1988), cert. denied, 488 U.S. 1044, 109 S.Ct. 872, 102 L.Ed.2d 995 (1989); State v. Perera, 412 So.2d 867 (Fla. 2d DCA) (fact that officers had weapons drawn did not convert temporary detention into formal arrest), review denied, 419 So.2d 1199 (Fla.1982).

During the course of an investigatory stop, the police are entitled to take such action as is reasonable under the circumstances. Reynolds v. State, 592 So.2d 1082 (Fla.1992). Because Officer Young was questioning a person who may have recently committed a murder, he was justified in being concerned, and his actions were reasonable. He was entitled to make a search for weapons, and found a razor blade during the search. The officer testified that he then felt an object in Carroll's pocket which was hard to his touch. He said he thought that it might be a weapon. When he removed it, he found that it was a set of keys. There is sufficient evidence in the record to support the trial judge's denial of the motion to suppress. See Doctor v. State, 596 So.2d 442 (Fla.1992) (in the course of legitimate frisk for weapons during temporary stop, police may seize weapons or objects which reasonably could be weapons).

Carroll also complains that in his testimony one of the deputies made two unsolicited remarks which were fairly susceptible of being interpreted by the jury as a comment on Carroll's failure to testify. The trial court denied defendant's motions for mistrial, and in each instance offered to give a curative instruction which was refused. At the outset, we do not believe that the statements at issue were fairly susceptible as being interpreted as comments upon Carroll's failure to testify. In any event, even if they could have been so interpreted, we are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that any error was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt. State v. DiGuilio, 491 So.2d 1129 (Fla.1986). See Brannin v. State, 496 So.2d 124 (Fla.1986) (impermissible comment on right to remain silent held harmless error where actual guilt was largely uncontested and primary theory of defense was based on insanity).

Carroll also complains of certain questions the prosecutor asked Dr. Danziger, a psychiatrist, on cross-examination. Dr. Danziger had studied Carroll's previous medical records in preparation for his testimony that Carroll was insane at the time the crime was committed by reason of an alcoholic blackout. The prosecutor asked him whether he considered among those records the reports of two instances in which Carroll had used the theory of an alcoholic blackout to defend against charges of committing sexual acts with children. After the defense's objection and motion for mistrial were denied, the doctor admitted that the records reflected these facts, but he did not know whether they were so. Contrary to Carroll's argument, the prosecutor was entitled to cross-examine Dr. Danziger as to those portions of the records which he admitted he *1319 considered that were inconsistent with his diagnosis. See Parker v. State, 476 So.2d 134 (Fla.1985).

The prosecutor also asked Dr. Danziger if Carroll had been in State custody for most of the last ten years and if, during that time, he had been subject to frequent observation by mental health professionals. The purpose of the question was to demonstrate that on only one occasion had any mental health professional recorded an act which could be classified as a psychotic symptom such as that testified to by Dr. Danziger. Considering the minimal relevance of the inquiry, we believe that the prosecutor's reference to state custody was erroneous and that defendant's objection should have been sustained. However, the error was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt. Finally, Dr. Danziger was asked whether or not Carroll would still desire to have sex with young children when his schizophrenia was in remission. The judge properly sustained the objection. We find no abuse of discretion in the denial of the defendant's motion for mistrial. See Johnston v. State, 497 So.2d 863 (Fla.1986).

We summarily deny Carroll's contention that the trial judge erred in denying his motions with respect to the propriety of the DNA testing. See Correll v. State, 523 So.2d 562 (Fla.), cert. denied, 488 U.S. 871, 109 S.Ct. 183, 102 L.Ed.2d 152 (1988); Robinson v. State, 610 So.2d 1288 (Fla.1992), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 1170, 114 S.Ct. 1205, 127 L.Ed.2d 553 (1994). Defense counsel was permitted to voir dire and extensively cross-examine the State's expert.

PENALTY PHASE

In his sentencing order, the trial judge found three aggravating circumstances: (1) Carroll was previously convicted of two previous felonies involving the use or threat of violence to the person; (2) the capital felony was committed while Carroll was engaged in the commission of a sexual battery; (3) the capital felony was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. The judge found no statutory mitigating factors but concluded as a statutory mitigating factor that Carroll suffered from “some possible mental abnormalities and has an antisocial personality.”

Carroll first argues that the court improperly found that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. On this point, the trial judge made the following findings:

On the evening of October 29, 1990, Christine McGowan went to bed at approximately 8:00 p.m. She was alone at home with her step-father, Robert Rank. Mr. Rank went to bed around 11:00 p.m. He got up at about 12:00 a.m. to get a drink of tea. Prior to returning to bed he checked on Christine and did not find anything amiss.

Mr. Rank woke up just before 6:00 a.m. and went out to check on the noise being made by a dog. He then went to Christine's room, where he found the door closed. (The door to her room was open at 12:00 a.m.) He opened the door and found Christine face down on the bed. While attempting to wake her, he noticed blood between her legs and that she felt cold. Mr. Rank then summoned help.

Dr. Thomas Hegert testified at the trial and the sentencing hearing to the following:

1. That he performed an autopsy on Christine McGowan on October 30, 1990.

2. That the cause of death in this case was due to asphyxia or lack of oxygen to the brain as a result of mechanical obstruction of the airway, i.e., strangulation.

3. That the victim had injuries to her mouth-upper lip that was consistent with someone holding a hand over the child's mouth and pressing downward.

4. That the victim had a blunt force trauma injury to the left side of her head that was consistent with a blow to the head.

5. That the victim had injuries to her neck that consisted of abrasions and contusions.

6. That the victim's vagina was torn between 4:00 o'clock and 8:00 o'clock and there were contusions around the vagina. That these injuries were consistent with sexual intercourse.

7. That the type of pain that the victim experienced as a result of the tearing or ripping of her vagina was consistent with the pain associated with child birth.

8. That there was a blue contusion about the anal opening of the victim, along with redness and irritation of the rectum of the victim. Dr. Hegert said those injuries were consistent with attempted penetration of the anus by a penis or other object of similar configuration.

9. That the blow to the head of the victim would not have caused her to become unconscious and he was of the opinion that she was conscious during this ordeal.

10. That it would take 3 to 4 minutes to cause death by complete obstruction of the airways.

11. That the victim would be conscious 1 to 2 minutes before losing consciousness.

12. That the victim would be aware of what was going on and would be subject to the fear and apprehension of not being able to breathe.

13. That the victim was alive and conscious when the injuries to her vagina occurred and could feel pain.

The evidence clearly establishes beyond a reasonable doubt that young Christine McGowan did not meet a swift, merciful and relatively painless death. The Defendant on the night in question entered her home without leaving a sign of forced entry. The evidence showed Christine McGowan received a blow to her head, as she was more than likely trying with all the fiber of her being to resist this uncivilized and barbaric attack. The evidence showed that the Defendant with his penis literally ripped her vagina apart while he raped her. The evidence also showed he attempted to have anal intercourse with her.

The agony, the pain, the horror that this child must have suffered prior to her death is evident. The pain that she endured as a result of this savage and barbaric act coupled with the knowledge that she was not able to breathe is beyond comprehension. Death by strangulation is not instantaneous. Dr. Hegert testified she would be conscious for one to two minutes prior to becoming unconscious. During this time, this child of tender years would experience fear, anxiety, emotional strain and perhaps the foreknowledge of impending doom.

If any crime meets the definition of heinous, atrocious or cruel, it is this case. The Court finds this aggravating factor present.

This finding was supported by the evidence.

Carroll also argues that the court erroneously rejected the statutory mitigating circumstances (1) that the murder was committed while Carroll was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance and (2) that his capacity to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was substantially impaired. Referring to the first of these mitigating circumstances in the sentencing order, the judge extensively reviewed the testimony of several mental health experts as well as other witnesses and concluded with the following statement:

Based upon all the testimony there are two conclusions one could arrive at after reviewing the testimony. One, the Defendant at the time of the murder was under the influence of an extreme mental or emotional disturbance. Or that the Defendant was not under the influence of an extreme mental or emotional disturbance at the time of the murder and that his actions prior to the murder were typical of a person with an antisocial personality.

In determining whether a mitigating circumstance is applicable in a given case, the trial court may accept or reject the testimony of an expert witness just as the court may accept or reject the testimony of any other witness. Bates v. State, 506 So.2d 1033 (Fla.1987).

The Court after carefully evaluating and analyzing the testimony of Doctors McMann, Danziger, and Benson finds that their testimony is not sufficient to establish this mitigating factor to the standard required by law. This Court is not reasonably convinced that this crime was committed while the Defendant was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance. There is no testimony from *1321 any witness that the Defendant was exhibiting any bizarre behavioral characteristics at the time of the murder or sexual battery. On the contrary, the evidence showed that these were the acts of a cold-blooded; heartless; child molester-killer who stealthily entered the victim's home; raped and murdered her; took her step-father's vehicle and later had a cup of coffee at the 7–11.

The judge also found that while Carroll may have been emotionally disturbed to some degree, the evidence established that he was able to appreciate the criminality of his conduct and that he could have conformed his conduct to the requirements of the law. The testimony concerning Carroll's mental condition was in sharp conflict, and the judge was entitled to make this finding. We reject Carroll's contention that the mitigating factors outweighed the appropriate aggravating factors.

Accordingly, we affirm both of Carroll's convictions and sentences, including the sentence of death. It is so ordered.

BARKETT, C.J., and OVERTON, McDONALD, GRIMES, KOGAN and HARDING, JJ., concur. SHAW, J., concurs in result only.

Carroll v. State, 815 So.2d 601 (Fla. 2002). (PCR)

Defendant, who was convicted of first-degree murder and sexual battery on child under 12 years old and sentenced to death, filed motion for postconviction relief. The Circuit Court, Orange County, Belvin Perry, J., denied motion. Defendant appealed and filed petition for writ of habeas corpus. The Supreme Court held that: (1) defendant was not deprived of right to effective assistance of trial, or of appellate, counsel; (2) State did not improperly withhold Brady material; and (3) prosecutor's comments did not rise to level of fundamental error. Affirmed, and petition denied. Wells, C.J., concurred in the result.

PER CURIAM.

Elmer Leon Carroll, a prisoner under sentence of death, appeals the trial court's denial of his motion for postconviction relief pursuant to Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.850, and he petitions this Court for a writ of habeas corpus. We have jurisdiction. See art. V, § 3(b)(1), (9), Fla. Const. For the reasons set forth below, we affirm the trial court's order denying Carroll postconviction relief. We also deny Carroll's petition for writ of habeas corpus.

BACKGROUND

Carroll was convicted for first-degree murder and sexual battery on a child under twelve years of age. The facts in this case are set forth in greater detail in Carroll v. State, 636 So.2d 1316 (Fla.1994). The relevant facts are as follows:

On October 30, 1990, at about 6 a.m., Robert Rank went to awaken his ten-year-old stepdaughter, Christine McGowan, at their home in Apopka. When she did not respond to his calls, Rank went into her bedroom and found her dead. Shortly thereafter, Rank noticed that his front door was slightly ajar and that his pickup truck he had parked in the yard with the keys in it the night before was missing. When the police arrived, they determined that Christine had been raped and strangled. A BOLO was issued for the missing truck, which was a white construction truck bearing the logo ATC on the side.

Id. at 1317. Shortly thereafter, the truck was seen parked on the side of a highway and Carroll was observed walking about one mile down the road from the truck. Carroll was subsequently stopped and searched, and the keys to the truck were found on Carroll. Two witnesses had also observed Carroll driving the truck earlier that morning. Blood was found on Carroll's sweatshirt and genitalia, and semen, saliva, and pubic hair recovered from the victim were consistent with that of Carroll.

The jury convicted Carroll of both charges and recommended death for the first-degree murder conviction by a vote of twelve to zero. See id. at 1317. The trial court followed the jury's recommendation and sentenced Carroll to death.FN1 We affirmed Carroll's conviction and sentence on *608 direct appeal. See id. at 1321. The United States Supreme Court denied Carroll's petition for writ of certiorari on October 31, 1994. See Carroll v. Florida, 513 U.S. 973, 115 S.Ct. 447, 130 L.Ed.2d 357 (1994).

FN1. In so doing, the trial court found the following three aggravating factors: (1) Carroll was previously convicted of two felonies involving the use or threat of violence to the person; (2) the capital felony was committed while Carroll was engaged in the commission of a sexual battery; and (3) the capital felony was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. See id. at 1319. The trial court found no statutory mitigating circumstances, but found as a nonstatutory mitigating circumstance that Carroll suffered from “some possible mental abnormalities and has an antisocial personality.” Id.

Carroll timely filed his initial 3.850 motion on February 1, 1996. Thereafter, Carroll filed an amended 3.850 motion raising twenty-four claims. FN2 Following a HuffFN3 hearing, the trial court ordered that an evidentiary hearing be held as to five of the twenty-four claims raised in Carroll's amended motion.FN4 The trial court held an evidentiary hearing on August 4–5, 1997. Subsequent to this hearing, the trial court entered an order denying relief on all of Carroll's claims. This appeal follows.

FN2. These claims included: (1) Carroll is being denied his right to effective representation because CCRC lacks sufficient funds; (2) public records are being withheld; (3) ineffective assistance of counsel during the penalty phase; (4) the Florida Bar rules' prohibition against interviewing jurors is unconstitutional; (5) jury instructions on prior conviction of a violent felony aggravator, engaged in the commission of a sexual battery aggravator, avoiding lawful arrest aggravator, and heinous, atrocious, or cruel aggravator were improper; (6) ineffective assistance of counsel during the guilt phase; (7) State withheld evidence in violation of Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 83 S.Ct. 1194, 10 L.Ed.2d 215 (1963); (8) Florida's statute setting forth the aggravating circumstances to be considered in a capital case is facially vague and overbroad; (9) ineffectiveness of counsel denied Carroll his rights to adequate mental health assistance pursuant to Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985); (10) ineffective assistance of counsel to the extent counsel conceded admissibility by failing to object to the introduction of certain photographs into evidence; (11) Carroll was denied constitutional rights when the judge and prosecutor impermissibly suggested to the jury that the law required a recommendation of death; (12) the jury was misinformed of its advisory role and counsel was ineffective for failing to object; (13) the penalty phase jury instructions shifted the burden to Carroll to prove a life sentence was appropriate and counsel was ineffective in failing to object; (14) Florida's capital sentencing statute is unconstitutional; (15) the prosecutor made inflammatory and improper comments and counsel was ineffective for failing to object; (16) the sentencing court erroneously instructed the jury on the standard by which it must judge expert testimony and counsel was ineffective for failing to object; (17) the murder in course of a felony aggravator is an automatic aggravator and counsel was ineffective for failing to object; (18) the jury was misled and incorrectly informed as to its function at capital sentencing and counsel was ineffective for failing to object; (19) Carroll was incompetent during his capital pretrial, trial, and sentencing proceedings; (20) Carroll is innocent of first-degree murder and was denied an adversarial testing; (21) counsel was ineffective in failing to properly investigate and provide the mental health experts with necessary information, thereby resulting in the loss of the affirmative defense of insanity; (22) counsel failed to discover and remove prejudiced jurors; (23) newly discovered evidence shows Carroll's conviction and sentence are constitutionally unreliable; and (24) cumulative procedural and substantive errors deprived Carroll of a fair trial.

FN3. Huff v. State, 622 So.2d 982 (Fla.1993).

FN4. These claims included: claim 3 (ineffective counsel during penalty phase); claim 6—subpart A (counsel ineffective during guilt phase because he failed to provide background materials to mental health experts), and subpart C (counsel ineffective during guilt phase for failing to investigate other suspects); claim 9 (only as to counsel's alleged ineffectiveness in connection with the mental health experts); claim 19 (only as to those claims involving counsel's alleged ineffectiveness in relation to the mental health experts); and claim 21 (only as to counsel's alleged ineffectiveness in connection with the mental health experts).

3.850 APPEAL

Carroll raises eight issues on appeal, FN5 several of which may be disposed of summarily because they are procedurally barred,FN6 facially insufficient,FN7 or without merit.FN8 Carroll's remaining claims, however, warrant discussion and we will address them in turn.

FN5. These issues include: (1) the trial court erred in denying Carroll's claim that he is not guilty by reason of insanity; (2) the trial court erred in denying Carroll's claim that: (a) he was incompetent at all stages of the proceedings and trial counsel's ineffectiveness denied him a reliable competency hearing; and (b) Carroll's waiver of his right to testify and call witnesses in mitigation was not knowing, voluntary, and intelligent because he was incompetent and trial counsel was ineffective in failing to investigate mitigation; (3) the trial court erred in denying Carroll's claim that trial counsel was ineffective during the penalty phase; (4) the trial court erred in denying Carroll's claim that trial counsel was ineffective during the guilt phase; (5) Carroll was denied a full and fair evidentiary hearing; (6) the trial court erred in summarily denying: (a) Carroll's claim alleging denial of effective postconviction representation; (b) Carroll's claim alleging a violation of Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 83 S.Ct. 1194, 10 L.Ed.2d 215 (1963); (c) claims 4, 10, 12, 13, 15, 17, and 18 in Carroll's amended 3.850 motion as being procedurally barred or without merit; (d) Carroll's claim alleging that he was deprived of his right to a competent mental health expert pursuant to Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985); and (e) Carroll's claim alleging cumulative error.

FN6. We find issue (1) to be an attempt by collateral counsel to relitigate the issue of Carroll's sanity at the time of the offense. This issue could have been raised on direct appeal and thus is procedurally barred. See Harvey v. Dugger, 656 So.2d 1253, 1256 (Fla.1995). In addition, we find issue (2)(b) is procedurally barred. This issue was not asserted in Carroll's amended 3.850 motion below and thus was not addressed by the trial court. Accordingly, this issue is not properly before this Court on appeal. See Shere v. State, 742 So.2d 215, 218 n. 7 (Fla.1999); Doyle v. State, 526 So.2d 909, 911 (Fla.1988).

FN7. In issue (6)(c), Carroll alleges that the trial court erred in summarily denying claims 4, 10, 12, 13, 15, 17, and 18 in his amended 3.850 motion as being procedurally barred or without merit. On appeal, however, Carroll fails to assert any definitive argument as to this issue. Thus, we find this issue is insufficiently presented for review. See Shere v. State, 742 So.2d 215, 217 n. 6 (Fla.1999).

FN8. We find that issues (5), (6)(a), and (6)(e) are without merit. In issue (5), Carroll argues that he was denied a full and fair evidentiary hearing because the trial court allegedly prevented collateral counsel from fully questioning Detective Latrelle regarding Detective Payne's investigative notes and the trial court denied collateral counsel's motion for an extension of time to submit written closing argument. Based upon our review of the record, we conclude that this issue is without merit.

Likewise, we find Carroll's allegation in issue (6)(a) that the trial court erred in summarily denying his claim that he is being denied his right to effective representation because CCRC lacks sufficient funds is without merit. This Court has held that claims of ineffective assistance of postconviction counsel do not present a valid basis for relief. See Lambrix v. State, 698 So.2d 247, 248 (Fla.1996). Moreover, the record reflects that the trial court granted Carroll's motion for continuance requesting the court to continue the evidentiary hearing because of collateral counsel's alleged lack of funding. Although Carroll alleges that funds for hiring experts were inadequate, he does not point to any specific expert he was unable to retain as a result of under-funding. Carroll's conclusory assertion within this issue that public records were not provided to counsel or, if received, were incomplete is insufficiently pled. Moreover, the record reveals that the trial court held several hearings as to Carroll's public records requests and expressly concluded that all matters relating to his requests had been settled.

Lastly, given our resolution of the issues raised by Carroll on appeal, we find no merit to Carroll's cumulative error claim raised in issue (6)(e). See Downs v. State, 740 So.2d 506, 509 (Fla.1999).

INEFFECTIVE ASSISTANCE OF COUNSEL

First, Carroll alleges that abundant psychiatric testimony before, during, and since trial establishes that he was incompetent at the time of trial. Carroll's underlying claim that he was incompetent to stand trial should have been raised on direct appeal and therefore is procedurally barred. See Patton v. State, 784 So.2d 380, 393 (Fla.2000); Johnston v. Dugger, 583 So.2d 657, 659 (Fla.1991). As a corollary to the substantive competency claim, however, Carroll argues that trial counsel's ineffectiveness deprived him of a reliable competency hearing.

In this case, trial counsel filed a motion for a competency hearing on August 15, 1991. Thereafter, the trial court appointed Drs. Gutman and Danziger to evaluate Carroll for competency and sanity. In addition, the trial court requested Drs. Kirkland, Erlich, and Benson, who had previously evaluated Carroll for competency in November December of 1990, to re-evaluate Carroll for competency and sanity. On November 15, 1991, the trial court held a competency hearing at which Drs. Gutman, Danziger, Kirkland, and Benson testified. FN9 Of these four doctors, Dr. Benson was the only one to testify that Carroll was incompetent to stand trial.FN10 On December*611 27, 1991, the trial court entered an order finding Carroll competent to stand trial based upon consideration of the expert testimony and argument of counsel at the competency hearing, as well as the experts' reports submitted to the court.

FN9. The record reveals that Dr. Erlich did not re-examine Carroll pursuant to the trial court's order, nor did he attend the competency hearing despite being subpoenaed. In his initial report evaluating Carroll in December 1990, however, Dr. Erlich concluded that Carroll was competent to stand trial and that he believed much of Carroll's mental symptomatology was self-serving distortions.

FN10. Dr. Kirkland, who first examined Carroll in November of 1990, originally concluded that Carroll was incompetent to stand trial on a murder charge. Based on his re-examination of Carroll in October of 1991, however, Dr. Kirkland testified at the competency hearing that he believed Carroll was competent to proceed.

Nonetheless, Carroll argues that trial counsel's ineffectiveness in failing to provide adequate background information to the doctors deprived him of a reliable competency determination. Carroll alleges that Drs. Danziger and Gutman testified at the evidentiary hearing that based on additional background information supplied by collateral counsel, consisting of school records and affidavits from family members, they would reconsider their original opinions regarding Carroll's competency at the time of trial. The record, however, refutes Carroll's claim. Neither Dr. Danziger nor Dr. Gutman testified that in light of the additional background information provided by collateral counsel they would have found Carroll incompetent to stand trial. Thus, even assuming trial counsel was deficient for failing to provide the additional background information, Carroll has not demonstrated prejudice under Strickland. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 694, 104 S.Ct. 2052. Accordingly, we find this claim was properly rejected.

Guilt Phase

Carroll also asserts that the trial court erred in denying his claim alleging that trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance during the guilt phase. Specifically, Carroll argues trial counsel was ineffective in presenting an insanity defense; trial counsel was ineffective in failing to retain a confidential DNA expert; and trial counsel was ineffective in failing to impeach the testimony of the medical expert. First, Carroll maintains that the failure of his insanity defense is directly related to trial counsel's ineffectiveness. In particular, Carroll contends that: (1) trial counsel did virtually nothing to affirmatively present an insanity defense; and (2) trial counsel allowed the State to present damaging testimony from experts who based their opinions on incomplete information.

We find that the record refutes Carroll's allegation that trial counsel did “virtually nothing” to affirmatively present an insanity defense. First, trial counsel called several lay witnesses to testify at trial in support of Carroll's insanity defense. In particular, trial counsel called the director of the halfway house in which Carroll was residing at the time of the offense. She testified that Carroll began to act differently a couple of weeks before the alleged offense and that she spoke with him about getting counseling. Additionally, trial counsel called two bartenders from the taverns Carroll patronized the night before the victim was discovered. Both bartenders testified that they witnessed Carroll acting strangely and observed him talking to his jacket and speaking about demons and Satan.

More importantly, trial counsel called several mental health experts in support of Carroll's insanity defense. Dr. McMahon, who had examined Carroll within two days of the offense, testified that she observed Carroll to be extremely disorganized and only partially oriented. In her clinical opinion, Carroll was psychotic at the time of her interview, experiencing both auditory and visual hallucinations. Dr. Danziger testified at trial that he had three separate diagnoses for Carroll: schizophrenia *612 chronic differentiated type; alcoholism; and multiple drug abuse. Further, Dr. Danziger testified that more likely than not Carroll was not responsible for his actions and was so psychotic at the time of the offense that he was unable to distinguish right from wrong, although he conceded it was a difficult call. Dr. Benson testified that his diagnosis was paranoid schizophrenia, poly-substance abuse, and borderline intelligence quotient. In addition, Dr. Benson testified that Carroll was most likely actively psychotic at the time of the alleged crime and therefore did not know what he was doing or its consequences. FN11 Hence, the record clearly refutes Carroll's allegation that trial counsel did virtually nothing to present an insanity defense. FN11. By contrast, Dr. Kirkland testified for the State that he believed Carroll was not insane at the time of the offense.

Carroll also asserts that trial counsel's ineffectiveness in failing to provide adequate records and background information to the various medical experts permitted the State to portray Carroll as a malingerer, thereby weakening his insanity defense. Specifically, Carroll contends Dr. Gutman's trial testimony, that he believed Carroll was malingering and that Carroll had an IQ around 105–110, was devastating to the defense. Carroll maintains that had trial counsel provided Dr. Gutman with the additional information collateral counsel collected he would have testified favorably for the defense and deprived the State of its argument that Carroll was a calculating killer who feigned mental illness to avoid responsibility. In support, Carroll argues that at the evidentiary hearing Dr. Gutman admitted that after reviewing the additional information provided by collateral counsel his current diagnosis would be “mental disorder with mood, memory, personality change and cognitive decline associated with alcohol deterioration and influence on the brain.” FN12 Dr. Gutman also noted that the records would confirm that Carroll had evidence of a psychotic illness on or around the time of the alleged offense and that psychosis had developed.

FN12. Dr. Gutman's initial diagnosis was as follows: malingering; psychosexual disorder, pedophilia (provisional); and mixed personality disorder with antisocial passive-aggressive, paranoid and borderline personality traits.

Carroll, however, overlooks the fact that Dr. Gutman admitted at trial that his opinion regarding Carroll's IQ was inconsistent with psychological test records he had received, which showed Carroll's IQ ranging between sixty to sixty-nine and the high seventies to low eighties. Further, Dr. Gutman specifically stated at trial that he was not able to reach a conclusion regarding Carroll's sanity at the time of the offense. In fact, Dr. Gutman conceded that he was not rendering an opinion as to Carroll's mental condition at the time of the offense. Even with the additional information collected by collateral counsel, Dr. Gutman acknowledged at the evidentiary hearing that it was a close call as to whether the two statutory mental mitigating circumstances existed. Cf. Ferguson v. State, 593 So.2d 508, 511 (Fla.1992) (noting that standard for finding two statutory mental mitigators was lower than M'Naghten insanity standard). Dr. Gutman also reiterated that Carroll has a “malingering-like persona” and that his diagnosis of malingering would still be present.FN13 Thus, even if we were to assume *613 trial counsel was deficient for failing to provide the additional background information, we conclude based on the record in this case that Carroll has failed to demonstrate prejudice. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 694, 104 S.Ct. 2052. Accordingly, we find no error in the trial court's denial of this claim.

FN13. It is worth noting that Dr. Gutman was not the only expert at trial to indicate that Carroll may have been malingering. For instance, Dr. Kirkland testified that some elements of the psychological testing performed at his request shortly after Carroll's arrest indicated that he was malingering. Although Dr. Kirkland believed Carroll's symptoms of schizophrenia were genuine, he testified that he thought Carroll's claims of amnesia concerning many important events were not accurate.

Carroll also claims that trial counsel was ineffective during the guilt phase for failing to retain a confidential DNA expert. At the evidentiary hearing, however, Carroll's trial counsel testified that he made an informed tactical decision not to hire a DNA expert since at the time he thought it would have done a disservice to Carroll.FN14 In particular, trial counsel testified:

FN14. Trial counsel did speak with several DNA experts in preparation for dealing with the DNA evidence and did seek to exclude the DNA evidence during trial. On appeal, this Court denied Carroll's contention that the trial court erred in denying his motions with respect to the propriety of the DNA testing, noting that defense counsel was permitted to voir dire and extensively cross-examine the State's DNA expert. See Carroll, 636 So.2d at 1319.

I thought the DNA evidence, if it was admissible, was pretty solid.... This was an F.B.I. Lab that was under no scrutiny at the time. I thought there was a real good chance that, I kind of liked what I saw with the DNA evidence that we had. If you looked at some of the probes they looked like it wasn't—kind of hard to follow his testimony. I didn't think he was, really, that that was not totally strong. There was some areas where he said I can't be sure about this.... [I]f the judge said okay, I'm going to give you another DNA [expert], at the time I thought I would have really done Elmer Carroll a disservice....

In light of trial counsel's testimony at the evidentiary hearing, we find no error in the trial court's conclusion that counsel's decision not to retain a DNA expert was strategic and not “outside the broad range of reasonably competent performance under prevailing professional standards.” Maxwell v. Wainwright, 490 So.2d 927, 932 (Fla.1986) (citing Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984), and Downs v. State, 453 So.2d 1102 (Fla.1984)); cf. Jones v. State, 732 So.2d 313, 320 (Fla.1999) (holding that trial counsel was not ineffective for failing to obtain an expert to discuss effects of HIV and resulting AIDS). More importantly, even assuming trial counsel was deficient for failing to retain a DNA expert, Carroll has not demonstrated prejudice under Strickland. Carroll does not allege that the DNA evidence was inaccurate, nor does he assert that hiring a DNA expert would have uncovered any favorable evidence. Rather, Carroll merely contends that trial counsel's failure to procure a DNA expert constitutes ineffective assistance. Accordingly, we find no error in the trial court's denial of this claim.

Lastly, Carroll argues that trial counsel was ineffective during the guilt phase for acquiescing in the admission of autopsy photographs and failing to impeach the testimony of the medical examiner. We find the record refutes Carroll's claim that trial counsel acquiesced in the admission of autopsy photographs. Indeed, trial counsel objected to the majority of the photographs introduced during the medical examiner's testimony, on grounds that particular photographs were either prejudicial or duplicative. Further, even assuming trial counsel was deficient, we find that Carroll has failed to demonstrate prejudice under Strickland. We also find *614 Carroll's allegation that trial counsel was ineffective for failing to impeach the medical examiner is insufficiently pled. Carroll does not allege what, if any, favorable information could have been elicited by a more vigorous cross-examination of the medical examiner. Accordingly, we find no error in the trial court's denial of this claim.

Penalty Phase

Carroll argues that trial counsel was ineffective for failing to adequately investigate and present available evidence in support of statutory and nonstatutory mitigating circumstances at the penalty phase. Carroll contends that had trial counsel performed an adequate investigation substantial mitigation could have been established, including: Carroll committed the offense under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance; Carroll's capacity to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or conform his conduct to the requirements of law was substantially impaired; Carroll suffers organic brain damage; Carroll is borderline retarded; Carroll suffers from a psychotic illness; Carroll has learning disabilities and lacks mental flexibility; contributing factors of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome exist; Carroll has a long history of alcohol and drug abuse; Carroll suffered severe physical abuse as a child, including blows to the head; Carroll suffered sexual abuse as a child; and Carroll has a possible genetically conditioned mental illness.