29th murderer executed in U.S. in 2004

914th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

5th murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2004

74th murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

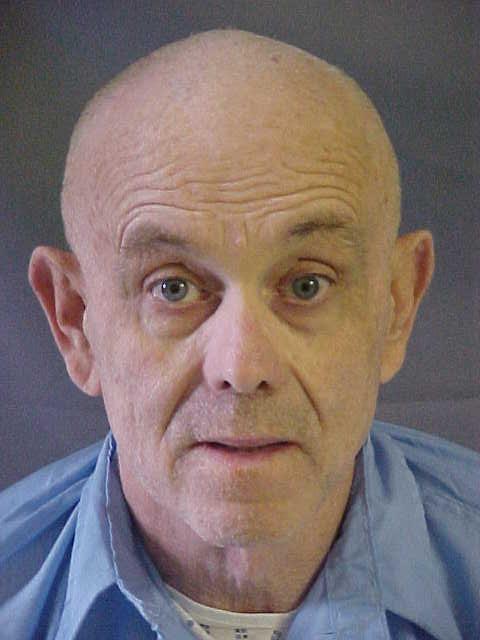

Robert Leroy Bryan W / M / 52 - 63 |

Mildred Inabell Bryan W / F / 69 |

Summary:

Robert Bryan's aunt, 69 year old Inabell Bryan, disappeared Sept. 10, 1993, and was found six days later near a combine on the property of Robert Bryan's parents near Elk City. She was found shot once in the forehead with a .22 caliber rifle. Robert Bryan was arrested after a .22 caliber shell was discovered under the front seat of a rental car he used the day of the murder. Bryan was also found to have been drawing money from Mildred Bryan's bank account after her death. Inabell Bryan did not know her nephew well, although he lived only 25 miles away. Witnesses testified that shortly before the murder, Leroy Bryan wrote agreements and promissory notes and filled out checks to withdraw money from Inabell Bryan's checking account. She signed some of the checks, and he forged her signature at least once on a promissory note for $1,800. At the time of the crime, Bryan was in his fifties, suffered from severe diabetes, and lived with his parents at their family farm.

Citations:

Bryan v. State, 935 P.2d 338 (Okl.Cr. 1997) (Direct Appeal).

Bryan v. State, 948 P.2d 1230 (Okl.Cr.App. 1997) (Postconviction).

Bryan v. Mullin, 335 F.3d 1207 (10th Cir. Okla. 2003) (Habeas).

Final Meal:

10 pieces of fried chicken, barbecue beans, cole slaw, potatoes and gravy, two biscuits and two liters of Dr. Pepper.

Final Words:

"I have been on death row for some time. I've made peace with my maker. I'll be leaving here shortly. I hope I'll see you on the other side. Until then, so long."

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: Robert L. Bryan

ODOC#: 192262

OSBI#: 650182

FBI#: 595853X1

Birthdate: 12/08/1940

Race: White

Sex: Male

Height: 6 ft. 0 in.

Weight: 170 pounds

Hair: Gray

Eyes: Blue

County of Conviction: BECKHAM

Location: Oklahoma State Penitentiary, Mcalester

Oklahoma Attorney General News Release

04/14/04 News Release - W.A. Drew Edmondson, Attorney General

Execution Date Set for Bryan

Execution Date Set for Bryan The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals today set June 8 as the execution date for Beckham County death row inmate Robert Leroy Bryan. Attorney General Drew Edmondson requested the date April 6 after the United States Supreme Court denied Bryan's final appeal. Bryan, 63, was convicted and sentenced to death for the Sept. 11, 1993, murder of his aunt, Mildred Inabell Bryan, 69. Mildred Bryan was found shot once in the forehead with a .22 caliber rifle on the property adjoining her Elk City home. Robert Bryan was arrested after a .22 caliber shell was discovered under the front seat of a rental car he used the day of the murder. Bryan was also found to have been drawing money from Mildred Bryan's bank account after her death.

Robert Leroy Bryan was convicted and sentenced to death for the Sept. 11, 1993, murder of his aunt, Mildred Inabell Bryan, 69. Mildred Bryan was found shot once in the forehead with a .22 caliber rifle on the property adjoining her Elk City home. Robert Bryan was arrested after a .22 caliber shell was discovered under the front seat of a rental car he used the day of the murder. Bryan was also found to have been drawing money from Mildred Bryan's bank account after her death.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Robert Bryan, OK - June 8, 6 PM CST

The state of Oklahoma is scheduled to execute Robert Leroy Bryan, a white man, June 8 for the 1993 murder of Inabel Bryan in Beckham County. Court records state that Mr. Bryan suffers from irreversible brain pathology, chronic paranoid schizophrenia, and organic delusional disorder.

Mr. Bryan had been charged with solicitation of murder several years previous to this crime, but was found incompetent and subsequently institutionalized. As is often the case as state mental health budgets are slashed, Mr. Bryan was treated and then released without a plan to monitor his mental health. When his illness manifested itself again, he killed his Aunt Inabel, whom he believed owed him several million dollars from cheating him out of fictional monies owed for fictional inventions.

Mr. Bryan’s organic brain damage and delusions prevented him from assisting in his defense. He worked with two court-appointed lawyers and an indigent-defense lawyer before his elderly parents mortgaged their house to hire a trial lawyer who, in the words of an appellate judge, “provided the most ineffective defense I have ever seen…” On appeal, the first three attorneys explained the difficulties in attempting to communicate with Mr. Bryan: “At times he appeared delusional, would ramble, appeared agitated, and would exhibit apparent paranoia through bizarre discourses concerning attorneys, bankers, jailers, and even a judge, all of whom, Mr. Bryan believed, were out to get him.” The state initially offered a sentence of life without parole, but Mr. Bryan’s trial lawyer advised against it. Mr. Bryan and his family forbade the use of any psychiatric evidence.

10th Circuit judges Henry, Seymour, Ebel and Lucero signed a dissenting opinion, writing “…the record shows that Mr. Bryan’s counsel clearly did not even understand that the mental health evidence might have been used in an attempt to reduce culpability at sentencing. Case law and common sense make clear that counsel’s reliance on directions from a deeply disturbed client such as Mr. Bryan cannot insulate him from his duty to present mitigating evidence.” They also criticized counsel’s failure to advise the Bryans of the life-saving value of this evidence. The dissent went on to say, “Mr. Freeman’s failure during the sentencing stage to introduce evidence that Mr. Bryan – who had been found incompetent to stand trial for a previous crime – had a long and difficult battle with mental illness, a battle made all the more difficult by disabling diabetes, no doubt caused prejudice to the defendant… “Our Constitution does not permit us to sentence this man to death without at least allowing a jury to consider evidence of his diseased mind.”

While no jury has heard evidence pertaining to Mr. Bryan’s mental illness, a judge ordered a retroactive competency hearing over a year after he was sentenced to death. Jurors at this hearing were aware of his conviction, and Mr. Bryan was forced to wear his orange inmate’s jumpsuit throughout the proceedings. At the competency hearing, two mental health experts testified that he had been procedurally incompetent at trial. All four of Mr. Bryan’s previous defense attorneys testified that he was unable to assist them because of irrational beliefs.

A state expert spent one hour with Mr. Bryan, one year prior to trial, and testified to his competency. However, this expert did not read Mr. Bryan’s complete medical records, including information about his institutionalization and diagnoses, or his record of treatment. The expert acknowledged that Mr. Bryan’s delusional disorder might be so well integrated that he would not have been able to discern it during his brief evaluation.

Mr. Bryan’s trial lawyer also failed to provide any individual portrayal of Mr. Bryan’s life, a portrayal that might have included testimony about his being a college graduate, a high school teacher, a man who was married and who began to suffer headaches, which signaled the onset of his debilitating organic brain damage.

A 2003 Human Rights Watch report found that there are three times as many mentally ill in prison as there are in psychiatric hospitals. It was clear to authorities and doctors that Mr. Bryan had violent tendencies when his schizophrenic delusions went untreated. However, he was released without any follow-up treatment. It should come as no shock that his mental illness perpetuated this pattern of violence; it is only shocking that he will now be executed for it.

Please take a moment and contact Gov. Brad Henry and urge him to stop the execution of Robert Leroy Bryan. Please further urge him to declare a moratorium on executions, and support crucial crime-prevention legislation that provides real mental health services to those who are in desperate need.

"Robert Bryan executed for 1993 killing of his aunt," by Doug Russell. (Wednesday June 9, 2004)

Wilma Wykoffe wiped tears from her eyes. "I didn't understand most of what he said," she said to no one in particular as she walked by the four windows above five rows of cinder blocks that separated witnesses from the execution chamber of Oklahoma State Penitentiary. "I did hear him say he'd made peace with his maker." Wykoffe, joined by her husband and four others, had just witnessed her brother's execution. Robert Leroy Bryan was pronounced dead at 7:24 p.m. Tuesday, less than 45 minutes after the U.S. Supreme Court turned down a request for a stay of execution.

Bryan, 63, had argued that he was incompetent to be executed; an argument turned down earlier in the day by a federal district judge and the U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Convicted of killing his aunt, Mildred Inabell Bryan, in 1993, Bryan had hinged his last hopes to avoid execution on a claim that he did not understand why he was to be executed. However, U.S. District Judge David L. Russell found that Bryan did understand and was therefore eligible for execution - the same finding reached by the federal appeals court and the Supreme Court later in the day. The nation's high court delayed the execution, initially scheduled for 6 p.m., for an hour as it considered Bryan's claim. That delay caused some consternation to Mildred Bryan's family members, who had traveled to OSP to witness the execution. "I had trouble thinking of him as a person because of what he put my mother through," said Linda Daley, Mildred Bryan's daughter.

Daley's mother had last been seen on Sept. 11, 1993. Her body was found Sept. 16 in a field near Robert Bryan's home; a pillowcase over her head. She'd been shot between the eyes. Robert Bryan was "my father's nephew," Daley said, adding that the inmate's family hadn't been close to the rest of the Bryan clan since the 1950s. The inmate was a diabetic described by many who knew him as a "manipulator" who used his illness to gain sympathy. Jan Warren, the deputy district attorney who prosecuted Bryan at trial, said during his clemency hearing, "Have you heard the term sociopath? Mr. Bryan is the closest thing to a sociopath I've ever seen."

As he lay on the gurney in the state's execution chamber, Bryan never looked toward the room in which his sister and brother-in-law, attorney Bob Nance, four reporters and others sat - much less at the one-way glass that shielded 12 of Mildred Bryan's family members and friends from view. With his head facing OSP Warden Mike Mullin, most of Bryan's last words were unintelligible, but witnesses clearly heard him say "I have been on death row for some time. I've made peace with my maker. "I'll be leaving here shortly. "I hope I'll see you on the other side. Until then, so long."

As Wykoffe sobbed against her husband's shoulder, Bryan's abdomen rose one time before he gave a loud snort. Three minutes later he was pronounced dead. "I feel like a chapter in my family's life can go on now," Daley said. "We can think more about our mother than the monster. Š It will be nice to know we don't have to look to any more procedures in the legal system."

Robert Bryan was the fifth Oklahoma inmate executed this year. For his last meal, he requested 10 pieces of fried chicken, barbecue beans, cole slaw, potatoes and gravy, two biscuits and two liters of Dr. Pepper.

"Federal court turns down death row inmate's final appeal," by April Marciszewski . (June 9, 2004)

McALESTER, Oklahoma (AP) -- Two families waited and counted down the hours until Robert Leroy Bryan's scheduled execution Tuesday night. In Mustang, Bryan's sister, Wilma Wyckoff, considered whether her 63-year-old brother understood death by lethal injection. In Benton, Ark., Linda Daley remembered with pain the murder of her mother, Mildred Inabell Bryan of Sweetwater, and hoped Leroy Bryan would get the death sentence a jury handed him nine and a half years ago.

Leroy Bryan's last attempt to get out of the death penalty failed Tuesday. The U.S. District Court in Oklahoma City denied Bryan's civil rights complaint that claimed he was not competent to be executed. Bryan was convicted of shooting his aunt in the forehead and killing her in September 1993. Wyckoff had hoped a last-minute appeal will give her brother another chance at life, or possibly to persuade a court to rehear his case. "I've gotten to the point where I'm (thinking), 'God, your will be done,'" said Wyckoff, who could also see the benefits of execution for a man who is suffering serious medical problems, including adult-onset diabetes. Her brother wouldn't have to continue to live without one leg, without urinary or bowel control or with somewhat numb arms. "He said, 'Maybe this (execution) would be a blessing. I was just hoping I could get my name cleared,'" Wyckoff said after spending about three hours with her brother Monday afternoon.

If Bryan had gotten life in prison, Wyckoff thought he would have stayed in a mental ward. If he had gotten out of the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, she thought he would have stayed in a nursing home. Wyckoff doesn't think Bryan would have liked either option. Daley hopes the execution goes on as planned, although she said it will give her little closure. "There will never really be true closure because of the premeditation and brutality," Daley said.

Inabell Bryan, 69, disappeared Sept. 10, 1993, and was found Sept. 16, 1993, near a combine on the property of Leroy Bryan's parents near Elk City. "We've always wondered what she was put through: if she was tortured, if she was fed or if she was just left out in the field," Daley said. "We think she was taken to a field and held hostage for the entire time before she was murdered."

Inabell Bryan and Leroy Bryan did not know each other well, witnesses said at his 1995 trial in Beckham County District Court in western Oklahoma. Witnesses testified that shortly before the murder, Leroy Bryan wrote agreements and promissory notes and filled out checks to withdraw money from Inabell Bryan's checking account. She signed some of the checks, and he forged her signature at least once on a promissory note for $1,800. Leroy Bryan "tried to force her to sign over everything she and Daddy had worked so hard for," Daley wrote in a letter to the Pardon and Parole Board on May 10.

Daley and about a dozen of Inabell Bryan's relatives planned to attend the scheduled execution. Wyckoff and other relatives of Leroy Bryan also planned to go. For his last meal on Tuesday afternoon, Bryan asked for 10 pieces of fried chicken, barbecue beans, cole slaw, potatoes and gravy, two biscuits and two liters of Dr. Pepper, said Jerry Massie, Oklahoma Department of Corrections spokesman.

"Bryan Executed For 1993 Murder; Courts Reject Civil Rights Complaint, Stay Request." (June 8, 2004)

OKLAHOMA CITY -- A man who was convicted in 1995 of killing his aunt was put to death Tuesday at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Robert Leroy Bryan was pronounced dead at 7:24 p.m., three minutes after receiving a lethal mixture of drugs.

His execution, originally scheduled to begin at 6 p.m., was delayed until the U.S. Supreme Court could rule on his attorney's petition and application for a stay of execution. The nation's high court denied the requests at 6:46 p.m. CDT. The U.S. District Court in Oklahoma City and the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals earlier in the day denied Bryan's legal complaint that was filed on grounds that he wasn't competent to be executed. On Monday, the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied an appeal, and the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board rejected Bryan's clemency bid on May 20.

Strapped to a gurney, Bryan kept his head turned away from a row of windows so witnesses could not see his face. Much of his last statement was unintelligible, although he spoke of legal proceedings. "I've been on death row for some time," he said. "I made peace with my maker. I will be leaving here shortly. I hope I'll see you on the other side. Until then, so long."

Bryan's chest moved up and down several times as the drugs were administered. His sister, Wilma Wyckoff, sniffled quietly and leaned on her husband's shoulder as they watched the execution. After Bryan was pronounced dead, Wyckoff told her husband, two of Bryan's friends, a minister and an attorney, "He and Nanny (another relative) are probably hugging each other's neck."

A Beckham County jury convicted Bryan, 63, of fatally shooting Mildred Inabell Bryan of Sweetwater in September 1993. Witnesses testified that shortly before the murder, Leroy Bryan wrote agreements and promissory notes and filled out checks to withdraw money from Inabell Bryan's checking account. She signed some of the checks, and he forged her signature at least once on a promissory note for $1,800. Witnesses also said Leroy Bryan and Inabell Bryan, 69, didn't know each other well. Inabell Bryan's son, Charles Bryan, wrote to the parole board on May 9 that Leroy Bryan's father fought with his brothers and alienated his family from the rest of the Bryans. "We had not visited or had anything to do with Leroy's family for well over 30 years, even though we only lived 25 miles away," Charles Bryan, of Edmond, wrote. However, Charles Bryan, Inabell Bryan and Leroy Bryan had all seen each other and talked at a family reunion months before Inabell Bryan's murder. "He was so nice, questioning me about my mother and my work," Charles Bryan wrote. "This makes me feel guilty to this very day about anything I might have said without thought."

Charles Bryan; Inabell Bryan's daughter, Linda Daley; and 12 other family members and friends of Inabell Bryan witnessed the execution. They attended to try to gain closure, "if there is such a thing," Charles Bryan said. Daley, of Benton, Ark., said she thought of Leroy Bryan more as a "monster" than as a person.

Inabell Bryan disappeared Sept. 10, 1993, and was found Sept. 16, 1993, near a combine on property near Elk City belonging to Leroy Bryan's parents. The family always wondered what happened in those days, Daley said. "She was almost on death row herself for several days," Daley said. The family hoped Leroy Bryan would admit responsibility Tuesday night for the murder, Daley said. "It was obvious that he didn't think he was the one responsible for the crime," she said.

For his last meal, Bryan requested 10 pieces of fried chicken, barbecue beans, cole slaw, potatoes and gravy, two biscuits and two liters of Dr. Pepper, said Corrections Department spokesman Jerry Massie.

Bryan v. State, 935 P.2d 338 (Okl.Cr. 1997) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the District Court, Beckham County, Charles L. Goodwin, J., of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Chapel, P.J., held that: (1) defendant's due process rights were not violated by competency proceedings; (2) letters defendant wrote to jail and court officials while incarcerated before trial were not admissible, but error in admitting such letters was harmless; (3) defendant was not in custody so as to trigger Miranda protections when police officers questioned him concerning his aunt's disappearance and murder; (4) defendant's consent to search of his home was voluntary; (5) affidavit established probable cause to search defendant's home for his aunt's promissory notes, checks, and business records; (6) venue was proper; (7) trial judge was not required to recuse himself; (8) evidence concerning defendant's previous conviction for solicitation of murder was admissible to show plan, scheme, or design; (9) prosecutor improperly commented on defendant's failure to testify, but such error was harmless; (10) hair analyst's testimony that hair found in defendant's rental car was consistent with victim's hair was admissible; (11) witness' testimony that, approximately a year before the murder, defendant attempted to hire him to dig three feet by six feet by four feet holes on some farm property was irrelevant to support continuing threat aggravating circumstance, but error in admitting such testimony was harmless; (12) lawyer's testimony that, four years before the murder, after he had successfully represented client in civil suit against defendant, defendant walked up and down sidewalk in front of his office every day for two or three months was irrelevant to support continuing threat aggravating circumstance, but error in admitting such testimony was harmless; (13) evidence of tampering by unknown persons on farm land, three and five years before the murder, was not relevant to any issue during sentencing phase, but error in admitting such evidence was harmless; (14) defense counsel was not ineffective for failing to introduce evidence of mental illness; and (15) evidence in aggravation was sufficient to support death sentence. Affirmed. Lumpkin, J., concurred in result.

CHAPEL, Presiding Judge:

Robert Leroy Bryan was tried by a jury and convicted of Murder in the First Degree in violation of 21 O.S.1991, § 701.7(A) , in the District Court of Beckham County, Case No. CF-93-61. The jury found that Bryan (1) was previously convicted of a felony involving the use or threat of violence, and (2) probably would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society. In accordance with the jury's recommendation, the Honorable Charles L. Goodwin sentenced Bryan to death. Bryan has perfected his appeal of this conviction and raises nineteen propositions of error.

Bryan was convicted of killing his elderly aunt, Inabel Bryan. At the time of the crime, Bryan was in his fifties, suffered from severe diabetes, and lived with his parents at their family farm in Beckham County. Around September 6, 1993, Bryan arranged to rent a Lincoln Town Car. Bryan specifically requested a car with a large trunk. He rented the car on September 8. Around 2:30 p.m. on Saturday, September 11, Bryan bought a distinctive lavender chrysanthemum plant at the Elk City Homeland grocery store. That evening a bystander helped Bryan change a tire on the Lincoln and saw a .22 rifle in the trunk. When Bryan returned the Lincoln on September 13, it had a .22 bullet near the driver's seat and grass and weeds stuck in the undercarriage. Bryan could not pay for the car on the 13th, but showed the dealership manager a check for $1680 made out to him by his aunt Inabel. He paid for the car the following day. Bryan and his family agreed that they seldom spoke to Inabel, had not seen her since July 17, 1993, and did not have business dealings with her.

According to the last entry in her diary, on September 11 Inabel woke at her house near Sweetwater in Roger Mills County, did chores, visited with friends, fixed and ate her lunch, studied her Sunday School lesson, picked up the mail, and took a nap. Her daughter, Linda Daley, became alarmed when she could not reach Inabel by telephone on either September 12 or 13. At the children's request Inabel's neighbor, Don Walker, went to her house twice in the late evening of September 13. Walker found that two throw rugs were disturbed, the living room curtains were open, the bed was unmade and Inabel was not there. He and his wife looked around the outbuildings, in closets and under beds. The next morning Walker returned and found Inabel's suitcase and a small overnight case containing medicines. Inabel's children, neighbors and law enforcement officials began the first of several searches of the area. Inabel's open diary was found near her reading chair, along with her open Bible and church attendance card filled out for Sunday, September 12. Daley noticed a fresh lavender chrysanthemum plant with no card on a table near the front door.

On September 16, Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation (OSBI) and FBI agents searched a section of land adjoining the Bryan family farm. Inabel's body was found lying next to a combine in a stand of trees approximately a quarter mile from the Bryan house. Her head was covered with a stained pillowcase, and duct tape was loosely wrapped around her neck. A towel lay across one leg. She had been shot once in the forehead. Subsequent searches of the site revealed more duct tape, what appeared to be a tape-and-cloth gag, a Homeland floral receipt dated September 11, and a large mushroom with a tire track imprint. During the search agents talked to Bryan, his mother and father; after the body was found the family consented to a search of their house and outbuildings. The house and field were searched again on September 17. Items found in the house included a .22 rifle with several boxes of shells, several expended shells, a pair of Bryan's overalls with a spent .22 shell casing in the pocket, a roll of duct tape matching tape found at the crime scene, and several blank checks. Also found were checks bearing Inabel's signature made out to Bryan on her account, and many handwritten documents detailing business agreements between Inabel and Bryan in which Inabel agreed to pay Bryan or assign him property.

* * * *

In accordance with 21 O.S.1991, § 701.13(C), we must determine (1) whether the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor, and (2) whether the evidence supports the jury's finding of aggravating circumstances. Upon review of the record, we cannot say the sentence of death was imposed because the jury was influenced by passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor contrary to 21 O.S.1991, § 701.13(C).

The jury was instructed on and found the existence of two aggravating circumstances: Bryan (1) was previously convicted of a felony involving the use or threat of violence, and (2) probably would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society. Upon our review of the record, we find the sentence of death to be factually substantiated and appropriate. Finding no error warranting modification, the judgment and sentence of the District Court of Beckham County is AFFIRMED.

Bryan v. State, 948 P.2d 1230 (Okl.Cr.App. 1997) (Postconviction).

Defendant was convicted in the District Court, Beckham County, Charles L. Goodwin, J., of first-degree malice aforethought murder, and sentenced to death. The Court of Criminal Appeals, 935 P.2d 338, affirmed, and defendant applied for postconviction relief. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Chapel, P.J., held that: (1) relief claims based on ineffective assistance were procedurally barred, and (2) defendant was not entitled to evidentiary hearing. Application for postconviction relief denied. Lumpkin, J., filed opinion concurring in result. Lane, J., concurred in result.

CHAPEL, Presiding Judge:

Robert Leroy Bryan was tried by jury before the Honorable Charles L. Goodwin in the District Court of Beckham County. In Case No. CF-93-61 he was convicted of First Degree Malice Aforethought Murder in violation of 21 O.S.1991, § 701.7 . At the conclusion of the first stage of trial, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. During sentencing, the jury found (1) Bryan was previously convicted of a felony involving the use or threat of violence to the person; and (2) there was a probability that Bryan would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society. Bryan was sentenced to death for the murder conviction. Bryan appealed his judgments and sentences to this Court and we affirmed. [FN1] This Court denied Bryan's petition for rehearing. The United States Supreme Court has not yet ruled on Bryan's petition for certiorari, filed September 7, 1997. [FN2]

Bryan v. Mullin, 335 F.3d 1207 (10th Cir. Okla. 2003) (Habeas).

Following state conviction for first-degree murder and sentence of death, affirmed 935 P.2d 338, petition for federal habeas relief was brought. The United States District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, David L. Russell, J., denied petition. On appeal, the Court of Appeals, 276 F.3d 1163, affirmed. On rehearing en banc, the Court of Appeals, Murphy, Circuit Judge, held that: (1) district court properly granted petitioner an evidentiary hearing on his ineffective assistance of counsel claim; (2) trial counsel lacked the medical evidence necessary to present a viable insanity defense under Oklahoma law; (3) counsel's failure to present, at guilt stage of trial, evidence of petitioner's mental illness in support of either an insanity defense or second-degree murder instruction, was not deficient performance as required to establish an ineffective assistance of counsel claim; and (4) counsel's strategic decision not to present, at penalty stage of trial, evidence of petitioner's mental illness, was reasonable when viewed from counsel's perspective at the time of the trial, and therefore was not deficient performance as required to establish an ineffective assistance of counsel claim. Vacated in part and affirmed in part. Henry, Circuit Judge, filed opinion, concurring in part and dissenting in part, in which Seymour, Ebel, and Lucero, Circuit Judges, joined.

A. Factual Background

The evidence presented at trial linking Bryan to the murder of his aunt, Inabel Bryan, was almost entirely circumstantial. Inabel disappeared from her home in September of 1993. A neighbor found tire marks at Inabel's home matching the tracks of a car Bryan had rented at that time. A potted plant was also found at Inabel's home; Bryan purchased that plant the day Inabel disappeared. Police found Inabel's body, and a receipt for the purchase of the plant, several days after her disappearance on a parcel of property owned by Bryan's parents. Inabel died from a gunshot wound to the forehead; a pillowcase was duct-taped over her head. There was a single set of vehicle tracks present at the scene; the tracks matched the tread pattern of the right rear tire on Bryan's rental car.

Authorities searched the property where Inabel's body was found because, several years earlier, Bryan had solicited an undercover police officer to kidnap and kill a local banker and dump the body at the same location. This solicitation scheme included plans to force the banker to sign a number of fraudulent promissory notes and personal checks. Similarly, in this case, Bryan possessed several handwritten promissory notes and agreements in which Inabel purportedly agreed she owed him millions of dollars as a result of an investment in his failed businesses. A handwriting expert testified Bryan wrote the agreements and forged Inabel's signature. Police also found in Bryan's possession several of Inabel's personal checks. According to the expert, Bryan had forged Inabel's signature on one of the checks and had made four others signed by Inabel payable to himself in varying amounts. Police found Inabel's checkbook just outside the Bryan home, burned in a can of ashes.

Before Inabel's disappearance, Bryan rented a car from a local dealership. When making the arrangements, he requested a car with a large trunk. When he returned the car two days after Inabel's disappearance, he could not pay the rental fee. He did, however, show the owner of the dealership one of the forged checks. Police found a hair in the trunk similar to the hair of the victim. They also found grass and vegetation, like that on the property where Inabel's body was discovered, throughout the car's undercarriage. Fibers lining the trunk were similar to those on Inabel's clothes and tape found on or near her body.

Police located additional evidence in Bryan's bedroom tying Bryan to the murder. They discovered a roll of duct tape of the same type as pieces found near Inabel's body and on the pillowcase over her head. An expert testified that the edges of the tape taken from Bryan's bedroom matched the edges of one of the pieces of tape near Inabel's body. Police also found ammunition in Bryan's bedroom consistent with the type of ammunition used to kill Inabel and consistent with a bullet in the rental car. A metallurgy study indicated that all the bullets--the one that killed Inabel, the one in the rental car, and the ones in the Bryan home--were manufactured at the same time and could have come from the same box.

B. Additional Background

The issues before this court turn on evidence of Bryan's mental health at the time of the murder and the non-use of that evidence during both the guilt and penalty phases of Bryan's trial. As a consequence, some brief additional background is in order.

Bryan has a history of organic brain disease, possibly related to his severe case of diabetes mellitus, dating back to his mid-twenties. In 1989, when Bryan was forty-nine-years-old, he was charged with solicitation of murder relating to the scheme to kidnap and kill the banker described above. He was initially found incompetent to stand trial and was sent to Eastern State Hospital in March of 1989 for treatment. Bryan was diagnosed as suffering from an organic delusional disorder and was considered severely psychotic at the time of his admission to the hospital. Doctors also discovered that Bryan's brain exhibited significant signs of atrophy. Doctors treated Bryan's diabetes and medicated him with Navane, an antipsychotic drug, until Bryan was determined competent in 1990.

After Bryan was charged in 1993 with Inabel's murder, Bryan's family hired Raymond Munkres to represent Bryan. At the arraignment, Munkres expressed serious doubt as to Bryan's competency and made an oral motion for a competency determination. A jury trial on the question of Bryan's competency was eventually held on December 30, 1993. Because it was beyond the financial resources of Bryan's family, Munkres did not present any medical testimony at the hearing. Instead, Munkres adduced the testimony of Mike Jackson, an individual who volunteered his services to Munkres as an investigator. The essence of Munkres' presentation at the competency hearing was that Bryan was incompetent because the version of events he described surrounding the murder had no basis in reality, but that Bryan nonetheless sincerely believed in the veracity of his version of events. The jury concluded that Bryan had failed to demonstrate that he was incompetent to undergo further criminal proceedings.

This competency hearing failed to comply with the dictates of the United States Supreme Court's decision in Cooper v. Oklahoma, 517 U.S. 348, 116 S.Ct. 1373, 134 L.Ed.2d 498 (1996) , because Bryan was required to prove his incompetence to stand trial by clear and convincing evidence. See Bryan I, 935 P.2d at 347. Accordingly, a retrospective competency hearing was conducted in 1996 utilizing the proper preponderance-of-the-evidence standard; Bryan was also found competent during this proceeding. See id.; Bryan III, 276 F.3d at 1168-72.

On January 3, 1994, just four days after the competency trial was completed, Bryan filed a letter with the trial court indicating as follows: "I wish to advise the court that as [of] this date I am dismissing my attorney of record because of philosophical differences in how this case should proceed in my best and most aggressive defense to the charges leveled against me." The trial court allowed Munkres to withdraw from the case and appointed the Oklahoma Indigent Defense System ("OIDS") to represent Bryan.

Wesley Gibson of the OIDS replaced Munkres as Bryan's attorney. Like Munkres, Gibson could not verify Bryan's version of the events surrounding the murder. Gibson hired Dr. J.R. Smith, a board-certified psychiatrist, to evaluate Bryan. It was Dr. Smith's opinion that Bryan's "delusional system and circumstantiality of thought (as well as the fluctuating blood sugar levels) affect his ability to assist his attorney in his own defense. He produces volumes of information that are irrelevant and often erroneous (but believed by the patient)." Based on the information provided by Dr. Smith, Gibson requested a second competency hearing. At a hearing on the application, the trial court considered the testimony of Gibson and the sheriff in charge of the jail where Bryan was housed, as well as the affidavit of Dr. Smith. The trial court denied the application for a new competency hearing, concluding that there was no doubt that Bryan was then competent.

Gibson continued to represent Bryan until May of 1994, when he had a slight stroke. He was replaced by Steven Hess, also of the OIDS. Hess continued to consult medical experts and hired Dr. Philip Murphy, a clinical psychologist, to evaluate Bryan. Based on an evaluation which included numerous psychological tests and a review of relevant medical records, Dr. Murphy concluded as follows: "Mr. Bryan suffers from a serious mental disorder which places into serious question his competence to stand trial, as well as his legal culpability in the crimes for which he is charged."

Based on the opinions expressed by Drs. Smith and Murphy, and the two unsuccessful attempts to challenge Bryan's competency, Hess thought it was in Bryan's best interest to utilize an insanity defense rather than to continue to litigate the competency issue. Accordingly, Hess filed a notice of intent to rely on the insanity defense and a witness list setting out expert witnesses, including particularly Drs. Smith and Murphy, in support of such a defense. When Hess informed Bryan and his parents that he intended to utilize an insanity defense, both Bryan and his parents expressed their disapproval. Shortly thereafter, Bryan and his parents informed Hess that he would be replaced by privately retained counsel. In so doing, they indicated that Hess was being replaced because he had filed the notice to rely on an insanity defense.

Hess was replaced by Jack Freeman. Freeman contacted Hess and indicated that he would be Hess' replacement. He also set up a meeting with Hess and the medical experts. Hess turned over Bryan's file to Freeman, including all of the records and expert reports on Bryan's mental health. Freeman did not ultimately present any mental health evidence during either the guilt or penalty phase of Bryan's trial, although he arranged for Dr. Murphy to be available in case his testimony would be helpful during the guilt phase of the trial.

* * * *

IV. CONCLUSION

This court cannot say, under the facts set out above, that Freeman's strategic choice not to present mental health evidence during Bryan's trial was objectively unreasonable. "There are countless ways to provide effective assistance in any given case." Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689, 104 S.Ct. 2052; We are mindful that it is "all too easy for a court, examining counsel's defense after it has proved unsuccessful, to conclude that a particular act or omission of counsel was unreasonable." Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689, 104 S.Ct. 2052. Thus, "in considering claims of ineffective assistance of counsel, we address not what is prudent or [even] appropriate, but only what is constitutionally compelled." Burger v. Kemp, 483 U.S. 776, 794, 107 S.Ct. 3114, 97 L.Ed.2d 638 (1987) (quotation omitted). In this case, Bryan has failed to establish that "in light of all the circumstances, [counsel's] identified acts or omissions were outside the wide range of professionally competent assistance." Strickland, 466 U.S. at 690, 104 S.Ct. 2052

HENRY , J., concurring in part and dissenting in part; Judges SEYMOUR, EBEL , and LUCERO, join.