16th murderer executed in U.S. in 2004

901st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2004

72nd murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

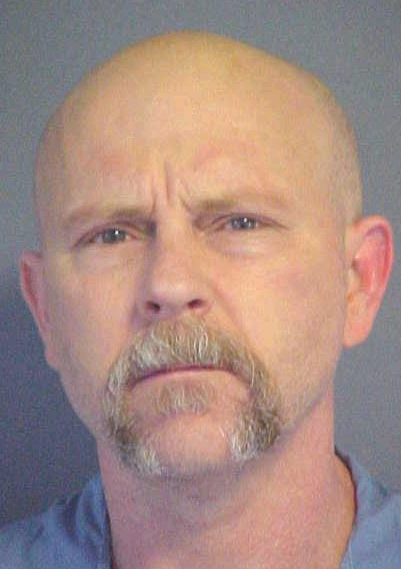

David Jay Brown W / M / 33 - 49 |

Eldon Lee McGuire W / M / 47 |

Summary:

David Jay Brown's stormy relationship with his ex-wife and her family was punctuated by intimidation, threats and violence which culminated in the death of his former father-in-law, Eldon Lee McGuire. McGuire was repeatedly shot inside his home in Grady County in February 1988. Brown was married to Lee Ann McGuire for about 6 months in 1983. Their breakup was followed by years of family conflict in which Brown often made threats against the McGuire family. In 1986, Brown walked into a hair-styling shop his ex-wife owned armed with a rifle and held 12 people hostage before firing the weapon into a vacant barber chair. He was charged with kidnapping and pointing a weapon. Brown somehow got out of jail on bond and fled. He resurfaced a year later, again threatening the family to dismiss the charges. Brown was arrested two weeks after the murder in Louisville, Kentucky. He had admitted to friends that he "had it out" with Eldon. Following his arrest, Brown claimed self-defense after Eldon had invited him into the home. A lever-action rifle was found in the middle of the room and one shot had been fired from it. Brown fled the scene following the shooting, which left McGuire with 8 bullet wounds, two in the head which were delivered at close range.

Citations:

Brown v. State, 871 P.2d 56 (Okl.Cr. 1994) (Direct Appeal).

Brown v. Oklahoma, 115 S.Ct. 517 (1994) (Cert. Denied).

Brown v. State, 933 P.2d 316 (Okl.Cr. 1997) (PCR).

Brown v. Gibson, 7 Fed.Appx. 894 (10th Cir. 2001) (Habeas).

Brown v. Gibson, 122 S.Ct. 650 (2001) (Cert. Denied).

In Re Brown, 122 S.Ct. 2652 (2002) (Stay).

Final Meal:

Barbecue beef with hot sauce and onion, two large orders of french fries and a vanilla malt.

Final Words:

"All I want to know is . . . I want to tell ya'll people that the state and federal courts that works on our cases, specifically on our appeals, are nothing but a bunch of morons. Specifically, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals and the US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. My records prove this. That's it. Let's go."

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: David Jay Brown

ODOC#: 176151

OSBI#: 376748

FBI#: 521020L11

Birthdate: 03/30/1954

Race: White

Sex: Male

Height: 5 ft. 8 in.

Weight: 140 pounds

Hair: Brown

Eyes: Green

County of Conviction: GRADY

Location: Oklahoma State Penitentiary, Mcalester

"Oklahoma Killer Calls Courts 'Morons' Before His Execution." (March 9, 2004)

McAlester, Okla. - Last June, David Brown was six hours away from the death house when an appeals court blocked his execution. He wasn't as lucky Tuesday night. With his last ditch appeals rejected, Brown was put to death by lethal injection for the murder of his former father-in-law. He became the third condemned killer executed in Oklahoma this year.

But he didn't go out without calling the courts a "bunch of morons." "All I want to know is... I want to tell ya'll people that the state and federal courts that works on our cases, specifically on our appeals, are nothing but a bunch of morons, " Brown said in his last statement. "Specifically, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals and the US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. My records prove this. That's it. Let's go." The lethal dose of chemicals began at 6:04 p.m. and Brown was declared dead at 6:07 p.m.

Claims Self Defense

The murder occurred in 1988, but Brown had claimed that he shot his former father-in-law, Eldon McGuire in self defense. Brown had come within six hours of execution last June when the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals granted him a stay. Documents in a 10th Circuit Court of Appeals decision denying Brown's appeal revealed that Brown had gone to McGuire's home. Brown claimed that when he went inside, McGuire, who had previously shot him, attacked him and then pulled a gun and fired at him. He said he pulled his own gun and fired back - 18 times. Two of the shots hit McGuire, one in the head from close range, the court documents stated.

Marriage Gone Wrong

The shooting of McGuire was an ugly culmination of a stormy marriage Brown had with his McGuire's daughter. The court documents say that Brown had been arrested and faced 150 years in prison after he went to the beauty salon where his ex-wife worked. He had a rifle and kept patrons hostage. He was arrested and charged with 16 criminal counts, including 12 counts of kidnapping. Following the arrest, Brown somehow got out of jail on bond and fled. He resurfaced a year later. The court documents stated that the only aggravating factor prosecutors had to show in order to convince a jury to sentence Brown to death was on his "future dangerousness."

Puppy Killing Used Against Him

In his appeals, Brown has cited ineffective assistance of trial and appeals counsel. He claims the lawyers did not do enough to offer mitigating circumstances that would have saved him from a death sentence. These factors including alcoholism, drug abuse, an unstable family environment while growing up and the fact that his former father-in-law had shot and wounded him in 1983. His appeals lawyers also cited instances of alleged prosecutorial misconduct. In once instance, prosecutors elicited testimony at his trial that Brown once became enraged when a puppy urinated on the floor and shot and killed the canine.

Oklahoma Attorney General News Release

01/06/04 News Release - W.A. Drew Edmondson, Attorney General

Execution Date Set for Brown

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals today set March 9 as the execution date for Grady County death row inmate David Jay Brown, Attorney General Drew Edmondson said. Brown was convicted of the Feb. 19, 1988, murder of his ex-father-in-law, Eldon Lee McGuire, 47, in Norge, Okla. Brown shot McGuire eight times, twice in the head. This is Brown's fourth execution date.

On Dec. 3, 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Brown's final appeal. On Jan. 8, 2002, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals set a Feb. 5, 2002, execution date. Brown later asked that his attorneys be allowed to withdraw. Judge Wayne F. Alley granted that request and entered a stay of execution in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma. Brown's new attorney then asked to file a second and successive habeas petition. That request was denied April 23, 2002, by the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Attorney General Edmondson that day asked the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to set an execution date. On May 6, 2002, the court set a second execution date for June 25, 2002. At a June 11, 2002, clemency hearing, the Pardon and Parole Board voted to recommend clemency. Gov. Frank Keating denied clemency June 18, 2002.

On June 21, 2002, Brown filed an emergency request for a stay of execution, a second application for post-conviction relief and a request for an evidentiary hearing claiming trial error. On July 17, 2002, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals issued a stay of execution. On March 25, 2003, a third application for post conviction relief was filed, and on March 26 the Court of Criminal Appeals granted the request for an evidentiary hearing and remanded the case to Grady County District Court. The District Court found no trial error and returned the case to the Court of Criminal Appeals. After briefing by both parties, the Court of Criminal Appeals today formally denied the request for post conviction relief and set the execution date.

There are currently two other Oklahoma inmates scheduled for execution: Tyrone Peter Darks, Cleveland County, Jan. 13 and Norman Richard Cleary, Tulsa County, Feb. 17. Oklahoma County death row inmate Hung Thanh Le received a 30-day stay of execution Dec. 17 after the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommended clemency at a Dec. 9 hearing.

Brown and his ex-wife, Lee Ann McGuire, had a short, stormy marriage surrounded by a generally tempestuous relationship. Eldon , Lee Ann's father, never approved of the relationship, and did not like Brown, nor did Brown like him. The situation became more serious when at one point after the marriage was terminated, Brown walked into the hair styling shop where Lee Ann worked. He was carrying a rifle, and during an argument with Lee Ann fired the weapon into a vacant barber chair. There were several people in the shop at the time. Brown was arrested and charged with several criminal counts as a result of the incident. Brown thought the charges were manufactured by Eldon, who was a retired captain with the Chickasha Fire Department and who Brown believed was very influential with law enforcement officers. Believing the charges were bogus charges and believing he would get a long prison term, Brown absconded while on bail and fled the jurisdiction. A little over a year later, Brown returned to the area. He did not surrender to authorities, but called Lee Ann to see if she would consent to dismissing the charges. She refused. He became angry, telling Lee Ann he had left a message in the wood pile at her parent's house and they would all be sorry. An obscene message was found in the woodpile. In addition, he accurately described to Lee Ann the actions of her and her parents at the house on a particular night, indicating he had been watching the house.

Brown and Eldon had at least one previous physical confrontation. Brown had also called Eldon's house less than a month before the homicide. As Eldon's wife picked up an extension, she heard Brown tell Eldon "you all's time is up," and they would pay for what they had done to him. A friend of Brown's talked with Brown a month or two before the homicide. Brown blamed Eldon for his legal troubles, believing Eldon wielded undue influence over Lee Ann. When the friend asked Brown if there was anything he could do to help, Brown asked the friend to beat up Eldon. In the context of the conversation, the friend did not know whether Brown was serious. Brown's ex-wife, Connie, heard Brown say he would like to beat up Eldon.

Testimony showed he possessed a handgun at the time he made the statement and seemed frustrated at the time he made the statement. Jerry Clark, a man Brown met while he was outside Oklahoma, returned temporarily with Brown to the area in January and February 1988. During this period, he heard Brown say he would like to get intoxicated and kill Eldon, as he had cost Brown everything he owned. Brown also said he did not care if the whole family were dead. Clark returned to Louisville, Kentucky, on February 16. Brown returned there on February 21, a Sunday. Brown told Clark he and Eldon "had it out" and Brown got even. He said he had gone to Eldon's house, and left him on the floor.

When they first arrived in January, Brown and Clark acquired a room in an El Reno motel, where they stayed for approximately a week. El Reno is north of Chickasha approximately 40 miles. Brown checked back into the same motel on February 16. Although he paid for the room through February 23, he left the motel on February 19, the day of the homicide, and did not return. Brown admitted going to Eldon's house, claiming he did so to convince him to change his mind about the charges. He claims Eldon allowed him to enter the house, then hit him from behind, knocking him down. He said Eldon then kicked him and told him he would kill him. At one point Eldon kicked at Brown and missed, striking the bedroom door. Brown said as he ran for the front door to exit the house, Eldon fired a shot at him, at which time Brown pulled from his back pocket a loaded 9 mm. semiautomatic pistol and began firing blindly at Eldon. He said he fired until the gun was empty, firing approximately 18 times in two or three seconds. He then went back to the motel for his clothes, then drove to Louisville.

Authorities found Eldon partially curled up in front of his bathroom and near a wall heater on the south end of his living room. They found heel marks on a bedroom door across the room, and paint matching that on the door on Eldon's boot heel. They found several 9 mm. casings around the living room sofa and others in other spots around the room. Three slugs were found in the open: one on the floor near a chair, one between Eldon's feet and one on some nearby clothing. There were nine bullets in the lower portion of the wall behind the body similar to the ones lying in the open. In the northeast corner of the living room authorities found embedded in a wall a copper-jacketed bullet and fragment not consistent with the others found. That path where that bullet was found was consistent with an entry and exit hole in the corner of a television set and a shattered oil lamp globe which had been standing next to the television. A lever-action rifle was found in the middle of the room; one shot had been fired from it. The lever action was partially pulled down, but not far enough to eject the spent casing in the chamber. Four live, copper-jacketed rounds were found inside the rifle. Blood was also found on the rifle, as was a small dent, as if something had ricocheted off the rifle.

Eldon suffered a severe gunshot injury to the index, middle and ring finger of his left hand which in the opinion of the medical examiner would have rendered him incapable of using it. A man's gold ring was found in the living room; it had been badly damaged. The medical examiner found seven additional gunshot wounds to the body and two to the head. A wound on the left shoulder bore evidence of stippling, indicating the weapon causing the injury was fired at intermediate range. A firearms expert with the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation performed tests on a handgun taken from Brown, and concluded the weapon would have left stippling if it were fired from a distance of less than 30 inches. Both entry wounds in the head indicated shots had been fired from relatively close range. One was surrounded by stippling, indicating intermediate range. The other wound had gunpowder residue inside the wound itself. The medical examiner concluded this could only come from a "hard contact wound," meaning the barrel was pressed against the scalp itself when the weapon was fired. Brown testified he got no closer than two or three feet from Eldon during the brief struggle.

The position of the bullets found at the scene disproves Brown's self-defense theory. Despite Brown's claims he shot Eldon only to preserve his own life and did not intend to kill him, he did not seek help for Eldon after the shooting. Instead, he ran out the door, apparently locking it behind him. He testified on direct examination he took the weapon with him because he did not know what would transpire at the house; however, he said on cross-examination he intended to use the weapon if he had to. Despite Brown's claim he did not get closer than two feet to Eldon while firing, one head wound shows the gun barrel was pressed against Eldon's head when the gun was fired. Most of the bullet holes were fired into the west wall and corner of the short hallway. Photographs of the scene show that the corner of the hallway cannot be seen from the front door area, as it is blocked by a wall heater, which did not exhibit any signs of being fired at. It is apparent from the evidence that if Brown had been running toward the door while firing as he claimed, his line of fire would have been blocked by this wall heater, which would have blocked the bullets found in the lower wall behind the body.

The murder of Eldon McGuire was discovered on February 20, 1988, when his daughter Lee Ann McGuire, received word he could not be contacted by telephone. Eldon had telephoned his wife, who was a patient in a local hospital, between 7:30 and 7:45 the evening before. He told her he was tired and would visit her the next morning. Lee Ann and Eldon's mother arrived at his house, forced entry through the front door, and discovered his body lying in the south end of the living room. Authorities found a cordless telephone in the kitchen area. They also found in the kitchen some meat and cheese unwrapped and uneaten; it appeared that Eldon was preparing to eat his evening meal. Brown was arrested in Louisville, Kentucky, on March 3, 1988.

UPDATE: David Jay Brown's stormy relationship with his ex-wife and her family was punctuated by intimidation, threats and violence - violence that culminated in the death of his former father-in-law. Brown, 49, is scheduled to be executed by a lethal dose of drugs for the Feb. 19, 1988, murder of Eldon Lee McGuire, who was repeatedly shot inside his home in Norge in Grady County. Brown, whose Feb and June 2002 execution dates were stayed by federal judges, was married to McGuire's daughter, Lee Ann, for about 6 months in 1983. Their breakup was followed by years of family conflict in which Brown often made threats against the McGuire family, prosecutors said. At one point, he walked into a hair-styling shop his ex-wife owned armed with a rifle and held 12 people hostage before firing the weapon into a vacant barber chair. He was charged with kidnapping and pointing a weapon. "This is a person who definitely deserves the ultimate punishment," said Grady County assistant district attorney Bret Burns, whose office prosecuted the case. "He planned and executed a cold-blooded murder," Burns said. "He's not somebody that we want living amongst us." Brown has admitted shooting McGuire but claims he acted in self defense. Prosecutors say Brown's self-defense argument is not believable because McGuire was shot eight times, including two in the head at close range. "That defeats any claim of self defense," Assistant Attorney General Sandy Howard said.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

David Jay Brown, Oklahoma - March 9, 6 PM CST

The state of Oklahoma is scheduled to execute David Jay Brown, a white man, March 9 for the 1988 death of his former father-in-law, Eldon McGuire, in Grady county. In 2002 the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted to grant him clemency. Unfortunately this decision has been ignored by former Gov. Frank Keating and current Gov. Brad Henry.

David Jay Brown and Lee Ann McGuire were involved in a short, stormy marriage surrounded by a generally tempestuous relationship. Mr. Brown blamed the victim, Mr. McGuire, for many of the problems in his marriage. Approximately one year previous to Mr. McGuire’s murder, Mr. Brown had entered a barbershop brandishing a gun, threatened his estranged wife, and fired a gunshot into an empty chair. He was charged with several counts, which he believed to be manufactured by Mr. McGuire who was influential with the town’s law-enforcement. He skipped bail and left town.

If Mr. Brown’s trial counsel had interviewed his family, they would have discovered that his mother was a prostitute and a severe alcoholic who married four abusive men by the time he was 12 years old. As a child he was left to protect his mother and siblings from these men, and began to use drugs and alcohol at a young age.

Because of the gross inadequacy of Mr. Brown’s defense, and in light of the mitigating evidence that was never heard by a jury, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted to grant clemency. In two cases, after the former governor denied clemency, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals granted relief. In one of these cases, Gerardo Valdez, a Mexican national, was granted a new sentencing hearing and subsequently received a life sentence.

It is clear that executive clemency in Oklahoma is not a ''fail- safe'' option if courts have had to step in even after the clemency decision has been made. In addition, it is unclear what the purpose of the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board is in capital cases, if its recommendations for clemency are routinely rejected.

Please contact Gov. Henry and urge him to follow the Board’s recommendation. If a man is executed after receiving such a sub-par defense at the hands of the state, a true injustice will have occurred.

"Killer to Die Tonight," by Doug Russell. (March 9, 2004)

For the second time, a man who killed his ex-father-in-law is scheduled to be the third inmate of the year to be executed.

David Jay Brown is scheduled to die at 6 tonight by lethal injection at Oklahoma State Penitentiary.

It's the fourth execution date that has been scheduled for Brown, and the second time he was scheduled to be the third inmate of the year executed.

The 49-year-old inmate, who says he was defending himself when he fired the shots that killed 47-year-old Eldon Lee McGuire, a Norge rancher and fire captain.

Brown and McGuire's daughter, Lee Ann, had a stormy six-month marriage in 1983, but the storms didn't stop with their breakup. Following the marriage, Brown continued to harass and threaten the McGuire family, according to prosecutors.

According to Brown, he had gone to McGuire's home on Feb. 19, 1988, to try to talk with McGuire. Brown claims he was invited inside and then knocked to the floor, after which McGuire fired a rifle at him.

"I just went to his house to talk to him," Brown said in a previous interview with the News-Capital & Democrat. He added that he'd carried a semi-automatic 9 mm pistol with him "just in case."

"Maybe I shouldn't have taken a gun with me," Brown said. "If I hadn't, I wouldn't be sitting here. I wouldn't be sitting anywhere."

The case has a long and convoluted history. Brown's final appeal was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court in December 2001 and the OCCA set a Feb. 2, 2002 execution date.

A federal judge stopped the execution to allow for a new round of appeals, using new attorneys, but the federal 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ended the stay of execution in April 2002.

A new execution date was set for June 25, 2002. Two weeks before the scheduled execution, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted to recommend clemency for Brown. Governor Frank Keating denied clemency on June 18 and the date of execution drew closer.

Another stay of execution was filed when Brown's attorneys asked for an evidentiary hearing, claiming that prosecutors had wrongfully withheld information from defense attorneys at Brown's initial trial. That stopped the execution indefinitely as the OCCA mulled over the matter. Then the court voted to grant a stay of execution and the case was sent back to Grady County for an evidentiary hearing.

Once the hearing was over, the case was returned to the OCCA for action, Grady County Prosecutors said.

That action was setting Brown's fourth execution date.

"Brown Executed for Killing Ex-father-in-law," by April Marciszewski. (AP March 9, 2004)

McALESTER, Okla. - David Jay Brown criticized appeals courts just before the state of Oklahoma put him to death Tuesday for the 1988 murder of his former wife's father.

"I want to tell y'all people that the state and federal courts that works on our cases, specifically on our appeals, are nothing but a bunch of morons, specifically the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals and the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals," Brown, 49, said in a final statement. "My records prove this."

Just 19 minutes before his scheduled execution, the U.S. Supreme Court denied a request filed Monday by attorney Gary Peterson to review Brown's case, the last of a series of appeals.

Brown was convicted in the Feb. 19, 1988, murder of his ex-father-in-law, 47-year-old Eldon McGuire. He spent 15 years on Oklahoma's death row.

Before the execution at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary began, the lawyers Brown had invited as witnesses filed silently into the room. Accordion-style blinds rose, showing Brown as he lay on a gurney.

After his statement, he jerked his head to the left to see his lawyers, including Peterson, and said, "That's it. Let's go."

Brown closed his eyes and sighed deeply after the lethal injections were administered at 6:04 p.m. His chest heaved up and down several times. He was pronounced dead at 6:07 p.m.

Brown claimed in his trial and throughout his appeals that he killed McGuire in self-defense. Brown testified in Grady County District Court that he was trying to run out of McGuire's house when McGuire shot at him and he blindly shot back.

Senior Assistant Attorney General Sandy Rinehart disputed the self-defense claim, citing testimony that Brown touched his gun to the top of McGuire's head when he shot McGuire.

McGuire's only daughter, Lee Ann, and Brown were married for six stormy months in 1983 before she divorced him. Following the marriage, Brown threatened the family several times.

Two of McGuire's cousins, Allen McGuire and Jeff McGuire, witnessed the execution. Eldon McGuire's wife, Ann, and daughter, Lee Ann, were on vacation and did not see Brown die.

"The family is just really glad this is over," Allen McGuire said. "It should have been over a long time ago."

This was Brown's fourth execution date.

Allen McGuire said Brown had an easier death than Eldon McGuire.

"We think he (Brown) got what he deserved," Allen McGuire said. "We'll put it behind us and go on."

Brown's was the third execution in Oklahoma this year. For his last meal, Brown ate barbecue beef with hot sauce and onion, two large orders of french fries and a vanilla malt.

"Oklahoma inmate on death row for 15 years to be executed." (March 9, 2004)

OKLAHOMA CITY (AP) _ David Jay Brown has spent the past 15 years on death row, appealing to every court possible for his freedom. His fight is expected to end Tuesday. His execution for the death of his former father-in-law, Eldon McGuire, is scheduled for 6 p.m. at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Brown's execution has been stayed three times. The Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommended clemency in 2002, but former Gov. Frank Keating denied it. On Monday morning, Brown's attorney, Gary Peterson, asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case. Senior Assistant Attorney General Sandy Rinehart planned to file a response Tuesday morning, asking the court not to hear the case and not to stay the execution. ``He's more than exhausted all appeals,'' Rinehart said. For his last meal, Brown asked for barbecue beef with hot sauce and onion, two large orders of french fries and a vanilla malt. McGuire's family will be glad when the execution is over and they can move on, said McGuire's cousin Barbara Logue. McGuire's wife, Ann, and daughter, Lee Ann, have gone on vacation and won't be back until after the scheduled execution. ``They didn't want to be here,'' Logue said. ``It's just too painful for them. ... They just want it to be over and hope to gain some closure from this.'' The problems started with Lee Ann McGuire and Brown's stormy six-month marriage in 1983. After the marriage ended, Brown threatened the family. He and Eldon McGuire had never gotten along. In 1986, Brown showed up with a rifle at Lee Ann McGuire's hair salon in Chickasha, the Clipper Ship. ``He said, 'Don't anyone touch the phone or I'll blow you away,''' Lee Ann McGuire testified in Grady County District Court. He shot into an empty barber chair. He was charged with kidnapping the people in the shop and pointing a weapon. Brown blamed Eldon McGuire, a recently retired Chickasha Fire Department captain, for the charges. Ann McGuire testified in Grady County District Court that Brown told her husband, ``You are all going to pay. You all's time's up. You're going to pay for what you did to me.'' In February 1988, Brown checked into an El Reno motel about 40 miles north of Chickasha. He testified he went to Eldon McGuire's house to patch up their relationship, but when he arrived, McGuire hit him, kicked him and told him he would kill him. Brown said he was running to leave the house when McGuire shot at him. Brown said he shot back blindly in self-defense, a theory the prosecution disputed. ``There was a hard-contact wound,'' Rinehart said. ``The muzzle had to be against the head, which defeats any self-defense claim.'' McGuire was shot eight times, including once in the back of the head, testified Dr. Chai Choi, who performed the autopsy. Lee Ann McGuire and her grandmother Lillian McGuire found Eldon McGuire dead inside his house the next day. ``Since the death of Eldon, his daughter and wife have lived in constant turmoil,'' Logue and her brothers wrote in a statement Monday. ``Hopefully, they will be able to find some peace and go on with their lives after the execution.''

Brown v. State, 871 P.2d 56 (Okl.Cr. 1994) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the District Court, Grady County, James R. Winchester, J., of first-degree murder, and was sentenced to death. He appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Lumpkin, P.J., held that: (1) defendant's affidavit in support of application for change of venue must set forth facts rendering a fair and impartial trial there improbable; (2) trial court's failure to grant defendant change of venue was not fundamental error; (3) evidence was sufficient to support finding that defendant acted with premeditation; (4) defendant's waiver of right to be present during sentencing phase of trial was valid, and his absence was voluntary; and (5) aggravating circumstance that there was probability that defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would be continuing threat to society outweighed mitigating factors.

Affirmed.

LUMPKIN, Presiding Judge:

* * *

For his first proposition of error, Appellant claims the evidence was insufficient to show he committed the crime of first degree murder. Specifically, he claims the evidence did not show premeditation. Since this case presents both direct and circumstantial evidence, we will review it in the light most favorable to the State to determine whether any rational trier of fact could find the elements of the crime charged beyond a reasonable doubt. Spuehler v. State, 709 P.2d 202, 203-04 (Okl.Cr.1985). In reviewing this evidence, this Court must accept all reasonable inferences and credibility choices that tend to support the verdict of the trier of fact. Curtis v. State, 762 P.2d 981, 982 (Okl.Cr.1988). We find that, viewed in the light most favorable to the prosecution, the evidence is sufficient.

The evidence here indicates the death arose from an ongoing family conflict. Appellant and his ex-wife, Lee Ann McGuire, had a short, stormy marriage surrounded by a generally tempestuous relationship. The decedent, Lee Ann's father, never approved of the relationship, and did not like Appellant, nor did Appellant like him. The situation became more serious when at one point after the marriage was terminated, Appellant walked into the hair styling shop where Lee Ann worked. He was carrying a rifle, and during an argument with Lee Ann fired the weapon into a vacant barber chair. There were several people in the shop at the time. Appellant was arrested and charged with several criminal counts as a result of the incident. Appellant thought the charges were manufactured by the decedent, who was a retired captain with the Chickasha Fire Department and who Appellant believed was very influential with law enforcement officers. Believing the charges were bogus charges and believing he would get a long prison term, Appellant absconded while on bail and fled the jurisdiction.

A little over a year later, Appellant returned to the area. He did not surrender to authorities, but called Lee Ann to see if she would consent to dismissing the charges. She refused. He became angry, telling Lee Ann he had left a message in the wood pile at her parent's house and they would all be sorry. An obscene message was found in the woodpile. In addition, he accurately described to Lee Ann the actions of her and her parents at the house on a particular night, indicating he had been watching the house.

Appellant and the decedent had at least one previous physical confrontation. Appellant had also called the decedent's house less than a month before the homicide. As the decedent's wife picked up an extension, she heard Appellant tell the decedent "you all's time is up," and they would pay for what they had done to him. A friend of Appellant's talked with Appellant a month or two before the homicide. Appellant blamed the decedent for his legal troubles, believing the decedent wielded undue influence over Lee Ann. When the friend asked Appellant if there was anything he could do to help, Appellant asked the friend to beat up the decedent. In the context of the conversation, the friend did not know whether Appellant was serious. Appellant's ex-wife, Connie, heard Appellant say he would like to beat up the decedent. He possessed a handgun at the time he made the statement. He seemed frustrated at the time he made the statement.

Jerry Clark, a man Appellant met while he was outside Oklahoma, returned temporarily with Appellant to the area in January and February 1988. During this period, he heard Appellant say he would like to get intoxicated and kill the decedent, as he had cost Appellant everything he owned. Appellant also said he did not care if the whole family were dead. Clark returned to Louisville, Kentucky, on February 16. Appellant returned there on February 21, a Sunday. Appellant told Clark he and the decedent "had it out" and Appellant got even. He said he had gone to the decedent's house, and left him on the floor.

When they first arrived in January, Appellant and Clark acquired a room in an El Reno motel, where they stayed for approximately a week. El Reno is north of Chickasha approximately 40 miles. Appellant checked back into the same motel on February 16. Although he paid for the room through February 23, he left the motel on February 19, the day of the homicide, and did not return.

We believe this evidence is adequate to show premeditation. Taken in the light most favorable to the prosecution, the physical evidence at the scene negates Appellant's theory of self-defense.

Appellant admitted going to the decedent's house, claiming he did so to convince him to change his mind about the charges. He claims the decedent allowed him to enter the house, then hit him from behind, knocking him down. The decedent then kicked him and told him he would kill him. At one point the decedent kicked at Appellant and missed, striking the bedroom door. As Appellant ran for the front door to exit the house, the deceased fired a shot at him, at which time Appellant pulled from his back pocket a loaded 9 mm. semiautomatic pistol and began firing blindly at the decedent. He said he fired until the gun was empty, firing approximately 18 times in two or three seconds. [FN1] He then went back to El Reno for his clothes, then drove to Louisville.

FN1. It is important to note the pistol is a semiautomatic pistol. The firearms expert testified at trial a separate pulling on the trigger is required to fire each round (Tr. 777). We think it unlikely any normal person could fire such a weapon 18 times in two or three seconds; and in any event, a person could not simply "[freeze] down on the trigger of a semiautomatic pistol and discharge all of the rounds in the clip," as Appellant claims in his reply brief. The mechanics of the weapon make this impossible.

Authorities found the decedent partially curled up in front of his bathroom and near a wall heater on the south end of his living room. They found heel marks on a bedroom door across the room, and paint matching that on the door on the decedent's boot heel. They found several 9 mm. casings around the living room sofa and others in other spots around the room. Three slugs were found in the open: one on the floor near a chair, one between the decedent's feet and one on some nearby clothing. There were nine bullets in the lower portion of the wall behind the body similar to the ones lying in the open. In the northeast corner of the living room authorities found embedded in a wall a copper-jacketed bullet and fragment not consistent with the others found. That path where that bullet found was consistent with an entry and exit hole in the corner of a television set and a shattered oil lamp globe which had been standing next to the television. A lever-action rifle was found in the middle of the room; one shot had been fired from it. The lever action was partially pulled down, but not far enough to eject the spent casing in the chamber. Four live, copper-jacketed rounds were found inside the rifle. Blood was also found on the rifle, as was a small dent, as if something had ricochetted off the rifle.

This information is obtained from the transcript and other evidence admitted during the trial. During oral argument, Appellant used

during argument a diagram of the decedent's residence, showing the location of several items. However, since the exhibit was not admitted at trial, it was not properly before this Court, and is not being used by this Court in its deliberations.

The decedent suffered a severe gunshot injury to the index, middle and ring finger of his left hand which in the opinion of the medical examiner would have rendered him incapable of using it. A man's gold ring was found in the living room; it had been badly damaged. The medical examiner found seven additional gunshot wounds to the body and two to the head. A wound on the left shoulder bore evidence of stippling, indicating the weapon causing the injury was fired at intermediate range. A firearms expert with the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation performed tests on a handgun taken from Appellant, and concluded the weapon would have left stippling if it were fired from a distance of less than 30 inches.

Both entry wounds in the head indicated shots had been fired from relatively close range. One was surrounded by stippling, indicating intermediate range. The other wound had gunpowder residue inside the wound itself. The medical examiner concluded this could only come from a "hard contact wound," meaning the barrel was pressed against the scalp itself when the weapon was fired. Appellant testified he got no closer than two or three feet from the decedent during the brief struggle.

We believe the position of the bullets found at the scene disproves Appellant's self-defense theory. Despite Appellant's claims he shot the decedent only to preserve his own life and did not intend to kill him, he did not seek help for the decedent after the shooting. Instead, he ran out the door, apparently locking it behind him. He testified on direct examination he took the weapon with him because he did not know what would transpire at the house; however, he said on cross-examination he intended to use the weapon if he had to. Despite Appellant's claim he did not get closer than two feet to the decedent while firing, one head wound shows the gun barrel was pressed against decedent's head when the gun was fired. Most of the bullet holes were fired into the west wall and corner of the short hallway. State's exhibits 9, 10 and 11 are photographs of the scene. They show that corner of the hallway cannot be seen from the front door area, as it is blocked by a wall heater, which did not exhibit any signs of being fired at. We agree with the State that had Appellant been running toward the door while firing as he claimed he did, his line of fire would have been blocked by this wall heater, which would have blocked the bullets found in the lower wall behind the body.

We believe this evidence is sufficient. While the Court has "a duty to assess the historical facts when it is called upon to apply a constitutional standard to a conviction obtained in a [trial] court," "this inquiry does not require a court to 'ask itself whether it believes that the evidence at the trial established guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.' Instead, the relevant question is whether, after viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the prosecution, any rational trier of fact could have found the essential elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt." Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 318-19, 99 S.Ct. 2781, 2788-89, 61 L.Ed.2d 560 (1979) (citations omitted) (emphasis in original). In this light we find the evidence supports both the presence of premeditation required for first degree murder and the absence of self-defense. This first proposition is without merit.

* * *

Reviewing the evidence in mitigation and aggravation, we find the sentence of death to be factually substantiated and appropriate. Finding no error warranting reversal or modification, the judgment and sentence for Murder in the First Degree is AFFIRMED.

Brown v. State, 933 P.2d 316 (Okl.Cr. 1997) (PCR).

Following affirmance, 871 P.2d 56 of first-degree murder conviction and death sentence, petitioner sought postconviction relief. The District Court of Grady County, James R. Winchester, J., denied relief, and petitioner appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Lumpkin, J., held that: (1) several claims were waived; (2) trial defense counsel was not ineffective; (3) appellate counsel was not ineffective; (4) district court properly denied petitioner's motion for discovery; (5) district court properly decided postconviction claims without evidentiary hearing; and (6) petitioner's pro se motion for crime scene reconstruction expert was not properly before postconviction court.

Affirmed.

Strubhar, V.P.J., concurred in results.

Brown v. Gibson, 7 Fed.Appx. 894 (10th Cir. 2001) (Habeas)

Following affirmance of conviction and death sentence for first-degree murder, 871 P.2d 56, state prisoner petitioned for habeas corpus. The district court denied relief, and petitioner appealed. The Court of Appeals, Brorby, Circuit Judge, held that: (1) ineffective assistance of trial counsel was not shown; (2) state procedural bar was not adequate as to one claim; (3) ineffective assistance of appellate counsel was not established, to excuse procedural defaults; (4) argument asserting legal, not factual, innocence did not overcome procedural default; (5) prosecutor's comment on mitigating evidence did not warrant relief; (6) petitioner knowingly, voluntarily and intelligently waived the right to be present at the penalty phase of trial; (7) evidence did not require a second-degree murder instruction; and (8) determination of state appellate court that sufficient evidence existed to support the continuing threat aggravator was reasonable.

Affirmed.

BRORBY, Circuit Judge.

FACTS

In the afternoon of February 20, 1988, Mr. McGuire was discovered dead by his daughter Lee Ann McGuire and his mother Lillie McGuire. The two had gone to check on him when he could not be reached by telephone. The prior evening, he had telephoned his wife Laverne McGuire, who was in the hospital, to tell her that he would visit her the next morning, but he had failed to do so. At the time he was found, there was unwrapped meat and cheese on the kitchen table, suggesting he was preparing to eat before he was murdered.

Mr. Brown and Lee Ann had had a stormy six-month marriage and eight-year relationship. Mr. McGuire had never approved of Mr. Brown. And Mr. Brown did not like and was afraid of Mr. McGuire. Once the two had had a physical confrontation.

Sometime after the marriage had ended, Mr. Brown went to the beauty shop where Lee Ann worked, taking a rifle with him. He argued with her, told the people in the shop not to touch the telephone or he would blow them away, and shot at a vacant chair. Most people in the shop retreated to the back room. Mr. Brown was arrested and charged with sixteen criminal counts, including twelve counts of kidnaping. He thought the charges were manufactured by Mr. McGuire, who was a retired fire department captain and who Mr. Brown believed had influence with law enforcement. When the charges were not dismissed and Mr. Brown believed he could receive a greater than 150 year sentence, he fled from the area.

A little over a year later, he returned. He called Lee Ann. When she refused to have the charges dismissed, he became angry. She testified that he told her if they did not do something about the charges, they would all be sorry. Also, he described to her both her and her parents' actions on a particular night, indicating he had been watching them. He left an obscene message in the woodpile at her house. Approximately one month prior to the murder, Mr. Brown called the McGuire house. Laverne testified she picked up the telephone and heard Mr. Brown tell Mr. McGuire "you all's time" is up and they would pay for what they had done to him.

At approximately the same time, Mr. Brown told a friend he blamed Mr. McGuire for his problems. When the friend asked what he could do to help, Mr. Brown told him to beat up Mr. McGuire. Another ex-wife of Mr. Brown, Connie Brown, testified Mr. Brown said he would like to beat up Mr. McGuire. Jerry Clark, with whom Mr. Brown became acquainted after absconding, testified Mr. Brown said he would like to get drunk and get even with Mr. McGuire because he had cost him everything and he did not care if the whole bunch was dead. Mr. Clark also testified Mr. Brown told him after the murder that he had gotten even with Mr. McGuire and had left him on the floor.

At trial, Mr. Brown testified he went to the McGuire house to convince Mr. McGuire to drop the charges. According to Mr. Brown, Mr. McGuire invited him in; hit him from behind, knocking him down; kicked toward him striking a bedroom door and told him he would kill him. As Mr. Brown ran to leave the house, Mr. McGuire fired a shot. Mr. Brown then pulled a semiautomatic gun from his back pocket and fired eighteen shots in self-defense.

Mr. McGuire sustained two bullet wounds to his head. One came from a gun fired at close range, and the other was a hard contact wound. He also suffered other gunshot wounds, including a wound to his left hand, rendering him incapable of using it.

* * *

We have reviewed the record in this case and considered all of Mr. Brown's arguments on appeal, including those not specifically addressed, and are not persuaded constitutional error infected his trial. We therefore AFFIRM the district court's denial of habeas corpus relief.

Appellant David Jay Brown was tried by jury and convicted of Murder in the First Degree (21 O.S.Supp.1982, § 701.7), Case No. CRF-88-45, in the District Court of Grady County. The jury found the existence of one aggravating circumstance, the existence of a probability Appellant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society (21 O.S.1981, § 701.12(7)), and recommended death as punishment. The trial court sentenced accordingly. From this judgment and sentence Appellant has perfected this appeal. We affirm.

The murder of Eldon McGuire was discovered on February 20, 1988, when his daughter Lee Ann McGuire, received word he could not be contacted by telephone. The decedent had telephoned his wife, who was a patient in a local hospital, between 7:30 and 7:45 the evening before. He told her he was tired and would visit her the next morning. Lee Ann and Eldon's mother arrived at his house, forced entry through the front door, and discovered the decedent lying in the south end of the living room. Authorities found a cordless telephone in the kitchen area. They also found in the kitchen some meat and cheese unwrapped and uneaten; it appeared the decedent was preparing to eat his evening meal. Appellant was formerly married to Lee Ann, and blamed the decedent for a multitude of problems in his life. He was arrested in Louisville, Kentucky, on March 3, 1988. As he has alleged insufficiency of the evidence in his first proposition, the evidence will be discussed in more detail below.

David Jay Brown was convicted of the first degree murder of his former father-in-law, Eldon McGuire. The jury found the one aggravator offered, that he would be a continuing threat to society, and recommended a death sentence. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and death sentence, Brown v. State, 871 P.2d 56 (Okla.Crim.App.), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1003, 115 S.Ct. 517, 130 L.Ed.2d 423 (1994), and denied post-conviction relief, Brown v. State, 933 P.2d 316 (Okla.Crim.App.1997). Thereafter, Mr. Brown sought federal habeas corpus relief. The district court, in a very thorough and careful opinion, denied relief. Exercising jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1291, we affirm.