14th murderer executed in U.S. in 2006

1018th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in North Carolina in 2006

42nd murderer executed in North Carolina since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

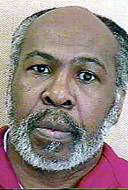

Willie Brown Jr. B / M / 38 - 61 |

Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon B / F / 29 |

Summary:

Police received a call that the Zip Mart on Main Street seemed to be open for business, but the clerk was not there. On arrival, the police confirmed that the clerk, Vallerie Ann Dixon, was missing, along with approximately $90.00 from the register and safe. Her vehicle was spotted on Highway 64 and police pulled behind with red lights and siren. The car continued at slow sppeds for several blocks. The driver was identified as Brown and immediately arrested. Inside the vehicle police found a .32 caliber six-shot revolver and a paper bag containing approximately $90.00 in cash and a small change purse containing money, identification, and other items belonging to Dixon. At the station, Brown admitted that he had walked to the Zip Mart and robbed the clerk while wearing a toboggan cap and using a .32 caliber revolver. He stated that he ordered the clerk to give him her car keys, and he proceeded to make his escape in her vehicle until being apprehended by the police. The defendant, however, denied having any knowledge of the present whereabouts of the clerk and stated that he had left her unharmed at the store. The next morning, searchers discovered the body of Ms, Dixon, shot six times, in an area consistent with the location defendant was headed away from when spotted that morning, five miles out of town.

Citations:

State v. Brown, 315 N.C. 40, 337 S.E.2d 808 (N.C. 1985) (Direct Appeal).

Brown v. Lee, 319 F.3d 162 (4th Cir. N.C. 2003) (Habeas).

Brown v. Polk, 135 Fed.Appx. 618 (4th Cir. N.C. 2005) (Unpublished) (Habeas).

Brown v. Beck, 2006 WL 1030236 (4th Cir. N.C. 2006) (Injunction).

Final Meal:

A well-done T-bone steak, rice, four rolls with butter and a piece of German chocolate cake.

Final Words:

"I love you."

Internet Sources:

BROWN, WILLIE

DOC Number: 0052205

DOB: 11/24/44

RACE: BLACK

SEX: MALE

DATE OF SENTENCING: 11/15/1983

COUNTY OF CONVICTION: MARTIN COUNTY

FILE#: 83000921

CHARGE: MURDER FIRST DEGREE (PRINCIPAL)

DATE OF CRIME: 03/06/1983

North Carolina Department of Correction (Press Releases)

Execution date set for Willie Brown Jr.

Date: March 21, 2006

RALEIGH - Correction Secretary Theodis Beck has set April 21, 2006, as the execution date for inmate Willie Brown Jr. The execution is scheduled for 2:00 a.m. at Central Prison in Raleigh.

Brown, 61, was sentenced to death November 15, 1983, in Martin County Superior Court for the murder of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon. He also received an additional 40-year sentence for robbery with a dangerous weapon.

ATTENTION EDITORS: A photo can be obtained by using the "Offender Search" function on the Department of Correction Web site at www.doc.state.nc.us. For more information about the death penalty, including selection of witnesses, click on the “Death Penalty” link.

Brown executed for 1983 murder; first to use monitor to measure inmate's level of consciousness," by Andrea Weigl. (Modified: Apr 21, 2006 05:58 AM)

RALEIGH - Convicted killer Willie Brown Jr. was executed about 2 a.m. today for the 1983 slaying of a Williamston convenience store clerk.

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal by Brown's lawyers that the state's lethal injection procedures put him at risk for a painful execution. Not long after, Gov. Mike Easley denied clemency. The state uses a three-drug cocktail to execute death row inmates: one drug to put them to sleep, a second to paralyze them and a third to stop their hearts. Citing eyewitness accounts and toxicology evidence, Brown's lawyers argued that there was a possibility that inmates were not fully sedated before the second and third drugs were injected and therefore could be awake to experience agonizing deaths.

Without comment Thursday afternoon, two federal appeals court judges on the three-judge panel affirmed U.S. District Court Judge Malcolm J. Howard's ruling that the state has proposed adequate measures to ensure Brown is unconscious before the final two drugs are injected. The state planned to have a doctor and a nurse watch a bispectral index, or BIS, monitor, that measures brain waves and ranks Brown's level of consciousness from a scale of zero to 100. The state's expert said once Brown's consciousness level dropped below 60, there was little risk that he would be conscious. Brown is thought to be the first inmate to have the BIS monitor used in his execution.

Experts had criticized the state's proposal because it requires medical professionals to participate in executions in violation of their professional ethics and their roles as caregivers. Brown's lawyers argued that the state was misusing the BIS monitor, which the manufacturer said was not intended to be used alone but rather as one piece of information among many considered by an anesthesiologist to determine whether a patient is adequately anesthetized. It was unknown, they said, whether the doctor and nurse are adequately trained to use the machine.

In a dissent, federal appeals court Judge M. Blane Michael wrote, "Brown presents an impressive array of evidence that although a BIS monitor may be helpful in assessing the effectiveness of anesthesia, it is not suitable as the state intends to use it." He concludes, "The clear weight of evidence ... reveals that the state's use of the BIS monitor will not adequately ensure that Brown will remain unconscious throughout his execution."

Brown was sentenced to death for the 1983 killing of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon, a clerk at the Zip Mart in Williamston. Dixon was taken from the store and found the same day as the robbery lying facedown along a logging road after being shot six times. Brown, who maintains his innocence, was convicted of murder and armed robbery.

For his last meal, Brown ate a well-done T-bone steak, rice, four rolls with butter and a piece of German chocolate cake.

"Appeals denied, N.C. man put to death," by Andrea Weigl. (Modified: Apr 22, 2006 03:11 AM)

RALEIGH - Convicted killer Willie Brown Jr. was executed about 2 a.m. Friday for the 1983 slaying of a Williamston convenience store clerk.

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal by Brown's attorneys that the state's lethal injection procedures put him at risk for a painful execution. Not long after, Gov. Mike Easley denied clemency. The state uses a three-drug cocktail to execute death row inmates: one drug to put them to sleep, a second to paralyze them and a third to stop their hearts.

Citing eyewitness accounts and toxicology evidence, Brown's attorneys argued that there was a possibility that inmates were not fully sedated before the second and third drugs were injected and therefore could be awake to experience agonizing deaths. Without comment Thursday afternoon, two federal appeals court judges on the three-judge panel affirmed U.S. District Court Judge Malcolm J. Howard's ruling that the state had proposed adequate measures to ensure Brown would be unconscious before the final two drugs were injected.

Brown was sentenced to death for the 1983 killing of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon, a clerk at the Zip Mart in Williamston. Dixon was taken from the store and found the same day as the robbery lying facedown along a logging road after being shot six times. Brown, who maintained his innocence, was convicted of murder and armed robbery.

For his last meal, Brown ate a well-done T-bone steak, rice, four rolls with butter and a piece of German chocolate cake.

"N.C. execution carried out with brain monitor," by Estes Thompson. (AP April 21, 2006)

RALEIGH (AP) - A North Carolina man executed Friday for the 1983 slaying of a convenience store clerk was put to death wearing a monitor to measure whether he was asleep before being injected with deadly chemicals. Willie Brown Jr., 61, was pronounced dead at 2:11 a.m. by Marvin Polk, warden of Central Prison in Raleigh. He had been sentenced to death for killing Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon.

Brown's lawyers had fought to stop the execution, saying no one could be certain that he would be asleep. A federal judge had threatened to halt the execution if the state didn't convince him that Brown could be sedated if he shows signs of awakening, but allowed the execution after the state purchased the monitor. "No additional sedation was needed before the lethal drugs were administered," said Department of Correction spokesman Keith Acree, who said a doctor and nurse watched the bispectral index monitor to be certain Brown was unconscious. It was the first time the monitor had been used in a North Carolina execution and officials said it hadn't been used in other states.

Defense lawyer Don Cowan, who watched the execution, said he "didn't see anything tonight that changed my mind. Based on what I saw, I don't know if the judge's concerns were met." Cowan had wanted to know the specific qualifications of the medical staff, but U.S. District Court Judge Malcolm Howard ruled the state's assertion that it was using a licensed doctor and nurse was sufficient. Brown had electrocardiogram leads attached to his chest and intravenous lines in his arms. He also wore the brain monitor's white, bandage-like sensor that ran from his left temple across his forehead.

Before he was injected, Brown looked into the witness room at his brother and sister, nodded and mouthed "I love you." As the chemicals were injected, Brown's chest heaved and his tongue fluttered before he lay still with his mouth open. His sister sobbed quietly. Brown's nieces, who were among two dozen relatives who came to the prison, said their uncle was innocent. "He was a person," said niece Jamie Brown of Charlotte. "He wasn't a monster."

William Dixon, husband of the victim and a witness to the execution, said in a written statement that he was satisfied with the execution and felt sorry for Brown's family. "For years, I was thinking that he was going free again to do bad things to other people," Dixon said.

As the clock ticked toward the execution, Brown lost appeal after appeal in federal courts, ending with the Supreme Court, and his clemency request was rejected by Gov. Mike Easley. Several hours before the execution, Brown had a last meal of well-done T-bone steak, rice, rolls with butter and German chocolate cake. He didn't make a last statement.

"Brown wears brain monitor as he is executed ; Judge ruled device would ensure inmate was asleep." (THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Saturday, April 22, 2006)

RALEIGH - A North Carolina man executed yesterday for the 1983 killing of a convenience-store clerk was put to death wearing a monitor to measure whether he was asleep before being injected with deadly chemicals. Willie Brown Jr., 61, was pronounced dead at 2:11 a.m. by Marvin Polk, the warden of Central Prison in Raleigh. Brown had been sentenced to death for killing Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon.

Brown's attorneys had fought to stop the execution, saying that no one could be certain that he would be asleep. A federal judge had threatened to prevent the execution if the state didn't convince him that Brown could be sedated if he showed signs of awakening, but allowed the execution after the state bought the monitor. "No additional sedation was needed before the lethal drugs were administered," said Keith Acress, a spokesman for the N.C. Department of Correction, who said that a doctor and nurse watched the bispectral index monitor to be certain Brown was unconscious. It was the first time the monitor had been used in a North Carolina execution. Defense attorney Don Cowan said he "didn't see anything tonight that changed my mind. Based on what I saw, I don't know if the judge's concerns were met."

Before he was injected, Brown looked into the witness room at his brother and sister, nodded and mouthed "I love you." As the chemicals were injected, Brown's chest heaved and his tongue fluttered before he lay still with his mouth open. His sister quietly sobbed. Brown had electrocardiogram leads attached to his chest and intravenous lines in his arms. He also wore the brain monitor's white, bandagelike sensor that ran from his left temple across his forehead.

"North Carolina Man Executed For 1983 Killing." (UPDATED: 4:35 am EDT April 21, 2006)

RALEIGH, N.C. -- Willie Brown Jr. was executed early Friday for the 1983 killing of a woman during a convenience store robbery in Martin County. He was pronounced dead at 2:11 a.m., said Keith Acree, a spokesman for the state Department of Correction. Before he died, Brown looked at his sister and appeared to mouth "I love you." The execution came after Gov. Mike Easley rejected Brown's clemency request Thursday evening and the U.S. Supreme Court and a three-judge panel of the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, Va., also ruled against him.

Brown, 61, was sentenced to death for the slaying of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon. He was sentenced in 1983 in Martin County Superior Court and received an additional 40-year sentence for armed robbery.

Brown's attorneys had argued that the death penalty is unnecessarily cruel because Brown might remain conscious and suffer pain while being put to death by injection. Before the Supreme Court, they had argued that he was poorly represented by his trial lawyer and that the judge gave erroneous instructions to the jury. At one point, his attorneys convinced a federal judge to order the state to change its procedures to ensure that condemned inmates stayed asleep during their executions.

U.S. District Court Judge Malcolm Howard said he would stop Brown's execution without such an assurance. But, he allowed the state to proceed after it agreed to bring in a brain wave monitor to measure Brown's level of consciousness and have medical personnel ready to sedate him again if necessary. A three-judge panel of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed Howard's decision in a split ruling Thursday. Judge M. Blane Michael dissented, saying the state failed to prove that the monitor by itself would be a reliable gauge of Brown's level of consciousness. Given the dissent, Brown's lawyer, Don Cowan, filed a motion asking the full court _ 14 judges _ to consider the appeal. The full appeals court denied the request.

After Brown was executed, Acree said Brown did not need any additional sedatives before the lethal drugs were administered, but Cowan said he doesn't "think we'll ever know if Judge Howard's concerns were met tonight." Brown visited with family members Thursday and Acree said Brown ordered a last meal of a well-done T-bone steak, rice, rolls with butter and German chocolate cake.

At Central Prison, about 40 people protested and eight were arrested on trespassing charges.

Willie Brown was sentenced to death in 1983 for the fatal shooting of a woman, Valerie Ann Roberson Dixon, during the robbery of the convenience where she was working. Brown forced her to get in her car and then drove Valerie to a rural area. Brown shot Valerie to death and dumped her body. He was arrested shortly after the murder, driving Valerie's car.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Willie Brown Jr., NC - April 21

Do Not Execute Willie Brown Jr.!

Willie Brown Jr., a 61-year-old black man, faces execution on April 21 for the 1983 murder of Valerie Ann Roberson Dixon. Brown is alleged to have robbed the Martin County convenience store where Dixon was working. He is said to have forced her to get in her car, which he drove to a nearby rural area. It was there that Brown is alleged to have shot Dixon to death, and left the body. Brown was apprehended while driving Dixon’s car shortly thereafter.

In his petition for a writ of habeas corpus, Brown argued that his death sentence was unconstitutional because the jurors had been instructed that any finding among them of mitigating evidence must be unanimous. Bearing this in mind, the jury failed to find any evidence of mitigation and, consequently, recommended a death sentence. Brown submitted a motion for appropriate relief, asking that his sentence be thrown out. He argued that his 8th and 14th amendment rights had been violated by the jury instructions. His motion was denied. However, four years later the U.S. Supreme Court held in McKoy v. North Carolina (1990) that the North Carolina unanimous jury instruction used in Brown’s case was unconstitutional. In light of this ruling, Brown filed another motion. Ordinarily, a retroactive application of “new rules” is not permitted except under specific circumstances: either 1) the new rule makes the initial crime non-criminal, or 2) the new rule regards a procedure so important that without it the odds of getting an accurate conviction are seriously reduced. Sure enough, the district court and the 4th circuit court of appeals held that Brown’s case failed to fit those circumstances, and could not be considered in light of McKoy.

This nonretroactivity doctrine exists to give some finality to criminal convictions. However, what is the cost of such finality? Willie Brown is simply asking that the same right granted to any person convicted of a felony offense be extended to him. He was sentenced to death using a procedure that isn’t even considered to be constitutional any more. Nonetheless, because his case falls through a legal crack, Willie Brown will be executed in April. We cannot permit this to happen.

Please write to Gov. Michael Easley on behalf of Willie Brown Jr.!

People of Faith against the Death Penalty

"Willie Brown Killed During Easter Week." (Updated April 24, 2006)

Less than a week after Easter, the people of North Carolina killed Willie Brown during the early morning Friday, April 21.

Willie Brown, Poorly Defended, Mentally Ill, Scheduled for Execution April 21

The state of North Carolina has scheduled Willie Brown to die at 2 a.m. April 21, despite his seriously inadequate representation and documented evidence of mental illness. Brown, a 61-year-old African-American man, was convicted of robbing a store and murdering the clerk, Valerie Ann Roberson Dixon. He was sentenced to death in Martin County in 1983. Brown’s execution would be immensely unfair for several reasons.

Brown has a documented history of mental illness. Concerns regarding Mr. Brown’s mental health were raised in 1963, when Brown was only nineteen years old. State records reveal several diagnoses of mental illness, including paranoid and delusional disorders, before the crime. Despite these findings, Brown never received treatment of any kind. Brown’s symptoms include anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and paranoid thoughts.

The prosecutor did not view Brown’s case as a clear death penalty case. Before trial, the prosecutor offered a plea agreement that would have removed the death penalty from consideration. Brown’s mental illness, particularly his paranoid delusions, and his attorneys’ inexperience proved to be a fatal combination when Brown refused to accept the life-saving plea offer.

Brown’s lawyers failed to present critical mitigating evidence. The jury that sentenced Brown to death did not know that Brown suffered from significant mental illness. Nor did they know that, as a child, he had been beaten by his father. Although numerous family members and friends were available and willing to testify that they loved Brown and wanted him to live, Brown’s counsel made no efforts to contact these individuals. This is the very nature of evidence that frequently sways the jury, and taken together, would have presented a compelling case for life in prison instead of death. Represented by two attorneys who had never before tried a capital case, Brown’s sentencing hearing took merely an hour; the testimony of witnesses on his behalf comprised fewer than 20 pages of transcript. A competent presentation of mercy-evoking evidence typically takes at least a day of testimony.

Brown’s appeal was unfair. At Brown’s trial, the jury was given unconstitutional instructions concerning how to weigh whether Brown should live or die. However, his trial attorney, who represented him on appeal as well, never objected to these instructions.

Because his lawyer failed to raise the issue properly, and despite the fact that close to 50 other death-sentenced prisoners had their death sentences thrown out for the very same error, no court has ever considered the effect of these unconstitutional instructions on Brown’s case. In fact, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that the State’s refusal to hear Brown’s claim was unjust compared to the cases of other North Carolina capital defendants. Brown is the only North Carolina prisoner whose jury received the flawed instruction who faces execution.

"Doctors’ oath a concern in executions; Experts: Participation breaks ‘do no harm’ vow." (Apr 21, 2006)

RALEIGH - Early today, if a doctor and nurse did what prison officials asked, experts said they would violate their professional ethics by participating in the execution of death row inmate Willie Brown Jr. Prison officials planned to have a doctor and nurse watch a bispectral index, or BIS, monitor, to make sure Brown is unconscious before he is injected with lethal drugs.

Brown, 61, who was to be executed at 2 a.m. today, is thought to be the first inmate in the country whose execution will involve such a medical device, which measures brain waves. State officials proposed using the machine this month to alleviate a federal judge’s concerns that Brown might experience a painful death. The judge then required the machine and the medical professionals’ involvement for the execution to proceed.

The code of medical ethics of both the American Medical Association and the N.C. Medical Society prohibits physicians being involved in executions, including watching a heart monitor or consulting with those people injecting the lethal drugs. And doctors take an oath to first, do no harm. "You are using medical skills in the participation of an execution," said Priscilla Ray, chairwoman of the AMA’s council on ethical and judicial affairs. North Carolina law requires a prison doctor be present at all executions and keeps doctors’ identities confidential.

Code for doctors

At the request of several local doctors, the N.C. Medical Board will discuss at its May meeting what punishment a doctor could face for participating in an execution.

Arthur Finn, a retired doctor and professor in Chapel Hill who opposes the death penalty, was one of those who wrote to the board. "If there’s a state law that says a physician has to be present, and if the medical board says it’s unethical to be present, then they’re going to have to stop executions at least until the rules are changed," Finn said.

The American Nurses Association also opposes nurses being involved in executions, but the state board has no such policy, a rarity among the nation’s licensing boards for nurses.

Brown was set to die by lethal injection for the 1983 killing of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon, a Williamston convenience store clerk. The same morning that the Zip Mart was robbed, Dixon’s body was found on the ground along a logging road with six bullet wounds. In a recent letter to The News & Observer, Brown wrote, "I am totally and completely innocent." Brown was hoping Gov. Mike Easley might grant him clemency or that a federal appeals court might give him a reprieve based on his legal challenge to the state’s method of lethal injection.

In North Carolina, a condemned inmate is given a series of three drugs: one to put him to sleep, another to paralyze him and a third to stop his heart. Brown’s attorneys had been arguing that if the first drug did not work, then Brown could experience an excruciating death, which would violate the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Victims’ advocates, however, say there is justice in killers experiencing painful deaths.

A federal judge asked state officials to come up with a proposal to lessen the chance that Brown was awake when the paralytic and heart-stopping drugs were administered. State officials purchased a BIS monitor for $5,400 and proposed having a doctor and nurse, who already were to view a heart monitor connected to the inmate, watch the BIS monitor. The execution team will continue to give a barbiturate to the inmate until the BIS monitor indicates that the inmate is adequately anesthetized, according to court records.

"N. Carolina execution raises ethical concerns; American Medical Association says doctors' role in death 'violates' oath." (Reuters Updated: 8:17 a.m. ET April 21, 2006)

RALEIGH, N.C. - A North Carolina man was executed by lethal injection Friday by officials using a machine to ensure he did not suffer undue pain, a procedure that raised ethical questions about medical staff monitoring the death. Willie Brown Jr., 61, was pronounced dead at 2:11 a.m. by Warden Marvin Polk at the state’s Central Prison, spokesman Keith Acree said. Brown had been sentenced to death for the 1983 killing of a convenience store clerk after a robbery.

Amid increased scrutiny of lethal injections across the country, a doctor and a registered nurse who routinely observe North Carolina’s executions employed a brain wave monitor to determine whether Brown was unconscious before he was injected with paralytic and heart-stopping drugs. Brown’s execution was believed to be the first in the United States using the device. State officials purchased the machine after a judge ordered North Carolina to ensure Brown felt no pain.

In other states such as Florida and California, executions have been delayed while courts ponder whether lethal injections cause excessive pain. North Carolina’s procedure, approved by U.S. District Judge Malcolm Howard, raised ethical questions for the doctor and nurse who watched over the machine from an observation room near the death chamber. The American Medical Association’s code of ethics prohibits doctors from participating in executions and views the monitoring of a brain wave machine as relying on a physician’s skill and expertise, and therefore forbidden.

'Violates' medical oath

“The use of a physician’s clinical skill and judgment for purposes other than promoting an individual’s health and welfare undermines a basic ethical foundation of medicine --first, do no harm,” said Dr. Priscilla Ray, head of the association’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs.

“Therefore, requiring physicians to be involved in executions violates their oath to protect lives and erodes public confidence in the medical profession.”

The association is not a regulatory body and cannot punish doctors.

The execution of an inmate in California was halted in February after San Quentin prison failed to find anesthesiologists willing to participate. A judge had ordered the presence of anesthesiologists to ensure the inmate’s death was painless. Brown’s lawyers argued the methods used by North Carolina and 36 other states did not fully ensure inmates were unconscious before lethal drugs were injected. If inmates were not fully sedated, they could experience an agonizing death, defense lawyers said. That could result in cruel and unusual punishment prohibited by the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, they said. Brown’s lawyers argued only medical professionals trained to administer anesthesia could ensure Brown was unconscious.

Howard ruled this week the brain wave monitor could be used instead. He also required the involvement of medical personnel for the execution to proceed. State law has long required a physician to be present at executions. Their identities are confidential by law.

More than 2,000 people were known to have been executed around the world last year, the vast majority of them in China, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United States, Amnesty International said Thursday.

State v. Brown, 315 N.C. 40, 337 S.E.2d 808 (N.C. 1985) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the Superior Court, Martin County, Donald L. Smith, J., of first-degree murder and robbery with a dangerous weapon, and death sentence was imposed for murder conviction. Defendant appealed as a matter of right. The Supreme Court, Meyer, J., held that: (1) failure to conduct arraignment on capital charge did not constitute reversible error per se, and defendant was not prejudiced by lack of arraignment; (2) evidence of premeditation and deliberation was sufficient to support first-degree murder conviction; (3) submission of mitigating factor, that defendant has no significant history of prior criminal activity, was not erroneous, even though defendant objected to submission of the mitigating factor and defendant had prior criminal record; and (4) imposition of death penalty was not excessive or disproportionate. No error. Exum, J., filed opinion dissenting as to sentence, in which Frye, J., joined.

MEYER, Justice.

Defendant brings forward numerous assignments of error relating to both the guilt-innocence phase and the sentencing phase of his trial. For the reasons stated below, we uphold his convictions for first-degree murder and for robbery with a dangerous weapon, and the sentences imposed thereon.

Defendant was charged in indictments, proper in form, with the 6 March 1983 armed robbery and murder of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon. The State's evidence at trial tended to show that at 5:47 a.m. on 6 March 1983, the Williamston Police Department received a call to the effect that the Zip Mart on Main Street seemed to be open for business, but the clerk was not there. Among those officers notified of the call was Officer Verlon Godard. Officer Godard made it known that he had just seen the clerk, Vallerie Ann Dixon, in the store while patrolling the area at 5:20 a.m. Several officers, including Godard, were immediately dispatched to the store and confirmed that Dixon and her car, a 1973 brown and tan four-door Plymouth sedan owned by her mother, were missing. The officers also found Dixon's pocketbook and a small amount of change scattered on the floor near the cash register. The store's manager was summoned, and upon her arrival, she reported that approximately $90.00 was missing from the register and safe.

At this time, the police initiated a concerted effort to find Dixon and sent Patrolman Johnny Sharp to look for her vehicle. At approximately 6:20 a.m., Patrolman Sharp reported over the radio that he had spotted the car on Highway 64. The car was heading towards town at a speed of five to ten miles per hour, and a check of the license plate number confirmed that it belonged to a member of Dixon's family. Sharp then pulled up behind the Plymouth and activated his flashing blue lights and siren. In response, the driver increased his speed and drove for several blocks in an apparent attempt to evade the patrolman. However, the car rolled to a stop just as a vehicle driven by Sergeant Donnie Hardison arrived to cut it off. The officers remained by their vehicles with guns drawn and demanded that the driver immediately exit the vehicle. After a delay of 10 to 20 seconds, a man identified as the defendant got out of the car. He was immediately placed under arrest and advised of his rights.

A search of the car incident to the defendant's arrest resulted in the discovery of a .32 caliber six-shot revolver and a paper bag containing approximately $90.00 in cash and a small change purse containing money, identification, and other items belonging to Dixon. The revolver contained four live cartridges, one spent shell, and an empty cylinder. A search of the defendant's person produced a toboggan cap with eye holes cut out of it and a pair of ski gloves. The exterior of the car was examined and found to be partly covered with fresh mud.

At the police station, the defendant was again advised of his rights and questioned by local police and Special Agent Kent Inscoe of the State Bureau of Investigation. The defendant admitted that he had walked to the Zip Mart and robbed the clerk while wearing a toboggan cap and using a .32 caliber revolver. He stated that he ordered the clerk to give him her car keys, and he proceeded to make his escape in her vehicle until being apprehended by the police. The defendant, however, denied having any knowledge of the present whereabouts of the clerk and stated that he had left her unharmed at the store. At approximately 10:00 a.m., an automobile belonging to the defendant's mother was discovered approximately 100 yards from the Zip Mart. When confronted with this information, the defendant admitted that he did not walk from his mother's house, but that he drove the car to that point.

At approximately 4:00 p.m. that same day, searchers discovered Ms. Dixon's body in an area consistent with the location defendant was headed away from when spotted that morning. The body was discovered more than one-tenth of a mile up an unpaved and muddy single-lane logging path located within five miles of town. The fully clothed body was lying face down across some washed-out tire tracks. A purple cord was tied around one wrist. Dixon's mother, with whom she lived, could not identify the cord as belonging to her daughter. Dr. Lawrence Harris, a forensic pathologist, performed an autopsy on the body of the victim. Dr. Harris testified that Dixon had been shot six times. Entrance wounds were found in the chin, the back side of the upper right arm, at the back base of the neck, the lower central part of the back, the right breast, and the back of her right thigh. Assuming that Dixon's upper body was in an upright position when struck by the bullets, the shot to the chin travelled on a slightly downward plane, while the remaining bullets travelled at an upward angle of approximately 30 degrees. Dr. Harris testified that the paths of the bullet wounds to the back were consistent with the wounds having been administered to the victim as she lay face down on the ground. He testified, however, that he could not be certain as to the position of the body when the shots were fired. Although he could not ascertain which bullet was fired first, Dr. Harris was able to conclude that Dixon slowly bled to death as a result of all six wounds over a period of approximately 15 minutes and would have lost consciousness shortly before she died. Dr. Harris also discovered a series of scratch marks approximately three and one-half inches long on Dixon's left forearm.

Special Agent Douglas Branch of the State Bureau of Investigation testified that he performed test firings with the gun which was discovered in the car at the time of defendant's arrest. He stated that, in his opinion, a comparison of the test-fired bullets with the bullets removed from Ms. Dixon revealed that she had been shot with that gun. Agent Branch had also examined the blouse the victim was wearing when she was shot. He testified that the fabric ends surrounding the bullet hole to the right front mid-section of the blouse were melted. This indicated that the muzzle of the gun was pressed into the blouse at the time that shot was fired. Agent Branch could not accurately determine the range involved with the other shots. The defendant took the stand and testified that he was living in Williamston with his mother on 6 March 1983. He testified that he awoke at approximately 6:00 a.m. and left the house in his mother's car in order to pick up his girlfriend and take her to work. Upon realizing that he was too early to take his girlfriend to work, the defendant stated that he parked his mother's car and began to jog. As he did so, he saw another man run past him and away from another automobile parked on Carolina Avenue. The defendant stated that the door to that car was open and that a gun and a bag full of money were visible on the front seat. He stated that he sat down in the car but before he could leave, the police arrived and arrested him. Defendant denied that he either robbed or killed Ms. Dixon and also denied making any admissions to the police. He acknowledged that he had been to the Zip Mart on prior occasions and that he knew Dixon as the sister of a former classmate.

On cross-examination, the defendant admitted that he had been convicted of breaking or entering in North Carolina and that he had been convicted of five armed robberies and an assault on a police officer in Virginia. However, he denied having actually committed any of those crimes. Following the presentation of all the evidence, the jury found the defendant guilty of first-degree murder and of armed robbery.

At the sentencing phase of the trial, the State introduced evidence of defendant's record of prior convictions. In 1963, defendant was convicted in Martin County of six counts of felonious larceny and six counts of breaking or entering. In 1965, defendant received an 80-year sentence in Virginia on five counts of armed robbery and one count of felonious assault. The victim of this assault, former Portsmouth, Virginia, police officer James M. Caposella, was permitted to testify regarding the details of defendant's former crimes. Mr. Caposella stated that on 5 March 1965, the defendant, in an attempt to avoid arrest, shot him three times, causing him to fall to the floor paralyzed. As the defendant ran away, he shot at the officer twice more but missed. Mr. Caposella stated that he had yet to fully recover from his injuries. The defense presented evidence of the defendant's close relationship with his mother and of his poor scholastic record in school.

At the close of the sentencing phase of the trial, the trial court submitted three possible aggravating and seven possible mitigating circumstances for the jury's consideration. The jury found each of the aggravating factors and none of the mitigating circumstances and returned a recommendation that the defendant be sentenced to death. Following the recommendation, the trial court entered judgment sentencing the defendant to death.

* * *

A careful analysis of the facts and circumstances known to the officers when they arrested the defendant clearly shows the existence of probable cause for his arrest. The evidence reveals that at 5:47 a.m., Officer Sharp was at the police station preparing to go on duty when a caller reported the absence of the clerk attending the Zip Mart on Main Street. Sharp went to the store with other officers but was unable to locate Dixon or the brown four-door Plymouth which was known to be driven by her. Both Dixon and the vehicle were seen at the Zip Mart at approximately 5:20 a.m. by Officer Verlon Godard. The officers contacted the manager of the store who, upon arrival, opened the cash register and found it empty. Officer Sharp was then dispatched to tour the vicinity and search for the Plymouth automobile. While patrolling, he spotted Dixon's vehicle travelling at a speed of five to ten miles per hour in a 45- mile-per-hour zone. Officer Sharp confirmed his identification by checking the license plate number. He then pulled behind the vehicle and activated his blue light and siren. The driver responded by rapidly accelerating to a speed of 40 to 45 miles per hour in an apparent attempt to evade Sharp. Defendant made two turns and stopped only after being cut off by a second patrol car driven by Sergeant Hardison. Sergeant Hardison and Officer Sharp, with weapons drawn, demanded that the driver get out of the Plymouth. The driver continued to sit in the car, and the officers repeated the order. Eventually, the defendant exited the vehicle. The defendant was then handcuffed, and a search of his person produced a pair of ski gloves and a toboggan cap. A search of the vehicle's passenger compartment produced a pistol and a brown paper bag containing, among other items, Dixon's driver's license and over $90.00 in cash and change.

In light of these facts and circumstances, the officers were clearly justified in making more than an investigative detention. Officer Sharp had personal knowledge of the disappearance of Dixon, her car, and the store's money. He observed Dixon's car being driven in a suspicious manner in an area near the Zip Mart soon after the disappearance was reported and at an hour when the streets were largely deserted. When the defendant discovered that he was being followed by the police, he attempted to evade apprehension. We hold that these facts and circumstances were sufficient to establish probable cause to believe that the defendant had committed a crime, including but not limited to larceny of a motor vehicle. The evidence obtained as a result of the arrest was therefore admissible against the defendant.

* * *

We conclude in the present case that there was substantial evidence that the killing was premeditated and deliberate and that it was not error to submit to the jury the question of the defendant's guilt of first-degree murder based on the theory of premeditation and deliberation. There was evidence tending to show that the Zip Mart where Dixon worked had been robbed. When arrested, the defendant was in possession of Dixon's car, personal effects belonging to Dixon, a sum of money consistent with the amount estimated to have been taken from the store, and the murder weapon. The victim's body was discovered on an isolated dirt road several miles from the store. From this evidence, the jury could reasonably infer that the defendant robbed the store, forced Dixon to accompany him in her car, and then killed her in an attempt to avoid apprehension. There was no evidence of provocation by the deceased. Further, the physical evidence tended to show that the defendant shot the deceased six times and that some of the shots may have been fired while Dixon was lying on the ground. In light of such evidence, we hold that there was sufficient evidence of premeditation and deliberation to support the defendant's conviction for first-degree murder.

* * *

The defendant next argues that the trial court erred by allowing the State during its case in chief at the sentencing hearing to present evidence of his 1963 convictions on six counts of felonious breaking or entering and six counts of felonious larceny. He contends that the evidence was introduced in order to establish the aggravating factor set out in N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(e)(3), that he had been previously convicted of a felony involving the use or threat of violence to the person. He argues that the convictions were inadmissible for this purpose because neither felonious breaking or entering nor felonious larceny have as an element the involvement of the use or threat of violence to the person, and no evidence was presented that he actually engaged in or threatened violence in order to perpetrate the offenses. See State v. McDougall, 308 N.C. 1, 301 S.E.2d 308, cert. denied, 464 U.S. 865, 104 S.Ct. 197, 78 L.Ed.2d 173 (1983). The defendant is correct in his assertion that the convictions were inadmissible to establish this aggravating factor. However, after a close examination of the record, we conclude that the convictions were not admitted for that purpose. Instead, it is apparent that the convictions were admitted to rebut the mitigating factor that the defendant had no significant history of prior criminal activity.

We derive this conclusion from an examination of the instructions given the jury at the close of the penalty phase of the trial. In discussing the aggravating factor that the defendant had been previously convicted of a felony involving the use or threat of violence, the trial judge instructed the jury that it could find this aggravating circumstance if it found the defendant had been previously convicted of robbery or the malicious shooting of Officer Caposella. No reference was made to the breaking or entering or the larceny convictions. However, when instructing the jury on the mitigating circumstance that the defendant had no significant history of prior criminal activity, the trial judge stated: "Now you would find the mitigating circumstance if you found that Willie Brown, Jr. had no prior criminal convictions, or that he had been convicted of breaking or entering, or larceny, or assault or robbery, and that this was not a significant history of prior criminal activity." (Emphasis added.) It is obvious that evidence of the breaking or entering and the larceny convictions were admitted to rebut the mitigating factor that the defendant had no significant history of prior criminal activity and was not introduced in support of any aggravating factor.

However, as noted above, the State presented the evidence of these convictions during its case in chief at the sentencing hearing. In State v. Taylor, 304 N.C. 249, 283 S.E.2d 761 (1981), cert. denied, 463 U.S. 1213, 103 S.Ct. 3552, 77 L.Ed.2d 1398, reh'g denied, 463 U.S. 1249, 104 S.Ct. 37, 77 L.Ed.2d 1456 (1983), we said that the prosecution is entitled to offer evidence designed to rebut mitigating circumstances only after the defendant offers evidence in support of such mitigating factors. We went on to hold in Taylor that the premature admission of evidence offered by the State solely to refute mitigating circumstances upon which a defendant might later rely was error (although in that case the error was found not to be prejudicial). Here, the defendant did not present evidence in support of the mitigating factor that he had no significant history of prior criminal activity. Rather, the trial judge sua sponte instructed the jury on this mitigating circumstance. The defendant therefore presented no evidence on this issue for the State to rebut. Nevertheless, since the evidence was still technically rebuttal evidence, we feel the State should have waited until the defendant had presented his evidence at the sentencing hearing before introducing these convictions into evidence. Having concluded that the trial court committed error by allowing the State to introduce this evidence "out of turn," our next task is to discern whether the error was prejudicial. We conclude that it was not.

* * *

In determining whether the evidence is sufficient to support a finding of essential facts which would support a determination that a murder was "especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel," the evidence must be considered in the light most favorable to the State, and the State is entitled to every reasonable inference to be drawn therefrom. State v. Moose, 310 N.C. 482, 313 S.E.2d 507 (1984); State v. Stanley, 310 N.C. 332, 312 S.E.2d 393 (1984).

With the above principles in mind, we find that the evidence in this case was sufficient to support the submission of this aggravating factor to the jury. The evidence presented tends to show that on the morning of 6 March 1983, the defendant robbed the Zip Mart convenience store in Williamston, North Carolina. He proceeded to force the clerk, Vallerie Dixon, to accompany him in her car. She was taken to a secluded area approximately five miles from the store and shot six times. There was also evidence to indicate that her hands had been bound. Dr. Lawrence Harris, who conducted an autopsy on the body, testified that, in his opinion, the principal cause of death was a gunshot wound to the right central lower back. He stated that the victim may have lived as long as 15 minutes after being shot. He went on to say that the victim would have gone into shock during the last phases of life and would have lost consciousness in the later stages of shock.

The defendant argues that there is no evidence as to what transpired after he left the Zip Mart with the decedent and that this precludes the finding of this aggravating factor. He cites State v. Jackson, 309 N.C. 26, 305 S.E.2d 703 (1983), in support of this assertion. In Jackson, the evidence showed that the defendant went for a ride with the decedent. Later, the defendant appeared and told friends that he had killed the decedent when he refused to give him any money. The decedent's body was later discovered in his car. He had been shot twice in the head at close range with a .22 caliber weapon. We vacated the defendant's death sentence on the ground that it was disproportionate based in part on a lack of evidence of what occurred after the defendant left with the decedent. We noted that while the crime was heinous, there was no evidence to indicate that it was "especially heinous." Id. at 46, 305 S.E.2d at 717.

In Jackson, there was simply no evidence to indicate that the victim suffered great physical pain or psychological terror prior to his murder. The same is not true in the present case. As noted earlier, the evidence would tend to show that Dixon was forced at gunpoint to leave the store with the defendant. He proceeded to drive several miles to an isolated dirt road. Clearly, Dixon was aware that she was in great danger at the time the defendant forced her to leave the store. Her anxiety undoubtedly increased as the defendant drove away from town and arrived at the secluded dirt road. We feel the evidence supports a finding that the victim was subjected to a prolonged period of terror and anguish from the time they left the store until they stopped and she was shot six times. Furthermore, Dr. Harris testified that Dixon may have lived for as long as 15 minutes after being shot and would not have lost consciousness until the final stages of life. From this testimony, it could be found that Dixon lay mortally wounded for several minutes, "aware but helpless to prevent impending death." State v. Oliver, 309 N.C. 326, 346, 307 S.E.2d 304, 318 (1983).

Dr. Harris's testimony that although shot six times, Dixon may have lived for as long as 15 minutes and would not have lost consciousness until the final stages of life, would also support a finding that she suffered great physical pain prior to death. We hold that the evidence justified the submission of the aggravating factor that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. This assignment of error is overruled.

* * *

After a careful review of the record, transcripts, other pertinent material, and other similar cases, we conclude that the defendant's sentence of death is not excessive or disproportionate. The facts tend to show that the defendant deliberately sought out and robbed a convenience store during the early morning hours when the lone employee was most vulnerable. He proceeded to rob the store, kidnap the clerk, drive her to an isolated location, and shoot her six times. The obvious motive for the killing was to prevent the clerk from identifying the defendant as the perpetrator of the robbery. The evidence would indicate that the victim did not die immediately, but may have remained conscious for up to a quarter of an hour before death. This was a senseless and brutal murder--the robbery had been completed--its sole purpose was witness elimination. We cannot say that it does not fall within the class of first-degree murders in which we have previously upheld the death penalty.... We are satisfied that the facts of this case fully support the jury's decision to recommend a sentence of death. NO ERROR.

Brown v. Lee, 319 F.3d 162 (4th Cir. N.C. 2003) (Habeas).

Following affirmance of his convictions of murder and armed robbery and death sentence on direct appeal, 315 N.C. 40, 337 S.E.2d 808, and denial of postconviction relief, petitioner sought writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, Malcolm J. Howard, J., denied writ, but granted certificate of appealability on issue of jury unanimity on mitigating circumstances. Petitioner appealed, and sought certificate of appealability on additional claims. The Court of Appeals, Traxler, Circuit Judge, held that: (1) state bar that had not been consistently applied to jury unanimity claims was not adequate and independent state ground upon which to procedurally bar federal consideration of claim, and (2) petitioner failed to make substantial showing necessary for issuance of certificate of appealability on ineffective assistance claims. Dismissed in part, reversed in part, and remanded.

TRAXLER, Circuit Judge.

Petitioner Willie Brown, Jr., filed a petition for habeas relief in the district court under 28 U.S.C.A. § 2254 (West 1994 & Supp.2002), challenging a sentence of death imposed after his conviction in North Carolina for the armed robbery and murder of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon. Brown asserts that his death sentence is constitutionally infirm because the state trial court instructed the jury that unanimity was required to find mitigating circumstances, a practice struck down by the United States Supreme Court in McKoy v. North Carolina, 494 U.S. 433, 110 S.Ct. 1227, 108 L.Ed.2d 369 (1990). Brown also contends that his trial counsel was constitutionally ineffective for failing to investigate and present additional mitigating evidence during the sentencing phase of his trial.

The district court dismissed Brown's habeas petition, but granted Brown's application for a certificate of appealability on the unanimity issue. See28 U.S.C.A. § 2253 (West Supp.2002). Brown now seeks a certificate of appealability from this court granting him permission to appeal the district court's dismissal of his ineffective assistance of counsel claim as well. For the following reasons, we reverse the district court's holding that Brown's unanimity claim is procedurally barred and remand to the district court for consideration of the merits of that claim. We deny, however, Brown's application for a certificate of appealability on the ineffective assistance of counsel claim.

In November 1983, a North Carolina jury convicted Brown of the armed robbery and murder of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon. The facts leading to Brown's conviction are fully set forth by the North Carolina Supreme Court in State v. Brown, 315 N.C. 40, 337 S.E.2d 808 (1985). Given the more narrow issues before us, a brief summary will suffice here.

At approximately 5:47 a.m. on the morning of March 6, 1983, a Zip Mart convenience store on Main Street in Williamston, North Carolina, where Ms. Dixon was supposed to be working as a clerk, was reported empty. A patrolling police officer had seen Ms. Dixon in the store less than thirty minutes prior to the report. Money from the cash register and a store safe was missing, as was Ms. Dixon's automobile. A search for Ms. Dixon was immediately begun.

At about 6:20 a.m., a police officer spotted Ms. Dixon's automobile traveling on a nearby road. The automobile was stopped by police officers, and Brown, who was driving alone in the vehicle, was immediately placed under arrest and advised of his rights. A .32 caliber six-shot revolver, a paper bag containing approximately $90 in cash and change, and a change purse containing Ms. Dixon's drivers license and social security card were found in the automobile. A pair of ski gloves and a toboggan cap with eye holes cut out of it were found on Brown's person. The exterior of the car was partly covered with fresh mud. According to the police officers, Brown admitted that he robbed the Zip Mart and fled in Ms. Dixon's car, but claimed that Ms. Dixon was unharmed when he left the store. At approximately 4:00 p.m. that afternoon, Ms. Dixon's body was found on a muddy logging road in a rural area outside Williamston. Forensic pathology and firearm tests revealed that Ms. Dixon had been shot six times with the .32 caliber revolver that police had found in Dixon's car at the time of Brown's arrest. Brown testified at his trial and disputed the police officers' version of the events that day. Brown testified that, while he was jogging near the Zip Mart, a man ran past him and away from a parked car with an opened door. Brown testified that he saw a gun and bag of money on the seat of the car, sat down in the vehicle, and was arrested by police before he could get out of the vehicle. Brown denied robbing or killing Ms. Dixon, and denied making any admissions to the police. On cross-examination, Brown admitted that he had been previously convicted in North Carolina of breaking and entering and in Virginia for five armed robberies and the assault of a police officer. He denied, however, that he was guilty of committing those crimes.

Following the presentation of all the evidence, the jury convicted Brown of first-degree murder and robbery with a dangerous weapon. A capital sentencing proceeding was then held, seeN.C. Gen.Stat. § 15A-2000 (2001), during which additional details of Brown's prior convictions in North Carolina and Virginia were presented to the jury. Brown had been convicted in 1963 in North Carolina of six counts of felonious larceny and six counts of breaking or entering. In 1965, Brown was convicted in Virginia of five counts of armed robbery and one count of felonious assault. The victim of the assault was a Virginia police officer, who testified at the sentencing hearing that he was shot and paralyzed when Brown shot him three times in an attempt to avoid arrest.

In mitigation, Brown presented the testimony of law enforcement officers who testified that he offered no resistance to his arrest for murder, that he was not disrespectful during interrogation, and that he had an intense emotional reaction, crying and shaking, when questioned about Ms. Dixon. Brown also presented testimony from his mother, who testified that Brown was the second of seven children, that he was born and raised in Williamston, that he was not a good student, that his father died in 1973, that she had visited him regularly in prison, and that he had treated her with respect when he returned to live at home after his release from prison. Brown's school records documenting his poor scholastic record were also presented.

At the conclusion of the sentencing phase of the trial, three potential aggravating circumstances were submitted for consideration by the jury: (1) that Brown had previously been convicted of a felony involving the use of threat or violence to the person; (2) that the murder was committed by Brown while he was engaged in the commission of or flight after committing a robbery; and (3) that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel. The jury found all three aggravating circumstances to be present.

The trial court submitted seven possible mitigating circumstances for the jury's consideration: (1) that Brown had no significant history of prior criminal activity; (2) that Brown was a person of limited intelligence and education; (3) that Brown was under the age of 21 at the time he committed any previous felonies for which he had been convicted; (4) that Brown had not been convicted of any criminal offense for 18 years; (5) that Brown surrendered at the time of his arrest without resistance to law enforcement officers; (6) that Brown confessed soon after his arrest to robbing the Zip Mart; and (7) any other circumstances which the jury deemed to have mitigating value.

The jury found no mitigating circumstances and returned a recommendation that Brown be sentenced to death for the murder conviction. Following the recommendation, the trial court imposed the sentence. The North Carolina Supreme Court affirmed Brown's conviction and death sentence, see Brown, 337 S.E.2d at 830, and the United States Supreme Court denied Brown's petition for writ of certiorari. See Brown v. North Carolina, 476 U.S. 1164, 106 S.Ct. 2293, 90 L.Ed.2d 733 (1986).

* * *

For the foregoing reasons, we hold that North Carolina has not regularly and consistently applied its procedural default rule in section 15A-1419(a) to claims challenging unanimity instructions and, therefore, that the district court erred in holding that the state bar is an adequate and independent ground procedurally barring federal court consideration of Brown's unanimity claim on federal habeas review. Accordingly, we remand this case for consideration by the district court of the merits of the unanimity claim.

Because Brown has failed to make a substantial showing that his constitutional rights were violated by his counsel's failure to present additional mitigating evidence at his capital sentencing hearing, we deny a certificate of appealability on that issue. DISMISSED IN PART, REVERSED IN PART, AND REMANDED.

Brown v. Polk, 135 Fed.Appx. 618 (4th Cir. N.C. 2005) (Unpublished) (Habeas).

Background: Defendant was convicted in the Superior Court, Martin County, Donald L. Smith, J., of first-degree murder and robbery with a dangerous weapon, and death sentence was imposed for murder conviction. Defendant appealed as a matter of right. The Supreme Court, Meyer, J., 337 S.E.2d 808, found no error, and defendant petitioned for federal habeas relief. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, Malcolm J. Howard, J., denied petition, and defendant appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Traxler, Circuit Judge, held that:

(1) United States Supreme Court's decision in Mills, as to unconstitutionality of jury instructions in capital case that might be interpreted to prevent consideration of mitigating circumstances unless jury was unanimous in finding existence of such circumstances, was not watershed rule of criminal procedure implicating fundamental fairness and, as new rule of criminal procedure, could not be applied retroactively to habeas petitioner whose capital murder conviction had already become final; and

(2) state postconviction relief court's decision that movant's counsel did not behave deficiently in failing to anticipate new rule of law, and in failing to challenge unanimity instruction given to jury in capital murder case, was neither contrary to nor an unreasonable application of governing Supreme Court law, as required for federal court to disturb state court's decision on habeas review.

Affirmed.

TRAXLER, Circuit Judge.

Petitioner Willie Brown, Jr., appeals the district court's denial of his petition for a writ of habeas corpus under 28 U.S.C.A. § 2254 (West 1994 & Supp.2005), which alleged (1) that his death sentence violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution because the jury was instructed that it must unanimously find the existence of any mitigating *620 circumstances; and (2) that his appellate counsel rendered constitutionally ineffective assistance by failing to argue this unanimity issue on direct appeal to the North Carolina Supreme Court. For the following reasons, we affirm.

I.

In November 1983, a North Carolina jury convicted Brown of the armed robbery and first-degree murder of Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon. The facts leading to Brown's conviction are fully set forth by the North Carolina Supreme Court in State v. Brown, 315 N.C. 40, 337 S.E.2d 808 (1985), and by this court in Brown v. Lee, 319 F.3d 162 (4th Cir.2003). For purposes of this appeal, the following excerpt will suffice:

At approximately 5:47 a.m. on the morning of March 6, 1983, a Zip Mart convenience store on Main Street in Williamston, North Carolina, where Ms. Dixon was supposed to be working as a clerk, was reported empty. A patrolling police officer had seen Ms. Dixon in the store less than thirty minutes prior to the report. Money from the cash register and a store safe was missing, as was Ms. Dixon's automobile. A search for Ms. Dixon was immediately begun.

At about 6:20 a.m., a police officer spotted Ms. Dixon's automobile traveling on a nearby road. The automobile was stopped by police officers, and Brown, who was driving alone in the vehicle, was immediately placed under arrest and advised of his rights. A .32 caliber six-shot revolver, a paper bag containing approximately $90 in cash and change, and a change purse containing Ms. Dixon's drivers license and social security card were found in the automobile. A pair of ski gloves and a toboggan cap with eye holes cut out of it were found on Brown's person. The exterior of the car was partly covered with fresh mud. According to the police officers, Brown admitted that he robbed the Zip Mart and fled in Ms. Dixon's car, but claimed that Ms. Dixon was unharmed when he left the store.

At approximately 4:00 p.m. that afternoon, Ms. Dixon's body was found on a muddy logging road in a rural area outside Williamston. Forensic pathology and firearm tests revealed that Ms. Dixon had been shot six times with the .32 caliber revolver that police had found in Dixon's car at the time of Brown's arrest. Id. at 165. In November, 1983, Brown was tried and convicted of first degree murder and the capital sentencing phase of the trial began. At the conclusion of the sentencing phase, the jury found three aggravating circumstances.FN1 The trial court submitted seven possible mitigating circumstances for the jury's consideration, but the jury found none.FN2 The jury returned a recommendation that Brown be sentenced to death for the murder conviction. On appeal to the North Carolina Supreme Court, counsel raised seventeen claims of error, but did not assert that the trial judge erred in instructing the jury that mitigating circumstances must be found unanimously. The North Carolina Supreme Court affirmed Brown's conviction and death sentence, see Brown, 337 S.E.2d at 830, and the United States Supreme Court denied Brown's petition for writ of certiorari in 1986. See Brown v. North Carolina, 476 U.S. 1164, 106 S.Ct. 2293, 90 L.Ed.2d 733 (1986).

FN1. The jury found the following aggravating circumstances: (1) that Brown had previously been convicted of a felony involving the use of threat or violence to the person; (2) that the murder was committed by Brown while he was engaged in the commission of or flight after committing a robbery; and (3) that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel.

FN2. The mitigating circumstances submitted to the jury for consideration were (1) that Brown had no significant history of prior criminal activity, (2) that Brown was a person of limited intelligence and education, (3) that Brown was under the age of 21 at the time he committed any previous felonies for which he had been convicted, (4) that Brown had not been convicted of any criminal offense for 18 years, (5) that Brown surrendered at the time of his arrest without resistance to law enforcement officers, (6) that Brown confessed soon after his arrest to robbing the Zip Mart, and (7) any other circumstances which the jury deemed to have mitigating value.

On March 9, 1987, Brown filed a motion for appropriate relief (“MAR”), seeking state habeas relief. For the first time, Brown asserted that the trial court had erroneously instructed the jury that it must unanimously find any mitigating circumstances, in violation of his rights under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. On November 19, 1987, the MAR court concluded that, because Brown had been in a position to raise the unanimity issue before the North Carolina Supreme Court on direct appeal but had failed to do so, he was procedurally barred from raising it on state habeas.

Six months prior to Brown's November 1983 conviction, the North Carolina Supreme Court rejected a claim that it was error for the trial court to instruct the jury that it must unanimously find mitigating circumstances. See State v. Kirkley, 308 N.C. 196, 302 S.E.2d 144, 156-57 (1983). However, on June 6, 1988 (five years after Kirkley was decided and two years after Brown's conviction became final), the United States Supreme Court reversed a death sentence imposed in Maryland because there was “a substantial probability that reasonable jurors ··· well may have thought they were precluded from considering any mitigating evidence unless all 12 jurors agreed on the existence of a particular such circumstance.” Mills v. Maryland, 486 U.S. 367, 384, 108 S.Ct. 1860, 100 L.Ed.2d 384 (1988). Two years later, the Supreme Court held that North Carolina's unanimity requirement likewise failed to pass constitutional muster. See McKoy v. North Carolina, 494 U.S. 433, 443, 110 S.Ct. 1227, 108 L.Ed.2d 369 (1990) (holding that the Constitution requires that “each juror must be allowed to consider all mitigating evidence in deciding ··· whether aggravating circumstances outweigh mitigating circumstances, and whether the aggravating circumstances, when considered with any mitigating circumstances, are sufficiently substantial to justify a sentence of death”).

In the wake of these Supreme Court decisions, Brown made a number of attempts to re-raise the unanimity issue on state habeas and to obtain reconsideration of the state MAR court's November 1987 order finding the claim to be procedurally barred, but was unsuccessful. See Brown, 319 F.3d at 166-67. On June 16, 1997, the state court denied all remaining claims for state MAR relief, including Brown's claim that his counsel was ineffective for failing to raise the unanimity issue on direct appeal, and the North Carolina Supreme Court denied Brown's petitions for writ of certiorari and for reconsideration. See State v. Brown, 505 S.E.2d 879 (N.C.1998); State v. Brown, 501 S.E.2d 920 (1998). The United States Supreme Court denied Brown's petition for writ of certiorari. See Brown v. North Carolina, 525 U.S. 888, 119 S.Ct. 204, 142 L.Ed.2d 167 (1998).

On December 24, 1998, Brown filed his petition for habeas relief in the district court under 28 U.S.C.A. § 2254, raising eleven constitutional challenges to his conviction and sentence, including claims that his jury was improperly instructed that it had to be unanimous in finding any mitigating circumstances, and that his counsel was constitutionally ineffective in failing to raise the unanimity claim on direct appeal to the North Carolina Supreme Court.

On February 25, 2002, the district court granted the State's motion for summary judgment, denied Brown's motion for summary judgment, and dismissed Brown's habeas petition. With regard to the unanimity claim, the district court concluded that it was precluded from reviewing the merits of the claim because the state court procedurally barred Brown from raising it on state habeas under an adequate and independent state law ground. The district court also rejected Brown's claim that his appellate counsel was constitutionally ineffective for failing to raise the unanimity claim on direct appeal. Brown's subsequent motion to alter or amend the judgment was also denied.

In May 2002, Brown filed an application for a certificate of appealability, seeking, inter alia, to appeal the district court's conclusion that it was procedurally barred from considering the unanimity claim, including the finding that counsel's failure to raise the issue on direct appeal did not constitute cause to excuse the procedural default. The district court granted Brown's application for a certificate of appealability as to the unanimity claim. See28 U.S.C.A. § 2253 (West Supp.2005).

On February 14, 2003, we reversed the district court's holding that it was precluded from considering the merits of Brown's unanimity claim under the doctrine of procedural default because North Carolina “[had] not regularly and consistently applied its procedural default rule ··· to claims challenging unanimity instructions.” Brown, 319 F.3d at 177. Because our precedent at the time was that the unanimity holdings in Mills and McKoy were exceptions to the general rule that “new rules” of constitutional procedure do not apply retroactively to cases on collateral review, see Williams v. Dixon, 961 F.2d 448, 453 (4th Cir.1992), we remanded the unanimity claim to the district court for consideration on the merits, see Brown, 319 F.3d at 168, 177. And, because remand for a determination on the merits was in order, we found it unnecessary to address Brown's claim that his appellate counsel was ineffective for failing to raise the unanimity issue on direct appeal to the state court. See id. at 175 n. 4.

After our decision was issued remanding the case for a decision on the merits, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in the case of Beard v. Banks to address the question of whether Mills v. Maryland announced a “new rule” under Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288, 109 S.Ct. 1060, 103 L.Ed.2d 334 (1989), not applicable retroactively to cases on federal habeas review. See Beard v. Banks, 539 U.S. 987, 124 S.Ct. 45, 156 L.Ed.2d 704 (2003). Because this directly impacted our decision in Williams and the propriety of the district court's examination of the merits of the unanimity claim on remand, the district court issued an order on January 7, 2004, holding Brown's case in abeyance pending a decision by the United States Supreme Court in Beard.

On June 24, 2004, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Beard, holding that McKoy announced a new rule of law that did not fall within either of the Teague exceptions to the general rule of nonretroactivity, effectively overruling our decision in Williams. See Beard v. Banks, 542 U.S. 406, ----, 124 S.Ct. 2504, 2515, 159 L.Ed.2d 494 (2004). Accordingly, under the Supreme Court's directive in Beard, federal habeas courts are precluded from applying the unanimity rules of Mills and McKoy retroactively to state death penalty cases that became final before the rule was announced. See id.

On August 25, 2004, the district court issued an order granting the state's motion for summary judgment with respect to *623 Brown's unanimity claim. Because the United States Supreme Court had denied Brown's petition for a writ of certiorari on June 2, 1986, well before the Supreme Court issued its decisions in Mills or McKoy, the district court concluded that Brown was not entitled to a writ of habeas corpus. The district court denied Brown's subsequent motion to alter or amend the judgment.FN3

FN3. Because the merits of the unanimity claim were never addressed by this court, and there is no dispute that the controlling legal authority regarding Teague' s application changed dramatically after our remand, the “mandate rule” did not prevent the district court from denying the claim on the basis of Teague. See United States v. Bell, 5 F.3d 64, 66-67 (4th Cir.1993).

In November 2004, Brown filed an application for a certificate of appealability with the district court, seeking to appeal the district court's finding that Teague and Beard prohibit application of the rule in Mills and McKoy to Brown's case, as well as the district court's prior ruling that Brown's appellate counsel was not ineffective for failing to raise the McKoy error in Brown's direct appeal to the state court. The district court granted Brown's application for a certificate of appealability as to the unanimity claim, and we granted Brown's application for a certificate of appealability as to the ineffective assistance of counsel claim.

* * *

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the district court is affirmed.

Brown v. Beck, 2006 WL 1030236 (4th Cir. N.C. 2006) (Injunction).

PER CURIAM.

By order dated April 17, 2006, the district court denied the motion of Willie Brown, Jr. for a preliminary injunction enjoining the defendants from carrying out his execution which is scheduled for Friday, April 21, 2006. Brown has filed a notice of appeal to this Court from that order, a motion for preliminary injunction and a brief in support. Appellees filed a brief opposing appellant's motion for preliminary injunction.

The Court affirms the district court's denial of a preliminary injunction and directs the clerk to issue the mandate forthwith.

Entered at the direction of Judge Luttig with the concurrence of Judge Traxler. Judge Michael wrote the attached dissent.

MICHAEL, Circuit Judge, dissenting.

I respectfully dissent from the majority's affirmance of the district court's denial of a preliminary injunction to temporarily block the execution of Willie Brown, Jr. Brown is a North Carolina death row inmate scheduled to be executed by lethal injection on April 21, 2006, at 2:00 a.m. He filed a § 1983 action seeking to enjoin the warden and others (“the State”) from executing him by lethal injection under the procedures the State intended to employ. Specifically, Brown contends that the State will use an inadequate protocol for anesthesia as a precursor to carrying out his death sentence, and that as a result he faces an unacceptable and unnecessary risk of suffering excruciating pain during his execution in violation of the Eighth Amendment. See Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 173 (1976) (recognizing, in the context of executions, that the Eighth Amendment prohibits punishment “involv[ing] the unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain”); In re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436, 447 (1890) (recognizing that the Eighth Amendment prohibits “torture or a lingering death”). The district court, in its final order, denied Brown's motion for a preliminary injunction enjoining his execution on the ground that the State's revised protocol ensures that Brown will be rendered unconscious during the execution and will not feel pain. Because this finding is not supported by the clear weight of the evidence, I would reverse.

In its April 7, 2006, order the district court determined that there were “substantial questions as to whether North Carolina's execution protocol creates an undue risk of excessive pain.” (Order, 13-14, Apr. 7, 2006.) Specifically, the court found that inadequate administration of anesthesia prior to execution would undisputedly make Brown “suffer excruciating pain as a result of the administration of pancuronium bromide and potassium chloride.”( Id. at 12.) The court further determined that any difficulties could be addressed if there are present and accessible to [Brown] throughout the execution personnel with sufficient medical training to ensure that [Brown] is in all respects unconscious prior to and at the time of the administration of any pancuronium bromide or potassium chloride. Should [Brown] exhibit effects of consciousness at any time during the execution, such personnel shall immediately provide appropriate medical care so as to insure [Brown] is immediately returned to an unconscious state.

On April 12, 2006, the State responded by proposing a revised protocol that uses a bispectral index (BIS) monitor, a device that, according to the State, can monitor Brown's level of consciousness during the execution procedure. Over Brown's objections, the district court determined that the revised protocol will ensure that Brown is rendered unconscious prior to and throughout the period during which lethal drugs are injected into his bloodstream, so that he will not perceive pain during his execution. The court stated,