12th murderer executed in U.S. in 2009

1148th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Alabama in 2009

40th murderer executed in Alabama since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

Danny Joe Bradley W / M / 23 - 49 |

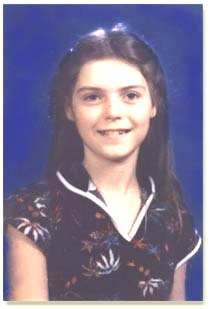

Rhonda Hardin W / F / 12 |

Summary:

12 -year-old Rhonda Hardin and her younger brother, Bubba, were left in the care of their stepfather, Danny Joe Bradley. The mother of the children, Judy Bradley, had been hospitalized for more than one week. At approximately 8:00 p.m., Rhonda was watching television with Bubba and Bradley. Rhonda was lying on the couch and asked Bubba to wake her if she fell asleep so that she could move to the bedroom. When Bubba decided to go to bed, Bradley told him not to wake Rhonda but to leave her on the couch. Bradley also told Bubba to go to sleep in the room normally occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Bradley instead of his own bedroom. Bradley claimed that he had fallen asleep and that when he awoke, Rhonda was gone. Her body was found the next day in woods near Bradley's apartment. She had been raped, sodomized and strangled to death. When he discovered her "missing" Bradley went to his in-laws, then to the next door neighbor, before going to the hospital. He claimed to police that he had not left the house before discovering her missing, but was witnessed by a police officer near where the body was eventually discovered. Her brother later testified that Bradley had frequently rendered the children unconscious by squeezing their necks. Fiber evidence from Bradley's home and trunk was also consistent with clothing and bedding fibers from the victim.

Citations:

Bradley v. State494 So.2d 750 (Ala.Cr.App. 1985) (Direct Appeal).

Bradley v. State557 So.2d 1339 (Ala. Cr. App 1989) (PCR).

Bradley v. Nagle212 F.3d 559 (11th Cir. 2000) (Habeas).

Bradley v. King, --- F.3d ----, 2009 WL 242399 (11th Cir. 2009) (Sec. 1983 - DNA).

Final/Special Meal:

Bradley had no final meal request. He had two fried egg sandwiches for breakfast and a snack during the day.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Alabama Department of Corrections

DOC#: 00Z438 Inmate: BRADLEY, DANNY JOE Gender: M Race: W DOB:9/7/1959 Prison Holman Received: 8/8/1983 Charge: MURDER County: CALHOUN

"Inmate executed for rape, murder of stepdaughter." (Published: Friday, February 13, 2009 at 3:30 a.m.)

ATMORE | Danny Joe Bradley was executed Thursday for the rape and strangulation of his 12-year-old stepdaughter, Rhonda Hardin.

Bradley, 49, was given a lethal injection at 6:15 p.m. at Holman prison after spending 25 years on Alabama’s death row. He had no final statement. His sister was one of the witnesses.

His attorney had asked the Supreme Court to stay the execution to allow more court review of Bradley’s civil rights lawsuit on a DNA- related issue from his trial in Calhoun County. The U.S. Supreme Court denied the request late Thursday afternoon.

"Execution delay sought for Alabama killer," by Garry Mitchell. (Associated Press Published: February 3, 2009)

MOBILE, Ala. (AP) — An attorney for Alabama death row inmate Danny Joe Bradley, who was convicted of the 1983 rape and murder of his 12-year-old stepdaughter, has asked a federal appeals court to block his scheduled execution next week. But prosecutors said the 48-year-old Bradley, of Piedmont in northeast Alabama, has exhausted his appeals and his execution by lethal injection, set for Feb. 12 at Holman prison near Atmore, should not be delayed. It is the second of five executions scheduled in the first five months of this year, an unusual grouping for Alabama, which had no executions last year.

Bradley attorney Theodore A. Howard of Washington, D.C., said Tuesday by e-mail that the Atlanta-based 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals was asked to stay the execution because the appeals court has not settled a DNA issue pending before it in Bradley’s case. DNA testing was not available when Bradley was tried, and the Alabama Supreme Court in 2001 granted him a stay of execution pending DNA testing of evidence.

It turned out that some critical evidence sought — rape kit swabs, slides from the autopsy and semen-stained clothing of the 12-year-old girl — had been lost, but bedding items were found. A federal judge in Birmingham in 2007 denied Bradley’s suit over the missing evidence. Bradley appealed to the 11th Circuit, which has not yet ruled.

Assistant Attorney General Clay Crenshaw, Alabama’s capital litigation chief, has urged the 11th Circuit not to delay the execution. In a recent filing with the appeals court, he said that bedding items, which were kept as evidence, were DNA-tested, establishing Bradley’s guilt without a doubt.

It was unclear Tuesday when the appeals court might rule on the stay request. The stay Bradley received in 2001 came one week before he was to die.

His conviction was in the Jan. 24, 1983, killing of his stepdaughter, Rhonda Hardin. Bradley was caring for the girl and her younger brother, Gary “Bubba” Hardin, when she was raped, sodomized and strangled after her brother went to sleep. The children’s mother was in the hospital. Rhonda’s body was found the next morning in some woods less than a mile from Bradley’s apartment. Her brother later testified in the Calhoun County trial that Bradley had frequently rendered the children unconscious by squeezing their necks.

In Alabama’s most recent execution, 62-year-old James Harvey Callahan, also of Calhoun County, was given a lethal injection last month for the 1982 kidnapping, rape and killing of a Jacksonville woman.

"Rapist-killer of stepdaughter faces execution." (Associated Press • February 12, 2009)

ATMORE, — Danny Joe Bradley looked for the U.S. Supreme Court to block his execution Thursday for the rape and strangulation of his 12-year-old stepdaughter, but state prosecutors say his appeals have run out. Awaiting a high court decision, Bradley, 49, faced lethal injection at 6 p.m. Thursday at Holman prison after 25 years on Alabama's death row.

Bradley's attorney sought a Supreme Court stay of execution to allow more court review of Bradley's civil rights lawsuit on a DNA-related issue from his trial in Calhoun County, but lower courts have already denied that request. Both the Alabama Supreme Court and the Atlanta-based 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals earlier refused to block Bradley's execution — the second of five set in Alabama in the first five months of this year. The state had no executions last year.

Bradley was caring for Rhonda Hardin and her 11-year-old brother, Gary "Bubba" Hardin, on Jan. 24, 1983, in Piedmont when the girl was slain. The children's mother had been hospitalized for more than a week. Bradley claimed that he had fallen asleep and that when he awoke, Rhonda was gone. Her body was found the next day in woods near Bradley's apartment. She had been raped and sodomized, according to court records.

Now the father of a 12-year-old son, Rhonda's brother told The Anniston Star in a recent interview that he hasn't forgiven Bradley and can't imagine losing a child at that age. At Bradley's trial, the brother said Bradley had frequently rendered the children unconscious by squeezing their necks.

Judy Bennett, of Piedmont, who divorced Bradley, recalled her daughter as a lovable child who liked to turn cartwheels and spin around. "It's really bad she was violated in such a horrible way," Bennett told the Anniston newspaper.

Theodore Howard, Bradley's attorney in Washington, D.C., told the U.S. Supreme Court in a filing Wednesday that Bradley's case had been stopped "midstream" and a stay would allow it to continue. DNA testing was not available at the original trial. Bradley first attempted to locate items for DNA testing in July 1996 with help from a law student associated with the Innocence Project and filed suit in 2001 for DNA testing when his execution was imminent, court records show.

In 2001, the Alabama Supreme Court granted Bradley a stay only a week before his scheduled execution to allow DNA testing of bedding items. Rhonda's DNA and Bradley's DNA were mixed on a blanket that was on Rhonda's bed, according to court records. However, some critical evidence has been lost, including the rape kit and semen-stained clothing. Bradley's attorney filed a civil rights suit in hopes of questioning a forensics serologist who had given an affidavit about the lost evidence.

A federal judge in Birmingham refused the request and the 11th Circuit upheld that decision, ruling that "there are no extraordinary circumstances in Bradley's case entitling him to further post-conviction access to DNA evidence." "Enough is enough," Alabama Attorney General Troy King said in a Supreme Court filing opposing further delays.

In Alabama's most recent execution, James Harvey Callahan, 62, also of Calhoun County, was given a lethal injection last month for the 1982 kidnapping, rape and killing of a Jacksonville woman. Alabama has 207 inmates on death row, including four women.

On January 24, 1983, twelve-year-old Rhonda Hardin and her younger brother, Gary "Bubba" Hardin, were left in the care of their stepfather, Danny Joe Bradley. The children's mother, Judy Bradley, had been hospitalized for more than one week. The children normally slept in one bedroom of the residence and Danny Joe Bradley and Mrs. Bradley in another.

On the night of January 24, 1983, Jimmy Isaac, Johnny Bishop, and Dianne Mobley went to the Bradley home where they saw Rhonda and Bubba together with Danny Joe Bradley. When Bishop, Mobley, and Isaac left the Bradley home at approximately 8:00 p.m., Rhonda was watching television with Bubba and Bradley. Rhonda was lying on the couch, having taken some medicine earlier in the evening. She asked Bubba to wake her if she fell asleep so that she could move to the bedroom. When Bubba decided to go to bed, Bradley told him not to wake Rhonda but to leave her on the couch. Bradley also told Bubba to go to sleep in the room normally occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Bradley instead of his own bedroom.

At approximately 11:30 p.m., Bradley arrived at the home of his brother-in-law, Robert Roland. Roland testified that Bradley arrived driving his automobile and that he was "upset" and "acted funny." Roland testified that Bradley "talked loud and acted like he was nervous and all, which I had never seen him do before." Bradley's father-in-law, Ed Bennett, testified that Bradley came to his house at approximately midnight and told him that Rhonda was gone.

Bradley's next-door neighbor, Phillip Manus, testified that at approximately 12:50 a.m., Bradley appeared at his home. Manus testified that Bradley told him that he and Rhonda had argued over some pills Rhonda wanted to take. He claimed that he had fallen asleep and when he awoke, Rhonda was missing. Bradley then said "[l]et me run over to Rhonda's grandma's house and I'll be back in a few minutes." Bradley returned ten or fifteen minutes later. Manus suggested that they walk to the hospital to tell Judy Bradley that Rhonda was missing. Manus testified that Bradley wanted to go to the hospital rather than report Rhonda's disappearance to the police. Manus and Bradley waited at the hospital for one and one-half hours before they were able to enter Mrs. Bradley's room. Throughout that period of time, Manus tried to persuade Bradley to go to the police station to report that Rhonda was missing. When the men eventually saw Mrs. Bradley, she told Danny Joe Bradley to report Rhonda's disappearance to the police. Manus and Bradley went to the police station where Bradley told Officer Ricky Doyle that Rhonda was missing. Bradley also told Officer Doyle that he and Rhonda had argued earlier in the evening and that she had left the house sometime around 11:00 or 11:30 p.m. Bradley claimed that he had fallen asleep and that when he awoke, Rhonda was gone. He stated that he left the house at 11:30 p.m. to go to his neighbor's house to look for Rhonda. Bradley specifically indicated that he had not left the house until he began looking for Rhonda and that he went to the Manus home when he learned that Rhonda was missing.

After talking with Officer Doyle, Bradley and Manus returned to Manus's apartment. At approximately 7:30 a.m. on January 25, 1983, Rhonda's body was found in a wooded area less than six-tenths of a mile from Bradley's apartment. Rhonda's body was dressed in a pair of maroon-colored corduroy pants, a short-sleeved red knit shirt, green, white, brown, and purple striped leg warmers, a bra, and a blue windbreaker. Rhonda's tennis shoes were tied in single knots. Several members of her family testified that she always tied her shoes in double knots.

Within ninety minutes after Rhonda's body was discovered, two plainclothes officers from the Piedmont Police Department arrived at Bradley's residence. The officers had neither an arrest warrant nor probable cause. Although the government contends that Bradley was not placed under arrest at that time, Bradley claims that he was told he was under arrest for suspicion of murder, handcuffed, placed in a police vehicle, and taken to the Police Station, where an interrogation began at around 9:30 a.m. Bradley was in the custody of the Piedmont Police from that time until approximately 4:00 a.m. on the following morning. During this period of almost nineteen hours, the officers read Bradley his Miranda rights and questioned him. Bradley told the police that he had discovered Rhonda missing at approximately 11:20 or 11:25 p.m. and had gone to Phillip Manus's house in search of her. He also told officers that he had not left the apartment until he began his search for Rhonda.

In addition to giving a statement, Bradley executed a consent-to-search form authorizing the police to search his residence and his automobile, submitted to fingernail scraping, and was transported to and from Birmingham, Alabama. While in Birmingham, he submitted to a polygraph test and blood and saliva tests, and gave his clothing to the authorities. Although Bradley cooperated with the police in their investigation during this time period, he claims that he did so because the police clearly indicated to him that he would remain in police custody unless he cooperated. After obtaining the consent-to-search form, the police searched his residence and his automobile, seizing several items of physical evidence. Among the seized items of evidence were a pillowcase, a damp blue towel from a bathroom closet, the living room light switch plate cover, a red, white, and blue sheet from the children's bedroom, a white "heavy" sheet from the washing machine, and fiber samples from the trunk of Bradley's automobile.

Prior to the trial, the court denied Bradley's two motions to suppress this evidence. At trial, the State presented testimony that, contrary to Bradley's statements to police on both January 24 and January 25, 1983, Police Officer Bruce Murphy had seen Bradley in his car at 9:30 p.m. in the area where Rhonda's body was discovered. Officer Murphy, who had known Bradley for more than twenty years, positively identified him.

The State's forensic evidence demonstrated that Bradley's fingernail scrapings matched the red, white, and blue sheet taken from the children's bedroom, the fibers from the leg warmers found on Rhonda's body, and the cotton from the pants Rhonda was wearing on January 24, 1983. The State also proved that fibers found in the trunk of Danny Joe Bradley's car matched the fibers from Rhonda's clothing.

A pathologist testified that Rhonda's body had "evidence of trauma-that is, bruises and abrasions on her neck." She had seven wounds on her neck; the largest was an abrasion over her Adam's apple. The pathologist testified that he had taken swab and substance smears from Rhonda's mouth, rectum, and vagina. He also removed the gastric contents from Rhonda's stomach and turned them over to the toxicologist. An expert in forensic serology testified that Danny Joe Bradley and Rhonda Hardin were of type O blood. Bradley is a non-secretor of the H-antigen. Rhonda was a secretor. The serology expert testified that the H-antigen was not present in the semen taken from the rectal swab of Rhonda. The rectum does not produce secretions or H-antigens. On the inside of Rhonda's pants, a stain containing a mixture of fecal-semen was found with spermatozoa present.

The pillowcase found in the bathroom revealed high levels of seminal plasma and spermatozoa consistent with the type O blood group. There were small blood stains on the pillowcase mixed with saliva. These stains were also consistent with an O blood group. The red, white, and blue sheet on the bed in the children's bedroom contained a four by two and one-half inch stain which included spermatozoa. The white blanket which had been placed in the washing machine also had two large stains consistent with fecal-semen. In both stains, spermatozoa was present and no H-antigens were detected. A combination of semen and sperm with the H-antigen was found on the blue towel located in the bathroom. Although the written report indicated that the blue towel contained a fecal-semen stain containing the H-antigen, the expert testified at trial that her analysis revealed that the towel contained a vaginal-semen stain not a fecal-semen stain and that the word fecal instead of vaginal had been essentially a scriveners' error. She testified that because the blue towel contained a vaginal semen stain, the H-antigen secretions could have come from Rhonda's vaginal secretions. The serologist testified that the low level of H-antigen was consistent with a female secretor because the H-antigen is present in low levels in the vagina. The mattress cover contained a number of seminal stains.

At trial, Bradley's sister-in-law also testified that a day after Rhonda's funeral she heard Bradley say "I know deep down in my heart that I done it," and Bradley's stepson, Bubba Hardin, testified that Bradley had frequently rendered the children unconscious by squeezing their necks.

Bradley testified in his own defense. He explained his inconsistent statements to police by suggesting that he had left his home at the time he was observed by Officer Murphy, because he had intended to steal a car, remove its motor, and sell it. He claimed that Gary Hardin, the father of Bubba and Rhonda, had asked him to obtain such a motor. Hardin testified that he had made no such request. The jury returned a verdict of guilty of capital murder on counts one and three of the indictment. These counts charged murder during the commission of a rape or sodomy in the first degree. The same jury deliberated in the punishment phase and recommended twelve to zero that Bradley be sentenced to death.

"Alabama executes Danny Joe Bradley for 1983 assault and slaying of stepdaughter in Piedmont," by Tom Gordon. (February 12, 2009 6:20 PM)

Danny Joe Bradley, a resident of Alabama's Death Row for more than 26 years, was executed by lethal injection and pronounced dead at 6:15 p.m. today at Holman Correctional Facility. The U.S. Supreme Court earlier in the day denied a stay of execution clearing the way for him to be put to death for the rape and strangulation of his 12-year-old stepdaughter.

Bradley's attorney had sought a Supreme Court stay of execution to allow more court review of Bradley's civil rights lawsuit on a DNA-related issue from his trial in Calhoun County, but lower courts had already denied that request.

Bradley, 49, was convicted of murdering his 12-year-old stepdaughter, Rhonda Hardin, who was sexually assaulted and strangled in Piedmont on the night of Jan. 24, 1983.

Bradley was the second Alabama Death Row inmate to be executed in a month. At the time of his step-daughter's murder, Bradley was caring for the 12-year-old girl and her younger brother, Gary Hardin Jr., while their mother was in the hospital. Alabama now has 205 Death Row inmates, all but four of them male.

Rhonda was my first child. A beautiful baby girl, born on August 15, 1970. She had a head full of black hair and blue eyes.

I was only 16 years old when I gave birth to Rhonda, and she was my pride and joy. Rhonda was a bubbly, happy child growing up. Not much brought her down. She loved children and her family, especially her little brother Gary, whom she was very protective over. She had many friends in school and all who knew her loved her and knew she was special.

But on the night of January 25, 1983 at the age of 12 years old my precious Rhonda's life was taken. "A parent's nightmare." I was in the hospital awaiting surgery when her step-dad came and told me Rhonda was missing. I told him to go to the police and make a police report.

The following morning the police came to my hospital room and told me my precious Rhonda was gone. No one who has never lost a child could even imagine the pain and hurt I felt at this time. I was left with a void inside me that I knew would never be filled.

The police said they didn't think she had been molested, because she was fully dressed with coat and leg warmers also. Snow on the ground, I thought, "God how long was my baby in the snow?" I thought of anything to relieve my hurt and pain I was feeling. The only thing at that time that was helping me was knowing the police said she had not been molested.

But that relief didn't last long. The autopsy report showed my precious Rhonda had been violated in every way possible. And now the hunt was on for the killer. But little known to me was the horror that was going to come a few months later that would change my life forever.

After a few months of investigation Rhonda's step-dad was arrested for her murder. It was like a nightmare. I said, "Dear God, NO, this just could not be". The man I had loved and married had taken one of the most precious things in my life away from me, my Rhonda.

The court proceedings were hard to go through, but by the grace of God and my family and friends, I made it through.

Her killer was convicted in July 1983 and given the death penalty. And yes, he wants to live...fighting death every step of the way. But had my Rhonda had a chance she would have said, "Please I'm only 12 years old, I want to live too. I don't want to die." But she wasn't given that chance. She wasn't given 17 years to put up a fight for her life. She died of strangulation and a blow to her head.

It's been a rough road for me and my family. I felt as though I was the only person in the world to lose a child. But now I realize many, many children's lives are taken each year by people who they know and trust.

As I finish this with tears for my child, and in closing, I would like to say, I'm not making this a death penalty issue. It is strictly an awareness and remembrance page for our murdered children. I hope you will send for your yellow ribbon in remembrance of all our murdered children across this cruel world. God bless each and everyone that visits this site. If you have any questions please email me, Judy Bennett.

UPDATE: Danny Joe Bradley was executed on February 12, 2009.

The following individuals have been executed by the State of Alabama at the Holman Correctional Facility near Atmore since 1943:

Inmate Date Method Victim

1 John Louis Evans 22 April 1983 electrocution Edward Nassar.

2 Arthur Lee Jones 21 March 1986 electrocution William Hosea Waymon.

3 Wayne Ritter 28 August 1987 electrocution Edward Nassar.

4 Michael Lindsey 26 May 1989 electrocution Rosemary Zimlich Rutland.

5 Horace Dunkins 14 July 1989 electrocution Lynn McCurry.

6 Herbert Richardson 18 August 1989 electrocution Rena Mae Callins.

7 Arthur Julius 17 November 1989 electrocution Susie Bell Sanders.

8 Wallace Thomas 13 July 1990 electrocution Quenette Shehane.

9 Larry Heath 30 March 1992 electrocution Rebecca Heam.

10 Cornelius Singleton 20 November 1992 electrocution Ann Hogan.

11 Willie Clisby 28 April 1995 electrocution Fletcher Handley.

12 Varnell Weeks 12 May 1995 electrocution Mark Batts.

13 Edward Horsley, Jr. 16 February 1996 electrocution Naomi Rolon.

14 Billy Wayne Waldrop 10 January 1997 electrocution Thurman Donahoo.

15 Walter Hill 2 May 1997 electrocution Willie Mae Hammock, John Tatum, and Lois Tatum.

16 Henry Hays 6 June 1997 electrocution Michael Donald.

17 Stephen Allen Thompson 8 May 1998 electrocution Robin Balarzs.

18 Brian K. Baldwin 18 June 1999 electrocution Naomi Rolon.

19 Victor Kennedy 6 August 1999 electrocution Annie Laura Orr.

20 David Ray Duren 7 January 2000 electrocution Kathleen Bedsole.

21 Freddie Lee Wright 3 March 2000 electrocution Warren Green and Lois Green.

22 Robert Lee Tarver, Jr. 14 April 2000 electrocution Hugh Sims Kite.

23 Pernell Ford 2 June 2002 electrocution Willie C. Griffith and Linda Gail Griffith.

24 Lynda Lyon Block 10 May 2002 electrocution Opelika Officer Roger Lamar Motley.

25 Anthony Keith Johnson 12 December 2002 lethal injection Kenneth Cantrell.

26 Michael Eugene Thompson 13 March 2003 lethal injection Maisie Carlene Gray.

27 Gary Leon Brown 24 April 2003 lethal injection Jack David McGraw.

28 Tommy Jerry Fortenberry 7 August 2003 lethal injection Ronald Michael Guest, Wilbut T. Nelson, Robert William Payne, and Nancy Payne.

29 James Barney Hubbard August 5, 2004 lethal injection Lillian Montgomery.

30 David Kevin Hocker 30 September 2004 lethal injection Jerry Wayne Robinson.

31 Mario Giovanni Centobie 28 April 2005 lethal injection Moody police officer Keith Turner.

32 Jerry Paul Henderson 2 June 2005 lethal injection Jerry Haney in Talladega and for accepting $3,000 from Haney's wife for the killing.

33 George Everett Sibley, Jr.

(common-law husband of

Lynda Lyon Block) 4 August 2005 lethal injection Opelika Officer Roger Lamar Motley.

34 John W. Peoples, Jr. September 22, 2005 lethal injection Paul Franklin, Judy Franklin, and Paul Franklin, Jr.

35 Larry Eugene Hutcherson October 26, 2006 lethal injection Irma Thelma Gray

36 Aaron Lee Jones May 3, 2007 lethal injection Carl Nelson and Willene Nelson

37 Darrell Grayson July 26, 2007 lethal injection Annie Laura Orr

38 Luther Jerome Williams August 23, 2007 lethal injection John Kirk

39 James Harvey Callahan January 15, 2009 lethal injection Rebecca Suzanne Howell

40 Danny Joe Bradley February 12, 2009 lethal injection Rhonda Hardin

Bradley v. State494 So.2d 750 (Ala.Cr.App. 1985) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted of capital murder of his stepdaughter in Circuit Court, Calhoun County, Malcolm B. Street, Jr., J., and sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Bowen, P.J., held that: (1) defendant was illegally arrested; (2) defendant's consent to search and statement to police were voluntarily given; (3) State did not have duty to disclose person to whom exculpatory confession was made; (4) evidence was sufficient to prove victim was murdered during commission of rape and sodomy; and (5) death sentence was proper in light of aggravating circumstances. Affirmed.

BOWEN, Presiding Judge.

Danny Joe Bradley was indicted for the capital murder of Rhonda Hardin, his twelve-year-old stepdaughter. A jury convicted him of two counts of a four-count indictment: murder during a rape in the first degree and murder during a sodomy in the first degree in violation of Alabama Code 1975, § 13A-5-40(a)(3). After a sentence hearing, the jury unanimously recommended the death penalty. Following a presentence investigation, the trial court held a sentence hearing and sentenced Bradley to death by electrocution. Bradley raises eight issues on this appeal from that conviction and sentence.

I

In sentencing Bradley to death, the trial court made written findings of facts. These findings are supported by the evidence.

“Upon consideration of the evidence and testimony presented before the Court during the guilt phase of the trial in this cause, the Court hereby finds as follows: “Rhonda Hardin was a twelve year old female residing at 309 Barlow Street, Apartment B in Piedmont, Calhoun County, Alabama, on January 24, 1983. The family unit residing at the above address consisted of Rhonda Hardin, her younger brother, Gary ‘Bubba’ Hardin, Judy Bradley, the mother of Rhonda and Gary; and the Defendant, Danny Joe Bradley, Judy's husband and Rhonda's and Gary's step-father.

“That on January 24th and 25th, 1983, Judy Bradley was absent from the home, having been hospitalized for some thirteen (13) days, and that the Defendant, Danny Joe Bradley, was the parental custodian of the minors, Rhonda Hardin and Bubba Hardin.

“The Bradleys (Defendant, Rhonda and Gary Hardin) were visited at their apartment on the evening of January 24, 1983, by Dianne Mobley, Jimmy Issac and Johnny Bishop who left around 8:00 p.m. and Bubba Hardin retired for the evening thereafter. When Bubba retired Rhonda was asleep on the couch in the living room. Bubba testified that Rhonda had asked him to wake her up so she could sleep in her bedroom but that Danny Bradley instructed him to leave Rhonda on the couch. Bubba testified that he was later awakened at some hour by the sound of a chair being ‘bumped’ in the kitchen and heard the unlatching of the back door; that there were no lights on and no television sound on; that he fell back asleep and was later awakened by Danny who informed him that Rhonda was missing. Danny Bradley then took Bubba next door.

“Bubba testified that Danny Bradley would play a game both with Rhonda and Bubba by having them think of something ‘good’ while Danny placed his hand on their necks and stopped the flow of blood to the brain until they were unconscious.

“Phillip Mannis resided in the adjoining duplex apartment at 309 Barlow Street and was awake watching TV until the morning hours of January 25th. At 12:50 a.m. Mannis testified that Bradley knocked on his door and stated that Rhonda Hardin was missing. Bradley told Mannis that he (Bradley) found Rhonda attempting to take some of her mother's prescription drugs; that they argued and he dozed off and on awakening found that Rhonda was gone. Mannis volunteered to help Danny Bradley find Rhonda. Danny told Mannis that he (Bradley) would first check at the house of Rhonda's grandmother (Bennett). The Defendant was gone from the Barlow Street location in his auto for ten to fifteen minutes, returned and reported to Mannis that Rhonda was not at her grandmother's house.

“Robert Roland, brother-in-law of the Defendant, testified that Danny Bradley arrived by auto at Roland's home at approximately 11:30 p.m. and asked if he had seen Rhonda. When the Defendant was told ‘no’ he walked a short distance to Ed Bennett's (his in-laws and the grandparents of Rhonda) returned and drove away.

“Ed Bennett testified that Danny Bradley arrived at his home ‘around midnight’ looking for Rhonda and upon his failure to locate her left after ten to fifteen minutes.

“Police Officer Bruce Murphy testified that he saw the Defendant in his car on North Church Street at Ladiga Street at 9:30 p.m.

“Phillip Mannis testified that Danny Bradley returned to his Barlow Street apartment around 1:15-1:20 a.m. and stated that Rhonda was not at her grandparents (the Bennetts') and asked Mannis to go with him to the Piedmont hospital to see Judy Bradley. Because of the stated fear of little gasoline in his auto, Bradley and Mannis leave on foot to look for Rhonda at approximately 1:30 a.m. and arrive around 2:00 a.m. Bradley and Mannis wait at the hospital lobby for approximately an hour to an hour and a half, as Bradley states he fears upsetting his hospitalized wife. Finally, Mannis relates to Judy Bradley that Rhonda is missing. The two men walk to the Piedmont Police Station and report the absence of Rhonda to Piedmont Police Officer Ricky Doyal at 3:30 a.m. Danny Bradley relates to the officer that he has argued with Rhonda at their home that evening, then fell asleep, and on awakening at approximately 11:30 p.m. discovered Rhonda was missing and went to his neighbors. Mannis and Bradley then walked back to the Barlow Street duplex apartment arriving between 5:00 and 5:10 a.m.

“The body of Rhonda Hardin was discovered in a wooded area approximately ten yards off McKee Street in Piedmont, Calhoun County, Alabama, at approximately 7:00 a.m. on January 25, 1983.

“At trial, evidence and testimony was produced to the effect that Rhonda Hardin was the victim of a homicide and that the death of the said Rhonda Hardin was asphyxia due to strangulation by the application of external pressure to the neck.

“The Court, from the evidence and testimony, further finds that the body of Rhonda Hardin, bore some evidence of sexual assault and that the autopsy performed indicated the presence of human semen in the vagina, rectum, mouth and gastric content of the victim.

“The Court further finds that the Defendant, Danny Joe Bradley, was transported by the police department vehicle to the Piedmont police station on January 25, 1983, at approximately 9:30 a.m. for routine questioning as the last known person to see the victim alive. At the police station the Defendant was fully advised of his legal rights and then indicated his desire to cooperate with the legal authority. During the course of that day, the Defendant consented to a search of both the apartment at 309 Barlow Street and his automobile. The Defendant further consented to the taking of his blood and saliva samples from his person as well as fingernail scrapings and a pubic hair sample. After extensive questioning throughout the day including a trip to Birmingham, Alabama, the Defendant went home to 309 Barlow Street approximately 4:00 a.m. on January 26, 1983.

Throughout the questioning of the Defendant by Piedmont City and State Law enforcement agents, the Defendant asserted that he had remained at his home until his discovery that Rhonda Hardin was absent.

“The Court further finds, from the evidence and testimony, that the defendant made the statement in the presence of Charlie Bennett and Russell Dobbs, in substance, ‘In my heart I know I done (sic) it’.

“The Court further finds, from the evidence and testimony, that the Defendant, Danny Joe Bradley, was a blood type ‘O’ non-secreter and that the semen found in and on the body of the victim was consistent with that which would be deposited by the Defendant. Further, the seminal fluids taken from the body of the victim are consistent with seminal stains found on the bed sheets in the Defendant's apartment and found on a blanket taken by the Defendant from the Piedmont hospital three days before the disappearance of the victim; that the hair, fiber and fingernail scrapings evidence clearly tended to connect the Defendant with the victim's clothing worn when discovered, with the bed sheets and blanket found inside Defendant's apartment the next morning, and fibers from the trunk of Defendant's automobile were consistent with fibers from the victim's red corduroy pants.

“The Court further finds, from the testimony of the Defendant, that the Defendant stated he lied to the legal authorities when he stated he did not leave his apartment on the night of January 24, 1983, until after his discovery that Rhonda Hardin was missing. At trial, the Defendant testified that he left the Barlow Street apartment around 10:30 p.m. on January 24, 1983, with the intent to steal a car, located on the other side of Piedmont, that he took a boys 20 inch bicycle from a yard on Hughes Street, pedaled to his intended location but determined that his opportunity to take the intended auto was not good, and that he pedaled back, returning home around midnight and discovered Rhonda Hardin was missing. The Defendant testified that he did not reveal this information earlier for fear of having his probation revoked.”

II

Bradley argues that the consent he gave to search his house and his statements to the police were the product of his illegal arrest and that, consequently, neither the physical evidence obtained from his house nor his statements should have been admitted into evidence. The resolution of this issue involves a number of related questions.

This Court must first determine whether Bradley was arrested or whether his situation was consensual. If an arrest occurred, the legality of that arrest must be determined. If the arrest was illegal, we must decide first, whether Bradley's consent to search and statements were voluntary within the confines of the Fifth Amendment, and, if so, then whether they were the tainted product of an illegal arrest and seizure. If Bradley was illegally arrested, this Court makes two determinations. First, whether the consent to search and the statements were voluntarily given within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. If the consent and statements were voluntarily given, this Court must then determine whether each was sufficiently an act of free will to purge the primary taint of the illegal arrest. United States v. Wellins, 654 F.2d 550, 552-53 (9th Cir.1981).

THE FACTS

The State's evidence shows that between 8:30 and 9:30 on the morning of January 25, 1983, approximately one hour after Rhonda's body had been discovered, four law enforcement officers arrived at Bradley's residence. Piedmont Police Officer Bruce Murphy and his partner, Officer Terry Kiser, were in plain clothes and driving a pickup truck. Piedmont Police Chief David Amberson arrived with Calhoun County Deputy Sheriff Don Glass in the Deputy's official car. Bradley was to be “picked up” for questioning because he was one of “quite a few” suspects. Officer Murphy and Chief Amberson were the only officers present that morning who testified at the suppression hearing or at trial.FN1 Both denied informing Bradley that he was under arrest. Chief Amberson testified that Bradley was not under arrest, was not placed under guard, and was free to leave anytime he wanted. Murphy testified that Chief Amberson was “in charge”, that he “was to make sure he [Bradley] was home” because Amberson was “en route to talk to him” and that he never said anything to Bradley and did not tell Bradley why he was being picked up.

FN1. Piedmont Police Office Greg Kiser testified at the suppression hearing that he was not present when Bradley was “picked up for questioning at his home.” Officer Murphy testified that he was accompanied by Officer Terry Kiser. Terry Kiser never testified.

Bradley testified that Piedmont Officers Kiser and Murphy actually told him he was “under arrest for suspicion of murder” and told him not to talk. Murphy “pushed him down against the trunk of the car and handcuffed” him, picked up his leg, looked at his foot, and told Kiser, “Yeah, that's the print we got.” Bradley testified that he was frisked outside his house before he was placed in the patrol car.

The State's evidence is inexplicitly silent as to what actually occurred when Bradley was picked up. The State's evidence does not reflect any conversation between Bradley and the police at Bradley's residence. Chief Amberson handcuffed Bradley and placed him in the Sheriff's car. Bradley was taken to City Hall where the handcuffs were removed. Bradley was handcuffed because it was the usual policy of the Piedmont Police Department to handcuff “suspects being transported.”

Bradley testified that, after he had been handcuffed and placed in a patrol car, Chief Amberson arrived and went into his apartment for two or three minutes. Amberson denied this. Bradley was taken to the police station and uncuffed. The State's evidence shows that Bradley was not placed under guard while Bradley testified that he was. Bradley was not fingerprinted or photographed, contrary to the usual practice with felony suspects being arrested.

Bradley voluntarily waived his Miranda rights. Bradley testified that “they just told me if I felt I needed a counselor, you know, that they would stop until I had one. And I told him, ‘Well, nothing to hide (sic), I don't see where I should need counsel.’ ” He was first questioned at approximately 10:00 that morning. At that time, only routine background information was obtained (name, age, date of birth, address, and employment). Around 10:50 a.m., Sergeant Gregory Kiser obtained fingernail scrapings from Bradley.

At 11:08 that same morning, Bradley signed a written “permission to search” after Sergeant Danny Bradley had read the form to him and given Bradley the opportunity to read the form himself. Immediately above Bradley's signature on this consent form appears the following paragraph: “I am giving this written permission to these officers freely and voluntarily, without any threats or promises having been made, and after having been informed by said officer that I have a right to refuse this search and/or seizure.” (Emphasis added.) Bradley testified that he signed the consent form because “Officer Murphy told me if I would cooperate that it would speed up the process and they could get through with me and, you know, go to somebody else.” Bradley also testified that he was “upset” and “couldn't really answer” whether he consented to the search because of what Officer Murphy told him or because he desired to assist the police and knew that he did not have anything to worry about. Bradley denied being told that he had a right to refuse to sign the consent form.

A statement was taken from Bradley “sometime after noon and before about four” after his house had been searched. This statement was substantially the same as what Bradley had told Officer Doyle when he had reported Rhonda's disappearance. Additionally, at trial, Bradley's account of the events of January 24th and 25th was substantially identical to the statement he gave the police. At trial, Bradley testified that he told the police the “whole” truth “up to a point” and admitted that he had lied about being home all night and that he had in fact left his house before he discovered that Rhonda was missing.

The State's evidence shows that, on the afternoon of January 25th, Bradley voluntarily agreed to go to the Department of Public Safety in Birmingham where he was given a polygraph test, the results of which are not disclosed in the record. On cross examination, Bradley testified that he went voluntarily to Birmingham because he “knew [he] didn't have anything to hide and [he was] willing to cooperate.” Bradley testified that he cooperated “as best he could.” Bradley also testified that he cooperated because he did not have anything to hide and because he had been told that the sooner he cooperated the sooner he could leave.

“Q [District Attorney]: Isn't it a fact that actually what happened on this occasion, that you cooperated with them because you felt like you didn't have anything to hide; is that not true? “A [Bradley]: I knew I didn't have anything to hide. “Q. Right. So, you cooperated with them one hundred percent; did you not? “A. They told me if I cooperated, the sooner I cooperate, the sooner I get to leave.”

Bradley was returned to his home at approximately 4:00 on the morning of January 26, 1983, approximately twenty hours after he had been picked up by the police. Chief Amberson testified that Bradley told him that he “didn't have anything to hide and wanted to stay there until he got it cleared up.” Bradley was released without being charged or placed under bond.

Medical technologist James Griffith testified that on January 26th, the day Bradley was returned home, Bradley “willingly” gave blood and saliva samples at the Piedmont Medical Clinic “about twelve o'clock” that day. Bradley testified that the police told him that he could either give them the samples or they would get a court order, so he said, “Well, I'll give it to you.” At trial, Bradley testified that he gave the blood and saliva samples of his “own free will: They asked and I obliged.”

The next day, January 27th, Bradley, while at his home, consented to a second search of his residence and signed a written permission to search. At that time, Mrs. Bradley was present and she gave the police a soiled pair of Rhonda's underwear.

Bradley returned to City Hall three or four times “under police escort.” Bradley testified, “When they would come to pick me up, I just, you know, I would go.” He was finally arrested after his indictment on March 22, 1983.

At the time Bradley was “picked up” in January of 1983, he was twenty-five years old and married. He had completed the tenth grade and worked as a carpenter and a mechanic. Bradley was no stranger to police and criminal procedure. His criminal history reveals a number of arrests. At the time of Rhonda's murder, Bradley was on probation from a 1982 conviction for burglary in the third degree.

* * *

Our review of the record convinces this Court that the evidence, although totally circumstantial, was sufficient to prove that Rhonda Hardin was murdered during the commission of a rape and sodomy.

The word “during” as used in the definition of capital offenses “means in the course of or in connection with the commission of, or in immediate flight from the commission of the underlying felony or attempt thereof.” Alabama Code 1975, § 13A-5-39.

Rhonda was twelve years old when she was strangled to death. Human semen was found in her mouth, stomach, vagina and rectum. From the expert testimony presented, the jury could have properly inferred that Rhonda engaged in sexual intercourse and deviate sexual intercourse shortly before her death. Fibers from the pants Rhonda was found wearing matched other fibers found in the trunk of Bradley's automobile. There was evidence that Rhonda usually tied her shoes in a double knot. The shoes on Rhonda's body were tied in a single knot, suggesting that someone had dressed her and that she was dead before she was dressed. Fecal, semen, and vaginal fluid stains indicated that the intercourse occurred in a bedroom in Bradley's house.

Bubba Hardin last saw his sister alive sometime after 9:00 on the night of January 24, 1983. Mr. Manus, Bradley's neighbor, was with Bradley from 12:50 to 5:30 on the morning of January 25. From this, the jury could have concluded that Rhonda must have been sexually assaulted, murdered, and disposed of between 9:00 P.M. on the 24th of January and 12:50 that following morning. Considering the ages and relationships of the parties, the nature of the offense, and the time frame within which the crime and disposal of the body must have occurred, the circumstantial evidence supports the reasonable conclusion that Rhonda was murdered during, or in the course of, or in connection with, the commission of a rape and sodomy. Taylor v. State, 442 So.2d 128 (Ala.Cr.App.1983); Potts v. State, 426 So.2d 886 (Ala.Cr.App.1982), affirmed, 426 So.2d 896 (Ala.1983). Cf. Beverly v. State, 439 So.2d 758 (Ala.Cr.App.1983).

Although an autopsy revealed no “evidence of trauma in genitalia area,” the evidence was also sufficient to show that the element of forcible compulsion was present in both the rape, § 13A-6-61, and the sodomy, § 13A-6-63. Rhonda had been strangled. She was four feet, ten and three-eighths inches tall and weighed seventy-seven pounds. She had seven wounds or bruises on her neck. Again, the totality of all the circumstances provides ample evidence to support a finding of forcible compulsion as defined by law: “Physical force that overcomes earnest resistance or a threat, express or implied, that places a person in fear of immediate death or serious physical injury to himself or another person.” Alabama Code 1975, § 13A-6-60(8). Under the principles of Dolvin v. State, 391 So.2d 133 (Ala.1980), and Cumbo v. State, 368 So.2d 871 (Ala.Cr.App.1978), cert. denied, 368 So.2d 877 (Ala.1979), there was evidence from which the jury might reasonably conclude that the evidence and all reasonable inferences therefrom excluded every reasonable hypothesis other than guilt and proof of the corpus delicti of the charged offenses.

VII

In sentencing Bradley to death, the trial court did not err in finding as an aggravating circumstance the fact that the capital offense was committed while Bradley was engaged in the commission of a rape, which is an aggravating circumstance described in § 13A-5-49(4), even though rape was an element of the capital offense charged in the indictment. § 13A-5-40(a)(3). “The fact that a particular capital offense as defined in section 13A-5-40(a) necessarily includes one or more aggravating circumstances as specified in section 13A-5-49 shall not be construed to preclude the finding and consideration of that relevant circumstance or circumstances in deterining sentence.” § 13A-5-50. Ex parte Kennedy, 472 So.2d 1106, 1108 (Ala.1985); Colley v. State, 436 So.2d 11, 12 (Ala.Cr.App.1983); Dobard v. State, 435 So.2d 1338, 1344 (Ala.Cr.App.1982), affirmed, 435 So.2d 1351 (Ala.1983), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 1063, 104 S.Ct. 745, 79 L.Ed.2d 203 (1984); Heath v. State, 455 So.2d 898, 900 (Ala.Cr.App.1983), affirmed, 455 So.2d 905 (Ala.1984), cert. granted in part, 470 U.S. 1026, 105 S.Ct. 1390, 84 L.Ed.2d 780 (1985); Jackson v. State, 459 So.2d 963, 966 (Ala.Cr.App.), affirmed, 459 So.2d 969 (Ala.1984), cert. denied, 470 U.S. 1034, 105 S.Ct. 1413, 84 L.Ed.2d 796 (1985); Julius v. State, 455 So.2d 975, 981-82 (Ala.Cr.App.1983), affirmed, 455 So.2d 984, 987 (Ala.1984), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1132, 105 S.Ct. 817, 83 L.Ed.2d 809 (1985); Ex parte Kyzer, 399 So.2d 330, 337-38 (Ala.1981).

VIII

The trial court properly found that “[t]he capital offense was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel compared to other capital offenses.” § 13A-5-49(8). This aggravating circumstance “was intended to apply to only those conscienceless or pitiless homicides which are unnecessarily torturous to the victim.” Ex parte Kyzer, 399 So.2d 330, 334 (Ala.1981). In Hill v. State, 422 So.2d 816 (Fla.1982), cert. denied, 460 U.S. 1017, 103 S.Ct. 1262, 75 L.Ed.2d 488 (1983), the twenty-two-year-old defendant strangled a twelve-year-old girl after raping her. After the murder, the defendant showed the body to a friend and boasted, “She wouldn't give it up, so I had to take it.” 422 So.2d at 817. The Florida Supreme Court held: “The record shows that appellant committed the rape and murder in such a fashion to make it especially heinous, atrocious, and cruel.” Id. at 819.

The State of Georgia has a similar aggravating circumstance which provides, “The offense of murder ... was outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible, or inhuman in that it involved torture, depravity of mind, or aggravated battery to the victim.” Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1(b)(7). In Phillips v. State, 250 Ga. 336, 340, 297 S.E.2d 217, 221 (1982), the Georgia Supreme Court held, “[t]orture may be found where the victim is subjected to serious physical, sexual, or psychological abuse before death.” In the earlier case of Hance v. State, 245 Ga. 856, 861, 268 S.E.2d 339, 345, cert. denied, 449 U.S. 1067, 101 S.Ct. 796, 66 L.Ed.2d 611 (1980), that same Court held, “[t]orture occurs when the victim is subjected to serious physical abuse before death. Godfrey v. Georgia, [446] U.S. [420] p. 431-32, 100 S.Ct. [1759] p. 1766 [64 L.Ed.2d 398 (1980)]. Serious sexual abuse may be found to constitute serious physical abuse. House v. State, 232 Ga. 140, 145-47, 205 S.E.2d 217, 221-222 (1974), cert. denied, 428 U.S. 910, 96 S.Ct. 3221, 49 L.Ed.2d 1217 (1976).” In House, the Georgia Supreme Court found that the death penalty was not excessive or disproportionate on the conviction of a defendant on two counts of having murdered children after committing acts of sodomy upon them.

This Court has no difficulty in independently determining that this capital offense was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel compared to other capital offenses. In Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584, 97 S.Ct. 2861, 53 L.Ed.2d 982 (1977), the Supreme Court of the United States held that the sentence of death for the crime of the rape of an adult woman was grossly disproportionate and constituted excessive punishment forbidden by the Eighth Amendment as cruel and unusual punishment. In so doing, the court commented on the seriousness of the crime:

“We do not discount the seriousness of rape as a crime. It is highly reprehensible, both in a moral sense and in its almost total contempt for the personal integrity and autonomy of the female victim and for the latter's privilege of choosing those with whom intimate relationships are to be established. Short of homicide, it is the ‘ultimate violation of self.’ It is also a violent crime because it normally involves force, or the threat of force or intimidation, to overcome the will and the capacity of the victim to resist. Rape is very often accompanied by physical injury to the female and can also inflict mental and psychological damage. Because it undermines the community's sense of security, there is public injury as well.” 433 U.S. at 597-98, 97 S.Ct. at 2869, 53 L.Ed.2d 982.

Here, Rhonda was not only raped but she was sexually abused and strangled to death. Rhonda was not an adult but a twelve-year-old child. Her assailant was her twenty-two-year-old stepfather. The especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel aggravating circumstance was warranted and fully justified in this case.

IX

This section deals with the extent of the appellate review required in a case where the death penalty has been imposed. This Court has searched the entire record on appeal and has found no plain error or defect which has or probably has adversely affected any substantial right of Bradley. A.R.A.P. Rule 45A. There is no evidence in the record to indicate that the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor. Alabama Code 1975, § 13A-5-53(b)(1).

An independent weighing of the aggravating and mitigating circumstances convinces this Court that death is the proper sentence. § 13A-5-53(b)(2).

Considering both the crime and the defendant, the sentence of death is neither excessive nor disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases. Dunkins v. State, 437 So.2d 1349 (Ala.Cr.App.), affirmed, 437 So.2d 1356 (Ala.1983), cert. denied, 465 U.S. 1051, 104 S.Ct. 1329, 79 L.Ed.2d 724 (1984) (rape-intentional killing/death); Potts v. State, 426 So.2d 886 (Ala.Cr.App.1982), affirmed, 426 So.2d 896 (Ala.1983) (carnal knowledge-intentional killing/life without parole); See also Bell v. State, 461 So.2d 855 (Ala.Cr.App.1984) (sexual abuse-murder/life without parole); Johnston v. State, 455 So.2d 152 (Ala.Cr.App.1984) (sexual abuse-murder/life without parole).

The trial court found the existence of two aggravating circumstances: The capital offense (1) was committed while the defendant was engaged in the commission of, or flight, after committing or attempting to commit, rape, specifically rape in the first degree, § 13A-5-49(4), and (2) was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel compared to other capital offenses, § 13A-549(8). The trial court did not find the existence of any statutory mitigating circumstance. § 13A-5-51. The trial court did note that it had “considered the evidence and testimony presented to the jury and to the Court in regard to the Defendant's background and character as the same pertains to the mitigating circumstances that should be properly considered by the Court.” An independent review convinces this Court that the trial court's findings concerning the aggravating and mitigating circumstances are supported by the evidence.

Review convinces this Court that Danny Joe Bradley received a fair trial and that his conviction of a capital offense and sentence to death are proper and due to be affirmed. AFFIRMED.

Bradley v. State557 So.2d 1339 (Ala. Cr. App 1989) (PCR).

Defendant was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death by the Circuit Court, Calhoun County, Malcolm B. Street, Jr., J., and defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, 494 So.2d 750, affirmed. On petition for review, the Supreme Court, 494 So.2d 772, affirmed. Thereafter, defendant filed petition for postconviction relief, which was denied by the Circuit Court, and defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Bowen, J., held that: (1) prosecution's failure to disclose certain information to defendant did not constitute Brady, violation, and (2) material did not qualify as newly discovered evidence. Affirmed.

BOWEN, Judge.

This is an appeal from the circuit court's denial of a petition for post-conviction relief.

In 1983, Danny Joe Bradley was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death. That conviction and sentence were affirmed on direct appeal. Bradley v. State, 494 So.2d 750 (Ala.Cr.App.1985), affirmed, Ex parte Bradley, 494 So.2d 772 (Ala.1986), cert. denied, Williams v. Ohio, 480 U.S. 923, 107 S.Ct. 1385, 94 L.Ed.2d 699 (1987).

In 1987, Bradley filed a pro se petition for post-conviction relief under Rule 20, A.R.Cr.P. Temp. After appointment of counsel, Bradley filed two amended petitions. Following four evidentiary hearings, the petition was denied. On this appeal from that denial, Bradley raises two issues: (A) that, pursuant to Rule 20.1(a), he was denied his due process right to a fair trial because of the State's failure to disclose four items of exculpatory evidence prior to his trial as required by Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 83 S.Ct. 1194, 10 L.Ed.2d 215 (1963), and (B) that, pursuant to Rule 20.1(e), this exculpatory material qualifies as newly discovered evidence, entitling him to a new trial.

I

Bradley claims that the State withheld the following four items of exculpatory information from him: (1) an alleged confession to the murder of the victim, Rhonda Hardin, by Ricky McBrayer; (2) a similar confession by Keith Sanford, (3) a police file “note” implicating Ricky Maxwell, and (4) forensic test results which were either invalid or inconsistent with the conclusion that Bradley alone had sexual contact with the victim prior to her death.

(1) The McBrayer Confession

Bradley's first claim, that the State failed to disclose the existence of a confession by Ricky McBrayer to one Glenn “Coffee” Burns, is procedurally barred from review here. The failure to disclose the alleged McBrayer confession was raised on motion for new trial in 1983 and was addressed by this court on direct appeal in 1985. See Bradley v. State, 494 So.2d at 767-68. “A petitioner will not be given relief under [Rule 20] based upon any ground ... [w]hich was raised or addressed on appeal or in any previous collateral proceeding....” Rule 20.2(a)(4), A.R.Cr.P. Temp.

Furthermore, with regard to the McBrayer confession, the trial judge made the following findings of fact in his order of January 9, 1989, denying the petition:

“At the hearing on this petition, Burns testified as he did at the hearing on the motion for a new trial. Former Piedmont Police Chief David Amberson testified that McBrayer had never confessed to any police officer and there was no reason to arrest McBrayer in connection with the murder of Rhonda Hardin. Amberson had previously testified at the motion for new trial hearing that he had instructed former ABI Agent Dave Dothard and former Piedmont Police Officer Charles Brown to investigate the possibility that McBrayer had been involved in the murder, and that this investigation disclosed that McBrayer was not involved. (R. 478-479)

“Former detective sergeant Charles Brown testified in a deposition, which was stipulated into evidence, that his investigation led him to rule McBrayer out as a suspect in the murder of Rhonda Hardin. Brown also testified that he was aware of ‘hard feelings' between Burns and McBrayer at the time Burns made his report to police. Brown testified that he was suspicious of Burns' claim when it was first brought to the police. Brown also testified that McBrayer denied being involved in any way with the murder when questioned following Burns' claim.

“District Attorney Robert Field testified at the evidentiary hearing that there were numerous rumors circling around the community at the time of the offense as to who might have been involved in the murder. Field testified that McBrayer's name came up along with others prior to discovery of all the evidence in the case.

“Rickey McBrayer testified at the evidentiary hearing that the night of the murder, he was at the LaMont Motel in Piedmont with friends. He then traveled into Georgia with a couple of people for about thirty minutes before returning to Piedmont, at about dark. McBrayer testified that he did not know Rhonda Hardin, he was not present when she was killed, and he never told Burns that he killed her. He recalled being questioned by the police some time after the murder. McBrayer testified that he was never alone the night of the murder.

“This Court notes that the parties stipulated into evidence a forensic report that indicates that McBrayer has Type A blood and is a secretor. Based on the forensic evidence presented at petitioner's capital murder trial, McBrayer would have been in the same forensic classification as Gary Hardin, Jimmy Issac, Phillip Manis and Johnny Bishop. (R. 258-259). Consequently, McBrayer would not be a likely suspect in the rape/sodomy of Rhonda Hardin. Petitioner was tested prior to trial and shown to be a non-secretor. (R. 259)

“This Court further finds, after considering the testimony and evidence presented, that there is no merit to Burns' claim that McBrayer confessed to him. This Court finds Burns to be not credible and truthful based on the testimony presented at trial, the hearing on the motion for a new trial and the hearing on this petition. Where Burns' testimony conflicts with that of Amberson and Brown, this Court accepts the testimony of the two former Piedmont police officers as credible and truthful.

“In addition, this Court specifically finds that the Piedmont Police Department did not improperly conceal Burns' identity from trial counsel or improperly inform trial counsel that the confession had been investigated and proved groundless. The appellate courts have affirmed on the disclosure issue and the evidence presented at the evidentiary hearing clearly established that the alleged confession was groundless.”

(2) The Sanford Confession

Bradley's second amended petition contained the following allegation: “That a person by the name of ‘Keith Sanford’ told an unnamed informant that ‘we killed Rhonda, and I'll kill you.’ This statement was allegedly made while the said Keith Sanford was intoxicated and while he held a knife to the unnamed informant. This information was reported to the Piedmont Police Department on or about February 15, 1983, but was not reported to the Petitioner's Attorneys upon their request for exculpatory material. Such failure to divulge such information violated Petitioner's right to a fair trial and to due process of law.”

In his order denying the petition, the trial court made the following findings of fact regarding this claim:

“Former [Piedmont] investigator Brown testified that an anonymous nineteen-year-old female contacted him by telephone approximately three weeks after the murder and told him that she was in a position of sexual intimacy with Sanford and at some point in the progression of that intimacy she had a change of heart and did not wish to proceed with the act. In an effort to persuade her to continue, Sanford allegedly threatened her with a knife and said he was responsible for Rhonda's death in an effort to coerce her. Brown questioned Sanford about this allegation on two or three occasions, but was unable to develop any information of a ‘confirmable nature’ linking Sanford to the crime or crime scene. Brown had no further contact with the anonymous informant. Brown therefore dismissed Sanford as a suspect in the murder of Rhonda Hardin.

“A Piedmont Police Department form, Respondent's Exhibit 1 attached to Brown's deposition, indicates that Sanford gave police an alibi for the night of the murder. Sanford testified at the evidentiary hearing that he informed police of his whereabouts the night of the murder. Sanford's testimony was consistent with the information in the police form. Sanford denied knowing the victim or being involved in her death. Sanford denied ever telling anyone that he killed Rhonda Hardin.

“Former ABI investigator Dave Dothard testified that Sanford was not a suspect in the murder. Dothard testified that there was no evidence that Sanford was involved in the murder. Former investigator Brown also testified that Sanford was dismissed as a possible suspect because the investigative leads regarding any speculation on his involvement in the crime had been followed to their fullest extent and had not developed any concrete evidence. Brown said that there were no more leads to be followed regarding Sanford.

“After considering the evidence and hearing the testimony, this Court finds that the allegation concerning Sanford is without merit. There existed no evidence to connect Sanford with the murder. An anonymous phone call without any substantiation was not enough to make Sanford a suspect in this case. The evidence indicates that the police checked Sanford's alibi and dismissed him as a possible suspect after investigation. This Court will not grant relief as to this allegation.”

“In order to establish a Brady violation, the defendant must prove (1) The prosecution's suppression of evidence; (2) the favorable character of the suppressed evidence for the defense; (3) the materiality of the suppressed evidence. Monroe v. Blackburn, 607 F.2d 148, 150 (5th Cir.1979) cert. denied, 446 U.S. 957[, 100 S.Ct. 2929, 64 L.Ed.2d 816] (1980). See Moore v. Illinois, 408 U.S. 786, 92 S.Ct. 2562, 33 L.Ed.2d 706 (1972); Killough v. State, 438 So.2d 311, 316 (Ala.Cr.App.1982), rev'd on other grounds, Ex parte Killough, 438 So.2d 333 (Ala.1983).” Sexton v. State, 529 So.2d 1041, 1045 (Ala.Cr.App.1988). “Pursuant to United States v. Bagley, 473 U.S. 667, 105 S.Ct. 3375, 87 L.Ed.2d 481 (1985), undisclosed evidence is material under the Brady rule ... only when it is reasonably probable that the outcome of the trial would have been different had the evidence been disclosed to the defense.” Hamilton v. State, 520 So.2d 155, 159 (Ala.Cr.App.1986) Ex parte Hamilton, 520 So.2d 167 (Ala.1987), cert. denied, 488 U.S. 871, 109 S.Ct. 180, 102 L.Ed.2d 149 (1988).

“Even where there is total nondisclosure of information the test is whether the use of the information at trial would have changed the result by creating a reasonable doubt where one did not otherwise exist. United States v. Agurs, 427 U.S. 97, 96 S.Ct. 2392, 49 L.Ed.2d 342 (1976); Jones v. State, 396 So.2d 140 (Ala.Cr.App.1981). As the United States Supreme Court stated in Beck v. Washington, 369 U.S. 541, 558, 82 S.Ct. 955, 964, 8 L.Ed.2d 98 (1962):

“ ‘While this Court stands ready to correct violations of constitutional rights, it also holds that it is not asking too much that the burden of showing essential unfairness be sustained by him who claims such injustice and seeks to have the result set aside, and that it be sustained not as a matter of speculation but as a demonstrable reality.’ ” Parker v. State, 482 So.2d 1336, 1340-41 (Ala.Cr.App.1985).

Bradley's argument that the nondisclosure of Keith Sanford's name as one of a number of possible suspects in this murder case denied him due process bears striking resemblance to the argument made by the petitioner, and rejected by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, in Jarrell v. Balkcom, 735 F.2d 1242 (11th Cir.1984), cert. denied, 471 U.S. 1103, 105 S.Ct. 2331, 85 L.Ed.2d 848 (1985):

“While investigating the murder, the police investigated various leads and came up with several ‘possible suspects.’ Petitioner contends that a Brady violation occurred because the defense and the jury had a right to know the names and evidence concerning these other suspects. The respondent contends that these ‘possible suspects' were not readily identifiable, in that these ‘possible suspects' were merely talked to by the police to see what possible information they might have; none of these persons were suspects in the sense that the investigation actually focused on them.

“ Brady requires the prosecution to produce evidence that someone else may have committed the crime. See Sellers v. Estelle, 651 F.2d 1074 (5th Cir.1981). In comparison with the other suspect in Sellers, the ‘other suspects' in the instant case were ephemeral. In Sellers, police reports indicated that another person had actually admitted committing the crime with which defendant was charged. Id. at 1075. In the instant case, police reports listed hundreds of possible suspects. Finding a Brady violation under these circumstances would be tantamount to requiring the government to turn over their entire investigation. Because Brady created no such general constitutional right to discovery, see Weatherford v. Bursey, 429 U.S. 545, 559-60, 97 S.Ct. 837, 845-46, 51 L.Ed.2d 30 (1977), petitioner has failed to show a due process violation.” 735 F.2d at 1258.

As the trial court's findings of fact indicate, Bradley failed to show that the nondisclosure of unsubstantiated rumor linking Keith Sanford to the offense for which Bradley was convicted would have altered the outcome of Bradley's trial.

(3) The Ricky Maxwell Note

Bradley's second amended petition also alleged: “That investigators from the Piedmont Police Department and the Alabama Bureau of Investigation were given a note from Danny Smith, an investigator with the Cherokee County District Attorney's Office, on or about May 12, 1983, which note stated, ‘Rickey Maxwell killed Rhonda-Piedmont, AL.’ Said note or information contained thereon was not reported to the Petitioner's Attorneys upon their request for exculpatory material. Such failure to divulge such information violated Petitioner's right to a fair trial and to due process of law.”

With regard to this claim, the trial court entered the following findings:

“[Former ABI Investigator Dave] Dothard testified that Smith gave the note, Petitioner's Exhibit B, to himself and Brown. On May 16, 1983, Dothard interviewed Anita Beecham about the note she had written. Beecham was Maxwell's former girlfriend and they had been living together. Prior to her writing the note Maxwell had beaten Beecham. Beecham told Dothard that Maxwell had introduced her to petitioner and that Maxwell and petitioner would ‘go off alone together and talk.’ Beecham could provide Dothard with no evidence to connect Maxwell to the murder, other than her ‘intuition.’ Dothard testified that there was no evidence that Maxwell had any involvement in the murder of Rhonda Hardin. According to Dothard, Maxwell was not a suspect. Dothard testified that the note would not make Maxwell a suspect because ‘anyone can write a note.’

“Based on the evidence presented at the hearing, this Court finds no merit to this allegation. The police, within four days of receiving petitioner's Exhibit B, interviewed its author, Beecham, to determine whether she had any information concerning the murder. After the interview the police determined that there was no evidence to implicate Maxwell and Hardin. This allegation is without merit as the police promptly checked into the claim and determined it to be without basis. This Court finds no prejudice to any of petitioner's rights.”

The materiality analysis we set out in dealing with the Keith Sanford evidence is equally applicable here. There was simply no reasonable probability that, had the Ricky Maxwell note been disclosed to the defense, the outcome of the trial would have been different.

The trial court's finding that the claim was “baseless” is supported by testimony presented at the evidentiary hearings, which established that police investigators received hundreds of leads, followed them to the extent possible, and, without evidence corroborating their tips, dismissed many individuals as suspects.

The District Attorney testified: “In a case like this, it's highly volatile and highly publicized. Law enforcement officials are barraged with calls about, you know, so-and-so did it or this one did it. In this case, my recollection is they ran down every one of those leads to determine whether or not there was any credulence to that theory.”

Defense counsel Ralph Brooks testified as follows: “Q. Mr. Brooks, would it be a fair statement to say that as you were preparing for trial in this case that the Piedmont community was overrun with rumors concerning who actually killed Rhonda Hardin? “A. I would say that was a fair statement. “Q. And you received information from numerous individuals about possible suspects in this case? “A. Yes, sir. “Q. Did you attempt to locate or run down each one of these suspects in this case? “A. Now-I recall now that you mention it, I had a check list that I saw the other day, that I had 47 different names on it that I had checked off as running down possible items on. Most of them turned out to be absolutely nothing to them. They would get-there would be no substance to them. It would be a rumor that so and so knew this and told me this, but when you got back to the source of the rumor, it was always, ‘No, I never said that.’ It would go nowhere.”

Under the circumstances, Keith Sanford and Ricky Maxwell were not “suspects in the sense that the investigation actually focused on them.” Jarrell v. Balkcom, 735 F.2d at 1258. The Sanford and Maxwell leads, based on unconfirmed hearsay and dismissed after investigation, were, as the Eleventh Circuit characterized it, “ephemeral.” Id. These ephemeral leads, at most, amounted to “a matter of speculation” rather than a “demonstrable reality,” see Beck v. Washington, supra ( quoted in Parker v. State, 482 So.2d at 1341), that Bradley's trial was unfair. Thus, Bradley did not sustain his burden of proving that, had he known of either lead prior to trial, the result of the proceeding would have been different.

(4) The Forensic Serology Test Inconsistency

Bradley alleged in his petition that “an investigator for the Piedmont Police Department was orally informed by the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences that certain test results were invalid or inconsistent with other, controlled test results. This information was not contained in the written documentation of the laboratory test reports used at the Petitioner's trial. Such failure to divulge such inconsistencies in the test results to Petitioner's Attorneys or in the written lab reports constitutes a fraud perpetrated upon the Petitioner and the Court by the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences and the Piedmont Police Department, and as the forensic evidence was a material factor in the conviction of the Petitioner, the Petitioner was denied fairness and due process of law.”

The trial court made the following findings on this claim:

“Petitioner introduced at the evidentiary hearing a handwritten note from the Piedmont Police file, Petitioner's Exhibit # 2, which was dated February 9, 1983 and entitled ‘Re: Telephone Conversation with Fay Ogletree.’ The note details some forensic serology information apparently involving the examination of the victim.

“Some of the information in this note is consistent with Faye Ogletree's report of March 2, 1983, but petitioner relies upon that portion of the note that states:

“ ‘B and H factor both remain or diminish together. In this case the H stayed and the B vanished with dilution. This is not consistent with controlled test results.’ ”

There is no indication on the face of the exhibit to further explain the above-quoted portion and petitioner presented no evidence as to who wrote this note or whether it was actually based on a conversation with anyone from the Department of Forensic Sciences.

“[District Attorney] Field testified that all Ogletree's forensic reports were turned over to trial counsel. Field did not know who wrote this exhibit. Field testified that he spent two days prior to petitioner's trial talking with Ogletree about her report, but now, more than five years later he could not recall the details of her expert testimony. [Defense Counsel] Brooks testified that he had lengthy conversations with Ogletree prior to trial and discussed this particular point or something very similar. [Defense Counsel] Dick testified that he went with Brooks to meet Ogletree in Birmingham and they reviewed the reports for several hours with her. Dick testified that Brooks was more familiar with forensic testimony, but that he could not say that this exhibit conflicted with the reports that were provided to them prior to trial.

“Petitioner presented no evidence to indicate that the information contained in this exhibit conflicted in any way with the lab reports presented to trial counsel by Faye Ogletree. In fact the testimony at the hearing indicated that trial counsel covered this point with Ogletree prior to trial. The exhibit itself may explain the alleged problem when it states:

“ ‘B group found in rectum and vagina may not be a factor. Reading may be a fluke due to the bacterial activity in those two body cavities.’ ”

Ogletree's final report was issued almost one month after the date on this exhibit, and the exhibit itself refers to certain ‘body fluid examinations' that were not completed at the time this exhibit was written. Ogletree's testimony, (R. 247-286), indicates that Rhonda Hardin was a secretor, while the exhibit states that there was at that time only a preliminary indication as to her blood type and antigen analysis.

“This Court finds as a fact that this allegation does not constitute newly discovered evidence. Trial counsel indicated a familiarity with the information, and there is no apparent inconsistency between the exhibit and the evidence disclosed to trial counsel and presented at trial.”

The trial court's finding that defense counsel “discussed this particular point or something very similar” with forensic serologist Faye Ogletree prior to trial is supported by the evidence and leads to the conclusion that “[t]rial counsel indicated a familiarity with the information, and there is no apparent inconsistency between the exhibit and the evidence disclosed to trial counsel and presented at trial.”