56th murderer executed in U.S. in 2005

1000th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

5th murderer executed in North Carolina in 2005

39th murderer executed in North Carolina since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

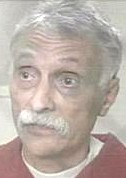

Kenneth Lee Boyd W / M / 40 - 57 |

Thomas Dillard Curry W / M / 57 Julie Curry Boyd W / F / 36 |

Estranged Wife |

07-14-94 |

Summary:

Boyd and his wife Julie had an extremely stormy marriage for 13 years before Julie left and moved herself and her children in with her father. Boyd repeatedly stalked Julie, once handing one of their sons a bullet and a note to give his mother that said the bullet was intended for her. On March 4, 1988 Boyd drove around with his boys, telling them that he was going to go and kill everyone at his father-in-law's home. When they arrived, he entered the home and shot and killed both his wife and her father with a .357 Magnum pistol. One of Julie's sons was pinned under his mother's body as Boyd continued to fired at her. The child scrambled out from beneath his mom's body and wriggled under a nearby bed to escape the hail of bullets. When Boyd tried to reload the pistol, another son tried to grab it. Boyd went to the car, reloaded his gun, came back into the house and called 911, telling the emergency operator, "I've shot my wife and her father - come on and get me." Then more gunshots can be heard on the 911 recording. Law enforcement officers arrived and as they approached, Boyd came out of the nearby woods with his hands up and surrendered to the officers. Later, after being advised of his rights, Boyd gave a lengthy confession

Citations:

State v. Boyd, 332 N.C. 101, 418 S.E.2d 471 (N.C. 1992) (Direct Appeal).

State v. Boyd, 343 N.C. 699, 473 S.E.2d 327 (N.C. 1996) (Retrial Direct Appeal).

Final Meal:

A medium-well New York strip steak, a baked potato with sour cream, a roll with butter, a salad with ranch dressing and a Pepsi.

Final Words:

"I was just going to ask Kathy, my daughter-in-law, to look after my son and my grandchildren. God bless everybody in here."

Internet Sources:

BOYD, KENNETH LEE

DOC Number: 0040519

DOB: 01/19/1948

RACE: WHITE

SEX: MALE

DATE OF SENTENCING: 07/14/1994

COUNTY OF CONVICTION: ROCKINGHAM COUNTY

FILE#: 88001742

CHARGE: MURDER FIRST DEGREE (PRINCIPAL)

DATE OF CRIME: 07/28/1990

North Carolina Department of Correction (Chronology / Press Release)

Kenneth Lee Boyd - Chronology of Events

10/13/2005 - Correction Secretary Theodis Beck sets November 18, 2005 as the execution date for Kenneth Boyd.

10/3/2005 - U.S. Supreme Court denies Boyd's petition for a writ of certiorari.

7/31/1996 - North Carolina Supreme Court confirms Boyd's conviction and sentence of death.

7/14/1994 - Kenneth Lee Boyd sentenced to death in Rockingham Co. Superior Court for the murders of Thomas Dillard Curry and Julie Curry Boyd.

North Carolina Department of Correction

For Release: IMMEDIATE

Contact: Public Affairs Office

Date: Oct 13, 2005

Phone: (919) 716-3700

Execution date set for Kenneth Lee Boyd

RALEIGH - Correction Secretary Theodis Beck has set Dec. 2, 2005 as the execution date for inmate Kenneth Lee Boyd. The execution is scheduled for 2 a.m. at Central Prison in Raleigh.

Boyd, 57, was sentenced to death July 14, 1994 in Rockingham County Superior Court for the March 1988 murders of Julie Curry Boyd and Thomas Dillard Curry.

Central Prison Warden Marvin Polk will explain the execution procedures during a media tour scheduled for Monday, November 28 at 10:00 a.m. Interested media representatives should arrive at Central Prison’s visitor center promptly at 10:00 a.m. on the tour date. The session will last approximately one hour.

The media tour will be the only opportunity to photograph the execution chamber and deathwatch area before the execution. Journalists who plan to attend the tour should contact the Department of Correction Public Affairs Office at (919) 716-3700.

"N.C. man is 1,000th executed," by Estes Thompson. (Associated Press Posted on Fri, Dec. 02, 2005)

RALEIGH -- A double murderer who said he didn't want to be known as a number became the 1,000th person executed in the United States since capital punishment resumed 28 years ago. Kenneth Lee Boyd, who brazenly gunned down his estranged wife and father-in-law 17 years ago in Rockingham County near the N.C.-Virginia border, died at 2:15 a.m. this morning after receiving a lethal injection. The 1,001st execution also could take place in the Carolinas -- this evening in South Carolina.

After watching Boyd die, Rockingham County Sheriff Sam Page said the victims should be remembered. "Tonight, justice has been served for Mr. Kenneth Boyd," Page said.

Boyd's death rallied death penalty opponents, and about 150 protesters gathered outside the prison. "Maybe Kenneth Boyd won't have died in vain, in a way, because I believe the more people think about the death penalty and are exposed to it, the more they don't like it," said Stephen Dear, executive director of People of Faith Against the Death Penalty. "Any attention to the death penalty is good because it's a filthy, rotten system," he said.

Boyd, 57, did not deny killing Julie Curry Boyd, 36, and her father, 57-year-old Thomas Dillard Curry. But he said he thought he should be sentenced to life in prison, and he didn't like the milestone his death would mark. "I'd hate to be remembered as that," Boyd told The Associated Press on Wednesday. "I don't like the idea of being picked as a number."

The Supreme Court in 1976 ruled that capital punishment could resume after a 10-year moratorium. The first execution took place the following year, when Gary Gilmore went before a firing squad in Utah.

During the 1988 slayings, Boyd's son Christopher was pinned under his mother's body as Boyd unloaded a .357-caliber Magnum into her. The boy pushed his way under a bed to escape the barrage. Another son grabbed the pistol while Boyd tried to reload. The evidence, said prosecutor Belinda Foster, clearly supported a death sentence. "He went out and reloaded and came back and called 911 and said 'I've shot my wife and her father, come on and get me.' And then we heard more gunshots. It was on the 911 tape," Foster said.

In the execution chamber, Boyd smiled at daughter-in-law Kathy Smith -- wife of a son from Boyd's first marriage -- and a minister from his home county. He asked Smith to take care of his son and two grandchildren and she mouthed through the thick glass panes separating execution and witness rooms that her husband was waiting outside. In his final words, Boyd said: "God bless everybody in here."

Boyd's attorney Thomas Maher, said the "execution of Kenneth Boyd has not made this a better or safer world. If this 1,000th execution is a milestone, it's a milestone we should all be ashamed of. In Boyd's pleas for clemency, his attorneys said he served in Vietnam where he operated a bulldozer and was shot at by snipers daily, which contributed to his crimes. Both Gov. Mike Easley and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene.

Execution No. 1,001 was scheduled for 6 p.m. tonight, when South Carolina planned to put Shawn Humphries to death for the 1994 murder of a store clerk.

"N.C. executes nation's 1,000th inmate since '76; Kenneth Lee Boyd, sentenced to die by lethal injection, spends final night in Central Prison," by Andrea Weigl and Cindy George. (Dec 02, 2005 06:41 AM)

North Carolina's execution of Kenneth Lee Boyd this morning would have happened quietly, but numerical circumstance made him the 1,000th inmate put to death in the United States since capital punishment resumed. The number brought international attention to Raleigh's Central Prison.

A jury sentenced Boyd to death for killing his estranged wife and father-in-law in 1988. Two of the victims' relatives planned to watch as prison officials injected a series of lethal drugs into Boyd's veins; others had said he deserved to die for his crimes.

As the 2 a.m. death hour approached, hundreds of death penalty opponents protested outside the prison and about 20 were arrested. National leaders in the anti-death penalty movement spoke to the crowd. Reporters from international wire services and local television stations alike were on hand. Former North Carolina death row inmate Alan Gell was among the protesters, wearing a red T-shirt that said: "Innocent. N.C. Department of Correction Death Row." He told those gathered that he was friendly with Boyd in prison. "I want to hope and pray that Kenneth Boyd be not remembered as the 1,000th person executed. I hope he is remembered as Kenneth Boyd -- not a number, but a human being," said Gell, who was acquitted of a murder charge after a retrial.

Boyd, 57, was thrust into this spotlight Tuesday when Virginia Gov. Mark R. Warner granted clemency to Robin Lovitt, who had been scheduled for execution Wednesday. With that decision, Warner sent the death penalty protesters and media attention south along Interstate 95. News accounts about the anticipated 1,000th execution appeared on Agence France-Presse, a French wire service; China Daily, a national English language newspaper; and the Guardian in London.

On Thursday, Boyd visited all day with one of his sons. At 5 p.m., he ate his last meal: a medium-well New York strip steak, a baked potato with sour cream, a roll with butter, a salad with ranch dressing and a Pepsi. At close to 6 p.m., the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Boyd's last legal appeals based on claims of juror misconduct and bias.

At 10 p.m. Thursday, Gov. Mike Easley denied Boyd's request for clemency. "I find no compelling reason to grant clemency and overturn the unanimous jury verdicts affirmed by the state and federal courts," Easley said in a statement.

The protesters lined Western Boulevard holding candles and signs as a slight rain fell and the temperature dropped to 45 degrees. One held a large white cross. Another held a large yellow peace sign. At the end of the sidewalk stood a hangman's gallows. At 11:27 p.m., about 20 protesters tried to get to the prison to stop the execution. The group dashed past the line of officers standing guard at the top of the prison's driveway. A few got as far as 15 feet down the driveway. As police stopped them, other protesters clapped, cheered and sang "We Shall Overcome." Police soon handcuffed the arrestees and loaded them into a bus and a police van for the ride to the Wake County jail.

The protest marked a moment that took almost three decades to arrive. In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty as unconstitutional, ruling that states meted out the punishment arbitrarily. Four years later, the court validated several states' rewritten death penalty laws. Executions resumed in January 1977 when a Utah firing squad killed Gary Gilmore. North Carolina's first execution was in 1984, when James W. Hutchins died for killing three law officers. Almost 1,500 people died at the hands of the inmates executed during the past 28 years, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

The 1,000th execution occurred amid national debate over capital punishment. Fewer killers are being sentenced to death and fewer are being executed. Some states have been roiled by evidence that innocents end up on death row. "Jurors are starting to question the death penalty," Boyd's lawyer, Thomas Maher of Chapel Hill, told those gathered Thursday evening.

By 2001, a slim majority of Americans -- 53 percent of people questioned in a Gallup poll -- said they supported a moratorium until the administration of the death penalty could be evaluated. Illinois passed a moratorium on the death penalty in 2000 after 13 convicted men were exonerated. For several years, North Carolina has been debating a two-year moratorium on executions. That campaign has so far faltered. The state Senate approved a moratorium in 2003, but it never came up in the House. This summer, a moratorium bill again failed to get a vote on the House floor.

Instead, House Speaker Jim Black, a Democrat from the Charlotte area, appointed a 22-member committee to consider whether the death penalty is being applied fairly in North Carolina. It meets for the first time Dec. 19. "My hope is to recommend some changes in the law to make the capital punishment process more fair, minimize the chances of any innocent person getting caught up in it and look at issues of proportionality and racial discrimination," said Rep. Joe Hackney, a Chapel Hill Democrat and committee co-chairman.

Branny Vickory, president of the N.C. Conference of District Attorneys, which opposed the select committee's creation, questions what more needs to be studied. Vickory points out that prosecutors supported past changes to the system -- outlawing the death penalty for the mentally retarded and having prosecutors agree to share all their evidence and open their files to defense lawyers before trial. "We're running around in a lot of different directions, looking at the procedures, when the real issue is whether we want a death penalty," said Vickory, the prosecutor in Wayne County. The General Assembly will take up the committee's recommendations when it reconvenes in spring.

Meanwhile, the United states will leave Boyd's landmark death behind quickly. The 1,001st execution is set today in South Carolina. Shawn Humphries, who killed a store clerk, is scheduled to die at 6 p.m.

Kenneth Lee Boyd Kenneth Lee Boyd, 57, was set to be executed at 2 a.m. today for the March 1988 shootings of his wife, Julie Boyd, and her father, Thomas Dillard Curry.

THE CRIME: Prosecutors say Boyd went on a rampage inside the Rockingham County home. They say he stalked his estranged wife through the house, shot her nine times, pausing to reload. Two of his sons witnessed the slayings of their mother and grandfather.

ONE RELATIVE'S PERSPECTIVE: Boyd's brother-in-law, Craig Curry of Stoneville, says he believes Boyd deserves to die for his crimes. Curry was in the house that night, witnessed the slayings and was threatened and shot at by Boyd.

PLEA FOR MERCY: Boyd's lawyer, Thomas Maher of Chapel Hill, argued the execution should not happen because the crime was out of character for Boyd, whom he described as a soft-spoken Vietnam veteran with no previous criminal record. At the time of the killings, Maher said, Boyd had been drinking and was struggling with the failure of his marriage. Maher had filed last-minute appeals based on claims of juror misconduct and bias.

STATE'S RESPONSE: State prosecutors argued that Boyd's execution should not be delayed because of the unproven allegations, some of which Boyd's lawyers learned about years ago but didn't raise until the last minute.

NEXT EXECUTION: Perrie Dyon Simpson, 43, is scheduled to be executed Jan. 20 at Central Prison for the 1993 murder of the Rev. Jean Ernest Darter in Rockingham County. The night before the killing, Darter had let Simpson and his pregnant girlfriend into his home because they were hungry, court records say. Darter fed them some peaches and cake and gave them $4, records say. The next night, Simpson came back and strangled Darter.

"Boyd’s family says he didn’t deserve to die," by Shelvia Dancy. (Updated: 12/2/2005 10:34:28 AM)

(RALEIGH) -- Kenneth Smith walked into Raleigh's Central Prison on Thursday for one of his last visits with his father, convicted killer Kenneth Lee Boyd.

"It's been real emotional, hard on all of us,” Smith said. “We're just trying to make the best of a bad situation."

While time ran out for Boyd, the family prayed for clemency from Governor Easley.

"I hope the governor has a heart and grants clemency,” Kenneth said. “He doesn't deserve the death penalty."

Twenty-two inmates have been executed since Governor Easley took office five years ago. Easley has only granted clemency twice.

"N. Carolina carries out 1,000th execution," by Andy sullivan. (Fri Dec 2, 2005 2:54 AM ET)

RALEIGH, North Carolina (Reuters) - A double murderer became the 1,000th prisoner executed in the United States since the reinstatement of capital punishment when he was put to death by lethal injection on Friday.

Kenneth Lee Boyd, who was 57, died at 2:15 a.m. (0715 GMT) in the death chamber of Central Prison in North Carolina's state capital, Raleigh, spokeswoman Pamela Walker of the Department of Corrections said. Boyd was strapped to a gurney and injected with a fatal mix of three drugs.

Boyd, a Vietnam war veteran with a history of alcohol abuse, was sentenced to death for the murder in 1988 of his wife and father-in-law committed in front of two of his children.

"I was just going to ask Kathy, my daughter-in-law, to look after my son and my grandchildren. God bless everybody in here," Boyd said in his last words to witnesses, according to an official statement from the corrections department.

Boyd's execution drew world attention because of the milestone it represented since the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the death penalty to be brought back in 1976 after a nine-year unofficial moratorium.

About 100 death-penalty opponents gathered on a sidewalk outside the prison where they held candles and read the names of the other 999 convicts who have been put to death.

Between 16 and 18 of the protesters were detained shortly before midnight and charged with trespassing after stepping onto prison property, police said. Witnesses said many in the group had been on their knees in prayer on a prison driveway.

"This was a peaceful demonstration. They just violated the rules," said State Capitol Police Chief Scott Hunter.

Boyd's last chance of life ran out less than four hours before his appointment with death when Gov. Mike Easley said he saw no compelling reason to grant clemency.

In his final few hours, he ate a last meal of steak, baked potato and salad and met his family for the last time.

"His concern is that who he is will get lost in a bizarre coincidence that he's number 1,000," Boyd's lawyer Thomas Maher told Reuters late on Thursday.

"He said it best: 'I'm a person, not a statistic'."

GARY GILMORE WAS FIRST

The first convict to be executed after the death penalty returned to the United States, Gary Gilmore, died in front a firing squad in Utah on January 17, 1977, after ordering his lawyers to drop all appeals.

A novel about his case, "The Executioner's Song," won writer Norman Mailer a Pulitzer Prize. Gilmore donated his eyes for transplant, inspiring a British punk rock song.

Thirty-eight of the 50 U.S. states and the federal government permit capital punishment and only China, Iran and Vietnam held more executions in 2004 than the United States, according to rights group Amnesty International.

But while the death penalty retains support with a clear majority of Americans, the number of executions has fallen sharply in recent years, and was down to 59 last year.

Duke University law professor Jim Coleman, who has headed American Bar Association efforts to impose a moratorium, said Boyd would not have been sentenced to death if he were tried today because defense lawyers are better and jurors are more reluctant to impose the ultimate punishment.

"If you were starting from scratch, my guess is nobody would think that the death penalty is a great idea," he said.

Singapore, which has the world's highest execution rate relative to population, also carried out a death penalty on Friday. The hanging of Australian drugs trafficker Nguyen Tuong Van went ahead despite repeated Australian government pleas for clemency.

South Carolina was scheduled to execute another American, Shawn Paul Humphries, by lethal injection at 6 p.m. (2300 GMT) on Friday for the killing of a convenience store owner in a robbery.

"North Carolina Man Is 1,000th Executed," by Brenda Goodman. (December 1, 2005)

Just after 2 a.m., a North Carolina man became the 1,000th person to be executed in the U.S. since the Supreme Court upheld states' rights to order the death penalty in 1976. The somber moment drew a sizeable crowd to Central Prison in Raleigh, N.C., to protest capital punishment.

Kenneth Lee Boyd, 57, of Rockingham, N.C., died by lethal injection for the 1988 shootings of his estranged wife, Julie Curry Boyd, who was 36, and her father, Thomas Dillard Curry, 57. Members of both families had asked to be present.

Mr. Boyd's son, Kenneth Smith, 35, who visited his dad every day for the last two weeks, said in an interview on Thursday that he felt the attention paid to the milestone had hurt his father's chances for clemency.

Mr. Smith also said his dad was deeply troubled that he might only be remembered as a grim hash mark in the history books.

"He didn't want to be 999, and he didn't want to be 1001 if you know what I mean," said Mr. Smith. "He wanted to live."

Mr. Boyd's attorney, Thomas Maher, had hoped to win a stay for his client, who he said had an I.Q. of 77. The cutoff for mental retardation, a mitigating factor in some capital cases, is 75. He also hoped the U.S. Supreme Court and North Carolina Governor Mike Easley would consider that before these murders, Mr. Boyd had no history of violent crime, and that he had volunteered to go to war in Vietnam.

Belinda J. Foster, District Attorney for Rockingham, N.C., who prosecuted Mr. Boyd, said she felt confident that the death penalty was warranted in this case.

In March of 1988, Mr. Boyd shot his father-in-law twice with a .35 Magnum before turning the gun on his estranged wife. He shot her eight times. Christopher Boyd, their son, was pinned underneath his mother's body. Paramedics later found the boy hiding under a bed, covered in her blood, Ms. Foster said.

"There are cases that are so horrendous and the evidence so strong it just warrants a death sentence," Ms. Foster said.

Michael Paranzino, President of the pro-death penalty group Throw Away the Key, agreed.

"You'll never stop crimes of passion, but I do believe the death penalty is a general deterrent, and it expresses society's outrage," Mr. Paranzino said.

An October 2005 Gallup poll found that 64 percent of all Americans support capital punishment in murder cases.

Mr. Boyd never denied his guilt, but said he couldn't remember killing anyone and didn't know why he did it.

"We believe this occasion is the perfect time to reconsider the whole issue of execution," said William F. Schulz, executive director of Amnesty International, a group that has sought to end the practice of using executions as a punishment for crime around the world.

"Since 1976, about one in eight prisoners on death row in the U.S. has been exonerated. That should raise serious questions about ending a person's life," Mr. Schulz said.

Others argue that the death penalty should be reconsidered because it is so arbitrarily applied.

The vast majority of those sentenced to death for their crimes are impoverished and live in the South, said Stephen B. Bright, director of the Southern Center for Human Rights and a long time advocate for death row inmates.

"Texas has put 355 people to death in the last 30 years, with just one county in Texas, Harris County, accounting for more executions than the entire states of Georgia or Alabama. Where is the justice in that?" asked Mr. Bright.

As to the provision of justice, Marie Curry, who lost her husband and her daughter when Mr. Boyd shot them 17 years ago, said she was at a loss to provide any answers.

"I really don't know, " she said.

Mrs. Curry raised Mr. Boyd's three sons, Christopher, Jamie, and Daniel, after their father was sent to prison for their mother's murder.

"It's just a sad day. The bible says to forgive anyone that asks you, and I did," she said, "But I can't ever forget."

"Double killer is nation's 1,000th execution; Capital punishment was resumed in 1977. (December 2, 2005)

RALEIGH, North Carolina (AP) -- A convicted murderer was put to death Friday in the nation's 1,000th execution since capital punishment resumed in 1977.

Kenneth Lee Boyd, who was convicted of killing his estranged wife and father-in-law, received a lethal injection and was pronounced dead at 2:15 a.m.

"The execution of Kenneth Boyd has not made this a better or safer world," his attorney, Thomas Maher, said. "If this 1,000th execution is a milestone, it's a milestone we should all be ashamed of."

In his final words, Boyd asked his daughter-in-law to take care of his son and grandchildren and said, "God bless everybody in here."

His execution came after both Gov. Mike Easley and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene.

About 150 protesters gathered at the prison in Raleigh, where prison officials tightened security. Police arrested 16 protesters late Thursday who sat down on the prison's four-lane driveway, officials said.

Boyd, 57, did not deny that he shot and killed Julie Curry Boyd, 36, and her father, 57-year-old Thomas Dillard Curry. Family members said Boyd stalked his estranged wife after they separated following 13 stormy years of marriage and once sent a son to her house with a bullet and a threatening note.

During the 1988 slayings, Boyd's son Christopher was pinned under his mother's body as Boyd unloaded a .357-caliber Magnum into her. The boy pushed his way under a bed to escape the barrage. Another son grabbed the pistol while Boyd tried to reload.

The Supreme Court in 1976 ruled that capital punishment could resume after a 10-year moratorium. The first execution took place the following year, when Gary Gilmore went before a firing squad in Utah.

Boyd became the 1,000th execution.

He told The Associated Press in a prison interview that he wanted no part of the infamous numerical distinction. "I'd hate to be remembered as that," Boyd said Wednesday. "I don't like the idea of being picked as a number."

The 1,001st execution could come Friday night, when South Carolina plans to put Shawn Humphries to death for the 1994 murder of a store clerk.

Lawyers say war trauma was factor

In Boyd's plea for clemency, his attorneys argued his experiences in Vietnam -- where as a bulldozer operator he was shot at by snipers daily -- contributed to his crimes.

As the execution drew near, Boyd was visited by a son from a previous marriage, who was not present during the slayings.

"He made one mistake, and now it's costing him his life," said Kenneth Smith, 35, who visited with his own wife and two children. "A lot of people get a second chance. I think he deserves a second chance."

Smith's wife witnessed the execution, along with Thomas Curry's niece and her husband.

Maher, a small group of law enforcement officials and journalists also watched through the thick, twin glass panes between the viewing room and the stark death chamber.

"Execution day draws near," by J. Brian Ewing. (Tuesday, November 29, 2005)

As the execution day draws closer, Boyd will be removed from death row, where 171 inmates currently reside, and taken to the "death watch" area on the prison's second floor.

A thick metal door seals off the room. The door looks exactly like most at the prison except its large windows are covered with brown paper concealing the room on the other side. The room is about 500 square feet with three cells, a steel table and a shower.

Two guards remain in the room with the inmate at all times while another guard monitors from outside. Branker said prisoners spend little time here however.

In the 24 hours leading up to the execution, prisoners spend most their time with their lawyers and family and friends in a visiting room, Branker said. Visiting hours on the eve of the execution are from 10 a.m. until 11 p.m. A wall separates the inmate and his family during the visits. Branker said contact visits are rare and at the warden's discretion.

After visiting hours are over, the prisoner's spiritual advisor sits with him as the final hour draws near.

Branker said at 1 a.m. the warden asks the prisoner to strip to his shorts and socks. He is then led from the death watch area to a small staging room located only a few feet away and outside the death chamber. The inmate is secured to a gurney by the ankles and wrists. Two saline intravenous lines are started, one in each arm and the inmate is covered with a sheet.

The inmate is then given the opportunity to make a final statement, which the warden takes down and makes public after the execution. The inmate is then given a chance to pray with the chaplain.

Forty minutes later, the witnesses for the execution are led into the observation gallery. Only 16 people can fit in the 115 square-foot room. Two rows of four blue plastic chairs sit close to the large observation window.

Witnesses to executions include officials selected by the district attorney and sheriff of the county where the inmate was convicted and as many as four citizens. The inmate may also select as many as five people to witness the execution. A 1997 amendment also gave the right for two members of the victim's family to attend the execution as well.

Pamela Walker, a spokesperson for the Department of Corrections, said by this time dozens of people have lined the street outside the prison to protest and hold a vigil for the inmate. She said earlier in the day the crowd might reach as many as 70 people but as the night draws on the numbers thin.

At 1:50 a.m., the warden calls Corrections Secretary Theodis Beck to test the phone line should any last-minute reprieve come.

Five minutes later, Branker said, the warden calls Beck back for permission to proceed with the staging. The inmate is then wheeled into the death chamber and a curtain is drawn behind him to protect the identity of the personnel who will administer the fatal doses.

During this time, the inmate and the witnesses can see one another. Captain Marshall Hudson has witnessed several executions during his career at Central Prison and he said inmates sometimes mouth things to the gallery.

"Typically he says 'I'm sorry, I love you, I'm going home,'" Hudson said.

A third and final call is made at 2 a.m. giving the warden permission to execute the inmate. At that time, two syringes are depressed slowly. One syringe contains no less than 3,000 milligrams of sodium pentothal, a short acting barbiturate that puts the inmate to sleep. The second syringe contains saline to flush the IV line clean.

A third syringe is then injected. This syringe contains no less than 40 milligrams of Pavulon, a paralyzing agent.

Then a fourth syringe injects no less than 160 millequivalents of potassium chloride. At this dosage the drug interrupts nerve impulses to the heart, causing it to stop beating.

A final injection of saline is administered to flush the IV.

After the inmate's heart monitor flat lines for five minutes, he is pronounced dead. A curtain is drawn over the observation window and Branker said the warden informs the witnesses.

The body is then released to the medical examiner.

Boyd told the Eden Daily News he is prepared for his execution. He said he has regretted what he did to his wife and father-in-law everyday since committing the murders. He said he hopes his death helps those he hurt find some relief.

"Protesters march," by J. Brian Ewing. (Friday, December 2, 2005)

A light rain fell Thursday night outside of Raleigh's Central Prison as protesters began their vigil for death row inmate Kenneth Lee Boyd.

Boyd, 57, was scheduled to be the 1,000th inmate executed in the United States since capital punishment was reinstated in 1976.

Boyd spent the day with his son Kenneth Smith, 32, his daughter-in-law Cheryl Boyd and his three grandchildren as well as two family friends.

Boyd was convicted in a 1994 retrial for murdering his wife Julie Curry Boyd and her father Thomas Curry at their Stoneville home.

Boyd shot Curry twice and Julie Boyd eight times. He committed the murders in front of two of his children including Chris Boyd, whose wife Cheryl visited with Kenneth Boyd all day Thursday.

Cheryl Boyd said her father-in-law seemed happy and content.

"He talked about his sons and hopes that they find it in their hearts to forgive him," Cheryl Boyd said.

Cheryl Boyd said her husband had not spoken to her about the execution.

Kenneth Boyd did receive a tearful phone call from his son Daniel Boyd.

A last minute appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was denied early Thursday afternoon. Gov. Mike Easley announced his denial for clemency just before 11 p.m.

As the final hour drew near, Kenneth Smith returned from speaking with his father.

Smith said he and his father reminisced about their times together when he was a boy. Smith is a son from a previous marriage. He said if he regretted one thing it was that he didn't get to spend more time with his father.

Smith said he has long been an opponent of the death penalty. Desmond Carter, a convicted murderer and a childhood friend of Smith's from Rockingham County, was also executed at Central Prison.

"I don't think it's fair. There are so many different standards," he said. "There's so much killing going on in the government. One thousand people, that's a lot of people that's been killed."

Smith said he brought his two children to see their grandfather one last time because, "I wanted them to know my dad's a good person."

Boyd's case gained international notoriety when Virginia Gov. Mark Warner, an outspoken opponent to the death penalty, pardoned killer Robin Lovitt earlier this week. Lovitt, whose execution was originally scheduled for Tuesday, would have been the 1,000th. Boyd has said told his family that he does not want to be remembered as a number.

More than 100 protestors outside Central Prison were telling reporters that 1,000 executions were 1,000 too many.

"It's a sad statement of us as a society that violence begets violence," Pastor Mark Reamer of Saint Francis of Assisi said.

Reamer led a candlelight vigil march to the prison Thursday night. He said the Catholic Church has long opposed capital punishment and he said he prayed for an end to it.

Also among the protestors was a small group from Wakefield High School. They were there representing civil rights group Amnesty International. David Zoppo, 17, coordinated the group and said he finds it ironic that the punishment for killing is killing.

"You can't use killing as a punishment. You're doing what he has done." Zoppo said. He said most students his age aren't aware about social concerns like the death penalty but he wanted to inform more.

As the rain let up just before 11 p.m., officials in the prison began preparing for the execution. Earlier that day Kenneth Lee Boyd had a New York strip steak, medium well, and a baked potato for supper. Officials said he was pleased with his last meal.

A man sentenced to die for killing his wife and father-in-law is scheduled to be executed Dec. 2. Kenneth Lee Boyd, now 57, was was sentenced to death July 14, 1994, in Rockingham County Superior Court for the March 1988 shooting deaths of his estranged wife Julie Curry Boyd and her father Thomas Dillard Curry.

The shootings were committed in the presence of his own children, then ages 13, 12 and 10, as well as other witnesses, all of whom testified against Boyd at trial. According to family members, Julie had endured an extremely stormy marriage for 13 years before finally leaving Boyd and moving herself and her children in with her father. Boyd repeated stalked Julie, once handing one of their sons a bullet and a note to give his mother that said the bullet was intended for her.

On March 4, 1988 Boyd drove around with his boys, telling them he was going to go and kill everyone at his father-in-law's home. When they arrived, he entered the home and shot and killed both his wife and her father with a .357 Magnum pistol. One of Julie's sons was pinned under his mother's body as Boyd continued to fired at her. The child scrambled out from beneath his mom's body and wriggled under a nearby bed to escape the hail of bullets. When Boyd tried to reload the pistol, another son tried to grab it. Boyd went to the car, reloaded his gun, came back into the house and called 911, telling the emergency operator, "I've shot my wife and her father - come on and get me." Then more gunshots can be heard on the 911 recording.

Law enforcement officers arrived and as they approached Boyd came out of the nearby woods with his hands up and surrendered to the officers. Later, after being advised of his rights, Boyd gave a lengthy confession in which he described the fatal shootings: "I walked to the back door and opened it. It was unlocked. As I walked in, I saw a silhouette that I believe was Dillard. It was just like I was in Vietnam. I pulled the gun out and started shooting. I think I shot Dillard one time and he fell. Then I walked past him and into the kitchen and living room area. The whole time I was pointing and shooting. Then I saw another silhouette that I believe was Julie come out of the bedroom. I shot again, probably several times. Then I reloaded my gun. I dropped the empty shell casings onto the floor. As I reloaded, I heard someone groan, Julie I guess. I turned and aimed, shooting again. My only thoughts were to shoot my way out of the house. I kept pointing and shooting at anything that moved. I went back out the same door that I came in, and I saw a big guy pointing a gun at me. I think this was Craig Curry, Julie's brother. I shot at him three or four times as I was running towards the woods."

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Do Not Execute Kenneth Lee Boyd!

NORTH CAROLINA - Kenneth Lee Boyd - December 2, 2005

Kenneth Lee Boyd, a white man, faces execution in North Carolina for the shooting deaths of his wife, Julie Curry Boyd, and her father, Thomas Dillard Curry, on March 4, 1988 in Rockingham County.

Boyd dropped out of school in the ninth grade. He later volunteered to serve in the army and went to Vietnam. He suffers from a history of alcohol abuse. His first marriage ended in divorce and his marriage to Julie Boyd involved a history of arguments, separations, and reconciliations. At the time of the murders the two were separated. Boyd also suffered from an intestinal illness that had resulted in the removal of both his stomach and his gall bladder on two separate occasions.

At Boyd’s trial, expert witnesses testified as to Boyd’s psychiatric state of mind. Dr. Patricio Lara testified that Boyd suffered from adjustment disorder with psychotic emotional features, alcohol abuse, and personality disorder with predominate compulsive dependant features. Dr. John Warren testified that Boyd suffered from chronic depression, alcohol abuse disorder, dependant personality disorder, and a reading disability. Dr. Warren also stated that Boyd did not act with a “cool state of mind” at the time of the murders. After an explanation by the court of the legal meaning of a “cool state of mind,” Warren conceded that the medical and legal uses of the terms differed. However Warren stated that Boyd did not act with a “cool state of mind” in the medical sense. Although the witness clarified his testimony, that part of his testimony was ruled inadmissible.

Additionally, Boyd’s trial judge allowed a conversation on mitigating circumstances between the attorneys and the judge to take place outside of Boyd’s presence. According to the law the defendant has a right which can not be waived to be present at all parts of his capital trial. In this instance the appellate court ruled that Boyd’s absence was “harmless” because his lawyer was present.

Unfortunately there is also question as to whether Boyd received effective assistance of counsel. During closing arguments, trial counsel responded to the prosecutor’s closing argument that the jury should look at the ten minutes of the crime and return a death sentence. The defendant’s counsel responded by arguing that the jury “take the ten minutes to find the aggravating circumstance.” He continued by telling the jury to rule on all of the information in the case, not just that ten minutes. Unfortunately such a statement by the trial counsel both concedes that such an aggravating circumstance exists and concedes the guilt of the defendant. The statement concedes guilt because the aggravating circumstance in this case was whether each murder was committed during the commission of another murder. The appellate court ruled that this did not warrant a mistrial because the defendant did not voice his problem with his trial counsel’s statements before the appeal. Of course, a defendant is not likely to object before appeal to the statement of his own counsel.

Boyd has a number of mental and emotional problems. He suffers from an addiction to alcohol and was intoxicated at the time of the crimes. He has been cooperative with authorities and has no prior criminal record.

Please write Gov. Michael Easely requesting that Boyd’s sentence be commuted to life in prison.

People of Faith against the Death Penalty

Updated Nov. 30, 2005

Kenneth Boyd May Be 1,000th U.S. Execution Since 1977.

Barring a court-ordered stay or clemency from NC Gov. Mike Easley, Kenneth Lee Boyd will be the 1,000th person executed in the United States since the resumption of executions in the United States in 1977.

Abolitionists and concerned Americans from around the country are flying and busing to North Carolina to protest Friday morning's scheduled execution of Boyd. Protests are planned in more than 12 cities around the state and in cities around the country.

Please join us in prayer and reflection on this sad milestone. Please remember to call Gov. Easley's office and consider attending a prayer service at one of many locations in the state. The governor's telephone numbers are 1-800-662-7952 (in North Carolina only) and (919) 733-5811. Sign up for our e-mail alerts and listservs for more developments on this story (see links at upper right.)

"How embarassing for North Carolina and how tragic if this execution is carried out," said Stephen Dear, executive director of People of Faith Against the Death Penalty. "The world is watching us. As our legislature is about to begin a study of the widely documented flaws in our death penalty system and as polls here continue to show broad public support for suspending executions, to carry out this execution will mark a sad, even pathetic, day in North Carolina history.

"Let us take the hundreds of millions of tax dollars North Carolina spends on the death penalty and invest it in crime prevention and in real, restorative programs aimed at meeting victims' needs," Dear said.

Gov. Easley has granted clemency twice, but has allowed more exections than any North Carolina governor since 1949.

"Gov. Easley has been on the wrong side of history," Dear said. "We pray he will have a transformation in his heart and his conscience."

Governments and faith and humanitarian groups in more than 300 cities around the world will be organizing events calling for the abolition of the death penalty on Nov. 30. The "Cities for Life - Cities Against the Death Penalty" day celebrates the anniversary of the first abolition of capital punishment by law in a European state, the Great Duchy of Tuscany in 1786. (For information visit http://www.worldcoalition.org/bcoalactu01.html)

One juror from the Boyd trial has since said that she was under the mistaken impression that the death penalty was automatic once the jurors found that the crime was premeditated. She never believed that Boyd deserved to die. In addition to her misunderstanding of the law, she felt pressured by some of the other jurors into going along with a death sentence, a decision she deeply regrets.

Additional information can be found at www.1000execution.org.

The world will be watching if North Carolina kills Kenneth Boyd early Friday morning. Let us pray, and let us act, so that it will not happen here.

1000 Exexutions - Enough Already . . .Abolish the Death Penalty

State v. Boyd, 332 N.C. 101, 418 S.E.2d 471 (N.C. 1992) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted of murder in Superior Court, Rockingham County, Sam Currin, J., and he appealed. The Supreme Court, Exum, C.J., held that: (1) court's private conversation with juror warranted new trial, and (2) defendant was entitled to state-paid mental health expert if defendant did not have sufficient funds to pay for one.

Remanded for new trial.

EXUM, Chief Justice.

There are two assignments of error which merit discussion. The first relates to the trial court's excusing a juror from service at defendant's trial during the jury **472 selection process and deferring her for service at a later session after a private, unrecorded bench conference with the juror. For this error, defendant is entitled to a new trial. The second assignment brings forward the trial court's denial of defendant's pretrial motion for a state-paid mental health expert to assist defendant in the preparation of his defense. Since the denial of this motion on the grounds given by the trial court was error, we discuss this assignment for the guidance of the trial court on retrial.

The evidence offered at trial may be briefly summarized inasmuch as it has little bearing on the assignments of error which we address. Essentially, the State's evidence tended to show: On 4 March 1988 defendant entered the home of his estranged wife's father, where his wife and their children were then living, and shot and killed both his wife, Julie Boyd, and her father, Dillard Curry, with a .357 Magnum pistol. The shooting was committed in the presence of the children--Chris, aged thirteen; Jamie, aged twelve; and Daniel, aged thirteen--and other witnesses, all of whom testified for the State. Law enforcement officers were called to the scene. As they approached, defendant came out of the woods with his hands up and surrendered to the officers. Defendant showed *103 the officers where he had thrown the murder weapon into some adjacent woods. Later, after being advised of his rights, defendant made a lengthy inculpatory statement in which he described the fatal shootings, saying, "It was just like I was in Vietnam."

Defendant's evidence at trial tended to show: Defendant voluntarily served in the United States Army and volunteered for duty in Vietnam, where he was assigned to a combat engineering unit. He habitually drank alcoholic beverages to excess while in the military and since his discharge. His first marriage ended in divorce. His second marriage in 1973 to Julie Boyd was marked by frequent arguments, some violence, several separations and reconciliations. Defendant suffered intestinal illnesses which resulted in the removal of much of his stomach on one occasion and his gallbladder on another. He had sought mental health counseling. He continued to drink alcoholic beverages to excess and had drunk a number of beers on the day of the fatal shooting. His recollection of the time before and during the shootings was incomplete, but he remembered being at the Curry home, his gun going off, and seeing blood. He denied going there with the intent to kill either Julie Boyd or Dillard Curry.

Dr. Patrico Lara, a psychiatrist employed at Dorothea Dix Hospital, examined defendant periodically over a two-week period beginning 11 March 1988. Dr. Lara, testifying for defendant, thought defendant did not suffer from brain damage nor was his understanding of his situation "confused or incoherent." Dr. Lara diagnosed defendant as suffering from an "adjustment" and "personality" disorder with various features which he described for the jury.

Following jury verdicts of guilty of two counts of first-degree murder, a capital sentencing proceeding was convened. The State offered no additional evidence but relied on evidence offered during the guilt proceeding. Defendant offered several family members and others as witnesses who gave favorable accounts of his early childhood, his military career, his relationship with his children, and his employment as a truck driver.

The trial court submitted and the jury found one aggravating circumstance in each murder case: The murder was part of a course of conduct that included the commission by defendant of other crimes of violence against other persons. See N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(e)(11) (1988). The jury unanimously found four of ten mitigating circumstances submitted but failed to find unanimously *104 six mitigating circumstances, including the mitigating circumstances that (1) defendant was under the influence of a mental or emotional disturbance and (2) his capacity to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was impaired when he committed the murders. See N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(f)(2), (6) (1988).

The State concedes that the testimony of Dr. Lara was sufficient to support both the mental or emotional disturbance and the impaired capacity mitigating circumstances. The State further concedes that the jury instructions on mitigating circumstances violated the Federal Constitution as interpreted in McKoy v. North Carolina, 494 U.S. 433, 110 S.Ct. 1227, 108 L.Ed.2d 369 (1990); see also State v. McKoy, 327 N.C. 31, 394 S.E.2d 426 (1990). The State agrees that because of this error defendant is entitled to a new sentencing hearing.

We conclude that defendant is entitled to a new trial because the trial court excused a juror during the jury selection process in defendant's trial after a private, unrecorded conference with the juror at the bench. The transcript of the trial reveals that during the second day of jury selection additional jurors were called by the clerk to come forward for questioning. The transcript reveals only the following regarding the incident in question:

CLERK: William Harris, Charlotte Jackson. (Ms. Jackson brought a letter up and handed it to the Bailiff, who then handed it to the judge. The judge then talked to the lady at the Bench.)

COURT: Ma'am Clerk, at this time I am going to defer that particular juror's service until one of the terms during the summer months. And if you will call another juror.

There is nothing in the trial transcript nor in the record on appeal which reveals the substance of the conversation between the trial court and prospective juror Jackson.

Our cases have long made it clear that it is error for trial judges to conduct private conversations with jurors. We said in State v. Tate, 294 N.C. 189, 198, 239 S.E.2d 821, 827 (1978):

[T]he trial court's private conversations with jurors were ill-advised. The practice is disapproved. At least, the questions and the court's response should be made in the presence of counsel.

Tate being a noncapital prosecution, [FN1] we concluded that defendant, by not objecting to the judge's action, waived his right to complain of it on appeal. In capital prosecutions, however, we have long recognized that a defendant may not waive his right to be present at every stage of his trial. State v. Moore, 275 N.C. 198, 166 S.E.2d 652 (1969); State v. Jenkins, 84 N.C. 813 (1881). Thus we have held that private conversations between the presiding judge and jurors during a capital trial, even in the absence of objection by defendant, violated defendant's right of confrontation guaranteed under Article I, Section 23, of the North Carolina Constitution and constituted reversible error unless the State could demonstrate its harmlessness beyond a reasonable doubt. State v. Payne, 320 N.C. 138, 357 S.E.2d 612 (1987). Since there was no record of what transpired during the conversations in Payne, we concluded the State could not demonstrate the harmlessness of the error.

FN1. The crime was committed on 25 December 1976, before the enactment of our present death penalty statute in 1977 and after the immediately preceding death penalty statute had been declared unconstitutional in Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 96 S.Ct. 2978, 49 L.Ed.2d 944 (1976).

In State v. Smith, 326 N.C. 792, 392 S.E.2d 362 (1990), a capital prosecution, the trial court spoke privately with prospective jurors during the jury selection process, after which the jurors were excused from having to serve. Neither the record on appeal nor the trial transcript reflected the substance of the bench conferences, except to note the trial court's conclusion that it was within its discretion to excuse each juror. This Court, cognizant of the principles announced in Tate and Payne, concluded that the process of selecting and impaneling a jury is a stage of the trial to which the defendant's right of confrontation applies and the trial court's excusal of jurors after the private conversations violated that right. We also concluded the private conversations violated the trial court's statutory duty in a capital case to make an accurate record of the jury selection process. N.C.G.S. § 15A-1241(a) (1988). Recognizing the error was subject to harmless error analysis with the burden being on the State to demonstrate its harmlessness **474 beyond a reasonable doubt, we concluded the State could not meet that burden because "[n]o record of the trial court's private discussions with the prospective jurors exists to reveal the substance of those discussions." Smith, 326 N.C. at 794, 392 S.E.2d at 363-64.

Smith 's rationale and holding have been followed in State v. Johnston and Johnson, 331 N.C. 680, 417 S.E.2d 228 (1992); State v. Cole, 331 N.C. 272, 415 S.E.2d 716 (1992); and State v. McCarver, 329 N.C. 259, 404 S.E.2d 821 (1991). Where, however, the transcript reveals the substance of the conversations, State v. Payne, 328 N.C. 377, 402 S.E.2d 582 (1991), or the substance is adequately reconstructed by the trial judge at trial, State v. Hudson, 331 N.C. 122, 415 S.E.2d 732 (1992); State v. Ali, 329 N.C. 394, 407 S.E.2d 183 (1991), we have been able to conclude that the error was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

[3] Here, the substance of the conversation between the trial judge and the excused juror is not revealed by the transcript nor did the trial judge reconstruct it at trial. The State, therefore, cannot demonstrate the harmlessness of the error beyond a reasonable doubt; and defendant must be given a new trial.

That the juror was deferred for service at a future date rather than excused altogether does not call for a different result. State v. Cole, 331 N.C. 272, 415 S.E.2d 716 (1992). Whether deferred or excused altogether, the juror was rendered unavailable for defendant's trial.

The State on 2 May 1991, four days before oral argument, moved the Court to allow an amendment to the record on appeal. The desired amendment consisted of affidavits of the deputy clerk of court in Rockingham County and the presiding trial judge, signed, respectively, in April and May 1991, and certain juror records maintained by the clerk. These materials would tend to show that prospective juror Jackson was a substitute teacher then teaching at a public school. The trial judge excused her from juror duty for defendant's trial and deferred her until a later time because the trial judge concluded her service at that time would create a hardship on the school. This conclusion was based on a letter from Ms. Jackson's principal.

Defendant responded to this motion on 14 May 1991 and contends the motion should be denied inasmuch as it "seeks to reconstruct a record of events leading to Ms. Jackson's deferral long after the occurrence of the underlying event."

The State's motion to amend the record is denied. In State v. McCarver, 329 N.C. 259, 404 S.E.2d 821 (1991), we allowed a new trial for defendant because the trial judge excused jurors *107 following unrecorded bench conferences. In that case the State moved to amend the record to add an affidavit of the trial judge, accompanied by his handwritten trial notes, which explained his reasons for excusing the jurors. We denied the motion, saying, "The court reporter did not record the bench conferences, as required by N.C.G.S. § 15A-1241. We will not substitute for this statutory requirement an affidavit made approximately three years after the event. The affidavit was not a part of the record made at trial." Id. at 261, 404 S.E.2d at 822. McCarver controls and requires that the State's motion to amend the record here be likewise denied.

This brings us to the second assignment of error which we discuss only for the guidance of the trial court on retrial. Defendant before trial moved pursuant to N.C.G.S. § 7A-450(a) for state funding for a mental health expert. Judge Beaty, who heard the motion before trial, acknowledged defendant's affidavit indicating that he had no funds. He nonetheless noted that defendant had released court-appointed counsel and had retained different, privately employed counsel. When he questioned defendant about this, defendant stated that someone else was paying for his counsel and that he had no assets except a 1987 tax refund. Judge Beaty offered defendant the option of accepting different, court-appointed counsel as a condition of receiving funds for an expert witness. When defendant rejected this option, Judge Beaty denied his motion, concluding "the **475 defendant, though indigent, has retained private counsel and is therefore not entitled to State funds for the presentation of his case or his defense."

At trial defendant renewed his motion for a state-paid mental health expert and tendered to the trial judge various mental health records of defendant. The trial judge reaffirmed Judge Beaty's earlier conclusion that because defendant was not represented by court-appointed counsel he was not indigent and not entitled to state assistance pursuant to N.C.G.S. § 7A-450(a). The trial judge denied the motion on this ground.

We address here only the question whether defendant's motion for a state-paid mental health expert should have been denied, as it was, because defendant, although financially unable to employ the expert, was not represented by court-appointed counsel. We conclude, for reasons given below, that the motion should not have been denied on this ground. We express no opinion on whether *108 defendant's motion should have been denied on the ground that he made an insufficient evidentiary showing. [FN2] Neither do we express an opinion on whether Dr. Lara's availability and participation in the trial on defendant's behalf justified denying defendant's motion or rendered the denial harmless. The evidentiary showing at defendant's new trial and in support of this motion will ultimately govern these questions.

FN2. For cases discussing the sufficiency of the factual showing which a defendant must make, see, e.g., Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985); State v. Parks, 331 N.C. 649, 417 S.E.2d 467 (1992); State v. Moore, 321 N.C. 327, 364 S.E.2d 648 (1988); State v. Gambrell, 318 N.C. 249, 347 S.E.2d 390 (1986). See also State v. Phipps, 331 N.C. 427, 418 S.E.2d 178 (1992), on the issue of defendant's entitlement to an ex parte hearing.

Under some circumstances an indigent defendant in a criminal case has a right to be furnished the assistance of a mental health expert. This right is guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985); State v. Gambrell, 318 N.C. 249, 347 S.E.2d 390 (1986), and by statute, State v. Moore, 321 N.C. 327, 364 S.E.2d 648 (1988). An indigent person is defined as one "who is financially unable to secure legal representation and to provide all other necessary expenses of representation." N.C.G.S. § 7A-450(a) (1989). "Whenever a person ... is determined to be an indigent person entitled to counsel, it is the responsibility of the State to provide him with counsel and the other necessary expenses of representation." N.C.G.S. § 7A-450(b) (1989). "The question of indigency may be determined or redetermined by the court at any stage of the action or proceeding at which an indigent is entitled to representation." N.C.G.S. § 7A-450(c) (1989). See also N.C.G.S. § 7A-450(d) (1989). A defendant determined to be partially indigent must pay as he can the expenses of his defense, and the state is required to pay only the remaining balance. N.C.G.S. § 7A-455(a) (1989).

In State v. Hoffman, 281 N.C. 727, 738, 190 S.E.2d 842, 850 (1972), this Court read these statutes as manifesting a legislative intent "that every defendant in a criminal case, to the extent of his ability to do so, shall pay the cost of his defense." In Hoffman, the defendant was determined not to have been indigent at the time of his arrest and thus not entitled to court-appointed counsel at that time. The Court said, however, that the defendant's "ability to pay the costs of subsequent proceedings ... was a matter to be determined when that question arose." Id. at 738, 190 S.E.2d at 850.

We stress, as we did in Hoffman, that the purpose of these statutes is to require defendants to contribute whatever they can to the cost of their representation. But whenever a defendant's personal resources are depleted and he can demonstrate indigency, he is eligible for state funding of the remaining necessary expenses of representation.

That defendant had sufficient resources to hire counsel does not in itself foreclose defendant's access to state funds for other necessary expenses of representation--including expert witnesses--if, in fact, defendant does not have sufficient funds to defray these expenses when the need for them arises.

We vacate the verdicts and judgments entered against defendant and remand this case to the Superior Court, Rockingham County, for a NEW TRIAL.

State v. Boyd

State v. Boyd, 343 N.C. 699, 473 S.E.2d 327 (N.C. 1996) (Retrial Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted before the Superior Court, Rockingham County, Greeson, J., of the first-degree murders of his wife and her father, and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed as of right. The Supreme Court, Mitchell, C.J., held that: (1) trial court did not err in prohibiting expert in forensic psychology from testifying that defendant was not acting with a "cool state of mind" during commission of murders; (2) statement of witness that he believed that defendant was "going to kill everybody" fell within realm of permissible lay testimony, as an instantaneous conclusion as to defendant's condition and state of mind at time of murders; (3) court did not err in refusing to instruct jury on voluntary intoxication; (4) court correctly refused to instruct on defense of unconsciousness; (5) court correctly denied defendant's request for a peremptory instruction as to mitigating circumstance that defendant was under the influence of mental or emotional disturbance; (6) error in conducting conference in chambers to discuss defendant's proposed mitigating circumstances, without defendant present, was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt; and (7) death sentences were not excessive or disproportionate to penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both crime and defendant.

No error.

MITCHELL, Chief Justice.

In June 1994, defendant was again tried capitally and convicted of the first-degree murders of Julie Boyd and Dillard Curry. The jury recommended that defendant be sentenced to death for each murder and the **331 trial court sentenced accordingly. We conclude that defendant received a fair trial free of prejudicial error and that the sentences of death are not disproportionate.

The State's evidence tended to show inter alia that on 4 March 1988 defendant entered the home of his estranged wife's father, where *708 his wife and children were then living, and shot and killed both his wife and her father with a .357 Magnum pistol. The shootings were committed in the presence of defendant's children--Chris, age thirteen; Jamie, age twelve; and Daniel, age ten--and other witnesses, all of whom testified for the State. Immediately after the shootings, law enforcement officers were called to the scene. As they approached, defendant came out of some nearby woods with his hands up and surrendered to the officers.

Later, after being advised of his rights, defendant gave a lengthy inculpatory statement in which he described the fatal shootings:

I walked to the back door [of Dillard Curry's house] and opened it. It was unlocked. As I walked in, I saw a silhouette that I believe was Dillard. It was just like I was in Vietnam. I pulled the gun out and started shooting. I think I shot Dillard one time and he fell. Then I walked past him and into the kitchen and living room area. The whole time I was pointing and shooting. Then I saw another silhouette that I believe was Julie come out of the bedroom. I shot again, probably several times. Then I reloaded my gun. I dropped the empty shell casings onto the floor. As I reloaded, I heard someone groan, Julie I guess. I turned and aimed, shooting again. My only thoughts were to shoot my way out of the house. I kept pointing and shooting at anything that moved. I went back out the same door that I came in, and I saw a big guy pointing a gun at me. I think this was Craig Curry, Julie's brother. I shot at him three or four times as I was running towards the woods.

Dr. Patricio Lara and Dr. John Warren both testified for defendant as experts in forensic psychology. Dr. Lara testified that at the time of the offenses, defendant suffered from an adjustment disorder with psychotic emotional features, alcohol abuse, and a personality disorder with predominate compulsive dependent features. Further, Dr. Lara opined that defendant's emotional condition was impaired and that defendant suffered from some level of alcohol intoxication at the time of the offenses. Likewise, Dr. Warren opined that at the time of the offenses defendant suffered from chronic depression, alcohol abuse disorder, dependent personality disorder, and a reading disability.

In his first assignment of error, defendant argues that the trial court erred in prohibiting Dr. Warren, who testified as an expert in forensic psychology, from testifying that defendant was not acting with a "cool state of mind" during the commission of the murders. During a voir dire on the admissibility of Dr. Warren's testimony, the following exchange occurred:

Q: Dr. Warren, based on your experience and your review of the records that you described concerning [defendant], do you have an opinion as to whether at the time of the events that Mr. Boyd is charged with, he was acting in a cool state of mind?

* * *

The (e)(11) aggravating circumstance itself does not violate due process by reason of unconstitutional vagueness. State v. Williams, 305 N.C. 656, 685, 292 S.E.2d 243, 261, cert. denied, 459 U.S. 1056, 103 S.Ct. 474, 74 L.Ed.2d 622 (1982). Further, we conclude that the evidence in the present case was sufficient to support its submission to the jury.

The State presented substantial evidence tending to show that after defendant fatally shot Dillard Curry, he fired his weapon at Julie *720 Boyd, intending to kill her. The jury, by returning guilty verdicts of first-degree murder for each killing, found beyond a reasonable doubt that defendant had committed the two murders. We have previously held under similar circumstances that the submission of one killing as an aggravating circumstance for another murder under the (e)(11) aggravating circumstance is correct and does not violate due process of law or double jeopardy. State v. Pinch, 306 N.C. 1, 30-31, 292 S.E.2d 203, 225, cert. denied, 459 U.S. 1056, 103 S.Ct. 474, 74 L.Ed.2d 622 (1982), overruled on other grounds by State v. Robinson, 336 N.C. 78, 443 S.E.2d 306 (1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1089, 115 S.Ct. 750, 130 L.Ed.2d 650 (1995), and by State v. Benson, 323 N.C. 318, 372 S.E.2d 517 (1988). Thus, the trial court correctly allowed the jury to consider the murder of Dillard Curry as the crime of violence to support the (e)(11) aggravating circumstance in sentencing defendant for the murder of Julie Boyd. Likewise, the trial court was correct to allow the jury to consider the murder of Julie Boyd as the crime of violence that supported the (e)(11) aggravator in sentencing defendant for the murder of Dillard Curry. In summary, therefore, the trial court properly submitted the aggravating circumstance that each of the murders for which defendant stood convicted was part of a course of conduct in which he engaged and which included the commission of other crimes of violence against another person. Id.; see also State v. Chapman, 342 N.C. 330, 345, 464 S.E.2d 661, 669-70 (1995); State v. Cummings, 332 N.C. 487, 507-12, 422 S.E.2d 692, 703-06 (1992); State v. Brown, 306 N.C. 151, 183, 293 S.E.2d 569, 589, cert. denied, 459 U.S. 1080, 103 S.Ct. 503, 74 L.Ed.2d 642 (1982).

[20] Defendant argues, however, that the trial court did not rely solely on the separate killings for which defendant was found guilty as the other crime of violence. He contends that the trial court improperly instructed the jury that it also could consider an alleged and uncharged assault on Craig Curry as that other crime. Defendant argues that relying on this alleged assault was error in that a prerequisite to the submission of the course of conduct circumstance is that defendant be charged with the other crime of violence. We disagree.

N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(e)(11) does not require that defendant be charged or convicted of the "other crimes of violence" before that aggravating circumstance may be submitted. Unlike other aggravating circumstances that require a conviction, the course of conduct aggravating circumstance is supported not by convictions, but crimes. Compare N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(e)(11) with N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(e)(2) (1995) ("defendant had been previously convicted of *721 another capital felony") and N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(e)(3) ("defendant had been previously convicted of a felony involving the use or threat of violence"). Further, in several decisions, this Court has found that the course of conduct aggravating circumstance was properly submitted when the "other crimes of violence" consisted of evidence of uncharged crimes. State v. Price, 326 N.C. 56, 80-83, 388 S.E.2d 84, 98-99 (course of conduct supported by uncharged arson), sentence vacated on other grounds, 498 U.S. 802, 111 S.Ct. 29, 112 L.Ed.2d 7 (1990); State v. Vereen, 312 N.C. 499, 324 S.E.2d 250 (course of conduct supported by uncharged assault with a deadly weapon inflicting serious bodily injury), cert. denied, 471 U.S. 1094, 105 S.Ct. 2170, 85 L.Ed.2d 526 (1985). As our decisions have instructed, the import of the (e)(11) aggravating circumstance is not that defendant has been charged or convicted of such crimes, but that such crimes connect with the capital murder, whether temporally, by modus operandi or motivation, or by some common scheme or pattern. Cummings, 332 N.C. at 510, 422 S.E.2d at 705.

In the case sub judice, the State presented compelling evidence that immediately after fatally shooting both Dillard Curry and Julie Boyd, defendant turned his weapon and attention toward Craig Curry. Curry testified that while defendant reloaded his weapon, defendant yelled to him, "Come on up here, Craig. I am going to kill you too." Further, defendant testified at trial that

I remember that he [Craig Curry] was standing--I can't swear that it was him. The silhouette was facing toward me with his arm out. I don't know if he had a gun or was just pointing, so I came up with the pistol and started shooting at the silhouette holding it and it took off running across the street.

This was substantial evidence that defendant assaulted Craig Curry with a deadly weapon with the intent to kill him. Thus, the trial court did not err by instructing the jury that it could find as an aggravating circumstance that defendant committed the crime of assault with a deadly weapon with the intent to kill as part of the same course of conduct with the killing of the victims. Defendant's assignment of error is without merit and is overruled.

* * *

Having concluded that defendant's trial and separate capital sentencing proceeding were free from prejudicial error, we turn to the duties reserved by N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(d)(2) exclusively for this Court in capital cases. It is our duty in this regard to ascertain (1) whether the record supports the jury's finding of the aggravating circumstance on which the sentence of death was based; (2) whether the death sentence was entered under the influence of passion, prejudice, or other arbitrary consideration; and (3) whether the death sentence is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime and defendant. N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(d)(2). After thoroughly examining the record, transcripts, *724 and briefs in the present case, we conclude that the record fully supports the aggravating circumstance found by the jury. Further, we find no indication that the sentence of death in this case was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary consideration. We must turn then to our final statutory duty of proportionality review.

In the present case, defendant was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder under the theory of malice, premeditation, and deliberation. The jury found as the sole aggravating circumstance that each murder was part of a course of conduct in which defendant engaged and which included the commission by defendant of other crimes of violence against another person or persons, N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(e)(11). One or more jurors found two statutory mitigating circumstances for each murder, that the murder was committed while defendant was under the influence of mental or emotional disturbance, N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(f)(2), and that the capacity of defendant to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law was impaired, N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(f)(6). In addition, one or more jurors found eighteen nonstatutory mitigating circumstances.

In our proportionality review, it is proper to compare the present case with other cases in which this Court has concluded that the death penalty was disproportionate. State v. McCollum, 334 N.C. 208, 240, 433 S.E.2d 144, 162 (1993), cert. denied, 512 U.S. 1254, 114 S.Ct. 2784, 129 L.Ed.2d 895 (1994). We do not find this case substantially similar to any case in which this Court has found the death penalty disproportionate and entered a sentence of life imprisonment. Each of those cases is distinguishable from the present case.

None of the seven cases in which this Court has found the death penalty disproportionate involved a defendant convicted of murdering multiple victims. See **341 State v. Benson, 323 N.C. 318, 372 S.E.2d 517 (1988); State v. Stokes, 319 N.C. 1, 352 S.E.2d 653 (1987); State v. Rogers, 316 N.C. 203, 341 S.E.2d 713 (1986), overruled on other grounds by State v. Vandiver, 321 N.C. 570, 364 S.E.2d 373 (1988); State v. Young, 312 N.C. 669, 325 S.E.2d 181 (1985); State v. Hill, 311 N.C. 465, 319 S.E.2d 163 (1984); State v. Bondurant, 309 N.C. 674, 309 S.E.2d 170 (1983); State v. Jackson, 309 N.C. 26, 305 S.E.2d 703 (1983). Further, we have said that the fact that defendant is a multiple killer is "[a] heavy factor to be weighed against the defendant." State v. Laws, 325 N.C. 81, 123, 381 S.E.2d 609, 634 (1989), sentence *725 vacated on other grounds, 494 U.S. 1022, 110 S.Ct. 1465, 108 L.Ed.2d 603 (1990); see also State v. McLaughlin, 341 N.C. 426, 462 S.E.2d 1 (1995), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 1133, 116 S.Ct. 956, 133 L.Ed.2d 879 (1996); State v. Garner, 340 N.C. 573, 459 S.E.2d 718 (1995), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 1129, 116 S.Ct. 948, 133 L.Ed.2d 872 (1996); State v. Robbins, 319 N.C. 465, 356 S.E.2d 279, cert. denied, 484 U.S. 918, 108 S.Ct. 269, 98 L.Ed.2d 226 (1987). Because the jury in the present case found defendant guilty of two counts of first-degree murder, this case is easily distinguishable from the seven cases in which the death penalty has been found disproportionate by this Court.

It is also proper for this Court to "compare this case with the cases in which we have found the death penalty to be proportionate." McCollum, 334 N.C. at 244, 433 S.E.2d at 164. We have reviewed all of the cases in the pool of similar cases used to fulfill this statutory duty and conclude the present case is more similar to certain cases in which we have found the sentence of death proportionate than to those in which we have found the sentence disproportionate or those in which juries have consistently returned recommendations of life imprisonment. Accordingly, we conclude that the sentences of death recommended by the jury and ordered by the trial court in the present case are not disproportionate.

For the foregoing reasons, we hold that defendant received a fair trial, free of prejudicial error, and that the sentences of death entered in the present case must be and are left undisturbed.

NO ERROR.

Boyd v. Lee, Not Reported in F.Supp.2d, 2003 WL 22757932 (2004) (Habeas)

SHARP, Magistrate J.

THE STATE COURT PROCEEDINGS

Petitioner Boyd was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder at the October 17, 1988 Criminal Session of the Superior Court of Rockingham County, North Carolina. On Petitioner's direct appeal, the Supreme Court of North Carolina set aside the convictions and ordered a new trial due to legal error of the trial judge in conducting unrecorded, private bench conferences with prospective jurors during jury selection.

Petitioner was tried a second time at the June 13, 1994 Rockingham Criminal Session. On July 7, 1994, Petitioner was convicted of two first-degree murders and sentenced to death for each murder. Petitioner's convictions and sentences were affirmed by the Supreme Court of North Carolina on August 20, 1996. See State v. Boyd, 343 N.C. 699 (1996). The Supreme Court of the United States denied Petitioner's request for certiorari review on January 21, 1997. See Boyd v. North Carolina, 519 U.S. 1096 (1997).