Executed September 10, 2013 06:07 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Oklahoma

24th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1344th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

4th murderer executed in Oklahoma in 2013

106th murderer executed in Oklahoma since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(24) |

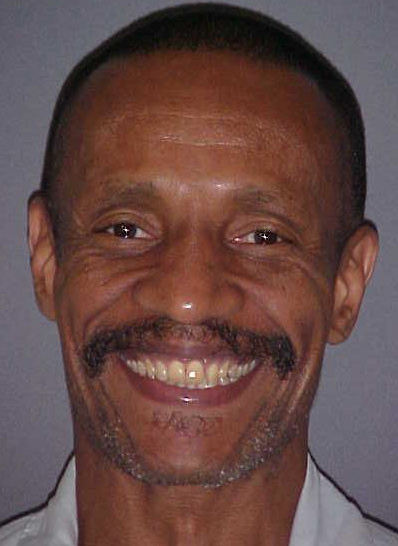

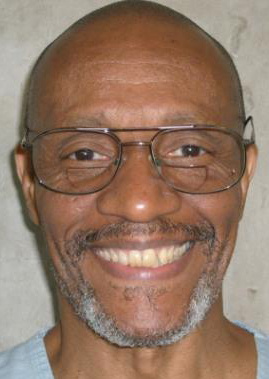

Anthony Rozelle Banks B / M / 26 - 61 |

Sun Kim Travis Asian / F / 24 |

At the time of the DNA identification, Banks was already in prison following his conviction for the 1978 slaying of David Fremin, who was shot and killed during an armed robbery. Banks was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in that case. When his death sentence was reversed on appeal, he pled guilty in exchange for a life sentence.

Citations:

Banks v. State, 701 P.2d 418, (Okla. Crim. App. 1985). (Direct Appeal-Robbery/Murder)

Banks v. State, 43 P.3d 390 (2002 Okla. Crim. App. 2002). (Direct Appeal)

Banks v. Workman, 692 F.3d 1133 (10th Cir. Okla. 2012). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Three apple-filled rolls and two bottles of water.

Final Words:

"I can't express the terrible things I've done. I'm sorry. To know that I took lives hurts me." He said he knew he had also hurt the victims' family members. "This is justified. I've done one good thing in my life and that is to become a Jehovah's Witness. For that, I'm eternally grateful." Banks acknowledged witnesses to his execution, including his attorney, Tom Hird of the Federal Public Defender's Office in Oklahoma City, and an unidentified spiritual adviser. "I'm thankful everybody's here. I appreciate that." Banks singled out Tulsa County Sheriff Stanley Glanz, who also witnessed his execution. "I haven't seen you in years, decades," Banks said with a smile. "God bless you, I love you and I will see you again.

Internet Sources:

Oklahoma Department of Corrections

Inmate: Anthony R Banks

ODOC# 87722

Birth Date: 07/05/1952

Race: Black

Sex: Male

Height: 5 ft. 9 in.

Weight: 160 pounds

Hair: Black

Eyes: Brown

CRF# County Offense Conviction Term Term Code Start End

79-1786 TULS Burglary - Second Degree Afcf 04/11/1980 10Y 0M 0D Incarceration 04/11/1980 04/10/1990

79-2872 TULS Robbery With Firearms Afcf 04/11/1980 10Y 0M 0D Incarceration 04/11/1980 07/31/1989

81-877 TULS Assault & Battery W/Dangerous Weapon 06/19/1981 2Y 0M 0D Incarceration

81-877 TULS Escape From A Penal Institution 06/19/1981 2Y 0M 0D Incarceration

81-877 TULS Assault & Battery W/Dangerous Weapon 06/19/1981 2Y 0M 0D Incarceration

79-3398 TULS Murder First Degree/Felony 11/30/1995 LIFE Life

97-3715 TULS Murder, First Degree In The Commission Of A Felony/Felony 10/28/1999 DEATH 11/22/1999

Death Penalty Information

The current death penalty law was enacted in 1977 by the Oklahoma Legislature. The method to carry out the execution is by lethal injection. The original death penalty law in Oklahoma called for executions to be carried out by electrocution. In 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the death penalty as it was then administered.

Oklahoma has executed a total of 176 men and 3 women between 1915 and 2011 at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Eighty-two were executed by electrocution, one by hanging (a federal prisoner) and 96 by lethal injection. The last execution by electrocution took place in 1966. The first execution by lethal injection in Oklahoma occurred on September 10, 1990, when Charles Troy Coleman, convicted in 1979 of Murder 1st Degree in Muskogee County was executed.

Execution Process

Method of Execution: Lethal Injection

Drugs used:

Sodium Thiopental or Pentobarbital - causes unconsciousness

Vecuronium Bromide - stops respiration

Potassium Chloride - stops heart

Two intravenous lines are inserted, one in each arm. The drugs are injected by hand held syringes simultaneously into the two intravenous lines. The sequence is in the order that the drugs are listed above. Three executioners are utilized, with each one injecting one of the drugs.

"Oklahoma man executed in woman's 1979 slaying." (AP September 10, 2013)

McALESTER, Okla. (AP) — An Oklahoma death row inmate convicted of first-degree murder in the shooting death of a 25-year-old Korean national 34 years ago was executed Tuesday after he apologized for taking the victim's life and said his execution "is justified." Anthony Rozelle Banks, 61, was pronounced dead at 6:07 p.m. after receiving a lethal injection of drugs at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Banks is the fourth Oklahoma death row inmate to be executed this year.

Banks was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death by a Tulsa County jury for the June 6, 1979, killing of Sun "Kim" Travis. Banks was already serving a life prison sentence for his conviction in the April 11, 1978, slaying of a Tulsa convenience store clerk during an armed robbery when he was linked to Travis' death by DNA evidence 18 years after her death.

"I can't express the terrible things I've done. I'm sorry," Banks said. "To know that I took lives hurts me," he said. He said he knew he had also hurt the victims' family members. "This is justified," Banks said. "I've done one good thing in my life and that is to become a Jehovah's Witness. For that, I'm eternally grateful."

Banks, strapped to a gurney with IV lines attached to his arms, acknowledged witnesses to his execution, including his attorney, Tom Hird of the Federal Public Defender's Office in Oklahoma City, and an unidentified spiritual adviser. "I'm thankful everybody's here. I appreciate that," he said. Banks singled out Tulsa County Sheriff Stanley Glanz, who also witnessed his execution. "I haven't seen you in years, decades," Banks said with a smile.

Banks closed his eyes and took several deep breaths as the lethal drugs were injected into his body. He appeared to grimace briefly before he stopped breathing and his body went limp. No one from the victim's family witnessed Banks' execution. Attorney General Scott Pruitt issued a statement beforehand that said his thoughts were with the victim's family. "Anthony Banks brutally ended the life of an innocent young woman and has proven his willingness to continue committing violent crimes," Pruitt said.

About five people protested the execution at the governor's mansion in Oklahoma City. One of the protesters, D.W. Hearn, 68, held a rosary. He said he was praying for the man about to be executed, the man's family and the victim's family. He said he believes Oklahoma will eventually abolish the death penalty.

Travis was abducted from the parking lot of a Tulsa apartment complex and was later raped and shot in the head. Her partially clothed body was found in a roadside ditch on the city's north side the morning after her disappearance. Banks and a co-defendant, Allen Wayne Nelson, 54, were charged in August 1997, when their DNA was detected in evidence found on Travis' body and clothing. A 12-member jury convicted Nelson of first-degree murder and sentenced him to life in prison.

Banks was already in prison following his conviction for the 1978 slaying of David Fremin, who was shot and killed during an armed robbery. Banks was convicted of first-degree murder by a Tulsa County jury that imposed the death penalty in that case. But the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered a new trial in 1994, saying prosecutors failed to disclose evidence to the defense that the jury could have used to find Banks innocent. The court also said Banks received ineffective counsel. Rather than face the possibility of being sentenced to death again, Banks pleaded guilty to the murder charge in exchange for a sentence of life in prison.

In July, Banks waived his right to ask the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board to commute his death sentence to life in prison.

The state has executed three other death row inmates this year. Steven Ray Thacker, 42, was executed on March 12 for the 1999 death of a woman whose credit cards he used to buy Christmas presents for his family. James Lewis DeRosa, 36, was executed on June 18 for the October 2000 stabbing deaths of a couple on whose ranch he had worked. And Brian Darrell Davis, 39, was executed on June 25 for raping and killing his girlfriend's mother in 2001. No other executions are scheduled.

"Oklahoma executes inmate Anthony Banks for murder in 1979." (Tue Sep 10, 2013 7:47pm EDT)

(Reuters) - Oklahoma executed a man on Tuesday for the rape and murder of a Tulsa woman in 1979, a crime that went unsolved for 18 years until new DNA techniques led to his conviction. Anthony Banks, 60, was pronounced dead at 6:07 p.m. (2307 GMT). Banks was convicted and sentenced to death for the June 6, 1979, murder of Sun I. Kim Travis, a 24-year-old Korean woman who he raped, beaten, shot in the face and dumped in a ditch, according to court documents.

"Execution date set for killer whose crime went unsolved for 20 years," by Rachel Petersen. (Jun 14, 2013)

McALESTER — An execution date has been set for a death row inmate whose crime went unsolved for two decades. Anthony Rozelle Banks, 60, is scheduled to be executed Sept. 10 via lethal injection in the death chamber at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary.

On May 20, the last appeal filed by Banks was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court. “The defendant has exhausted all state and federal appeals,” said Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt in his execution date request to the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals. “Therefore, the state respectfully requests this court set an execution date ...”

Banks was convicted in 1999 of the murder of Sun I. Kim Travis in Tulsa. Travis was kidnapped from her Tulsa apartment in June 1979. She was raped, beaten and shot in the face. Her body was dumped in a ditch. Prior to her death, Travis, a Korean national, met her husband when he was serving in the American military on deployment in Korea. “The two married and moved to Tulsa, where it appears they lived happily,” court records state. “At first, the police knew very little. Mrs.’ Travis’s husband was at home preparing dinner when he looked out the window and saw his wife’s car pull into the apartment complex’s parking lot, apparently followed by another vehicle. “After several minutes passed and she didn’t come inside, he went out to check on her. She was nowhere to be seen.

Mr. Travis sensed something was amiss because the car was parked at an odd angle with the headlights still on and the driver’s door open. The pillow that Mrs. Travis kept on the driver’s seat was lying in the street.” Court records indicate that the next morning, a man on a tractor discovered her body in a roadside ditch. “She had suffered a gunshot would to the head, and her face bore recent bruises,” court records state. “Her blouse was missing and her panties were ripped and lying by her feet.” The medical examiner found semen on her clothes and in her body.

The murder case of Travis had gone unsolved until Tulsa police used DNA evidence to link Banks and Allen Wayne Nelson, 53, to the woman’s rape and murder. Tulsa police used DNA testing from two different analysts on sperm from the slain woman’s body and clothes to link Banks and Nelson to the crime. DNA testing indicated that both men had raped her, court records state. “One of the analysts said the likelihood of a random African American individual matching the DNA sequence attributed to Mr. Banks was on the order of 1 in 300 billion,” court records state.

In 1997, Banks and Nelson were charged with her murder. Nelson was sentenced to life in prison and in October 1999, Banks was convicted and sentenced to death. When convicted, Banks was already serving a life sentence for killing a convenience store clerk, David Fremin, in 1978. In a court hearing, Banks admitted to shooting Fremin in the head during a holdup.

Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish Death Penalty

Oklahoma Attorney General (News Release)

News Release - Anthony R. Banks Execution

09/10/2013

OKLAHOMA CITY – Anthony R. Banks – Sept. 10 at 6 p.m. Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester.

Name: Anthony Rozelle Banks

DOB: 07/05/1952

Sex: Male

Age at Date of Crime: 26

>BR> Victim(s): Sun Travis, 25, DOB: 05/10/1954

Date of Crime: 06/06/1979

Date of Sentence: 10/28/1999

Crime Location: Victim kidnapped at 1117 S College in her apartment complex parking lot. Her body was found in a field in the 1800 block of E 36 St. North in Tulsa.

Judge: Thomas C. Gillert

Prosecuting: Doug Drummond, Chad A. Greer

Defending: James C. Bowen, Mark Matheson

Circumstances Surrounding Crime: Banks was found guilty by a jury of his peers for the first-degree murder and rape of Sun Travis, 25, of Tulsa. Sun Travis was returning home from work when she was kidnapped, raped and brutally murdered. Her body was discovered the next day in a roadside ditch. In November 1979, Banks was in custody on unrelated charges when he gave a statement to police implicating an accomplice in the murder of Travis. There was not enough evidence to charge Banks until DNA testing became available.

In 1997, DNA testing was conducted. The results confirmed Banks’ participation in the kidnaping, rape and murder of Sun Travis. Banks had at least eight prior violent felony convictions, ranging from armed robbery to a second first-degree murder conviction.

Statement from Attorney General Scott Pruitt: “Anthony Banks brutally ended the life of an innocent young woman and has proven his willingness to continue committing violent crimes,” Attorney General Scott Pruitt said. “My thoughts are with the family and friends of Sun Travis, who lost a loved one due to Banks’ heinous actions.”

Wikipedia: Oklahoma Executions

A total of 103 individuals convicted of murder have been executed by the State of Oklahoma since 1976, all by lethal injection:

1. Charles Troy Coleman 10 September 1990 John Seward

2. Robyn Leroy Parks 10 March 1992 Abdullah Ibrahim

3. Olan Randle Robinson 13 March 1992 Shiela Lovejoy, Robert Swinford

4. Thomas J. Grasso 20 March 1995 Hilda Johnson

5. Roger Dale Stafford 1 July 1995 Melvin Lorenz, Linda Lorenz, Richard Lorenz, Isaac Freeman, Louis Zacarias, Terri Horst, David Salsman, Anthony Tew, David Lindsey

6. Robert Allen Brecheen [1][2][3] 11 August 1995 Marie Stubbs

7. Benjamin Brewer 26 April 1996 Karen Joyce Stapleton

8. Steven Keith Hatch 9 August 1996 Richard Douglas, Marilyn Douglas

9. Scott Dawn Carpenter 7 May 1997 A.J. Kelley

10. Michael Edward Long 20 February 1998 Sheryl Graber, Andrew Graber

11. Stephen Edward Wood 5 August 1998 Robert B. Brigden

12. Tuan Anh Nguyen 10 December 1998 Amanda White, Joseph White

13. John Wayne Duvall 17 December 1998 Karla Duvall

14. John Walter Castro 7 January 1999 Beulah Grace, Sissons Cox, Rhonda Pappan

15. Sean Richard Sellers 4 February 1999 Paul Bellofatto, Vonda Bellofatto, Robert Bower

16. Scotty Lee Moore 3 June 1999 Alex Fernandez

17. Norman Lee Newsted 8 July 1999 Larry Buckley

18. Cornel Cooks 2 December 1999 Jennie Elva Ridling

19. Bobby Lynn Ross 9 December 1999 Steven Mahan

20. Malcolm Rent Johnson 6 January 2000 Ura Alma Thompson

21. Gary Alan Walker 13 January 2000 Eddie O. Cash, Valerie Shaw-Hartzell, Jane Hilburn, Janet Jewell, Margaret Bell Lydick, DeRonda Gay Roy

22. Michael Donald Roberts 10 February 2000 Lula Mae Brooks

23. Kelly Lamont Rogers 23 March 2000 Karen Marie Lauffenburger

24. Ronald Keith Boyd 27 April 2000 Richard Oldham Riggs

25. Charles Adrian Foster 25 May 2000 Claude Wiley

26. James Glenn Rodebeaux 1 June 2000 Nancy Rose Lee McKinney

27. Roger James Berget 8 June 2000 Rick Lee Patterson

28. William Clifford Bryson 15 June 2000 James Earl Plantz

29. Gregg Francis Braun 10 August 2000 Gwendolyn Sue Miller, Barbara Kchendorfer, Mary Rains, Pete Spurrier, Geraldine Valdez

30. George Kent Wallace 10 August 2000 William Von Eric Domer, Mark Anthony McLaughlin

31. Eddie Leroy Trice 9 January 2001 Ernestine Jones

32. Wanda Jean Allen 11 January 2001 Gloria Jean Leathers

33. Floyd Allen Medlock 16 January 2001 Katherine Ann Busch

34. Dion Athansius Smallwood 18 January 2001 Lois Frederick

35. Mark Andrew Fowler 23 January 2001 John Barrier, Rick Cast, Chumpon Chaowasin

36. Billy Ray Fox 25 January 2001

37. Loyd Winford Lafevers 30 January 2001 Addie Mae Hawley

38. Dorsie Leslie Jones, Jr. 1 February 2001 Stanley Eugene Buck, Sr.

39. Robert William Clayton 1 March 2001 Rhonda Kay Timmons

40. Ronald Dunaway Fluke 27 March 2001 Ginger Lou Fluke, Kathryn Lee Fluke, Suzanna Michelle Fluke

41. Marilyn Kay Plantz 1 May 2001 James Earl Plantz

42. Terrance Anthony James 22 May 2001 Mark Allen Berry

43. Vincent Allen Johnson 29 May 2001 Shirley Mooneyham

44. Jerald Wayne Harjo 17 July 2001 Ruther Porter

45. Jack Dale Walker 28 August 2001 Shely Deann Ellison, Donald Gary Epperson

46. Alvie James Hale, Jr. 18 October 2001 William Jeffery Perry

47. Lois Nadean Smith 4 December 2001 Cindy Baillee

48. Sahib Lateef Al-Mosawi 6 December 2001 Inaam Al-Nashi, Mohamed Al-Nashi

49. David Wayne Woodruff 21 January 2002 Roger Joel Sarfaty, Lloyd Thompson

50. John Joseph Romano 29 January 2002

51. Randall Eugene Cannon 23 July 2002 Addie Mae Hawley

52. Earl Alexander Frederick, Sr. 30 July 2002 Bradford Lee Beck

53. Jerry Lynn McCracken[10] 10 December 2002 Tyrrell Lee Boyd, Steve Allen Smith, Timothy Edward Sheets, Carol Ann McDaniels

54. Jay Wesley Neill 12 December 2002 Kay Bruno, Jerri Bowles, Joyce Mullenix, Ralph Zeller

55. Ernest Marvin Carter, Jr. 17 December 2002 Eugene Mankowski

56. Daniel Juan Revilla 16 January 2003 Mark Gomez Brad Henry

57. Bobby Joe Fields 13 February 2003 Louise J. Schem

58. Walanzo Deon Robinson 18 March 2003 Dennis Eugene Hill

59. John Michael Hooker 25 March 2003 Sylvia Stokes, Durcilla Morgan

60. Scott Allen Hain 3 April 2003 Michael William Houghton, Laura Lee Sanders

61. Don Wilson Hawkins, Jr. 8 April 2003 Linda Ann Thompson

62. Larry Kenneth Jackson 17 April 2003 Wendy Cade

63. Robert Wesley Knighton 27 May 2003 Richard Denney, Virginia Denney

64. Kenneth Chad Charm 5 June 2003 Brandy Crystian Hill

65. Lewis Eugene Gilbert II 1 July 2003 Roxanne Lynn Ruddell

66. Robert Don Duckett 8 July 2003 John E. Howard

67. Bryan Anthony Toles 22 July 2003 Juan Franceschi, Lonnie Franceschi

68. Jackie Lee Willingham 24 July 2003 Jayne Ellen Van Wey

69. Harold Loyd McElmurry III 29 July 2003 Rosa Vivien Pendley, Robert Pendley

70. Tyrone Peter Darks 13 January 2004 Sherry Goodlow

71. Norman Richard Cleary 17 February 2004 Wanda Neafus

72. David Jay Brown 9 March 2004 Eldon Lee McGuire

73. Hung Thanh Le 23 March 2004 Hai Hong Nguyen

74. Robert Leroy Bryan 8 June 2004 Mildred Inabell Bryan

75. Windel Ray Workman 26 August 2004 Amanda Hollman

76. Jimmie Ray Slaughter 15 March 2005 Melody Sue Wuertz, Jessica Rae Wuertz

77. George James Miller, Jr. 12 May 2005 Gary Kent Dodd

78. Michael Lannier Pennington 19 July 2005 Bradley Thomas Grooms

79. Kenneth Eugene Turrentine 11 August 2005 Avon Stevenson, Anita Richardson, Tina Pennington, Martise Richardson

80. Richard Alford Thornburg, Jr. 18 April 2006 Jim Poteet, Terry Shepard, Kevin Smith

81. John Albert Boltz 1 June 2006 Doug Kirby

82. Eric Allen Patton 29 August 2006 Charlene Kauer

83. James Patrick Malicoat 31 August 2006 Tessa Leadford

84. Corey Duane Hamilton 9 January 2007 Joseph Gooch, Theodore Kindley, Senaida Lara, Steven Williams

85. Jimmy Dale Bland 26 June 2007 Doyle Windle Rains

86. Frank Duane Welch 21 August 2007 Jo Talley Cooper, Debra Anne Stevens

87. Terry Lyn Short[4] 17 June 2008 Ken Yamamoto

88. Jessie Cummings 25 September 2008 Melissa Moody

89. Darwin Brown 22 January 2009 Richard Yost

90. Donald Gilson 14 May 2009 Shane Coffman

91. Michael DeLozier 9 July 2009 Orville Lewis Bullard, Paul Steven Morgan

92. Julius Ricardo Young 14 January 2010 Joyland Morgan, Kewan Morgan

93. Donald Ray Wackerly II 14 October 2010 Pan Sayakhoummane

94. John David Duty 16 December 2010 Curtis Wise

95. Billy Don Alverson 6 January 2011 Richard Kevin Yost

96. Jeffrey David Matthews 11 January 2011 Otis Earl Short Mary Fallin

97. Gary Welch 5 January 2012 Robert Dean Hardcastle

98. Timothy Shaun Stemple 15 March 2012 Trisha Stemple

99. Michael Bascum Selsor 1 May 2012 Clayton Chandler

100. Michael E. Hooper 14 August 2012 Cynthia Jarman, Timothy Jarman, Tonya Jarman

101. Garry T. Allen 06 November 2012 Gail Titsworth

102. George Ochoa 04 December 2012 Francisco Morales, Maria Yanez

103. Steven Ray Thacker 12 March 2013 Laci Dawn Hill

104. James L. DeRosa 18 June 2013 Curtis and Gloria Plummer

105. Brian Darrell Davis 25 June 2013 Jody Sanford

106. Anthony R. Banks 10 September 2013 Sun Kim Travis

Banks v. State, 701 P.2d 418, (Okla. Crim. App. 1985). (Direct Appeal-Robbery/Murder)

OVERVIEW: In a joint trial, defendant was convicted of the first-degree murder of a store clerk, which was committed in the course of a robbery with his co-defendant. Defendant alleged that reversible error occurred in jury selection, the denial of his motion for severance, admission of statements by his co-defendant, and in sentencing. On appeal, the court affirmed defendant's conviction and sentence. No error occurred in the jury selection process. The questions asked of the jurors during voir dire were appropriate to empanel a jury that would be asked to consider a death sentence. The trial court acted within its discretion in jury selection. Improper comments by the State during voir dire did not warrant reversal in light of the overwhelming evidence against defendant. No abuse of discretion by the trial court occurred that was related to the admittance of evidence at trial or during sentencing. In the sentencing phase of defendant's trial, evidence of aggravating circumstances was admitted in compliance with Okla. Stat. tit. 21, §§ 701.10, 701.12(5) (1981) and the penalty of death was proportionate under Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 701.13 (1981) to the penalty imposed in similar cases. The court affirmed defendant's conviction and sentence by the trial court.

In the early morning hours of April 11, 1978, Anthony Rozelle Banks and his brother, Walter Thomas Banks, robbed a convenience store at the corner of 36th and Sheridan streets in Tulsa. During that robbery Anthony shot and killed the clerk on duty, David Paul Fremin. The two brothers were jointly charged with and tried in the Tulsa County District Court, Case No. CRF-79-3393, for First Degree Murder, the Honorable Joe Jennings, presiding. The jury found both guilty as charged and sentenced Walter to life imprisonment. The sentence for Anthony was death. It is from this judgment and sentence that Anthony Banks has perfected this appeal. We affirm. The case went unresolved for fifteen months when the appellant, having been arrested for an unrelated armed robbery, offered to give the police some information about Fremin's murder in hopes of getting more lenient treatment for the robbery. In the subsequent investigation, police were able to identify a fingerprint lifted from the crime scene as that of Anthony Banks. They also located Traci Banks, who had been Anthony's girlfriend at the time of the murder and who had been living with Anthony and Walter in their Tulsa apartment.

Traci testified at trial that about three o'clock in the morning of April 11, 1978, Walter and Anthony left the apartment to "go do something." Anthony returned about 5:00 a.m. with a small brown box containing money, food stamps, and blank money orders. He also carried a man's wallet containing the driver's license of David Paul Fremin. Traci recognized that name the next day when she read newspaper accounts of the murder. As she helped Anthony count the contents of the box, he told her that he and Walter had robbed the Git-N-Go Store at 36th and Sheridan, Walter keeping watch outside while Anthony killed the clerk in order to avoid being identified. Walter's testimony was substantially the same. Medical testimony established that one of the victim's two head wounds was superficial while the other was certainly fatal. Both were inflicted from very close range almost directly above the victim's head. The locations and directions of the wounds were consistent with the notion that Fremin had been sitting or kneeling when shot.

I.

The appellant first challenges the constitutionality of Oklahoma's death penalty statute. 21 O.S.1981, § 701.7. He contends the statute must be invalidated because it does not further a compelling state interest that cannot be fulfilled by less drastic means. The United States Supreme Court in Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 96 S. Ct. 2909, 49 L. Ed. 2d 859 (1976), and this Court in Burrows v. State, 640 P.2d 533 (Okl.Cr.1982), Glidewell v. State, 663 P.2d 738 (Okl.Cr.1983), and Davis v. State, 665 P.2d 1186 (Okl.Cr.1983) rejected this argument. We do not adopt it now.

II.

Burrows also disposes of appellant's second assignment of error, that is, that the death penalty is unconstitutionally arbitrary because of the discretion that prosecutors retain with regard to seeking the death penalty. This assignment of error is without merit.

III.

The appellant next alleges that six prospective jurors were improperly dismissed for cause in violation of the rule set forth in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S. Ct. 1770, 20 L. Ed. 2d 776 (1968). Therein the United States Supreme Court determined that HN1Go to the description of this Headnote.the death penalty could not be carried out if the jury that imposed it had been selected by excluding for cause venirepersons who expressed general objections to the death penalty or conscientious or religious scruples against its infliction. Id. at 521, 88 S. Ct. at 1776, 20 L. Ed. 2d at 784. The most that can be required of a venireperson is that he be willing to consider all the penalties provided by law and that he not be irrevocably committed before the trial has begun. In the trial below, the judge systematically asked each juror the following question: "In a case where the law and the evidence warrant, in a proper case, could you, without doing violence to your conscience, agree to a verdict imposing the Death Penalty?" Although this Court has implicitly approved of this question by affirming cases in which it was used and in which it otherwise appeared that the dismissed venirepersons were firm in their resolve not to consider the death penalty, see, e.g., Parks v. State, 651 P.2d 686 (Okl.Cr.1982), the question is confusing. Violence done to one's conscience is not the point of the Witherspoon voir dire examination. As this writer has said in dissent, HN2Go to the description of this Headnote.the only legitimate concern is whether each jury member will consider the imposition of the death sentence, as one of the alternatives provided by state law, should the case be appropriate for that punishment. Davis v. State, 665 P.2d 1186, 1204 (Okl.Cr.1983) (Brett, J., dissenting). 1

1 Ambiguous questions are difficult to answer clearly, and clarity is extremely important in Witherspoon examination. Therefore we suggest that compound questions, such as the one regarding violence to one's conscience, be avoided. For example, the following approach, to this writer, seems preferable to that mentioned heretofore: The laws of Oklahoma permit only two possible punishments for persons found guilty of first degree murder: either imprisonment for life or death. Do you have feelings about capital punishment that would prevent or substantially impair you from considering either of these punishments if the defendant were found guilty of first degree murder? Such a question may help the trial judge to discover substantial juror bias either for or against capital punishment.

In the present case, however, a second question was also asked of each juror: If you found beyond a reasonable doubt that the Defendant was guilty of Murder in the First Degree, and if under the evidence and the facts and the circumstances of the case the law would permit you to consider a sentence of Death, are your reservations about the Death Penalty such that regardless of the law, the facts and the circumstances of the case, you would not inflict the Death Penalty? Three of the jurors challenged herein for cause, veniremen Moats, Lair, and Parker, responded clearly and unambiguously that under no circumstances would they vote to inflict the death penalty. They were clearly committed to vote against the death penalty regardless of the facts of the case; therefore, it was permissible to dismiss them for cause. See Coleman v. State, 668 P.2d 1126 (Okl. Cr.1983); Chaney v. State, 612 P.2d 269 (Okl.Cr.1980), modified on other grounds, sub. nom., Chaney v. Brown, 730 F.2d 1334 (10th Cir. 1984).

Prospective juror Leek answered the former question, "I don't think I could sir," and the latter question, "I don't believe I would, sir." We affirmed the dismissal for cause of a potential juror who answered similarly in Dutton v. State, 674 P.2d 1134 (Okl.Cr.1984). Thus it was not error to dismiss venireman Leek for cause under Witherspoon.

Juror Boyd was also dismissed for cause during voir dire. The examination was conducted, in pertinent part, as follows: THE COURT: If it becomes necessary to consider punishment in this case, in a case where the law and the evidence warrant, in a proper case, could you without doing violence to your conscience agree to a verdict imposing the death penalty? MR. BOYD: That I'd have to give thought. THE COURT: I will ask you to give it thought right now. MR. BOYD: Well, I don't think I could. THE COURT: You tell me if you were selected as a juror in this or any other case in which a defendant was charged with First Degree Murder and you and your fellow jurors found beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant was guilty of Murder in the First Degree, under the evidence, facts and circumstances of the case, the law were to permit you to consider a sentence of death, your reservations about the death penalty are such that regardless of the facts or regardless of the circumstances of the case you would not inflict the death penalty? MR. BOYD: Well, that would be taking a life; I don't feel like I should do that. It would be like I was taking a life too. THE COURT: Your answer would be you would not inflict the death penalty? MR. BOYD: I guess I wouldn't. It appears to this Court that juror Boyd was committed to vote against the death penalty regardless of the law and that it was therefore proper to permit him to be dismissed for cause.

Our determination of this issue is further supported by the recent United States Supreme Court decision in Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 105 S. Ct. 844, 83 L. Ed. 2d 841 (1985). Therein the Court held that HN3Go to the description of this Headnote.the proper standard for determining when a prospective juror may be excluded for cause because of his or her views on capital punishment is that the juror's views would "'prevent or substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath.'" Id. at 852. The Court further stated that a juror's bias need not be proved with "unmistakable clarity;" neither must the juror express an intention to vote against the death penalty "automatically." Id. This Court has previously noted that HN4Go to the description of this Headnote.trial judges, having heard the juror's voice inflection and viewed his demeanor, may be fairly convinced of a juror's bias when such bias appears in a written record to be less than "unmistakably clear." See Davis v. State, 665 P.2d 1186 (Okl.Cr.1983). The majority in Witt also observed that determinations of juror bias simply cannot be reduced to "question and answer sessions which obtain results in the manner of a catechism." Witt, 105 S. Ct. at 852. In the present case, therefore, we find that the trial judge did not abuse his discretion in dismissing these jurors for cause because their answers established the fact that their views about capital punishment would have prevented or substantially impaired the performance of their duties as jurors in accordance with the instructions and the oath.

Nor was it error in this case to refuse the appellant an opportunity to rehabilitate the excused veniremen. HN5Go to the description of this Headnote.The manner and extent of voir dire examination rests largely in the sound discretion of the trial judge. McFatridge v. State, 632 P.2d 1226 (Okl.Cr.1981). This Court held in Vardeman v. State, 54 Okl.Cr. 329, 20 P.2d 194 (1933): HN6Go to the description of this Headnote.After the court has asked jurors as to their legal qualifications, it is hardly necessary for the state or defendant's counsel to ask them the same questions, although sometimes this is done. When any part of the questioning is denied or excluded, in order to preserve the question the proper procedure for defendant's counsel is to dictate into the record the questions he desires to ask the jurors, and obtain a ruling of the court thereon, thereby enabling this Court to determine if the trial court abused its discretion in refusing to permit counsel to ask the questions. Id. at 330, 20 P.2d at 195. See also 632 P.2d at 1229. In the present case the defendant failed to make a record of the questions he intended to ask the excused veniremen, therefore we do not have a proper record from which to review the trial court's decision to disallow further questioning. Reviewing the record before us in this regard we do not find any abuse of judicial discretion. Further questioning in this difficult area may only have served to confuse the prospective jurors when the pertinent questions had been asked and clearly answered. Cf. Chaney v. State, 612 P.2d 269 (Okl.Cr.1980) ("one of the tendencies of voir dire in a challenge situation is that the longer it lasts the less objective it becomes . . . ."), modified on other grounds, sub nom. Chaney v. Brown, 730 F.2d 1334 (10th Cir. 1984).

The appellant also challenges the dismissal for cause of a sixth juror, Ms. Bellamy, as a violation of Witherspoon. She was not dismissed because of her inability to consider imposing the death penalty, however, so such a challenge is not to the point. Ms. Bellamy was dismissed because the trial judge believed that she might be unable to devote her full attention to the proceedings. She stated that she had two small children for whose care she had made arrangements during the scheduled week of jury duty. She also stated that if the trial ran on into a second week it would cause her some problems. She said she could make further arrangements but that such necessity might cause her difficulty and that she preferred to be excused from sitting on the case. To force her to sit even for the first week of trial might well have caused in her some ill will resulting in prejudice toward the defendant. It was not an abuse of the trial judge's discretion to dismiss her for cause. See Washington v. State, 568 P.2d 301 (Okl.Cr.1977).

IV.

In his fourth assignment of error the appellant charges that reversible error occurred during the voir dire examination of the jury due to improper comments made by the prosecutor. Mr. Jerry Truster, an assistant district attorney, asked a prospective juror, within the hearing of the whole panel, if she believed that victims of crimes have rights. After objections and requests for admonition were denied the prosecutor continued the line of questioning about victims having rights like those of the defendant. He asked the questions yet another time before the panel was finally selected. These comments and questions are improper and were asked with the intention of inflaming the prejudices of the jury panel. This Court does not approve of argument or comment so intended. Tobler v. State, 688 P.2d 350 (Okl.Cr.1984); Ward v. State, 633 P.2d 757 (Okl.Cr.1981). Defense objections should have been sustained and the jury admonished to disregard such comments. Still we are unable to say that these comments alone require modification or reversal. The evidence in the case is overwhelming. The error was not manifestly prejudicial. See Hunter v. State, 637 P.2d 871 (Okl.Cr.1981).

V.

The appellant next alleges reversible error occurred during jury selection because of a reference to the pardon and parole system. One of the veniremen was asked if she knew or was related to a certain criminal defendant with the same surname as hers. She replied that she did not know that person but that she had read in the newspaper that he was eligible for parole. There was no other reference to the possibility of pardon or parole through the end of the trial. While there was no admonition given the jury on this point we do not find this single brief, unsolicited mention of the parole system during voir dire to be prejudicial. The appellant further contends that the prosecutor drew attention to the parole possibility when questioning another prospective juror during voir dire. We disagree. The challenged question can only be understood as a reference to the bifurcated nature of the trial itself. These contentions are thus without merit.

VI.

In his sixth assignment of error the appellant alleges that photographs of the crime scene and the murder victim were erroneously admitted at trial because they were irrelevant and unduly gruesome. HN7Go to the description of this Headnote.The admissibility of demonstrative evidence is a question of legal relevance that is within the discretion of the trial court, whose decisions will not be disturbed on appeal absent an abuse of that discretion. Assadollah v. State, 632 P.2d 1215 (Okl.Cr.1981). The photographs in question accurately depicted the scene of the crime, the position of the victim's body, and the location of the wounds upon the victim's head. They tended to support testimony that the murder was committed during a robbery and that the victim was shot from directly overhead. We cannot say that these black and white photographs were more prejudicial than probative; therefore this assignment of error is without merit. Glidewell v. State, 626 P.2d 1351 (Okl.Cr.1981); Deason v. State, 576 P.2d 778 (Okl.Cr.1978).

VII.

The appellant next asserts that it was reversible error to refuse to grant his motion for a severance due to the admission at trial of extrajudicial statements of his co-defendant. He contends that statements made by his brother Walter on the witness stand prejudiced the jury against him in violation of Bruton v. United States, 391 U.S. 123, 88 S. Ct. 1620, 20 L. Ed. 2d 476 (1968). In that case the Supreme Court held that HN8Go to the description of this Headnote.it was reversible error in a joint trial to admit into evidence a co-defendant's extrajudicial confession when that statement implicates the defendant. In such a case a severance should be granted. The present case does not fall within the purview of Bruton, however, because the objected to statements were not confessions. Walter's first statement to the police corroborated Anthony's alibi without inculpating himself. The second, which was not recorded but was put into evidence at trial through Walter's testimony, consisted entirely of Walter's admission to police that his prior statement was a lie. Neither statement tended to inculpate Anthony. HN9Go to the description of this Headnote.When a co-defendant's extrajudicial statements do not implicate the defendant, the trial court does not abuse its discretion by denying a severance. See Riggle v. State, 585 P.2d 1382 (Okl.Cr.1978). In addition, where, as here, confessions are not involved, the mere fact that a co-defendant attempts to escape punishment by inculpating the defendant is not sufficient ground for requiring a severance. Hinds v. State, 514 P.2d 947 (Okl.Cr.1973). We leave the decision to grant or deny a severance to the discretion of the trial court, and absent an abuse thereof resulting in prejudice to the defendant we will not disturb that decision on appeal. Menefee v. State, 640 P.2d 1381 (Okl.Cr.1982). The appellant has failed to show any prejudice resulting from the joint trial; therefore this assignment is without merit.

VIII.

The appellant next alleges that he was denied a fair trial due to improper comments made by the prosecutor throughout the trial. The prosecutor more than once referred to the appellant as a "snitch", commented upon the appellant's truthfulness during cross-examination, and insinuated that the appellant was having an extramarital affair. Such comments violate three of the criteria of the American Bar Association Standards of Criminal Justice "The Prosecution Function" Section 5.8 which was adopted by this Court in Dupree v. State, 514 P.2d 425 (Okl.Cr.1973). But though these and other comments were improper, most of them either were not preserved for appeal because of failure to object or to request admonition of the jury, Tahdooahnippah v. State, 610 P.2d 808 (Okl.Cr.1980); Burrows v. State, 640 P.2d 533 (Okl.Cr.1982), or were cured by the trial judge's admonitions as to those comments. Holdge v. State, 586 P.2d 744 (Okl.Cr.1978). We have therefore reviewed the record for fundamental error only. Coleman v. State, 668 P.2d 1126 (Okl.Cr.1983). In light of the overwhelming evidence in this case we are unable to conclude that the improper comments prejudiced the jury. Nor is their cumulative effect such as would warrant reversal or modification. Robison v. State, 677 P.2d 1080 (Okl.Cr.1984); Sizemore v. State, 499 P.2d 486 (Okl.Cr.1972).

IX.

In his ninth assignment of error the appellant alleges that a judgment and sentence on a 1980 Armed Robbery conviction was erroneously admitted into evidence during the second stage of the trial. We need not address this issue, however, because two other previous convictions for armed robbery were introduced into evidence. Even if it was error to admit into evidence the 1980 conviction, there is no reasonable probability that this evidence contributed to the jury's sentence. The error, if any, was therefore harmless. See Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18, 87 S. Ct. 824, 17 L. Ed. 2d 705 (1967); Fahy v. Connecticut, 375 U.S. 85, 84 S. Ct. 229, 11 L. Ed. 2d 171 (1963).

X.

In his tenth assignment of error the appellant alleges that the trial court should have stricken allegation number two from the Bill of Particulars because of insufficient proof that Banks killed David Fremin in order to avoid arrest or prosecution. 21 O.S.1981, § 701.12(5). HN10Go to the description of this Headnote.The focus of this aggravating circumstance is the state of mind of the murderer; it is he who must have the purpose of avoiding or preventing lawful arrest or prosecution. Parks v. State, 651 P.2d 686 (Okl.Cr.1982). Traci Banks testified that Anthony told her he killed Fremin in order to avoid being identified. Her testimony clearly addressed the issue of Anthony's state of mind at the time of the murder and provided sufficient basis for the jury to find that this aggravating circumstance existed beyond a reasonable doubt. The tenth assignment of error is without merit.

XI.

In his eleventh assignment of error the appellant claims that the trial court should have granted his demurrer to the evidence showing that he would be a continuing threat to society. We disagree. In the second stage of the trial, the State presented evidence that Anthony Banks had been previously convicted of three felonies, each involving the use of firearms and threats of violence to others. This evidence is sufficient to show the aggravating circumstance charged. Eddings v. State, 616 P.2d 1159 (Okl.Cr.1980), reversed on other grounds, 455 U.S. 104, 102 S. Ct. 869, 71 L. Ed. 2d 1 (1982), modified, 688 P.2d 342 (Okl.Cr.1984). The manner in which the murder was committed also supports a finding of this aggravating circumstance. Robison v. State, 677 P.2d 1080 (Okl.Cr.1984). To support his allegation of error the appellant cites only Boutwell v. State, 659 P.2d 322 (Okl.Cr.1983). We modified the death sentence to life imprisonment in that case because of improper instruction on one of the aggravating circumstances. That ruling does not help the appellant's contention herein because there was no error in the given instructions. The eleventh assignment of error is therefore without merit.

XII. The appellant next asserts that his motion to strike allegation number three from the Bill of Particulars should have been granted. He contends that the Bill of Particulars must include statements of the evidence that the State intends to introduce to show aggravation. He relies on the language of 21 O.S.1981, § 701.10 which reads in pertinent part: HN11Go to the description of this Headnote.Only such evidence in aggravation as the State has made known to the defendant prior to his trial shall be admissible. The purpose of the Bill of Particulars is to allow the accused to prepare a defense. The defendant herein was notified on January 26, 1981, that the State would seek the death penalty against him and which aggravating circumstances it would seek to prove, the Bill of Particulars having been filed previously. On February 2, two weeks before the trial commenced, the State made known during a hearing on motions that it intended to introduce Judgments and Sentences from three prior convictions for Robbery with Firearms in order to show that Banks would be a continuing threat to society. The prosecutors also stated that they would rely on the evidence from their case in chief in order to prove the other aggravating circumstances. At the February 17th trial, the State did in fact introduce the evidence it had specified and in the manner promised. The notice given in this case was sufficient to permit Banks to prepare his defense; therefore this assignment is without merit. The appellant also challenges the constitutionality of the aggravating circumstance that he would probably be a continuing threat to society. He asserts that it is vague and overbroad. We do not agree. See Johnson v. State, 665 P.2d 815 (Okl.Cr.1982).

XIII.

In addition to the arguments raised by the appellant we must HN12Go to the description of this Headnote.make three determinations in review of the death sentence imposed in this case: whether the sentence of death was imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor; whether the evidence supports the jury's or judge's finding of a statutory aggravating circumstance; and whether the sentence of death is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime and the defendant. 21 O.S.1981, § 701.13(c). We have fully reviewed the transcript and find it devoid of prejudice or bias. While there were some improper comments we are confident that they did not influence the passions of the jury or otherwise prejudice the jury against the appellant.

Our second determination regards the sufficiency of the evidence showing aggravating circumstances. The jury was instructed on three aggravating circumstances: (1) the defendant was convicted of prior felonies involving the use or threat of violence to the person; (2) the murder was committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest or prosecution; and, (3) the existence of a probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society. Traci Bank's testimony that Anthony killed David Fremin to avoid being identified is sufficient to support a finding that the murder was committed to avoid arrest or prosecution. The State introduced three certified Judgments and Sentences for Armed Robbery that were final at the time of trial below. Any one of these would be sufficient to support the jury's finding that he had been convicted of prior felonies involving the use or threat of violence to the person. Both the manner in which the murder was committed and the prior armed robbery convictions support a finding that Banks would probably commit future acts of violence constituting a continuing threat to society.

Finally, our third determination concerns the proportionality of the sentence in this case as compared to those in similar cases. In Hays v. State, 617 P.2d 223 (Okl.Cr.1980), the defendant shot the attendant of a shoe store twice in the head at close range during a robbery. The entry wounds were below the left and right ears. The defendant had been convicted of several previous felonies and he offered no evidence or testimony at trial despite the fact that he took the witness stand in his own defense. His death sentence was affirmed. The present case is similar to Hays in that the defendant shot the victim twice in the head at close range during a robbery. While Anthony Banks was, unlike Hays, not intoxicated when he killed Fremin, the difference does not significantly affect the proportionality between the two. In Parks v. State, 651 P.2d 686 (Okl.Cr.1982), the defendant killed a filling station attendant who had written down his license plate number. Parks feared that the attendant would discover that the credit card he was using was not his own. The jury panel therein found only one of the three charged aggravating circumstances: that the murder was committed to avoid prosecution. There were recorded telephonic conversations in which the defendant stated that he killed the attendant for that very purpose. The death sentence was affirmed on appeal.

In the present case Anthony Banks told his girlfriend that he killed the store attendant in order to avoid being identified in the robbery. The jury herein also found that he had committed the murder to avoid prosecution. We therefore find that the sentence given Anthony Rozelle Banks in this case is proportionate to similar cases in our state. We have also considered other cases in which the death penalty was affirmed for murders during armed robberies. Some of these murders involved multiple victims. See, e.g., Robison v. State, 677 P.2d 1080 (Okl.Cr.1984); Dutton v. State, 674 P.2d 1134 (Okl.Cr.1984); Coleman v. State, 668 P.2d 1126 (Okl.Cr.1983). These cases do not, however, tend to indicate that Bank's sentence is disproportionate.

The sentence of death by lethal drug injection in accordance with 22 O.S.1981, § 1014 is therefore AFFIRMED. PARKS, P.J., CONCURS IN RESULTS. BUSSEY, J., CONCURS.

Banks v. State, 43 P.3d 390 (2002 Okla. Crim. App. 2002). (Direct Appeal)

The court determined that viewing the evidence in a light most favorable to the State, the victim was taken forcibly from her parking lot, and transported to an apartment, where she was forced to have intercourse. Upon completion of these crimes, the victim was executed on the roadside. All the elements of felony murder in the commission of rape or kidnapping were satisfied. The only question for the jury was who committed the crimes. Defendant was one of the rapists, and he may or may not have actually pulled the trigger; if he did not, he may nevertheless have encouraged it. The court ruled that a rational jury could have convicted defendant of malice aforethought murder. Furthermore, any error in allowing a witness to be questioned after he attempted to invoke his Fifth Amendment privilege was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt, because it did not contribute to the jury's verdict. The evidence established that the aggravating circumstances outweighed the mitigating circumstances and that the jury was not influenced by passion, prejudice or any arbitrary factors. The judgment was affirmed.

CHAPEL, JUDGE:

Anthony Rozelle Banks was tried by jury and convicted of First Degree Murder in violation of 21 O.S.Supp. 1979, § 701.7, in the District Court of Tulsa County Case No. CF-97-3715. The jury found three aggravating circumstances: (1) that Banks was previously convicted of a felony involving the use or threat of violence to the person; (2) that the murder was committed to prevent lawful arrest or prosecution; and (3) that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. 1 In accordance with the jury's recommendation, the Honorable Thomas C. Gillert sentenced Banks to death.

1 21 O.S. 1991, § 701.12. The Bill of Particulars also alleged that Banks would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society. The jury did not find that this aggravator existed.

FACTS

At approximately 11:30 p.m. on June 6, 1979, Sun Travis was returning home from work. As she was driving into her apartment complex on South College Street, her husband (Steve Travis) heard their car muffler and peered out the apartment window. He saw Sun drive toward her designated parking spot, and also noticed a light blue or white hatchback automobile following her. A few minutes passed. Concerned, Steve walked outside to the lot, where he discovered the car parked in the wrong space with dome and headlights on. The pillow upon which Sun sat to drive was on the ground next to the car. Steve returned to the apartment and called the police. The next morning, Sun's lifeless and partially clothed body was found in the grass next to a nearby road. Sun had several bruises on her face. She had been killed by a gunshot wound to the head. In November 1979, Banks was in custody on unrelated charges when he asked to speak with the Tulsa County District Attorney about the Sun Travis murder. Banks's version of Sun Travis's death begins at approximately 11:00 p.m. on June 6, 1979: I was at a convenience store in my light blue AMC Hornet hatchback when Allen Nelson asked me for a ride. I drove him to what turned out to be Travis's apartment complex; Sun Travis pulled up in her car. Nelson exited my car, began talking to Travis, reentered my car with Travis, and requested that I drive them to the Apache Manor Apartments. Once there, Nelson and Travis entered the apartments while I drank beer and waited. Nelson and Travis, now shirtless, returned. I drove them around for about ten minutes, when Nelson asked me to stop the car on 36th Street, about three hundred yards from the entrance of the Comanche Apartments. Travis exited to the front of the car, Nelson to the rear, after which he circled around to the front and shot Travis in the head. Nelson returned to the car and asked me not to tell anyone. We drove away, until Nelson noticed a sewer drain and asked me to stop. He discarded Travis's blouse and purse in the drain, then returned to the car. I drove him home. 2

2 State's Exhibit 52 (paraphrased).

Despite Banks's statement, made in 1979, the Travis case remained open until 1997, when DNA analysis was performed on sperm samples obtained from the victim and her clothing. DNA analyst David Muniec testified that the sperm found on Travis's clothing was a mixture, matching both Banks's and Nelson's DNA. Muniec also testified that the sperm found on a vaginal swab matched Banks and the sperm on an anal swab matched Nelson. Forensic Chemist Julie Kempton also testified that the DNA found on Travis's pants was a mixture of Banks's and Nelson's DNA.

ISSUES RELATING TO PRETRIAL PROCEEDINGS

In Proposition VI, Banks argues that the trial court erred in allowing the State to prosecute him pursuant to the Second Amended Information, claiming prejudice in that he had no notice of the State's intent to prosecute him for first degree malice aforethought murder. This claim fails. On August 6, 1997, Banks was charged by Information with malice aforethought murder. At preliminary hearing on June 5, 1998, the State asked for, and without objection was granted, authority to amend the Information to charge Banks alternatively with malice aforethought murder and felony murder in the commission of the felonies of kidnapping and rape by force or fear. On June 25, 1998, the State mistakenly filed an Amended Information only charging Banks with felony murder, but corrected the error on August 27, 1999, by filing the Second Amended Information alleging malice aforethought murder and felony murder in the commission of kidnapping or rape by force or fear. Banks was not prejudiced as he was tried and convicted based upon the same evidence and charges that he was given notice of at preliminary hearing. 3 This Proposition is denied.

3 22 O.S. 1991, § 304 (information may be amended at any time as long as defendant's rights not materially prejudiced).

In Proposition II, Banks claims the trial court erred in overruling his motion to quash the search warrant issued to obtain his blood sample and suppress the DNA evidence it revealed. Banks contended that material misstatements existed in the affidavit for the search warrant. The trial court denied the motion, finding first that the misrepresentations were not material and second, that even without the offending language, other sufficient allegations supported a finding of probable cause. We agree. The affidavit correctly stated that semen had been obtained from a victim of sexual assault and murder. Probable cause to obtain Banks's blood was then established by his own admissions as outlined in the affidavit. Banks admitted accompanying Nelson "when Nelson committed the crimes." Thus, we find that assuming arguendo misrepresentation, the search warrant was supported by probable cause. 4

4 Skelly v. State, 1994 OK CR 55, 880 P.2d 401, 406 (warrant containing misrepresentations not voided where otherwise supported by probable cause).

ISSUES RELATING TO FIRST STAGE PROCEEDINGS

In Proposition I, Banks asserts that the evidence was insufficient to convict him of first degree murder. In evaluating evidence sufficiency, this Court considers it in a light most favorable to the State to determine whether "any rational trier of fact could have found the essential elements of the crime charged beyond a reasonable doubt." 5 Banks was alternatively charged with malice aforethought and felony murder in the commission of a kidnapping or forcible rape. The jury verdict form indicates Banks was found guilty of both and the evidence was sufficient to convict him of both 6.

5 Spuehler v. State, 1985 OK CR 132, 709 P.2d 202, 204-05 quoting Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 99 S. Ct. 2781, 61 L. Ed. 2d 560 (1979). 6 Lambert v. State, 1999 OK CR 17, 22, 984 P.2d 221, 229 (When a general verdict of first degree murder is returned, we consider the conviction to be a felony murder conviction. However, we will also address Banks's arguments regarding the sufficiency of the evidence for malice aforethought murder.)

In a light most favorable to the State, the evidence established that Banks and Nelson drove in Banks's car to Travis's apartment complex. Upon Travis's arrival, they forced her into their car, drove to the Apache Manor Apartments, forced her into an apartment, vaginally and anally raped her, returned to the car, and drove to 36th street where one or the other shot Travis in the head. HN1Go to the description of this Headnote.To convict Banks of malice aforethought murder, the jury had to find that he caused the unlawful death of a human with malice aforethought, 7 or aided and abetted another in the commission of the murder with the personal intent to kill, and with knowledge of the perpetrator's intent to kill. 8 "Aiding and abetting in a crime requires the State to show that the accused procured the crime to be done, or aided, assisted, abetted, advised or encouraged the commission of the crime." 9

7 21 O.S.Supp. 1976, § 701.7. 8 Torres v. State, 1998 OK CR 40, 962 P.2d 3, 15, cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1082, 119 S. Ct. 826, 142 L. Ed. 2d 683 (1999). 9 Id., quoting Spears v. State, 900 P.2d 431, 438 (Okl.Cr. 1995), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 1031, 116 S. Ct. 678, 133 L. Ed. 2d 527 (1995).

Banks argues that the evidence was insufficient because the State did not prove that he either shot Travis or aided and abetted Nelson when he shot her. In his police statement, Banks admitted his presence at all crime scenes, but claimed that Nelson acted unilaterally when he killed Travis. Banks's admitted presence at the crime scenes is consistent with the evidence. His denials of participation and/or culpability are not. Banks's DNA was found on evidence gathered from the victim's corpse and clothing, establishing his participation in forcible rape. Although the State admits uncertainty over whether Banks or Nelson actually shot Travis, a jury could have believed that Banks had done so--or that he, at a minimum, aided and abetted in the murder--especially given that Banks fingered Nelson as the sole sexual partner. What seems obvious is that Travis was killed to conceal her rapists' identities. Banks was one of the rapists. He may or may not have actually pulled the trigger; if he did not, he may nevertheless have encouraged Nelson to do so. As such, a rational jury could have convicted Banks of malice aforethought murder. HN2Go to the description of this Headnote.To convict Banks of felony murder, the jury had to find that the victim was killed in the commission of a kidnapping or forcible rape, either of which it could have easily done. To establish kidnapping, the State had to prove that the victim was unlawfully seized and secretly confined against her will. 10 To establish forcible rape, the State had to prove that the victim was forced to have intercourse by someone other than her spouse. 11

10 21 O.S. 1971, § 741. 11 21 O.S. 1971, § 1111.

The evidence established that Travis was murdered in the commission of both felonies. Viewing the evidence in a light most favorable to the State, the victim was taken forcibly from her parking lot, as indicated by the car lights and misplaced driving pillow. She was then transported to an apartment, where she was forced to have intercourse, as established by the bruises and semen on her body and the semen found on her clothes. Upon completion of these crimes, the victim was executed on the roadside. All elements of felony murder in the commission of rape or kidnapping were met. The only question for the jury was who committed the crimes. Banks was one of two perpetrators. He admitted his presence at all relevant locations; it was his car that was used to abduct the victim; it was partly his semen found on the victim's clothing and his semen alone on the vaginal swab.

Banks argues that the DNA evidence was inaccurate because his brother's DNA was not compared to that obtained from Travis. Although the DNA experts agreed that a sibling's DNA could skew statistical results, that observation did not change their opinion that Banks's DNA matched that obtained from the victim. Banks also claims that his brother's refusal to testify based upon the Fifth Amendment supports his brother's possible guilt for these crimes. The record indicates instead that Walter Banks (1) did not want to incriminate his brother and (2) did not want to return to his own prison term labeled a "snitch." Banks benefited from both arguments by allowing the jury to infer that his brother, Walter, could have committed the crimes. However, neither argument affected the sufficiency of the evidence to convict Banks of malice aforethought or felony murder in the commission of a kidnapping or forcible rape. This Proposition is denied.

In Proposition VIII, Banks argues that error occurred when the State was allowed to call Walter Banks to testify, knowing he would invoke a Fifth Amendment privilege against self incrimination. The State called Walter Banks to testify. He refused, claiming the Fifth Amendment. During an in camera hearing, Walter Banks reiterated his stance. The trial court informed him that he had no valid Fifth Amendment privilege, and could not refuse to testify. The State then requested that it be allowed to call him to "refresh his recollection" with his prior statement. Banks objected. After hearing argument, the trial court overruled the objection and allowed the State to do so. On direct examination, the State asked Walter Banks ten (10) questions. In response to each one, Walter Banks invoked the Fifth Amendment. The trial court was correct. Walter Banks had no valid Fifth Amendment privilege to invoke, as it only protects individuals from self-incrimination. 12 Here, Walter Banks instead was being called to incriminate his brother. HN3Go to the description of this Headnote."Regardless of the validity of the claim of privilege, the law requires that the claim [of privilege] be asserted outside the jury's presence, 'to the extent practicable.'" 13 The trial court knew that Walter Banks would refuse to testify, and would invoke a privilege, but still allowed the State to call Walter Banks before the jury. The State then asked Walter if he knew who killed Sun Travis, and if his brother had told him that he killed Sun Travis. This should not have occurred.

12 Jackson v. State, 1998 OK CR 39, 964 P.2d 875, 886, cert. denied, 526 U.S. 1008, 119 S. Ct. 1150, 143 L. Ed. 2d 217 (1999). 13 Id., quoting 12 O.S. 1991, § 2513(B).

However, allowing Walter Banks to be questioned before the jury is only reversible error if (1) the State crafted its case around inferences arising from privilege invocation or (2) "the witness's refusal to answer questions added critical weight to the State's case in a form not subject to cross-examination." 14 The only logical inference from the State/Walter Banks exchange is that Walter knew the answer to both questions and that it was his brother, defendant Anthony Banks, who killed Sun Travis. However, the State did not build its case on this inference nor did it add critical weight thereto.

14 Johnson v. State, 1995 OK CR 43, 905 P.2d 818, 822.

The State's case was built on DNA evidence and the defendant's own statement. The State never mentioned Walter's refusal to testify again--not even in closing. 15 Banks admitted his presence at the victim's abduction, rape, and murder. His statements were corroborated and his participation established by DNA found in and on the victim. We conclude that any error in allowing Walter Banks to be questioned after he attempted to invoke the Fifth Amendment privilege was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt because it did not contribute to the jury's verdict.

15 In closing, the State did refer to the "Walter Banks theory" but this was not a comment on his failure to testify. Instead, it was a comment on Banks's assertion that his brother Walter could have been the perpetrator.

In Proposition IV, Banks complains that his trial was rendered fundamentally unfair by the State's introduction of other crimes evidence--specifically, three references during opening and closing arguments to Banks's reason for talking to police about the Travis murder. The prosecutor told the jury that Banks had given his statement to get "out of trouble," to get "a break," and to get "some help from the police." 16 None of these comments informed the jury that Banks had committed any other crimes, and the mere suggestion that he may have is not improper. The prosecutor's arguments were fair comments on Banks's motivation for giving his statement to the police. This proposition is denied.

16 Banks did not object to any of the comments. 17 Bernay v. State, 1999 OK CR 46, 989 P.2d 998, 1008, cert denied, 531 U.S. 834, 121 S. Ct. 92, 148 L. Ed. 2d 52 (2000). (mere suggestion of other crimes does not trigger rules regarding their admissibility).

In Proposition X, Banks argues that the trial court erred in failing to give separate verdict forms for felony murder and malice aforethought murder. Although this is the better practice, it is not constitutionally required. 18 Since the evidence supported Banks's conviction for both felony and malice aforethought murder, the verdict was proper. 19 This proposition is denied.

18 Schad v. Arizona, 501 U.S. 624, 645, 111 S. Ct. 2491, 2504, 115 L. Ed. 2d 555 (1991)(U.S. Constitution does not command use of separate verdict forms on alternative theories of first degree murder). 19 Hain v. State, 1993 OK CR 22, 852 P.2d 744, 752, cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1020, 114 S. Ct. 1402, 128 L. Ed. 2d 75 (1994). (single verdict form proper where evidence supports malice aforethought or felony murder).

ISSUES RELATING TO SECOND STAGE PROCEEDINGS

In Proposition IV, Banks argues that the trial court erred in overruling his objection to the title, but not contents, of one of the prosecutor's illustrations entitled "Trail of Terror" which detailed Banks's criminal history. The trial court overruled the objection by finding that the title reasonably commented on the evidence and was not unduly prejudicial. Although the illustration was neither admitted into evidence nor included in the record, we review Banks's argument based upon the existing record. Banks claims that the "Trail of Terror" title was prejudicial and inflammatory. He nevertheless concedes that had the illustration merely included the summary of Banks's past convictions, without the title, it would have been an admissible statement for sentencing purposes. We fail to see how this three-word title was unduly prejudicial, as it fairly commented on Banks's lengthy criminal history. 20 This Proposition is denied.

20 Le v. State, 1997 OK CR 55, 947 P.2d 535, 554, cert. denied, 524 U.S. 930, 118 S.Ct. 2329, 141 L. Ed. 2d 702 (1998).

In Proposition IX, Banks claims that his death sentence must be overturned because the jury was allowed to sentence him to death without determining his culpability for felony murder. HN5Go to the description of this Headnote.To be so sentenced, at minimum Banks had to have participated in the underlying felonies and displayed reckless indifference to human life. 21 Banks's jury made this finding because it was instructed that it could not impose the death penalty without finding beyond a reasonable doubt that Banks either: "1) killed a person, 2) attempted to kill a person, 3) intended a killing take place, 4) intended the use of deadly force, or 5) was a major participant in the felony committed and was recklessly indifferent to human life." 22 Moreover, an appellate court may also make this finding. 23

21 Tison v. Arizona, 481 U.S. 137, 158, 107 S. Ct. 1676, 1688, 95 L. Ed. 2d 127 (1987). 22 O.R. 472. 23 Cabana v. Bullock, 474 U.S. 376, 392, 106 S. Ct. 689, 700, 88 L. Ed. 2d 704 (1986), overruled in part on other grounds by Pope v. Illinois, 481 U.S. 497, 107 S.Ct. 1918, 95 L. Ed. 2d 439 (1987).

The evidence established that the State met the minimum two-part test. Banks participated in Sun Travis's abduction and rape, and transported her to the murder scene. While it remains unclear who actually shot Travis, it is very clear that either Nelson or Banks did, and just as likely to have been Banks as the person he self-servingly named as the perpetrator. Moreover, even if it was not Banks, he intended Travis's death to conceal his participation in her rape. We find that Banks was a major participant in Travis's kidnapping and rape and at a minimum intended her death. Accordingly we find no error. 24 This Proposition is denied.

24 Banks also argue in Propositions X and XI that since the jury did not and could not have made an individualized culpability finding, his death sentence was unconstitutional. We disagree and deny those arguments for the reasons stated in this Proposition.

In Proposition XIII, Banks claims that the trial court erred in overruling his Motion to Strike the Previous Felony Aggravating Circumstance as Void or alternatively, grant him a Brewer hearing. 25 Banks specifically argues that error occurred when the State presented the facts of Banks's prior conviction for an unrelated first degree murder charge without a Brewer hearing. These arguments fail.

25 Brewer v. State, 1982 OK CR 128, 650 P.2d 54, 63, cert. denied, 459 U.S. 1150, 103 S. Ct. 794, 74 L. Ed. 2d 999 (1983). (defendant allowed to stipulate to prior violent felonies). First, we see no reason to change our prior ruling finding the previous violent felony aggravating circumstance constitutional. 26 In any event, Banks was not entitled to a Brewer hearing regarding his previous first degree murder conviction; its underlying facts were properly introduced to support the continuing threat aggravating circumstance.

26 Cleary v. State, 1997 OK CR 35, 942 P.2d 736, 746-47, cert. denied, 523 U.S. 1079, 118 S. Ct. 1528, 140 L. Ed. 2d 679 (1998).

In its Amended Bill of Particulars, the State asserted four aggravating circumstances including the continuing threat and previous violent felony aggravating circumstances. The State also notified Banks that his convictions for two counts of Robbery with a Dangerous Weapon would be used to support the previous violent felony aggravating circumstance. Pursuant to Brewer, Banks stipulated that these convictions were for violent felonies. Banks's other felony convictions, including his first degree murder conviction, were used to support the continuing threat aggravating circumstance. Banks asserts that he should also have been allowed to stipulate to his first degree murder conviction to prohibit the State from introducing its underlying facts into evidence. This claim lacks merit as Banks's prior first degree murder conviction was not used to support the previous violent felony aggravating circumstance. Even had it been, the State could have presented its underlying facts to support the continuing threat aggravator. 27 This Proposition is denied.

27 Smith v. State, 1991 OK CR 100, 819 P.2d 270, 277-78, cert. denied, 504 U.S. 959, 112 S.Ct. 2312, 119 L. Ed. 2d 232 (1992). (HN6Go to the description of this Headnote.when state alleges prior violent felony and continuing threat aggravating circumstances, it may introduce evidence of factual basis for stipulated felony convictions to support continuing threat aggravating circumstance).

In Proposition XIV, Banks argues that the evidence was insufficient to support the aggravating circumstance that the Travis murder was committed to avoid or prevent lawful arrest or prosecution. HN7Go to the description of this Headnote.We review the evidence of this aggravator for proof of a predicate crime, separate from the murder, for which the defendant is attempting to avoid prosecution. 28 Consideration is given to the circumstantial evidence to determine if "any reasonable hypothesis exists other than the defendant's intent to commit the predicate crime." 29

28 Romano v. State, 1995 OK CR 74, 909 P.2d 92, 119 cert. denied, 519 U.S. 855, 117 S. Ct. 151, 136 L. Ed. 2d 96 (1996). 29 Id.

Here, the evidence indicated that Travis was raped and kidnapped, that both Banks and Nelson committed these crimes, and at least intended her death. 30 Further, the only reasonable hypothesis for Travis's murder was that it was done to prevent her from identifying her assailants and instigating their arrest or prosecution for kidnapping and rape. The evidence was sufficient, and this Proposition is denied.

30 See Propositions I and IX. In Proposition XV, Banks alleges that the trial court erred in overruling his Motion to Strike the "heinous, atrocious and cruel" aggravating circumstance for insufficient evidence, and that the trial evidence failed to support the jury's finding that it existed. HN8Go to the description of this Headnote.We review the evidence presented at trial in a light most favorable to the State to determine if the victim's death was preceded by conscious serious physical abuse or torture. 31

31 Romano, 909 P.2d at 118.

The trial judge correctly overruled the motion and determined that the evidence was sufficient. While conscious, and before her execution, Sun Travis was kidnapped, physically assaulted, and raped and sodomized by Banks and Nelson. 32 Her ordeal lasted over two hours. Such evidence was sufficient to prove extreme mental and physical suffering and constituted serious physical abuse and torture. Thus, we find that the evidence supported the jury's finding of the "heinous, atrocious and cruel" aggravating circumstance. This Proposition is denied.

32 Banks continues to assert, as he did in the preceding Propositions, that the evidence did not show that he participated in the acts preceding Travis's death or her death. However, as we have stated, the evidence established that Banks and Nelson committed Travis's kidnapping, rape and murder. In Proposition XI, Banks claims that the trial court erred in denying his Motion to Quash Bill of Particulars and Declare the Death Penalty Unconstitutional. Banks specifically asserts that the death penalty is unconstitutional because a bill of particulars is filed solely at the prosecutor's discretion without a finding of probable cause. In previously rejecting this argument, this Court found that the combination of the Oklahoma statutes and case law provide adequate guidelines to direct the prosecutor in deciding whether to pursue the death penalty. 33 This Proposition is denied. 33 Romano v. State, 1993 OK CR 8, 847 P.2d 368, 393, cert. granted in part by Romano v. Oklahoma, 510 U.S. 943, 114 S. Ct. 380, 126 L. Ed. 2d 330 (1993).

In Proposition XII, Banks ask this Court to reconsider its previous ruling upholding the constitutionality of Oklahoma's death penalty scheme and its previous decision finding that the sentencing procedure does not offend the Oklahoma Constitution because it requires a jury to make special findings of fact. Banks offers no compelling justification for our doing so, either in his brief or in his motions filed in the trial court. Thus, we find no reason to overrule our previous decisions. 34 34 Id. 847 P.2d at 384-85 (verdicts rendered in capital sentencing procedure are general verdicts complying with Art. 7, § 15 of the

Oklahoma Constitution); and Hain v. State, 852 P.2d 744, 747-48 (Okl.Cr.1993), cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1020, 114 S. Ct. 1402, 128 L. Ed. 2d 75 (1994). (Oklahoma capital punishment system constitutional and meets established Supreme Court requirements).