30th murderer executed in U.S. in 2006

1034th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

16th murderer executed in Texas in 2006

371st murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

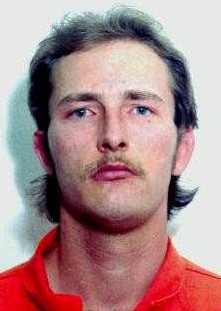

Robert James Anderson W / M / 26 - 40 |

Audra Ann Reeves W / F / 5 |

Summary:

One afternoon, 5 year old Audra Reeves went outside to play. As she returned home past Anderson's home, he abducted her and took her inside, where he attempted to rape her, then choked, stabbed, beat and drowned her. He then stuffed her body into a large foam cooler, pushed the cooler along the street in a grocery cart and dumped it in a trash bin, where it was discovered. Upon arrest, Anderson gave a complete confession.

Citations:

Anderson v. State, 932 S.W.2d 502(Tex.Cr.App. 1996) (Direct Appeal)

Final Meal:

Lasagna, mashed potatoes with gravy, beets, green beans, fried okra, two pints of mint chocolate chip ice cream, a fruit pie, tea and lemonade.

Final Words:

"I am sorry for the pain I have caused you. I have regretted this for a long time. I am sorry." Anderson also apologized to his family.

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Robert Anderson)

Inmate: Anderson, Robert JamesDate of Birth: 5/29/66

TDCJ#: 999084

Date Received: 12/27/93

Education: 12 years

Occupation: security officer

Date of Offense: 6/9/92

Native County: Great Lakes, Illinois

Race: White

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Brown

Eye Color: Blue

Height: 6 ft 02 in

Weight: 149

Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Texas Attorney General Media Advisory

MEDIA ADVISORY - Monday, July 17, 2006 - Robert James Anderson Scheduled For ExecutionAUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about Robert James Anderson, who is scheduled for execution after 6 p.m. Thursday, July 20, 2006. In 1993, Anderson was sentenced to death for the capital murder of 5-year-old Audra Ann Reeves of Amarillo.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

On June 9, 1992, Audra Reeves went outside to play. Robert James Anderson abducted Reeves as she was passing his residence and took her inside, where he attempted to rape her, then choked, stabbed, beat and drowned her. In the early afternoon of the same day, several witnesses reported seeing Anderson pushing a grocery cart up the street with a white ice chest inside. One witness reported seeing Anderson near a dumpster in an alley. One of the witnesses found the ice chest containing Audra’s body in the dumpster. The witness gave a description of Anderson to the police. Anderson was arrested later in the day after he was identified as the individual who pushed the grocery cart. Anderson gave police a written statement in which he admitted to killing Audra and stuffing her body in a white ice chest and dumping the chest in a dumpster. Anderson’s confession was corroborated by other evidence at trial.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

A Potter County grand jury indicted Anderson for the capital murder of Audra Reeves. On November 10, 1993, a jury found Anderson guilty of capital murder. The same jury sentenced him to death on November 15, 1993.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Anderson’s conviction and sentence on September 11, 1996. The U.S. Supreme Court on June 27, 1997, denied Anderson’s petition for writ of certiorari. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied Anderson’s state application for writ of habeas corpus on November 17, 1999.

A U.S. district court on March 23, 2004, denied Anderson’s federal writ of habeas corpus. After filing a notice of appeal in the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Anderson, sought to waive all further federal appeals. His appellate counsel filed a motion asking the Fifth Circuit to stay all proceedings in that court and remand the case to the U.S. district court for the limited purpose of having Anderson psychologically evaluated to determine his competency to waive his appeals. The 5th Circuit Court granted Anderson’s motion and returned his case to the federal district court on July 20, 2004, to determine his mental capacity to terminate further federal habeas corpus proceedings on his behalf and seek an execution date. Anderson was evaluated on September 13, 2004, and found to be competent, and on December 7, 2004, the district court ruled that Anderson was mentally competent to make the decision to waive his appeals and to instruct his counsel to dismiss any pending federal habeas corpus appeals. On February 10, 2005, Anderson filed a motion to dismiss his appeal in the 5th Circuit Court. The court granted the motion on February 17, 2005.

PRIOR CRIMINAL HISTORY

Anderson does not have any prior convictions. However, the State presented an overwhelming amount of evidence of Anderson’s long-standing obsession with and abuse of young girls, and other antisocial acts. •

Anderson wrote a letter to another inmate admitting his long-standing desire for young girls and that he had taken his anger and desire out on the victim in this case.

• Anderson’s older biological sister, testified that Anderson had been sent to the Methodist Children’s Home and later hospitalized for his obsession with young girls.

• Anderson’s eleven year-old niece, Charity Anderson, testified that Anderson had lived with her family for several months beginning in January, 1992. Anderson often babysat Charity, her six-year-old brother Jeremiah, and her eight-year-old sister Raven. Anderson often stared at Charity and frequently invited Raven to sit on his lap. On one occasion, Anderson picked up Jeremiah by the throat and held him for several minutes. Anderson told the boy’s parents that Jeremiah had hurt his neck with a stick.

• Rebekah Anderson, Anderson’s stepsister, testified that, when she was five years old, she was sitting on Anderson’s lap. Anderson unzipped his pants and took off Rebekah’s shorts. Their parents interrupted them before Anderson could proceed any further. When Rebekah was three, her sister, Delores Davis, witnessed Anderson with his hand beneath Rebekah’s skirt while she sat on his lap.

• Myra Jean Anderson, Anderson’s biological sister, testified that Anderson began sexually assaulting her when she was seven years old. At first, Anderson had Myra fondle him, but around the age of nine or ten years, Anderson began forcing her to engage in oral sex. When Myra was thirteen, Anderson tried to have intercourse with her, but they were caught by their parents. Anderson was also physically abusive: when Myra was seven, Anderson broke off the chain guard on her bicycle, then pushed her down a hill, causing her to fall and severely cut her leg. Also, Anderson held Myra down and repeatedly hit her on her knees with a baseball bat.

• Helena Cristina Garza, Anderson’s stepsister, testified that Anderson began fondling her when she was six years old. As Helena got older, Anderson forced her to fondle him. At the age of ten, Anderson forced her to have intercourse and continued to do so about once a week, for approximately one year. Anderson also forced Helena to perform oral sex. To gain Helena’s cooperation, Anderson struck her or threatened her with a baseball bat. When Helena was fifteen or sixteen years old, Anderson took her for a ride on his motorcycle. Once in a secluded area, Anderson raped Helena.

• Carla Rene Burch, a friend of Myra, spent the night at the Anderson home when she was twelve years old. She was awakened in the middle of the night by something touching her face. Anderson was standing in front of her with only a towel wrapped around him. Anderson had pulled the blanket off Carla and raised her nightgown; he asked her to accompany him to his room. Carla refused but Anderson persisted until Carla tried to awaken Myra.

• Anderson’s former wife, Debbie Kay Anderson – who was described as mentally handicapped with an IQ of 69 — testified that Anderson was physically abusive towards her. Debbie was seen with extensive bruising on her shoulders, arms, and face. Anderson often padlocked Debbie in their apartment when he left.

• Anderson attempted to sexually assault a two-year-old girl his wife Debbie was babysitting. Debbie heard the girl crying and walked into a room to discover that Anderson had taken off the girl’s diaper and pulled down his pants. Anderson grabbed Debbie and began choking and hitting her, telling her not to tell anyone.

• Debbie also described how Anderson frequently drove to the park and watched children or watched children from the apartment. Anderson would then go in their bathroom and masturbate.

• A forensic psychiatrist who testified for the defense diagnosed Anderson as a pedophile (the preferred choice of children as sexual partners), with some trends toward sexual sadism.

"Killer of 5-year-old in Texas executed," by Michael Graczyk. (Associated Press July 20, 2006, 7:03PM)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas — A child sex offender apologized in a voice choking with emotion before he was executed Thursday for abducting and killing a 5-year-old girl in Amarillo 14 years ago. "I am sorry for the pain I have caused you," Robert Anderson told the grandmother of his victim. "I have regretted this for a long time. I am sorry." "Anderson also apologized to his family. As the lethal drugs began taking effect, Anderson muttered a prayer. Eight minutes later at 6:19 p.m., he was pronounced dead.

Anderson, 40, had acknowledged the horrific slaying of Audra Reeves and asked that no new appeals be filed to try to block his execution, the 16th this year in Texas and the second in as many days.

According to court records and Anderson's confession, he forced the girl to accompany him into the house and tried to rape her, then choked her and beat her with a footstool. When he discovered she still was alive, he drowned her in a bathtub. He stuffed her body into a large foam cooler, pushed the cooler along the street in a grocery cart and dumped it in a trash bin.

Anderson had a history of sexual offenses involving children that dated to his teen years in Tulsa, Okla., and said he'd been in and out of centers to deal with his obsession with young girls.

"Grandma hopes to find closure," by Michael Smith. (Web-posted Thursday, July 20, 2006)

Every time Grace Lawson sees a little girl with blonde hair, images of her granddaughter, Audra Reeves, come to her mind. The images usually are of Audra doing one of her favorite things - picking flowers - and giving them to the ones she loved, like Lawson and her father, Clarence Reeves Jr. "She'd bring them to me and her dad and say, 'Aren't they pretty? Aren't they pretty?'" Lawson said Tuesday from her home in Brownwood. "She was just happy always had a little smile, she was just a beautiful little girl."

Thoughts of the last time Lawson saw Audra, however, bring on darker feelings. "I felt guilty because they had come through here and she wanted to stay with me, and I said, 'No, you go on and visit with daddy,'" Lawson said. "And she was up there exactly one week" when she was brutally killed. Audra's life ended after she bore the callous brunt of Robert James Anderson's brutal, savage fury in June 1992. Anderson admitted to ravaging the 5-year-old girl in his Amarillo home. He abducted her as she walked home from a San Jacinto park. He sexually assaulted her, beat her with a pipe, a stool and his hand, stabbed her with a paring knife and a barbecue fork despite the little girl's pleas for mercy and then drowned her. Anderson was convicted and sentenced to death for Audra's murder and is scheduled to face lethal injection as punishment at 6 p.m. today in Huntsville. Lawson said she will drive to Huntsville this morning to watch Anderson get his due and hopefully begin to close the trying 14-year wait for justice to be served. "I'm not a violent person at all, but I am looking forward to this closure knowing that he is going to die for what he did," she said. The family has had to endure the trial - during and after which Lawson said she "couldn't eat or sleep for a while because of it" - and years of state and federal court appeals, which always jolted them back to the gruesome details of Audra's death.

Lawson said she always had the nagging worry that as long as Anderson was alive, other children were in danger. "We had him, but there was still the possibility that he could escape or what have you, and if he did this to another child it would have killed us," she said.

Anderson not only stilled Audra's voice but obliterated the family, Lawson said. Audra's father thinks about the details of her death constantly and was determined to "get to" Anderson any way he could. The thoughts, she said, led him down a spiral of alcoholism and driving while intoxicated convictions, and he is now serving time in prison. Audra's mother also has served time in prison for stabbing someone, Lawson said. Memories of the summer of 1992 still tears up everyone too much to dwell on, which is why Lawson said she hopes Anderson's execution will open a new chapter for the family.

Lawson admits that she hasn't forgiven Anderson and probably never will. And if the closure she hopes for doesn't come when Anderson expires tonight, Lawson said she plans to do a lot of praying. "I have like a weight," Lawson said. "It feels like you're heavy inside and I'm hoping it will disappear, and that I'll feel lighter, like there's not a load on me."

"Child killer waives appeals, set to be executed Thursday," by Michael Smith. (07/18/06)

Nightmares of little Audra Reeves' face so plagued Robert James Anderson that he told a federal judge during a 2004 hearing that he wanted to waive all of his appeals and be executed. The state is on schedule to grant Anderson's wish at 6 p.m. Thursday in Huntsville, when he will be executed for the brutal June 9, 1992, slaying of 5-year-old Reeves. So far, as he said he wouldn't, Anderson has not filed any federal appeals to block his execution. "We don't anticipate any filings at this point," said Tom Kelley, a spokesman with the Texas Attorney General's Office.

Anderson, now 40, admitted to Amarillo police to abducting Reeves as she walked home from a nearby park after Anderson had an argument with his ex-wife, according to court records. Anderson sexually assaulted the girl, choked her, beat her with his hand and several objects then drowned her after telling her to wash off her blood. He then stuffed Reeves' body in a Styrofoam cooler and dumped the cooler in a Dumpster in the 400 block of South Tennessee Street. He was arrested when a neighbor identified him as the man seen pushing the cooler through the area in a grocery cart.

A Potter County jury convicted Anderson and sentenced him to death in 1993. Anderson then journeyed through the state and federal appeals processes and met roadblocks at each juncture.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Anderson's conviction in 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review his case in 1997 and the state criminal appeals court again denied Anderson's request for a retrial in 1999. In 2004, Anderson sought to waive all further federal appeals. After Anderson was deemed mentally competent to waive his appeals, he dismissed his appeal with the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2005.

Anderson will be the 16th offender to be executed this year in Texas and the seventh executed offender from Potter County since capital punishment was reinstated in 1976, according to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice records.

"Killer of 5-year-old in Amarillo volunteering to die Thursday," by Michael Graczyk. (AP 07/20/06)

Child sex offender Robert Anderson voluntarily headed to the Texas death chamber Thursday evening for abducting and killing a 5-year-old girl in Amarillo 14 years ago. Anderson acknowledged the horrific slaying of Audra Reeves and asked that no new appeals be filed to try to block his execution, the 16th this year in Texas and the second in as many days.

"The only way I want this stopped is if they give a moratorium to the death penalty," Anderson, 40, said in a recent death row interview where he took sole responsibility for the girl's murder. "There was nobody else, just me," he said. "She was totally an innocent victim."

Anderson had a history of sexual offenses involving children that began as a teenager in Tulsa, Okla., and said he'd been in and out of centers "for deviant behavior," as he described them, to deal with his obsession for young girls. "My whole life is a regret," he said, adding that he looked forward to dying. "I should have been in prison when I was 15."

Audra lived with her mother in Florida and had just arrived in Amarillo days earlier to spend the summer with her father. She was playing outside on June 9, 1992, when Anderson snatched her as she walked by his Amarillo home. "It was a messed-up day," Anderson said. "A lot of things went wrong." An argument earlier that day with his wife of about eight months set him off, he said. "The whole day revolved around the fight," he said. "She stormed out of the house and said when she returned she didn't want to find me."

According to court records and Anderson's confession, he forced the girl to accompany him into the house and tried to rape her, then choked her and beat her with a footstool. When he discovered she still was alive, he drowned her in a bathtub. He stuffed her body into a large foam cooler, pushed the cooler down the street in a grocery cart and dumped it in a trash bin. Anderson was apprehended a few blocks away as he was walking back toward home. A neighbor had discovered the body in the cooler and identified him as the man seen wheeling the shopping cart toward the garbage container. Detectives searching his home found a piece of the girl's hair barrette in a bathroom trash can. The other piece was in the ice chest.

An Amarillo jury took less than 15 minutes to return a guilty verdict and less than 30 minutes to determine Anderson should die. "By far, it was absolutely the worst thing a little girl could ever go through," Chuck Slaughter, the Potter County assistant district attorney who prosecuted Anderson, said this week. "If there's anybody out there who deserves the punishment he received from a jury, it would be Robert Anderson."

Anderson was found to be mentally competent despite having visions of what he said were angels, demons and repeated visits to his cell by his young victim on the anniversary of her death. "She showed up this year and smiled at me and told me I was coming home," he said. "That was really weird."

In 1998, Anderson survived an attack by a fellow death row inmate who stabbed him 67 times with a shank. Anderson said the attack was the result of race-related prison gang extortion efforts and not related to his crime.

On June 9, 1992, neighbors observed a man pushing a grocery cart with a styrofoam ice chest inside. Minutes later, one of the neighbors, Lewis Martin, found the ice chest in a dumpster and discovered that the ice chest contained the body of a five-year-old girl. Martin called the police, and an officer was dispatched to look for the suspect. The initial description of the suspect was that of a white male, about thirty years of age, wearing a black shirt, dark jeans, tennis shoes, and an orange baseball cap. Within ten minutes after receiving the dispatch, the officer approached Anderson, who matched the description except for the shirt. The officer asked Anderson for identification and a residential address, both of which Anderson provided.

Anderson asked why he had been stopped, and the officer replied that he was investigating an incident that occurred a few blocks away. The officer then asked Anderson where he was going and where he had been. Anderson answered that he had pushed a grocery cart back to the Homeland store on nearby Western street. At this point, the police officer asked Anderson not to say anything else and further asked Anderson if he would be willing to go back to the scene of that incident so that the witnesses could take a look at him. Anderson agreed to go, but the officer testified that he would have detained him for that purpose had he refused. Anderson sat in the back seat of the patrol car and was driven to the witnesses' location. The witnesses identified Anderson as the individual seen pushing the grocery cart containing a styrofoam ice chest. At that point, Anderson was handcuffed, advised of his constitutional rights, and transported to the Special Crimes Unit.

Upon arrival at the Special Crimes Unit, physical samples were taken from Anderson with his consent. He was also interrogated and gave both oral and written confessions, detailing how he kidnapped, sexually assaulted, choked and gagged, stabbed, beat and drowned the girl. He said he kidnapped Audra from in front of his home as she returned from playing with other children at a park. He took her inside and tried to rape her. He then beat and stabbed her. Anderson told investigators that after the brutal assault, he stuffed the girl into the cooler, but she tried to crawl out. He persuaded her to take a bath to clean the blood off her battered body. He then drowned her.

"It's scary sometimes, you know. If I was to be found innocent, it would happen again," Anderson wrote. In 2004, Anderson told a federal judge that he wanted to abandon further appeals and be executed. Anderson said he didn't want to "hurt anybody any longer" and that he believed God forgave him for abducting, sexually assaulting and killing Audra Ann Reeves. In his recommendation in 2004 to deny Anderson's initial federal appeal, US Magistrate Clinton Averitte cited the "particularly egregious" nature of the crime. "His persistence in carrying out this assault and murder over a period of at least 45 minutes, leaving no major part of her body that did not sustain wounds, and undaunted by a plea for mercy, would support a finding of sufficient aggravation, in and of itself, to support imposition of the death penalty," Averitte wrote. The appeal was denied.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Robert James Anderson, 40, was executed by lethal injection on 20 July 2006 in Huntsville, Texas for the kidnapping, sexual assault, and murder of a 5-year-old girl.

On 9 June 1992, Audra Reeves was walking home from an Amarillo park. As she passed in front of Anderson's house, Anderson, then 26, abducted her and took her inside. After attempting to rape her, Anderson choked her, beat her with a stool, and stabbed her with a paring knife and a barbecue fork. Anderson then took the girl into the bathroom and drowned her in the bathtub. He then placed her body in a foam ice chest and, using a grocery cart to transport it, left it in a dumpster behind another residence. The ice chest containing the girl's nude body was found in the dumpster by a homeowner throwing out his trash.

The person who found the body also witnessed Anderson near the dumpster earlier. Other witnesses reported seeing Anderson pushing a grocery cart along the street, carrying a white ice chest. The witnesses gave a description of the suspect to police, and Anderson was arrested as he was walking back home. Anderson gave a written confession in which he admitted kidnapping and killing Audra. He said he had recently had an argument with his wife.

Anderson had no prior criminal arrests, but ample evidence was presented at his punishment hearing of his previous sexual assaults on young girls and his violent nature.

His stepsister, Rebekah Anderson, testified that when she was five years old, Anderson had her sit on his lap, then he unzipped his pants and removed her shorts. Rebekah's sister, Delores Davis, testified that when Rebekah was three, she saw Anderson with his hand beneath Rebekah's skirt as she sat on his lap. Anderson's 11-year-old niece, Charity Anderson, testified that about six months before the murder, Anderson babysat for her and her brother and sister. He frequently invited Charity's 8-year-old sister, Raven, to sit on his lap, and on one occasion, he held her 6-year-old brother, Jeremiah, by the throat for several minutes. Anderson's biological sister, Myra, testified that Anderson sexually assaulted her from age 7 to age 13. He forced her to engage in oral sex and attempted to have intercourse with her. Myra also testified that Anderson pushed her down a hill once, and that he once held her down and hit her repeatedly on her knees with a baseball bat. Another stepsister, Helena Garza, testified that Anderson began fondling her when she was six years old. When she was ten, Anderson forced her to have intercourse and perform oral sex about once a week, for about a year, by striking or threatening her with a baseball bat. Anderson also raped Helena when she was 15 or 16. Myra's friend, Carla Burch, testified that when she was 12, she spent the night at the Anderson home. She was awakened during the night by someone touching her face. Anderson was standing in front of her wearing only a towel. He had pulled the covers off of Carla and raised her nightgown. He asked her to come to his room, but she refused. Anderson's ex-wife, Debbie Kay Anderson, testified that Anderson was physically abusive towards her, and that he often padlocked her in their apartment when he left. Debbie also testified that when she was babysitting a 2-year-old girl, she heard the girl crying and walked into the room to see the girl with her diaper removed and Anderson with his pants down. Anderson then grabbed Debbie and began choking and hitting her, telling her not to tell anyone.

A jury convicted Anderson of capital murder in November 1993 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in September 1996. His subsequent state appeals were denied. In March 2004, a U.S. district court denied his federal writ of habeas corpus. Anderson filed an appeal to the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, but then he decided to waive all further federal appeals. After a psychological evaluation found him competent to waive his appeals, the Fifth Circuit dismissed his appeal in February 2005.

In the competency hearing before U.S. Magistrate Clinton Averitte, Anderson stated that his victim often appeared to him in nightmares. He said that, in prison, he dedicated himself to a Christian way of life, and that God had forgiven him for the killing. "God has granted me peace that I didn't have before," Anderson told Averitte. "I don't want to hurt anybody any longer, and I want to be executed."

In 1998, Anderson was attacked by a fellow death row inmate who stabbed him 67 times with a shank. Anderson said the attack was due to a race-related prison gang extortion effort and was unrelated to his crime.

"My whole life is a regret," Anderson said in a recent interview from death row. "I made bad choices all the way up and down as far back as age ten ... I should have been in prison when I was 15." He said that the day of the killing was "a messed-up day ... a lot of things went wrong." He said that an argument with his wife of about eight months set him off. "She stormed out of the house and said when she returned, she didn't want to find me." He said that at the time of his arrest, "the whole day had slipped me mind ... for about an hour or so, I didn't understand what the cops were asking me. Then suddenly, it just snapped ... everything came flooding back, all at once."

"I'm actually looking forward to dying," Anderson said in the interview. "I've made peace with the Lord and I'm trying to make peace with my family. And I have tried to make apologies with the victim's family over the years, with no responses. I didn't expect them to respond." As his execution date drew near Anderson did not file any of the appeals that condemned prisoners usually file in an effort to have their execution stayed.

Anderson took full responsibility for his crime. "There was nobody else, just me," he said. "She was a totally innocent victim."

"I am sorry for the pain I have caused you," Anderson told the victim's grandmother, Grace Lawson, at his execution. "I have regretted this for a long time. I am sorry. I only ask that you remember the Lord because He remembers us and He forgives us if we ask Him." Anderson also apologized to his own family for "the pain of all the years and for putting you through all the things we had to go through." The lethal injection was then started. As the drugs began taking effect, Anderson prayed. He was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Robert Anderson, TX - July 20, 2006

Do Not Execute Robert Anderson!

Robert Anderson was convicted of kidnapping, raping and murdering five-year-old Audra Anne Reeves in Amarillo on June 9, 1992. Neighbors of Reeves saw a man pushing a grocery cart, which contained a large Styrofoam cooler. Later that day one of the neighbors found the same cooler in a nearby dumpster. Upon opening the chest the man discovered the body of Reeves inside. After giving the description of the man pushing the grocery cart to police, Anderson, who fit the description of the subject, was picked up several blocks away. The neighbor made a positive identification and Anderson was placed under arrest. While under interrogation at the police station Anderson nearly immediately confessed to the murder. Though Anderson had a history of sexual assault and undoubtedly committed the murder for which he was convicted, he does not deserve the sentence of death.

In Texas two things must be determined by the jury to sentence someone to death. First the jury must find that there is a probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society. The second is that the jury must take into consideration the defendant’s character, background and all personal moral culpability and find that there are insufficient mitigating circumstances to warrant a sentence of life imprisonment. The problem in Anderson’s case, in fact in all death penalty cases, lies in the first requirement of the death penalty. Prison serves to take the convicted criminal out of society, to protect society from that person. In Anderson’s trial an expert witness testified that Anderson would not be a threat to anyone in a strictly controlled environment, prison, because he would be kept away from women and children. Though the crimes committed by Robert Anderson were extremely heinous, an incarcerated Robert Anderson does not constitute a threat to general society and should not be put to death.

Please write to Gov. Rick Perry on behalf of Robert Anderson!

Anderson v. State, 932 S.W.2d 502(Tex.Cr.App. 1996) (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted in the 108th District Court, Potter County, Ebelardo Lopez, J., of murder and sentenced to death. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Keller, J., held that: (1) defendant who agreed to accompany officer to witnesses' location was not under arrest; (2) there existed probable cause to believe that defendant had committed murder and was about to escape, justifying warrantless arrest; (3) prosecutor's references to parole did not require submission of instruction on parole eligibility; (4) death penalty has not been arbitrarily imposed due to the many different schemes that have existed since 1989; and (5) assuming that the word “or” in Texas Constitution requires disjunctive reading of the words “cruel” and “unusual,” death penalty is neither. Affirmed. Clinton, J., concurred in the result. Baird, J., filed a concurring opinion. Overstreet, J., filed a dissenting opinion.

KELLER, Judge.

Appellant was convicted of murder during the course of aggravated sexual assault and aggravated kidnapping and sentenced to death. Appeal to this Court is automatic. Art. 37.071(h) Appellant presents twenty-six points of error. We will affirm.

1. Pretrial Investigation

On June 9, 1992, neighbors observed a man pushing a grocery cart with a styrofoam ice chest inside. Minutes later, one of the neighbors, Lewis Martin, found the ice chest in a dumpster and discovered that the ice chest contained the body of a five-year-old girl. Martin called the police, and officer Barry Carden was dispatched to look for the suspect. The initial description of the suspect was that of a white male, about thirty years of age, wearing a black shirt, dark jeans, tennis shoes, and an orange baseball cap.

Within ten minutes after receiving the dispatch, Carden approached appellant, who matched the description except for the shirt. Carden asked appellant for identification and a residential address, both of which appellant provided. Appellant asked why he had been stopped, and Carden replied that he was investigating an incident that occurred a few blocks away. Carden then asked appellant where he was going and where he had been. Appellant answered that he had pushed a grocery cart back to the Homeland store on nearby Western street. At this point, Carden asked appellant not to say anything else and further asked appellant if he would be willing to go back to the scene of that incident so that the witnesses could take a look at him. Appellant agreed to go, but Carden testified that he would have detained him for that purpose had he refused. Appellant sat in the back seat of the patrol car and was driven to the witnesses' location. The witnesses identified appellant as the individual seen pushing the grocery cart containing a styrofoam ice chest. At that point, appellant was handcuffed, advised of his constitutional rights, and transported to the Special Crimes Unit.

Upon arrival at the Special Crimes Unit, physical samples were taken from appellant with his consent. He was also interrogated and gave both oral and written confessions. Miranda warnings were given and consent forms were signed prior to obtaining these statements. The police also obtained appellant's consent, a valid third party consent, and a warrant to search appellant's home. We will now address appellant's federal constitutional arguments concerning these events.FN2

FN2. In point of error twenty-one, appellant alleges that the pretrial identification was the fruit of an illegal arrest in violation of Texas constitutional and statutory provisions. In points of error twenty-two and twenty-three, Appellant alleges, in addition to his federal claims, that the refusal to suppress the pretrial identifications violated various Texas constitutional and statutory provisions. For each of these points, appellant does not explain how the protection offered by the Texas Constitution or statutes differs from that of the United States Constitution. We decline to make appellant's arguments for him. Johnson v. State, 853 S.W.2d 527, 533 (Tex.Crim.App.1992), cert. denied,510 U.S. 852, 114 S.Ct. 154, 126 L.Ed.2d 115 (1993). Point of error twenty-one and the state-law portions of points twenty-two and twenty-three are overruled.

In point of error twenty, appellant argues that the pretrial identifications were the fruits of an illegal arrest in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution. “A person has been ‘seized’ within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment only if, in view of all the circumstances surrounding the incident, a reasonable person would have believed that he was not free to leave.” California v. Hodari D., 499 U.S. 621, 627-628, 111 S.Ct. 1547, 1551, 113 L.Ed.2d 690 (1991). United States v. Mendenhall, 446 U.S. 544, 554, 100 S.Ct. 1870, 1877, 64 L.Ed.2d 497 (1980) (opinion of Stewart, J.). The “reasonable person” standard presupposes an innocent person. Florida v. Bostick, 501 U.S. 429, 438, 111 S.Ct. 2382, 2388, 115 L.Ed.2d 389 (1991) (emphasis in original). Further, an officer's subjective intent to arrest is irrelevant unless that intent is communicated to the suspect. Mendenhall, 446 U.S. at 554 n. 6, 100 S.Ct. at 1877 n. 6. See also Stansbury v. California, 511 U.S. 318, ----, 114 S.Ct. 1526, 1530, 128 L.Ed.2d 293, 300 (1994) (uncommunicated belief that person is a suspect irrelevant to Fifth Amendment custody determination; citing footnote 6 of Mendenhall ).

We have held that a person who voluntarily accompanies investigating police officers to a certain location-knowing that he is a suspect-has not been “seized” for Fourth Amendment purposes. Livingston v. State, 739 S.W.2d 311, 327 (Tex.Crim.App.1987), cert. denied,487 U.S. 1210, 108 S.Ct. 2858, 101 L.Ed.2d 895 (1988). We have also explained that:

We are unaware of any rule of law which forbids lawfully constituted officers of the law from requesting persons to accompany them, or of providing transportation to the police station or some other relevant place in furtherance of an investigation of a crime. Nor are we aware of any rule of law that prohibits police officers from voluntarily taking a person to the police station or some other relevant place in an effort to exonerate such person from complicity in an alleged crime. Nor are we aware of any rule of law which forbids one to reject such a request. If the circumstances show that the transportee is acting only upon the invitation, request, or even urging of the police, and there are no threats, express or implied, that he will be taken forcibly, the accompaniment is voluntary, and such person is not in custody. Dancy v. State, 728 S.W.2d 772, 778 (Tex.Crim.App.), cert. denied,484 U.S. 975, 108 S.Ct. 485, 98 L.Ed.2d 484 (1987). Shiflet v. State, 732 S.W.2d 622, 628 (Tex.Crim.App.1985).

Although Carden would have detained appellant if he had refused to return to the witnesses' location, Carden never communicated this intent. At most, this situation presents a suspect who voluntarily accompanies an officer at the officer's urging to exonerate the suspect of the crime. The only *506 possible objective indication of arrest status was Carden's request that appellant remain silent. We have held, though, that the mere recitation of Miranda warnings does not communicate an officer's intent to arrest. Dancy, 728 S.W.2d at 772. In the present case, the request to remain silent is even less extensive than the standard Miranda warnings. Because appellant was not “seized” prior to the witnesses' identifications, those identifications were not obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment. Point of error twenty is overruled.

******UNPUBLISHED TEXT FOLLOWS******

In points of error twenty-two and twenty-three, appellant argues that the refusal to suppress the pretrial identifications violated the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the United States Constitution. There appear to be three different federal constitutional arguments: (1) that the identifications were made in the absence of counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment, (2) that the identifications were made in the absence of counsel in violation of the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination as applied in Miranda, and (3) that the pretrial identifications were suggestively influenced in violation of due process. The Sixth Amendment right to counsel does not attach until after the commencement of adversary proceedings. United States v. Gouveia, 467 U.S. 180, 187-188, 104 S.Ct. 2292, 2297, 81 L.Ed.2d 146 (1984). Green v. State, 872 S.W.2d 717, 719 (Tex.Crim.App.1994). An arrest, alone, does not constitute the initiation of adversarial judicial proceedings. Green, 872 S.W.2d at 720. As the time of the pretrial identifications, appellant had not even been arrested, much less charged with a crime. Points of error twenty-two and twenty-three are overruled.

The Fifth Amendment “right to counsel” is an offshoot of a person's right against self-incrimination. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966). The United States Supreme Court has held that a suspect lineup (i.e. the mere showing of the suspect to potential witnesses) is not “testimonial” and, therefore, does not implicate the Fifth Amendment “right to counsel.” United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218, 221-222, 87 S.Ct. 1926, 1929-1930, 18 L.Ed.2d 1149 (1967).

As for appellant's due process argument, he merely states that “the law enforcement officers exerted undue influence in obtaining witness identifications, not only in their treatment of appellant, but by the manner that was used to deal with the witnesses.” Appellant does not explain how the manner of dealing with witnesses caused a due process violation nor does he cite any authority for his due process argument. Although appellant refers to witnesses who were allegedly influenced by police officers in a “facts” section of his point of error, he makes no attempt to apply the law to these facts. We will not make appellant's arguments for him. We reject the due process argument as inadequately briefed. Tex. R. App. P. 74(f). Garcia v. State, 887 S.W.2d 862, 871 (Tex.Crim.App.1994).

******END OF UNPUBLISHED TEXT******

In points of error twenty-four and twenty-five, appellant complains about physical samples taken from his person, oral and written confessions, and evidence obtained from his residence. Appellant alleges that the evidence was obtained in violation of the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution, Article I of the Texas Constitution, and Article 38 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. In these points of error, appellant claims only that these items of evidence were the fruit of an illegal arrest. Appellant cites cases relating to the Fourth Amendment and the Texas statutory (Art. 14) requirements for a warrantless arrest. We hold that claims respecting other constitutional or statutory provisions are waived because of inadequate briefing. Rule 74(f). Garcia, 887 S.W.2d at 871. Johnson, 853 S.W.2d at 533.

As explained with regard to point of error twenty, appellant was not under arrest until the officers formally arrested him after the witness identifications. Although arrests inside the home generally require a warrant, arrests outside the home pass muster under the federal Constitution so long as they are supported by probable cause. New York v. Harris, 495 U.S. 14, 110 S.Ct. 1640, 109 L.Ed.2d 13 (1990). Once appellant was positively identified by the witnesses, there existed probable cause to believe that he committed the crime, and the subsequent arrest was proper under the Fourth Amendment.

Texas law requires a warrant for any arrest unless one of the statutory exceptions is met. Dejarnette v. State, 732 S.W.2d 346, 349 (Tex.Crim.App.1987). Although appellant was arrested without a warrant, the police had probable cause to believe that a felony was committed and that appellant was about to escape in accordance with the exception found in Art. 14.04. Such probable cause exists when law enforcement officials identify the perpetrator while pursuing the fresh trail of a crime, and the identification is made in the perpetrator's presence under circumstances which convey to him the authorities' awareness of his involvement. West v. State, 720 S.W.2d 511, 517-518 (Tex.Crim.App.1986)(plurality opinion), cert. denied,481 U.S. 1072, 107 S.Ct. 2470, 95 L.Ed.2d 878 (1987). In the present case, appellant's disposal of the victim's body resulted in pursuit and arrest within, at most, hours. The need to present appellant before witnesses while the incident was fresh in their memory was evident. At the same time, presenting appellant before these witnesses, and positive identification by them, informed appellant that the authorities had probable cause to arrest him. Hence, in conformance with Art. 14.04, there existed probable cause to believe appellant had committed murder and was about to escape.

Because the arrest was legal, the evidence obtained was not the fruit of an illegal arrest. Points of error twenty-four and twenty-five are overruled.

5. Parole Instructions

In points of error one and two, appellant complains about the trial court's refusal to submit a jury instruction stating that, were he given a life sentence, appellant would be ineligible for parole for a minimum of thirty-five calendar years. Appellant claims that the failure to submit such an instruction violates the cruel and unusual punishments prohibition of the Eighth Amendment and the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. We have ruled adversely to appellant's position on both of these claims. Smith v. State, 898 S.W.2d 838 (Tex.Crim.App.1995)(plurality opinion), cert. denied,516 U.S. 843, 116 S.Ct. 131, 133 L.Ed.2d 80 (1995). Broxton v. State, 909 S.W.2d 912, 919 (Tex.Crim.App.1995).

During oral argument, appellant attempted to distinguish Smith ( Broxton had not yet been decided) by arguing that the present case involved references to parole by the prosecutor during closing argument. For example, during closing argument (emphasis added): PROSECUTOR: Don't give him the opportunity to hurt anybody else in society. Don't give him a chance to do anything like this to anybody and whether it be a check writer or a burglar in prison or your children or my children if and when he gets out. DEFENSE: Your Honor, we object to that as a comment on the Board of Pardons and Paroles. COURT: The jury's been instructed. Mr. Hill, you have two minutes left. PROSECUTOR: Thank you, Your Honor. For whatever reason, for whatever reason that may be. Don't let that stay on-can you imagine what you would feel like later? We can talk about compassion for him but can you imagine how each of us would feel if we were ever in a position to find out that this scorpion did it again, whether it be in prison or somewhere else?

We agree that the emphasized portions are improper references to parole. McKay v. State, 707 S.W.2d 23, 38 (Tex.Crim.App.1985), cert. denied,479 U.S. 871, 107 S.Ct. 239, 93 L.Ed.2d 164 (1986). Appellant argues, based upon footnote 22 in Smith that such argument requires the submission of his requested jury instruction.FN3 We disagree. FN3. Footnote 22 of Smithprovides in relevant part: We also recognize that were a prosecutor, in his or her arguments concerning the new special issue, to urge the jury not to give a defendant a life sentence because he would serve a limited number of years in prison, then Simmons [ v. South Carolina, 512 U.S. 154, 114 S.Ct. 2187, 129 L.Ed.2d 133 (1994)] may command that the jury be informed of the minimum prison terms for capital life prisoners.

An accused should not become entitled, because of argument error, to additional written jury instructions unless traditional remedies for argument error are constitutionally inadequate. Ordinarily, an objection to improper argument is required to preserve error. Banda v. State, 890 S.W.2d 42, 62 (Tex.Crim.App.1994). Even if an objection is lodged, appellant must pursue the objection until he receives an adverse ruling. Flores v. State, 871 S.W.2d 714, 722 (Tex.Crim.App.1993), cert. denied,513 U.S. 926, 115 S.Ct. 313, 130 L.Ed.2d 276 (1994). The only exception to these principles occurs if an instruction to disregard would not have cured the harm. Harris v. State, 827 S.W.2d 949, 963 (Tex.Crim.App.1992), cert. denied,506 U.S. 942, 113 S.Ct. 381, 121 L.Ed.2d 292 (1992). We believe that these traditional principles relating to argument error are constitutionally adequate in the present case because a mere reference to parole is cured by an instruction to disregard. Coleman v. State, 881 S.W.2d 344, 358 (Tex.Crim.App.1994). Brown v. State, 769 S.W.2d 565, 567 (Tex.Crim.App.1989). Footnote 22 of Smith is implicated only if the prosecutor conveys incomplete or inaccurate information about how parole is computed. In such a case, an instruction to disregard may not cure the error because the erroneous information has been conveyed, and truthful information may be required to counteract the prosecutor's statements. Such a remedy might be required, upon a defendant's request, as a less drastic remedy in lieu of a mistrial, to adequately protect a defendant's double jeopardy rights. In the present case, however, the prosecutor's statements did not convey any information about how parole might be calculated; so, the reference to parole could have been cured by an instruction to disregard. If appellant wished to preserve error with regard to the prosecutor's reference to parole during argument, appellant should have objected and received an adverse ruling, or if his objection were sustained, he should have requested an instruction to disregard. Appellant was not entitled to an instruction on the operation of parole laws. Points of error one and two are overruled.

In point of error three, appellant contends that the trial court's written instruction concerning parole violated Article IV § 11 of the Texas Constitution. The trial court instructed the jury that: “During your deliberations you will not consider any possible action of the Board of Pardons and Paroles or the Governor.” Appellant did not object to including this instruction. Nevertheless, we have previously upheld this kind of instruction as an appropriate measure to prevent the consideration of parole laws. Williams v. State, 668 S.W.2d 692, 701 (Tex.Crim.App.1983), cert. denied,466 U.S. 954, 104 S.Ct. 2161, 80 L.Ed.2d 545 (1984). Point of error three is overruled.

7. “Penry” Issue

In point of error ten, appellant contends that the statutory “ Penry ” issue is facially unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment because it does not assign a burden of proof. He specifically contends that the issue's silence concerning the burden of proof renders the capital punishment scheme “unstructured” in violation of Furman. We have already held that the Eighth Amendment does not require that the State be assigned the burden of proof on Penry issues. Barnes v. State, 876 S.W.2d 316, 330 (Tex.Crim.App.), cert. denied,513 U.S. 861, 115 S.Ct. 174, 130 L.Ed.2d 110 (1994). Because the Eighth Amendment does not require limitations on a jury's discretion to consider mitigating evidence, see McFarland, 928 S.W.2d 482, 520-521 (Tex.Cr.App.1996) the Constitution does not require a burden of proof to be placed upon anyone. Point of error ten is overruled.

In point of error nine, appellant asserts that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the federal Constitution requires that we conduct a comparative proportionality review of the death worthiness of each defendant sentenced to death, ensuring that the sentence is not disproportionate when compared to other death sentences. Appellant concedes that the United States Supreme Court rejected similar arguments in Pulley v. Harris, 465 U.S. 37, 104 S.Ct. 871, 79 L.Ed.2d 29 (1984), but asserts his arguments are novel because they are raised under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, instead of under the Eighth Amendment, and because of the impact of the recent holding of Honda Motor Company, Ltd. v. Oberg, 512 U.S. 415, 114 S.Ct. 2331, 129 L.Ed.2d 336 (1994).

According to appellant, Honda suggests that the Due Process Clause requires a comparative proportionality review of all judgments. Appellant asserts that “if such appellate review is required by the Due Process Clause in civil cases, it is required a fortiori in death penalty cases.” We disagree. Honda dealt with civil procedures, which by their nature operate under vastly different due process principles than do criminal cases in general and capital punishment cases in particular. See e.g. In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358, 90 S.Ct. 1068, 25 L.Ed.2d 368 (1970) (due process requirements in criminal proceedings) and Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349, 97 S.Ct. 1197, 51 L.Ed.2d 393 (1977)(death is different). Honda does not stand for the proposition that due process requires comparative proportionality reviews of all civil judgments, much less, all criminal judgments; at most it stands for the proposition that due process requires some minimal safeguard ensuring that individual judgments are not excessive or disproportionate. Honda leaves open the form these safeguards might take. Honda held that a comparative proportionality review was required only because Oregon had no alternative means of safeguarding against excessive or disproportionate judgments. 512 U.S. 415, ---- - ----, 114 S.Ct. 2331, 2340-2341, 129 L.Ed.2d 336, 349-350.

The federal Constitution requires more than the minimal safeguard of a comparative proportionality review to ensure the fair imposition of the death penalty. Because death is qualitatively different from any other punishment, the federal Constitution requires the highest degree of reliability in the determination that it is the appropriate punishment. E.g., Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 305, 96 S.Ct. 2978, 2991, 49 L.Ed.2d 944 (1976); Jurek, 428 U.S. at 276, 96 S.Ct. at 2958; Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 92 S.Ct. 2726, 33 L.Ed.2d 346 (1972) (decided in conjunction with Branch v. Texas ). To ensure this reliability, the United States Constitution imposes requirements of proportionality of offense to punishment, of a narrowly defined class of death eligible *509 defendants, and of an opportunity for each juror to consider and give effect to circumstances mitigating against the imposition of the death sentence. See Tuilaepa v. California, 512 U.S. 967, 114 S.Ct. 2630, 129 L.Ed.2d 750 (1994). In short, the due process principles governing the imposition of a sentence of death are distinct and more onerous than those governing the imposition of a civil judgment. Compare Tuilaepa to Honda.

It is for good reason, therefore, that the United States Supreme Court has not held that due process requires a comparative proportionality review of the sentence of death, but instead has held that such a review would be “constitutionally superfluous.” Pulley, 465 U.S. at 49, 104 S.Ct. at 879. See also Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262, 96 S.Ct. 2950, 49 L.Ed.2d 929 (1976)(upholding our capital punishment scheme even without a comparative proportionality review). Appellant's ninth point of error is overruled.

8. Constitutionality of Death Penalty

In points of error twelve and thirteen, appellant argues that the death penalty, as presently administered, is cruel and unusual under both the federal and Texas constitutions. In points of error fourteen and fifteen, he argues that the death penalty has been arbitrarily imposed due to the many different schemes that have existed since 1989.

The facial validity of the Texas scheme under the United States Constitution has been upheld and we have reaffirmed that holding. Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262, 96 S.Ct. 2950, 49 L.Ed.2d 929 (1976), affirming sub nom., Jurek v. State, 522 S.W.2d 934 (Tex.Crim.App.1975). Muniz v. State, 851 S.W.2d 238, 257 (Tex.Crim.App.), cert. denied,510 U.S. 837, 114 S.Ct. 116, 126 L.Ed.2d 82 (1993). See also Green v. State, 912 S.W.2d 189, 196-198 (Tex.Crim.App.1995)(Baird, J. concurring). We reject appellant's contention that mere changes in the law render the capital punishment scheme unconstitutional. It is generally within the legislature's province to change its laws as it sees fit, and the mere fact that a certain area of the law changes frequently does not in itself show a constitutional violation. Moreover, we recognize that the legislature's changes in the capital punishment scheme have in large part been in response to decisions by this Court and the United States Supreme Court. Such responses are entirely appropriate.

Appellant argues that the Texas constitutional provision is broader than the Eighth Amendment because the Texas Constitution proscribes “cruel or unusual punishments,” TEX. CONST. ART. I § 13, instead of “cruel and unusual punishments” as proscribed in the federal Constitution. He points out that the word “and” in the 1845 version of the Texas Constitution was changed to “or” in the 1876 version. He also relies upon the California case of People v. Anderson, 6 Cal.3d 628, 100 Cal.Rptr. 152, 154-158, 493 P.2d 880, 883-887 (1972) for the proposition that the difference in wording indicates that the state constitutional provision is broader than its federal counterpart.

We do not decide whether the state constitutional provision is broader than its counterpart. Assuming that the word “or” requires a disjunctive reading of the words “cruel” and “unusual,” we find that the death penalty is neither. The Texas scheme punishes only certain aggravated categories of murder which society finds especially reprehensible. SeeTexas Penal Code § 19.03. Further, only criminals who pose a continuing threat to society can be given the death penalty. Art. 37.071 § 2(b)(1). Finally, the death penalty requires that a mere party to a crime have some degree of personal culpability for the death. Art. 37.071 § 2(b)(2) (may only be assessed against the trigger person or against a non-trigger person who intended to kill or anticipated that a human life would be taken). Art. 37.0711 § 3(b)(1) (“deliberateness” requirement). We conclude that the death penalty is not “cruel.” See discussion in Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 178-187, 96 S.Ct. 2909, 2927-2932, 49 L.Ed.2d 859 (1976).

We also find that the death penalty is not “unusual.” This Court has never in its history held the death penalty to constitute cruel and unusual punishment under the Texas Constitution. Brock v. State, 556 S.W.2d 309, 311 (Tex.Crim.App.1977), cert. denied,434 U.S. 1051, 98 S.Ct. 904, 54 L.Ed.2d 805 (1978). Livingston v. State, 542 S.W.2d 655, 662 (Tex.Crim.App.1976), cert. denied,431 U.S. 933, 97 S.Ct. 2642, 53 L.Ed.2d 250 (1977). Points of error twelve through fifteen are overruled. The judgment of the trial court is AFFIRMED. CLINTON, J., concurs in the result.

BAIRD, J., concurring. I concur in the resolution of points of error twenty, twenty-four and twenty-five for the reasons stated in Francis v. State, 922 S.W.2d 176, 177 (Tex.Cr.App.1996)(Baird, J., concurring and dissenting). However, I disagree with the majority's treatment of point of error six for the reasons stated in Morris v. State, 940 S.W.2d ---- (Tex.Cr.App. No. 71,799, 1996 WL 514833, delivered this day)(Baird, J., dissenting). Accordingly, I join only the judgment of the Court.

OVERSTREET, Judge, dissenting.

I dissent to the majority's disposition of appellant's points of error one and two where he complains of the trial court's refusal to inform the jury that if sentenced to life he was statutorily required to serve 35 years in prison before becoming eligible to be considered for parole. I believe the failure to adequately inform the sentencing jury may be a due process violation and may cause the Texas death penalty statute to be unconstitutional as applied.

Additionally, I add that this Court through actual knowledge is well aware that some Texas trial courts do in fact inform some sentencing juries as to what a capital life sentence means. See, e.g., Ford v. State, 919 S.W.2d 107, 116 (Tex.Cr.App.1996); and McDuff v. State, No. 71,872 (Tex.Cr.App., currently pending). This Court has never said that such practice is forbidden, and in fact has noted that there is no express constitutional or statutory prohibition against including such an instruction. Walbey v. State, 926 S.W.2d 307, 313 (Tex.Cr.App.1996).

Some juries who are informed of the parole eligibility law do indeed answer the special issues and return verdicts which result in a death sentence. See, e.g., Ford, supra, McDuff, supra, and Walbey, supra. Other juries which are kept in the dark and not informed about such have returned verdicts which result in a life sentence. See, e.g., Weatherred v. State, 833 S.W.2d 341 (Tex.App.-Beaumont 1992, pet. ref'd); Cisneros v. State, 915 S.W.2d 217 (Tex.App.-Corpus Christi 1996, pet. pending); Norton v. State, 930 S.W.2d 101 (Tex.App.-Amarillo 1996, pet. ref'd). Others which have been informed of the parole eligibility law have returned verdicts which result in a life sentence. See, e.g., Johnson v. State, No. 13-93-504-CR (Tex.App.-Corpus Christi, delivered February 29, 1996), pet. summarily granted and remanded, Johnson v. State, No. 684-96 (Tex.Cr.App. delivered ____________, 1996); Koslow v. State, No. 02-94-385-CR (Tex.App.-Fort Worth, currently pending). And in a myriad of cases in which jurors have been kept in the dark about parole eligibility juries have returned verdicts which result in a sentence of death. See, e.g., Smith v. State, 898 S.W.2d 838 (Tex.Cr.App.1995), cert. denied,516 U.S. 843, 116 S.Ct. 131, 133 L.Ed.2d 80 (1995); Willingham v. State, 897 S.W.2d 351 (Tex.Cr.App.1995); cert. denied,516 U.S. 946, 116 S.Ct. 385, 133 L.Ed.2d 307 (1995); Broxton v. State, 909 S.W.2d 912 (Tex.Cr.App.1995); Rhoades, supra; Martinez v. State, 924 S.W.2d 693 (Tex.Cr.App.1996); Sonnier v. State, 913 S.W.2d 511 (Tex.Cr.App.1995).

Consequently the “luck of the draw” determines whether a defendant's sentencing jury in a capital murder prosecution will be adequately truthfully fully informed or have vital information withheld. Such practice in my opinion gives rise to questions of equal protection of the law under both the Federal and Texas Constitutions, especially when, as shown above, some juries which have been informed as to the proper legal definition of a capital murder life sentence have answered the special issues in a way that mandates life while other juries which have not been so informed have answered the special issues in a way that mandates death. For these reasons I urge this Court to allow the capital sentencing jury to have the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. I truly believe in the trial by jury system and that if capital sentencing juries are given the complete truth regarding the issue of future dangerousness they will make appropriate and fair decisions; at the very least, they ought to be given the opportunity to do so. Because the majority continues to sanction the practice of hiding the truth in sentencing from citizens, who are asked to decide life and death, I voice my strongest dissent.

Brown v. Dretke, Not Reported in F.Supp.2d, 2004 WL 2793266 (W.D.Tex. 2004) (Habeas).