Executed May 25, 2010 06:19 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

23rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2010

1211th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

11th murderer executed in Texas in 2010

458th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(23) |

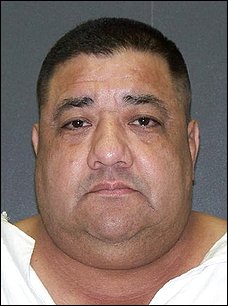

John Avalos Alba H / M / 36 - 54 |

Wendy Alba H / F / 28 |

03-01-01 |

Upon release, he located his wife at the apartment of her friends, Bob Donoho and Gail Webb. Donoho rushed to a back bedroom to place an emergency 911 call. Wendy and Gail Webb leaned against the apartment door with all of their combined strength trying to close and lock the door and prevent Alba from getting in, but Alba overpowered them and forced the door open. He entered the apartment and waved the pistol, laughing and saying to the women, “You bitches deserve this.” Alba then grabbed Wendy by the hair and dragged her to the doorway of the apartment where he pistol-whipped her and shot her to death. Alba then stood over Webb, who was crouched on the floor cowering with her arms over her head, kicked her repeatedly and shot her six times at point-blank range while her young son watched. When Gail’s arm broke and fell away from her head, he shot her once more, in the temple. She lived only because the bullet passed through her sinus cavity and exited through her teeth. Webb survived the attack and testified at Alba’s trial. After shooting at Donoho, Alba left the scene in his own car at a high rate of speed. He was apprehended the next day after a lengthy stand-off with the police at a retail shopping center in Plano.

Citations:

Alba v. State, 905 S.W.2d 581 (Tex.Crim.App. 1995). (Direct Appeal)

Alba v. Thaler, 346 Fed.Appx. 994 (5th Cir. 2009). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

•4 pieces of crispy fried chicken (2 thighs and 2 breasts)

•4 fried pork chops (well done)

•6 cheese enchiladas (2 beef, 2 cheese, 2 pork)

•1 bowl of pico de gallo and a bottle of ketchup

•onion rings

•salad

•1 onion

•6 slices of white bread

•6 cold Cokes.

Last Words:

"I wish I could go back and change it, but I know I can't. Thanks for being beside me. I appreciate you always standing by me and everything ya’ll have done. Tell everyone I love them. I’ll be OK ... you will, too. Just tell everyone I love them. OK, warden, Do it."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Alba)

Alba, John Avalos

Date of Birth: 6/26/55

DR#: 999027

Date Received: 5/8/92

Education: 10 years

Occupation: Construction

Date of Offense: 8/5/91

County of Offense: Collin

Native County: Bastrop, Texas

Race: Hispanic

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Black

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5' 8"

Weight: 190

Prior Prison Record: None.

Summary of incident: Convicted in the August 1991 murder of his wife, Wendy Alba, 28. Alba forced his way into an apartment where his wife was staying with a friend and shot her repeatedly with a .22 caliber pistol. Alba also shot an apartment resident, Gail Webb, who survived. He was arrested in Plano after a stand-off with police, during which he held a gun to his head and threatened to kill himself.

Co-Defendants: None.

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

Media Advisory: John Alba scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about John Avalos Alba, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. on Tuesday, May 25, 2010. A Collin County jury sentenced Alba to death for killing his wife during the course of a burglary. A summary of the evidence presented at trial follows.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

On August 5, 1991, Alba went to a pawn shop in Plano and purchased a .22 caliber semiautomatic pistol and a box of ammunition. At about 10 p.m. that day, Alba tracked his wife Wendy to Allen, where she was staying with friends Robert Donoho and Gail Webb, after unsuccessful attempts to find refuge in local women’s shelters.

Alba tried to force himself into Gail’s apartment, carrying the .22 pistol. Donoho rushed to call 9-1-1, while Wendy and Gail leaned against the apartment door to close and lock the door and prevent Alba from entering. Alba overpowered the two women and forced the door open. Alba entered the apartment and waved the pistol, laughing and saying, “You deserve this.” Alba grabbed Wendy by the hair and dragged her to the doorway of the apartment where he pistol-whipped her before shooting her to death.

Alba left Wendy’s body lying across the threshold and went back into the apartment after Gail. Alba stood over Gail, kicked her repeatedly and shot her six times at point-blank range while her young son watched. When Gail’s arm broke and fell away from her head, he shot her once more in the temple. Gail survived.

Meanwhile, Donoho, still on the line with the 911 dispatcher, came out to see if Alba had left the scene. When Alba saw Donoho in the hallway, he shot at Donoho but missed. Alba left the apartment and shot at the apartment manager, whom he saw running to call for help, but missed. Alba fled the scene. He was arrested after a lengthy stand-off in a shopping center in Plano on August 6, 1991.

CRIMINAL HISTORY

The State presented extensive evidence chronicling Alba’s history of violence and domestic abuse during punishment. There was testimony that Alba molested a 12-year-old girl who was at his apartment for a slumber party in June 1991 and, as a result, was arrested for indecency with a child. While handcuffed but before he was transported to jail, Wendy told Alba she would not get him out of jail. Alba said, “Wendy, you better come get me out of jail or I’ll kill you.” Alba remained in jail until his release on August 4, 1991, the day before he hunted Wendy down and killed her.

On May 29, 1987, Alba and Wendy had an altercation at a bar in Elgin. Alba was seen angrily swinging a spiked metal ball and chain. By the time police arrived, the argument was over but, shortly thereafter, while police were engaged in a routine traffic stop nearby, Alba sped by in his truck with Wendy yelling for help from inside. After a prolonged high-speed chase, Alba slammed on his brakes, jumped out of his truck and approached the officers shouting. Alba resisted arrest and refused to follow instructions, fighting and kicking the officers.

Alba was arrested in Spring 1991 by Allen police officers dispatched on a domestic violence call. When police arrived, Wendy had two black eyes, red marks on her neck and body and the imprint of a shoe on her back where she said Alba had kicked her. Alba told one arresting officer that he knew where the officer lived and he was going to kill the officer’s wife and children.

Police testified that they had responded to similar calls from Wendy in the past. Wendy’s employer and several neighbors and friends testified regarding frequently hearing yelling and screaming, seeing Wendy with bruises and black eyes, seeing Alba physically abuse Wendy and hearing him threaten her. Alba’s ex-wife testified that she had been subject to his violence during their marriage..

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

11/19/1991 -- Alba was indicted for capital murder by a Collin County grand jury.

5/1/1992 --A jury found Alba guilty of capital murder.

5/7/1992 --After a separate penalty hearing, Alba was sentenced to death.

6/28/1995 -- The Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas affirmed Alba’s verdict and sentence.

1/16/1996 --The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari review.

4/15/1998 -- The Texas of Criminal Appeals denied Alba’s application for writ of habeas corpus.

11/2/1998 -- The Supreme Court denied certiorari review.

1/13/2000 -- A U.S. district court denied Alba’s petition for habeas corpus relief.

8/21/2000 -- The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit vacated Alba’s death sentence.

3/1/2001 -- After being retried on sentencing only, a jury again sentenced Alba to death.

4/16/2003 -- The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Alba’s death sentence.

9/10/2003 -- Alba’s motion for rehearing was denied.

10/15/2003 -- The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied application for writ of habeas corpus.

5/24/2004 -- The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari review.

6/23/2005 -- Alba filed an amended petition for writ of habeas corpus in a U.S. District Court.

2/3/2006 -- A federal district court stayed federal proceedings in order for Alba to return to state court on a lethal-injection laim.

9/24/2008 -- The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals dismissed Alba’s application for habeas corpus relief.

12/22/2008 -- A district court denied habeas corpus relief.

10/8/2009 -- The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit denied a certificate of appealability.

1/6/2010 -- Alba filed a petition for writ of certiorari in the U.S. Supreme Court.

05/17/2010 -- The Supreme Court denied his petition for writ of certiorari to the 5th Circuit, ending his federal habeas corpus litigation.

"Collin County man executed in 1991 shooting death of wife," by Michael Graczyk. (Associated Press 05/25/10)

HUNTSVILLE -- A Collin County man, asking forgiveness for killing his estranged wife, was executed Tuesday evening for forcing his way into a neighbor's apartment and shooting his wife not long after he had been released from jail on bail on a child molestation charge.

When a warden asked whether he had a final statement, John Alba, 54, said, "I wish I could go back and change it, but I know I can't." He also addressed his son and daughter, who watched through a window. "Just tell everyone I love them," he said. "Y'all will be OK. I will, too. "OK, warden," he said. "Do it."

Among the witnesses were the parents of the girl he was accused of molesting. As the lethal drugs began to take effect, Alba said he could taste them. "I am starting to go," he said just before slipping into unconsciousness. He was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rejected a request for a reprieve Monday in an appeal that argued that Alba's sentence was improper because he wasn't eligible for life without parole under a law passed just a few years ago, because his Hispanic race illegally figured into his sentencing, because he shouldn't have been charged with capital murder and because his sentencing was unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review that appeal Tuesday, about 30 minutes before he was taken to the death chamber. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles also denied a clemency request. Alba declined to speak with reporters as his execution date neared.

Rocky relationship

Alba and his wife, Wendy, 28, had a rocky marriage marked by alcohol abuse, infidelity and domestic violence, according to trial testimony. While Alba was in jail for several weeks after a 12-year-old girl told police that he fondled her, Wendy Alba took refuge in a neighbor's apartment in Allen while she was trying to find a women's shelter.

Not long after leaving jail Aug. 5, 1991, Alba bought a .22-caliber semiautomatic pistol at a Plano pawn shop. He showed up at the apartment, forced his way in and shot Wendy Alba. The neighbor, who was wounded, testified against Alba. Evidence showed that from jail, the former construction worker had written his wife numerous "extremely threatening letters, love notes with a lot of sarcasm," Curtis Howard, a Collin County assistant district attorney who prosecuted Alba, said last week. "They had a long history of abuse within the relationship," he said.

A woman who had a child with Alba testified that he'd been drinking the day of the shooting. Other testimony showed that authorities responded to numerous domestic violence calls involving the couple and that Wendy Alba was terrified of her husband.

According to other evidence presented at his trial: Alba fired at the apartment manager as he fled. He encountered a police officer and told him that he was getting out of the area because a crazy man was shooting a gun. The officer wasn't aware that Alba was the shooter. Alba sped off in his own car, dumped it at a Plano bowling alley and carjacked a teenager, forcing the 16-year-old to drive him into a nearby neighborhood. He spent the night with a woman who had his child. That morning, he returned to the apartment complex where the shooting occurred, saw an officer and ran to a shopping mall, where he began a standoff with police by threatening to kill himself. Two hours later, a police SWAT team used a stun grenade and tear gas to end the standoff and arrest him.

Alba was the 11th prisoner executed this year in Texas, the nation's busiest death penalty state.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

John Avalos Alba, 54, was executed by lethal injection on 25 May 2010 in Huntsville, Texas for killing his estranged wife after invading her home.

In June 1991, Alba was accused of molesting a 12-year-old girl who was at his apartment for a slumber party. A warrant was issued for his arrest on the charge of indecency with a child. As officers were taking him to jail in handcuffs, Alba told his wife, "Wendy, you better come get me out of jail, or I'll kill you." While Alba was in jail, he wrote numerous threatening letters to his wife. She, meanwhile, moved in with friends Robert Donoho and Gail Webb in their apartment in Allen, north of Dallas. She was also trying to find residence in a women's shelter.

Alba was released from jail on 4 August 1991. The next day, he purchased a .22-caliber semiautomatic pistol and a box of ammunition from a pawn shop in Plano and tracked down his wife. At about 10 p.m., he began attempting to force his way into the apartment. While Donoho called 9-1-1, Wendy, 28, and Webb leaned against the door. Alba, 36, overpowered the two women and forced the door open. He then entered the apartment, grabbed Wendy by the hair, and dragged her to the doorway, where he pistol-whipped her before shooting her to death. He left he body lying across the threshold, then went back inside. He kicked Webb repeatedly and shot her seven times, including once in the temple. She survived. Donoho, who was still on the phone, then came out. Alba shot at him, but missed. Alba then left the apartment. He saw the manager running to call for help and shot at him, but missed.

While he was fleeing, Alba encountered a police officer. He told the officer he was getting out of the area because a crazy man was shooting a gun. The officer, unaware that Alba was the shooter, let him go. Alba then drove in his own car to a bowling alley in Plano. There, he carjacked a 16-year-old, forcing him to drive him to a nearby neighborhood. He spent the night with the mother of one of his children. The next morning, Alba returned to the apartment complex where he killed his wife. Seeing a police officer, he ran to a shopping mall and set up a 2-hour standoff with police, during which he held a gun to his head and threatened to kill himself. A SWAT team used a stun grenade and tear gas to subdue him.

In order for a murder to qualify as capital murder, one or more aggravating factors must exist. In Alba's case, the aggravating factor was the burglary he committed when he broke into apartment. The defense did not deny that Alba broke into the apartment, killed Wendy at the doorway, and went back inside to shoot Webb. They argued, though, that he was standing outside the apartment doorway when he committed the murder, and therefore he was not committing burglary at that moment.

At the punishment hearing, Allen police officers testified that they responded to a domestic violence call in the spring of 1991. Wendy had two black eyes, red marks on her neck and body, and a shoe imprint on her back. Alba told one of the officers who arrested him that he knew where the officer lived and was going to kill his wife and children. Other officers testified that they had responded to similar domestic violence calls from Wendy. Neighbors and friends testified that they frequently heard yelling and screaming, saw Wendy with bruises and black eyes, and saw Alba abuse and threaten her. Alba's ex-wife also testified that he was violent towards her during their marriage. He had no prior felony convictions.

A jury convicted Alba of capital murder in May 1992 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in June 1995.

An issue that arose during another Texas death row prisoner's case resulted in Alba's death sentence being vacated. In 2000, Texas Attorney General John Cornyn confessed that Dr. Walter Quijano, acting as an expert witness for the prosecution, offered racially biased testimony at Victor Saldano's capital punishment hearing. Specifically, Quijano stated, "because [Saldano] is Hispanic, this was a factor weighing in favor of future dangerousness." Following this disclosure, Cornyn reviewed all capital cases in which Quijano testified and a death sentence was given. In June 2000, he announced that six other cases - including John Alba's - were tainted by racially biased testimony from Dr. Quijano, and recommended that all of their death sentences be vacated. Accordingly, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated Alba's death sentence in August 2000.

The state held a new sentencing hearing for Alba. At this hearing, he testified that he did not deliberately kill his wife; it was a "bad reaction." He stated that he bought the gun on the day of the shooting as protection from a cousin. A jury resentenced Alba to death in March 2001. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the sentence in April 2003. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied.

Alba declined requests to speak with reporters as his execution date approached. A web site operated by a supporter of his described the circumstances of the murder quite differently than the trial record. According to the site, Wendy Alba also physically abused John, and she had sexual affairs with several other men. The site also stated the friends she moved in with were drug dealers. John went to visit his children and got into an argument with Wendy over the environment where his children were living. "He asked Wendy if she had been unfaithful again, and tragically the gun was in his possession at the same time of the chilling details of Wendy's latest liaisons were revealed."

Alba's execution was attended by members of his victim's family, the parents of the daughter he was accused of molesting, and his own son and daughter. "I am sorry for taking someone so precious to you and to my kids," he said in his last statement. "I wish I could go back and change it, but I know I can't." Turning to his loved ones, he said, "Thanks for being beside me. I appreciate you always standing by me and everything y'all have done. ... Just tell everyone I love them. Y'all will be OK. I will, too. OK, warden. Do it." The lethal injection was then started. Alba said he could taste the chemicals. He said "I am starting to go," then lost consciousness. He was pronounced dead at 6:19 p.m.

"Alba executed for wife’s shooting," by Mary Rainwater. (May 25, 2010)

HUNTSVILLE — A Dallas area man was executed by lethal injection Tuesday for the shooting death of his estranged wife in her apartment almost two decades ago.

When asked to give a final statement, John Alba, 54, first asked for forgiveness. “I am sorry for taking someone so precious to you and to my kids,” he said to the victim’s family. “I wish I could take it all back and change it, but I know I can’t.” He then turned his sentiments to his own family. “Thanks for being beside me,” Alba said. “I appreciate you always standing by me and everything ya’ll have done. “Tell everyone I love them,” he added. “I’ll be OK ... you will, too.”

Shortly after instructing the warden, “Let’s do it,” Alba stated he could taste the drugs already taking effect. He was pronounced dead just nine minutes later, at 6:19 p.m.

Alba and his wife, Wendy, 28, had a rocky marriage marked by alcohol abuse and infidelity and domestic violence, according to trial testimony. On the day of the shooting, Alba was released from jail after posting bail on a charge of molesting a 12-year-old girl. The girl’s parents were among the people in the death chamber who watched Alba die.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rejected a request for a reprieve Monday in an appeal that argued that Alba’s sentence was improper because he wasn’t eligible for life without parole under a law passed just a few years ago, that his Hispanic race illegally figured into his sentencing, that he shouldn’t have been charged with capital murder and that his sentencing was unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to review that appeal Tuesday, about 30 minutes before he was taken to the death chamber. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles also denied a clemency request. Alba declined to speak with reporters as his execution date neared.

Testimony at his trial showed his wife had taken refuge in a neighbor’s apartment in Allen while she was trying to find a women’s shelter. Alba showed up, forced his way in and shot her with the .22-caliber semiautomatic pistol he bought that day.

Alba was arrested the day after the shooting in a parking lot not far from the apartment after a two-hour standoff with police in which he held a gun to his head and threatened to kill himself. A police SWAT team ended the stalemate with tear gas and a stun grenade.

Alba was the 11th prisoner executed this year in Texas, the nation’s busiest death penalty state. Next week, convicted killer George Jones faces lethal injection, on June 2, for a fatal carjacking robbery in Dallas 17 years ago.

On the morning of August 5, 1991, John Avalos Alba went to the Plano Pawn Shop and purchased a .22-caliber semi-automatic pistol and a box of ammunition. At approximately 10:00 p.m. that evening, Alba arrived at the apartment of Gail Webb and Bob Donoho looking for his wife, Wendy. Upon finding Wendy at the residence, Alba sought to gain entry while Wendy and Webb attempted to shut the door on his arm. Alba eventually fired his pistol into the back of the door and forced his way into the apartment.

He told Wendy and Webb that "you bitches deserve this." Alba then grabbed Wendy by the hair and pulled her halfway out of the apartment where he proceeded to pistol whip and shoot her three times. He shot her in the back of her head, her buttocks, and the middle of her back severing her spinal cord. One of these injuries actually occurred after appellant shot at Webb and Donoho and was leaving the apartment. Wendy later died at the hospital. Alba next went after Webb who had run into the kitchen and was now crouching on the floor. Alba stood over her and laughingly stated, "you deserve to die, bitch." He then shot her six times in the head and arms. Webb survived the attack. During this time, Donoho had gone to the back bedroom to place an emergency "911" call. When he came out to check on Wendy and Webb, Alba asked him, "You want some of this?" and fired a shot at Donoho's head, missing by about twelve to fifteen inches.

Canadian Coalition Against the Death Penalty

Visit John's Official webpage at: http://www.johnalba.com/

My days on Death Row (D/R) are spent locked away 23-hours-a-day in a 6-x-9 cell. We are allowed to recreate for one-hour each day. One shower a day.

There are no TV's on Texas D/R. We are allowed to buy a small plastic radio from the prison commissary store, and that is our 'entertainment'. We are allowed to correspond with free-world people. So as one can imagine, mail-call in the evenings are our 'highlight' of the day, what we look forward to each day. I would love to have the opportunity to write to someone who is both open minded and honest, but with a good sense of humour. I am a sincere person and I don't play head games with my pen-friends, and I am not looking for romance. I have been on Texas Death Row for over 10 years. I have 4 children and 6 grandchildren. I like to read books on history, mysteries, autobiographies, some classics. Tough, I'll read anything ! I like meeting new people and building freindships/correpondences, writing letters, receiving mail, listening to music from the 60's-80's. I also enjoy being outdoors, camping, hiking, fishing, swimming, and barbecuing, and just breathing the fresh air. I like having a garden and growing my own vegetables. Thank you so much for your time.

John Alba #999027

Or send an email to penpal@johnalba.com and it will be forwarded by his supporters.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Penpal’s a killer on Death Row --- From The News Shopper

Mexican John Alba is on Death Row for shooting his wife 11 years ago. Reporter EMMA COUTTS-WOOD talks to Brockley student Amy Greene who has been writing to him since she was 15 ...

FOR many British people, Death Row is something we hear about on the television and in American films like Dead Man Walking but we do not know much about it.

But for the last eight years, 23-year-old student Amy Greene, from Brockley, has been writing to John Alba who is on Death Row in Texas for shooting his wife, Wendy, on August 5 1991, after discovering she was having an affair.

His case is high-profile in America because he is Mexican and his 28-year-old wife was white and there have been allegations of racism during the trial.

The 47-year-old is now appealing for his sentence to be reduced to a life prison sentence.

Although John Alba receives very little support from his fellow Americans because of the nature of the case, he receives letters every week from Amy and her family and she has even been over to America to see him several times.

Amy, of Manor Avenue, started writing to John when she was 15 and doing a project on capital

punishment at school.

Now a sociology student at Goldsmiths College in London, she is still writing to him and

campaigning for his sentence to be reduced.

She said: "I got his name and address from a friend of my mum who was writing to him at the

time. "Now he has become a friend and we write twice a week. He is kind and sensitive and in his letters he talks a lot about his family. I have been over to America to see him a few times.

"He has pleaded guilty to shooting his wife and knows he deserves a punishment but to get his

sentence reduced, he has to prove the murder was not pre-meditated and he is not a threat to

society."

Amy claims there have been flaws in the case. "His lawyer says the prosecution was racist and

even the jurors were against inter-racial marriages. I was really touched when I met his four

children. I realised how important it was to campaign for his sentence to be reduced."

Amy has been in contact with his lawyer and has set up a fund for John.

She added: "I want to see justice for John. He doesn't deserve to be on death row."

11:50 Tuesday 16th July 2002.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Pen Pal Request from: http://www.internazionale.it/carcere/carcere.html

"Dear Internazionale, my name is John Alba, and I am a Death Row prisoner. I am writing to you, because I would like to ask you if you can help me find some Italian pen-friends, who would like to correspond with me? (...) I have 4 children and 6 grandchildren with another on the way and so I am feeling like an old man. :-) Days here can get very long and very lonely, and so mail call is the chance for us to disappear into another world for a moment or more.

If anyone would like to know more about me then please look at a website that a friend has made for me www.johnalba.com. I really look forward to receiving any letters that will come my way."

Home - Case - Racism in the trial - Racial Disparities - Personal - Maybe Death is Heaven - Donation Details - Pen Pal Request - Official TDCJ Page - Appeal Stages - A Visit to Texas - Walk for Justice 2 - Walk for Justice 1 - Links

Greetings from Texas death row

I am writing on behalf of my friend, John Alba, a Mexican-American man on death row at the Polunsky unit in Livingston, Texas. He is a good and kind man who is appealing against the death penalty, and is in desperate need of help. He has been on death row since May 1992 for the shooting of his wife. No one condones this crime, but there were many mitigating circumstances that have never been heard in front of a jury, and so all we are asking for is a chance to open your eyes and hopefully your heart to the situation he is in. His trial has been full of ineffective representation and racial prejudice, and now he needs the support of people like you to help him and his family.

please read on...

Collin County has a Hispanic community that comprises only 10.3% of the general population and the African American a mere 5.2%. But during the past ten years Collin County's Prosecutors have used their discretion to insure that 100% of all death sentenced individuals are minorities, and all but one of them were sent to death row for killing a white person.

more...

Ways of helping John

There are two ways to help. You can quickly and simply make a secure donation online with paypal. Alternatively, there is an account set up for John, based in the UK. account details If you could spare a moment of your time, please write to John. Also if you would like any emails forwarded to John or you would like to ask any questions please don't hesitate to contact him at the link below.

contact details

Alba v. State, 905 S.W.2d 581 (Tex.Crim.App. 1995). (Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted of capital murder for intentionally causing death during course of burglary, and was sentenced to death, in the 199th Judicial District Court, Collin County, John R. Roach, J., and defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, McCormick, P.J., held that: (1) state did not impermissibly use killing of defendant's wife as both primary offense of murder and as element of underlying offense of burglary, since defendant also committed two completely separate felonies of attempted murder; (2) extraneous offense of kidnapping two teenage boys was admissible as necessarily related circumstance showing defendant's flight from arrest; (3) evidence of extramarital sexual relationship by victim, who was defendant's wife, was inadmissible; (4) defendant was not prejudiced by conversation between juror and detention officer regarding juror's receipt of computerized collect call from unknown county jail; and (5) trial court properly denied defendant's request for voir dire examination of state's psychiatric expert outside presence of jury, and, even if denial of request was erroneous, it was clearly harmless. Affirmed.

Keller, J., concurred in point of error six and otherwise joined opinion of the court. Baird, J., filed concurring opinion in which Overstreet and Maloney, JJ., joined. Clinton, J., filed dissenting opinion.

McCORMICK, Presiding Judge.

Appellant was convicted of capital murder for intentionally causing the death of an individual during the course of burglary. V.T.C.A., Penal Code, Section 19.03(a)(2). The jury answered the special issues affirmatively and punishment was assessed accordingly at death. Article 37.071(b), V.A.C.C.P. FN1 Appeal to this Court is automatic. Article 37.071(h). Appellant raises eight points of error. We will affirm. FN1. Unless otherwise indicated, all references to articles are to those in the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure.

Appellant does not challenge the sufficiency of the evidence. However, a brief summary of the facts will be helpful in resolving the points of error.

Viewed in the light most favorable to the verdict, the evidence at trial showed: On the morning of August 5, 1991, appellant went to the Plano Pawn Shop and purchased a .22-caliber semi-automatic pistol and a box of ammunition. At approximately 10:00 p.m. that evening, appellant arrived at the apartment of Gail Webb and Bob Donoho looking for his wife, Wendy. Upon finding Wendy at the residence, appellant sought to gain entry while Wendy and Webb attempted to shut the door on his arm. Appellant eventually fired his pistol into the back of the door and forced his way into the apartment. He told Wendy and Webb that “you bitches deserve this.” Appellant then grabbed Wendy by the hair and pulled her halfway out of the apartment where he proceeded to pistol whip and shoot her three times. He shot her in the back of her head, her buttocks, and the middle of her back severing her spinal cord.FN2 She later died at the hospital. FN2. One of these injuries actually occurred after appellant shot at Webb and Donoho and was leaving the apartment.

Appellant next went after Webb who had run into the kitchen and was now crouching on the floor. Appellant stood over her and laughingly stated, “you deserve to die, bitch.” He then shot her six times in the head and arms. Webb survived the attack.

During this time, Donoho had gone to the back bedroom to place an emergency “911” call. When he came out to check on Wendy and Webb, appellant asked him, “You want some of this?” and fired a shot at Donoho's head, missing by about twelve to fifteen inches.

Upon leaving the apartment, appellant was confronted by Misty Magers, the apartment manager, her boyfriend, and a neighbor. When the manager ran to call for help, appellant fired a shot in her direction and yelled, “I'm going to get you too, Misty.” He then turned the gun on the other two and asked, “Do you want any of this?” They let appellant pass. As appellant was attempting to finally leave the complex, he ran into Officer Wallace Moreland of the Allen Police Department. Appellant told Moreland, “I'm getting the hell out of here. There's a crazy son of a bitch over there shooting people.” Appellant then left. Moreland did not stop him because he was unaware that appellant was involved in the crime.

Appellant left the scene in his own car at a high rate of speed. He later abandoned his vehicle in Plano and fled on foot to a Plano bowling alley. There he came upon Ryan Clay, a teenager, working on a car in the parking lot. Appellant asked for a ride and when Clay stated that it was not his car appellant pointed his gun at him and again asked for a ride. Clay complied. However, before they could leave the parking lot, sixteen-year old Michael Carr, the owner of the car, stopped them. Carr, realizing something was not right, drove appellant as requested to a nearby neighborhood. Appellant was apprehended on August 6, 1991, after a lengthy stand-off with the police at a retail shopping center in Plano.

In his first point of error, appellant complains that the trial court erred in receiving the jury's verdict of guilty of capital murder under V.T.C.A., Penal Code, Section 19.03(a)(2), and subsequently the sentence of death, because Section 19.03(a)(2) was unconstitutionally applied to him. FN3 Specifically, he asserts that the State used the killing of appellant's wife as the primary offense of murder and as an element of the underlying offense of burglary. He claims such “bootstrapping” violates the “narrowing” test under Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 92 S.Ct. 2726, 33 L.Ed.2d 346 (1972), and Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262, 96 S.Ct. 2950, 49 L.Ed.2d 929 (1976).FN4 We do not need to reach these arguments because appellant's complaint is without merit.

FN3. Appellant concedes that the Texas death penalty scheme is constitutional. See Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262, 96 S.Ct. 2950, 49 L.Ed.2d 929 (1976). FN4. The United States Supreme Court held that V.T.C.A., Penal Code, Section 19.03 was constitutional because it narrowed the circumstances under which the State might seek the death penalty to a “small group of narrowly defined and particularly brutal offenses.” Jurek, 428 U.S. at 270, 273-75, 96 S.Ct. at 2955, 2957.

[1] Section 19.03(a)(2) states that “[a] person commits [a capital] offense if he commits murder [by intentionally or knowingly causing the death of an individual] in the course of committing or attempting to commit ... burglary....” A person commits burglary if, without the effective consent of the owner, he enters a habitation, or a building not then open to the public, with the intent to commit a felony or theft. V.T.C.A., Penal Code, Section 30.02(a)(1). The indictment in the instant cause alleged that appellant

“... intentionally cause[d] the death of an individual, Wendy Alba, by shooting the said Wendy Alba with a deadly weapon, namely, a firearm, and the said defendant was then and there in the course of committing and attempting to commit the offense of burglary of a habitation of Robert Guinn Donoho; ...”

In the instant case, appellant beat and murdered his wife after forcing his way into Webb's apartment at gunpoint, attempted to murder Webb by shooting her six times, and attempted to murder Donoho by shooting at him once. Appellant committed two completely separate felonies of attempted murder after forcing his way into the apartment. On appeal, he ignores these additional felonies. There was no need for the State to use the murder of appellant's wife as both the primary offense and an element of burglary. Further, the jury was instructed on the felony offense of attempted murder.FN5 Point of error one is overruled.

FN5. The jury was specifically charged:

“Our law provides that a person commits the offense of attempted murder if with specific intent to commit murder he does an act amounting to more than mere preparation that tends but fails to effect the commission of the offense of murder. The offense of attempted murder is a felony offense.” (Emphasis added.)

In his second point of error, appellant complains that the trial court erred in failing to quash the indictment. Because appellant was charged with murder in the course of a burglary, he believes that fair notice dictates that the State should have been required to specifically allege the elements of the underlying offense of burglary. Further, he claims that because the indictment lacked specificity, the State was able to “bootstrap a ‘burglary by murder’ into a capital murder” by using the murder of Wendy Alba as both the primary and underlying offenses.

Appellant acknowledges that we have repeatedly held that an indictment need not allege the constituent elements of the underlying offense which elevates murder to capital murder. Barnes v. State, 876 S.W.2d 316, 323 (Tex.Cr.App.), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 861, 115 S.Ct. 174, 130 L.Ed.2d 110 (1994) (need not allege the constituent elements of burglary); Beathard v. State, 767 S.W.2d 423, 431 (Tex.Cr.App.1989) (burglary); Marquez v. State, 725 S.W.2d 217, 236 (Tex.Cr.App.), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 872, 108 S.Ct. 201, 98 L.Ed.2d 152 (1987) (aggravated sexual assault). He raises no novel argument to persuade us to revisit these holdings. We further note that appellant's “bootstrapping” argument is sufficiently addressed in our discussion of the previous point of error. Point of error two is overruled.

Point of error three avers that the trial court erred in admitting evidence of the extraneous offense of kidnapping the two teenage boys at the guilt/innocence phase of trial. Specifically, he contends that the evidence was not relevant under Texas Rule of Criminal Evidence 404(b).FN6 He further states that if the evidence was relevant its prejudicial impact outweighs its probative value. See Tex.R.Crim.Evid. 403.

FN6. Rule 404(b) states:

“Evidence of other crimes, wrongs, or acts is not admissible to prove the character of a person in order to show that he acted in conformity therewith. It may, however, be admissible for other purposes, such as proof of motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, or absence of mistake or accident, provided, upon timely request by the accused, reasonable notice is given in advance of trial of intent to introduce in the State's case in chief such evidence other than that arising in the same transaction.”

Appellant does complain that he was not given notice by the State.

It is improper to try a defendant for being a criminal, generally. Nobles v. State, 843 S.W.2d 503, 514 (Tex.Cr.App.1992). Therefore, an extraneous offense must be shown to be relevant apart from character conformity before it may be admitted into evidence. McFarland v. State, 845 S.W.2d 824, 837 (Tex.Cr.App.1992), cert. denied, 508 U.S. 963, 113 S.Ct. 2937, 124 L.Ed.2d 686 (1993). If relevant, then the extraneous offense must be shown to have more probative value than prejudicial impact. Id.; Foster v. State, 779 S.W.2d 845, 858 (Tex.Cr.App.1989), cert. denied, 494 U.S. 1039, 110 S.Ct. 1505, 108 L.Ed.2d 639 (1990). However, the trial court need not engage in this balancing test unless the opponent of the evidence further objects under Rule 403. McFarland, 845 S.W.2d at 837. If the proper objection is made, then the decision on admissibility lies within the discretion of the trial court. Id.; Foster, 779 S.W.2d at 858. Appellant objected under Rules 401, 403 and 404(b).

We have previously held that flight is admissible as a circumstance from which an inference of guilt may be drawn. Foster, 779 S.W.2d at 859. So long as the extraneous offense is shown to be a necessarily related circumstance of the defendant's flight, it may be admitted to the jury. Id.

As appellant explains, the complained-of evidence showed:

[Ryan Clay] was outside a Plano bowling alley working on some speakers in a friend's car when he was approached by a man he identified as appellant. The man asked for a ride and when Clay stated it was not his car the man pulled a gun. Clay and the man got into the car and, as they were driving out of the parking lot, Clay's friend, Michael Eugene Carr, came out of the bowling alley and stopped them. Clay told Carr this guy needs a ride. Clay got in the rear passenger Seat and Carr began to drive. Clay believed the man had the gun between his legs, however he did not point the gun at Carr or even exhibit it to Carr. Clay and Carr were with the man for maybe 10 to 15 minutes.

In the context of the evidence previously adduced at trial, the evidence also showed that the extraneous offense occurred: (1) within one hour of the murder, (2) after appellant had deceived a police officer when he left the crime scene, and (3) after appellant had abandoned his own car. The evidence of the extraneous offense was a necessarily related circumstance showing appellant's flight from arrest. The trial court did not abuse its discretion. Foster, 779 S.W.2d at 859-60. Point of error three is overruled.

In appellant's fourth point of error, he contends that the trial court erred in refusing to admit the testimony of Mike Engle concerning his sexual relationship with Wendy Alba. The trial court excluded this testimony regarding Engle's one-time sexual encounter with appellant's wife because it was irrelevant. Appellant argues the testimony was relevant because it contained evidence that his wife had a reason to fear him other than that he was just “mean and vicious.”

Evidence proffered at trial showed that Wendy Alba was afraid of her husband. She spent the afternoon of August 4, 1991, calling women's shelters and treatment centers looking for a place to go. She and her children stayed at a neighbor's apartment.

Appellant argues that he was entitled to present evidence that, “if it became known to appellant,” might have given “rise to [his] sudden level of passion” and, therefore, the deceased might have reason to fear appellant. We can only assume that appellant wished to proffer this evidence to show his motive for the crime. On appeal, as at trial, appellant presents no evidence that he had any knowledge of his wife's infidelity at the time of the instant crime nor that his wife should fear for her life if he did. Because appellant explicitly offered Engle's testimony for the purpose of showing why Wendy Alba might fear him, it was not relevant and was, therefore, inadmissible. See Rules 401 and 402. Point of error four is overruled.

In point of error number five, appellant complains that the trial court erred in denying appellant's motion for mistrial made as a result of unauthorized juror conversations. The record reveals that during the punishment phase prior to deliberations, Juror Botts received a computerized collect call from an unknown county jail. Botts refused to accept the charges and the call was terminated. Botts then notified Collin County Jail personnel, including Detention Officer Thomas Byers, and the bailiff in the instant case, Novaline Varner. Appellant specifically complains about the conversation between Botts and Officer Byers.

Article 36.22 states:

“No person shall be permitted to be with a jury while it is deliberating. No person shall be permitted to converse with a juror about the case on trial except in the presence and by the permission of the court.”

When a juror converses with an unauthorized person, injury is presumed. Green v. State, 840 S.W.2d 394, 406 (Tex.Cr.App.1992), cert. denied, 507 U.S. 1020, 113 S.Ct. 1819, 123 L.Ed.2d 449 (1993). However, the presumption is rebuttable if it is shown that the case was not discussed or that nothing prejudicial to the accused was said, then appellant has not been injured and the verdict will be upheld. Id.

At the hearing outside the presence of the jury, Botts stated that after receiving the collect call he immediately phoned the Collin County Jail. He testified that Officer Byers told him that “there had been similar problems of this nature” and that “there had been problems with this trial of that type having to do with the defense attorneys.” The following then occurred:

“THE COURT: Now, have you-this conversation you had with this person at the jail, did anyone ever indicate to you that anything was the result of having been done by the defendant in this case, or by his lawyers?

“JUROR: No. It was very unclear as to the nature of the problem that he indicated to me. I did not understand what he was saying; whether he was saying that the defendant was involved, or who may have been originating calls, or anything of that nature. It was very obscure as to what he was telling me, and I did not understand what he was saying.

“THE COURT: Did you attribute anything he might have said to the conduct, or some claimed conduct, by him on the part of this defendant or the defense attorney or-

“JUROR: No, sir. Nothing that he said could have led me to believe that I could identify the source of the problem at all.

“THE COURT: All right. Well I'm-did you take anything he told you to be some statement of some fact by him of some misconduct on the part of either the defendant in this case, or his counsel?

“JUROR: No, sir. Nothing that he said would have caused me to make that kind of conclusion.

* * * * * *

“THE COURT: But whatever it was-and you've described what it was that was commented about to you-it has no way influenced your view in this case in any way whatsoever up to Friday afternoon when you left the courthouse?

“JUROR: No, sir.

“THE COURT: Have you reached any kind of conclusion at all about any-from what you may have been told by anyone at the jail about any acts of misconduct by either the defendant or by his-or his counsel in this case?

“JUROR: No, sir.

* * * * * *

“THE COURT: So I'm not asking you whether-what your views are, or anything like that; but I'm just saying that, do you believe that you can continue to be a juror who can fairly and impartially judge the evidence as you hear it through the rest of this trial?

“JUROR: Yes, sir, I do.”

Botts further testified that he did not discuss the matter with anyone other than those already mentioned and his wife. No other jurors were informed of the incident. On these facts,FN7 the trial court was justified in concluding that appellant suffered no prejudice. Point of error five is overruled.

FN7. We note that the bailiff and Officer Botts each had different versions of the foregoing events. However, because it is the juror's views that may be prejudiced, we consider only the juror's perceptions.

Appellant's sixth point of error alleges that the trial court erred in denying his request for a voir dire examination of the State's psychiatric expert outside the presence of the jury. Tex.R.Crim.Evid. 705(b), infra.

Under Rule 705(b), infra, a criminal defendant is undeniably entitled, upon timely request, “to conduct a voir dire examination directed to the underlying facts or data upon which the opinion [of the State's expert] is based.” The trial court must allow this examination to be conducted “[p]rior to the expert giving his opinion” and “out of the hearing of the jury.” Affording a defendant the chance to voir dire the State's expert witnesses gives defense counsel the opportunity to determine the foundation of the expert's opinion without fear of eliciting damaging hearsay or other inadmissible evidence in the jury's presence. Goss v. State, 826 S.W.2d 162, 168 (Tex.Cr.App.1992), cert. denied, 509 U.S. 922, 113 S.Ct. 3035, 125 L.Ed.2d 722 (1993). A Rule 705(b) hearing may also supply defense counsel with sufficient ammunition to make a timely objection to the expert's testimony on the ground that it lacks a sufficient basis for admissibility. Id. Because Rule 705(b) is mandatory, a trial judge's denial of a timely and proper motion for such hearing would constitute error. Id. In such a case, a reviewing court would then be required to decide whether the trial judge's error was so harmful as to require a reversal. Id.

Appellant in the instant case was denied the opportunity to voir dire the State's expert out of the presence of the jury. Tex.R.Crim.Evid. 705(b) provides:

“(b) Voir Dire. Prior to the expert giving his opinion or disclosing the underlying facts or data, a party against whom the opinion is offered shall, upon request, be permitted to conduct a voir dire examination directed to the underlying facts or data upon which the opinion is based. This examination shall be conducted out of the hearing of the jury.” (Emphasis supplied.)

At the punishment phase of the trial the State called Dr. Richard Coons as a psychiatric expert. After qualifying Dr. Coons as an expert, to which there was no objection, the prosecutor stated, “I want to ask you a hypothetical question based on what I believe is the evidence in this case, and then I'm going to ask you for an opinion-some opinions on some issues in this case.” The prosecutor then formulated a hypothetical question (comprising thirteen pages of the record), and then asked Dr. Coons his opinion as to the future dangerousness of appellant. At this point appellant objected and asked for the voir dire hearing provided for by Rule 705(b). The trial court overruled the objection and Dr. Coons thereafter expressed his opinion. FN8

FN8. Following the overruling of appellant's objection, but before Dr. Coons gave his opinion, appellant's counsel again objected but acknowledged that his request for a Rule 705(b) hearing was denied “since there appears to be evidence before the jury on which the opinion is based.” Later, the prosecution sought to have Dr. Coons give an opinion as to whether the defendant would be a threat to the prison society. Appellant objected that there were no underlying facts for the opinion and asked for a hearing under Rule 705(b). The trial court sustained appellant's objection and the State made no further effort to have Dr. Coons testify. Obviously the trial court was cognizant of Rule 705.

Rule 705 permits an abbreviated method of laying the groundwork before asking for the expert's opinion. Texas Rules of Evidence Manual, Wendorf, Schlueter, and Barton, 3rd Ed. (1994), VII-71.FN9 The criminal version of Rule 705 has no counterpart in either the civil or federal rules. Id, VII-74.

FN9. The purpose of Rule 705 is wholly consistent with the purpose of the Rules of Evidence. Rule 102 provides:

“These rules shall be construed to secure fairness in administration, elimination of unjustifiable expense and delay, and promotion of growth and development of the law of evidence to the end that the truth may be ascertained and proceedings justly determined.” (Emphasis added.) Tex.R.Crim.Evid. 102.

[17] The focus of Rule 705(b) is to prevent the jury from hearing the underlying facts and data which might ultimately be ruled as inadmissible. Wendorf, et al, supra, at VII-75. See and cf. Vasquez v. State, 819 S.W.2d 932, 934-35 (Tex.App.-Corpus Christi 1991, pet. ref.). The purpose of the Rules of Evidence, Rule 102, and the purpose of Rule 705(b), have been fully satisfied. The jury had before it all facts and data upon which Dr. Coons formulated his opinion.

Under the facts presented here, we cannot say that the trial court erred in denying the Rule 705(b) hearing. Further, even if we could conclude that such was error, it was clearly harmless.FN10 Point of error six is overruled.

FN10. Among other things, the dissent takes issue with our disposition of the sixth point of error partly because the dissenter believes the rationale for our disposition of this point is not well-stated, and, in any event, is wrong. However, the rationale should be self-evident. Rule 705(b) allows the party opposing the opinion to voir dire the expert on the “underlying facts or data upon which the opinion is based.” Here, the “underlying facts and data” were made known to appellant in the hypothetical question which incorporated the facts of the case. Therefore, there was no error in not allowing appellant to voir dire the expert to “discover” matters which appellant already knew. The dissent would have this Court grant this legally guilty and fairly tried appellant “at least” a new punishment hearing because he was not allowed to “discover” matters already known to him. Such a result would be absurd.

In addition, the dissenters' interpretation of the scope of Rule 705(b) is wrong as well. The dissent says Rule 705(b) should allow a defendant to conduct a fishing expedition on, for example, the “psychiatric basis for concluding from those historical facts that appellant would constitute a continuing threat to society.” However, the “plain language” of Rule 705(b) speaks to the “underlying facts or data.” It does not say anything about “psychiatric basis.” The dissenter's interpretation of Rule 705(b) would defeat the very purpose of the rule which is “to quickly and efficiently elicit helpful expert opinions which aid the jury in its fact finding task.” Vasquez v. State, 819 S.W.2d 932, 934-35 (Tex.App.-Corpus Christi 1991, pet. ref'd). Criminal defendants have the opportunity to cross-examine the State's experts and to present experts of their own. Our interpretation of Rule 705(b) works no “unfairness” to criminal defendants in this state.

However, what the dissent really appears to be upset about is allowing expert opinions, like the one here, in cases like this. See, e.g., Flores v. State, 871 S.W.2d 714, 724-25 (Tex.Cr.App.1993) (Clinton, J., dissenting). The dissent seems to want to bring back the old discredited objection that the expert testimony “invades the province of the jury.” Of course, the reason the State presents these opinions in cases like this is that this Court from time to time has “invaded the province of the jury” in conducting a sufficiency review on the second special issue on “future dangerousness.” See id. In some cases, this Court has usurped the jury's function and quite confidently stated, for example, that “there is nothing in the facts themselves so heinous or shocking as to evince a particularly ‘dangerous aberration of character’ probative of future dangerousness....” See id.

In his seventh point of error, appellant asserts that the trial court should have held relevancy hearings prior to the admission of testimony regarding various extraneous offenses. He concedes in his argument “that evidence of extraneous crimes or bad conduct has been held relevant to the special issues submitted in a capital murder punishment hearing.” See Harris v. State, 827 S.W.2d 949, 962 (Tex.Cr.App.), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 942, 113 S.Ct. 381, 121 L.Ed.2d 292 (1992); Ramirez v. State, 815 S.W.2d 636, 653 (Tex.Cr.App.1991). Appellant raises no new argument to persuade us to reconsider these holdings.FN11 Point of error seven is overruled.

FN11. Appellant further argues that relevancy hearings should have been allowed in order for him to challenge the veracity of the witnesses. Appellant misconstrues the law. The veracity of a witness is a question of fact for the jury and is properly addressed during cross-examination.

Finally, in his eighth point of error, appellant complains that the trial court erred in overruling his objections to the court's charge at the guilt/innocence phase. Appellant claims that the charge allows the State to again “bootstrap” the murder of Wendy as both the underlying offense of burglary and the murder itself. Once more we reject appellant's argument.

The evidence shows and the State stressed during argument that appellant killed Wendy Alba, shot Webb, and attempted to shoot Donoho after breaking into Webb and Donoho's apartment. The court's charge defined capital murder, burglary of a habitation, attempted murder, and murder. Further, the application paragraphs of the court's charge track the indictment. The trial court did not err in overruling appellant's objections to the charge. See points of error one and two, supra.

We affirm the judgment of the trial court. KELLER, J., concurs in point of error six and otherwise joins the opinion of the Court.

BAIRD, Judge, concurring.

Finding myself in disagreement with the treatment of the sixth point of error by both the plurality and the dissent, I write separately. The trial judge denied appellant's request to voir dire, outside the hearing of the jury, the State's expert witness prior to the expert giving his opinion. Tex.R.Crim.Evid. 705(b) provides:

(b) Voir Dire. Prior to the expert giving his opinion or disclosing the underlying facts or data, a party against whom the opinion is offered shall, upon request, be permitted to conduct a voir dire examination directed to the underlying facts or data upon which the opinion is based. This examination shall be conducted out of the hearing of the jury.FN1

FN1. All emphasis is supplied unless otherwise indicated.

In Goss v. State, 826 S.W.2d 162 (Tex.Cr.App.1992), we stated:

Under Rule 705(b), the defendant in criminal trial is undeniably entitled, upon timely request, ‘to conduct a voir dire examination directed to the underlying facts or data upon which the opinion [of the State's expert] is based.’ The trial court must allow this examination to be conducted ‘[p]rior to the expert giving his opinion’ and ‘out of the hearing of the jury.’ ... Because of the mandatory nature of Rule 705(b), a trial judge's denial of a timely and proper motion for such hearing would constitute error. Id., 826 S.W.2d at 168.

Notwithstanding these authorities, the plurality holds the trial judge did not err in refusing appellant's request for such a hearing because the purposes underlying Rule 705(b) “have been fully satisfied.” Ante, 905 S.W.2d at 588. I disagree. Rule 705(b)'s underlying purpose is to allow a party to test the basis of an opposing witness' opinion outside the presence of the jury. But the mere asking of hypothetical questions does not satisfy this purpose. Even though some or all of the State's hypothetical facts may provide a basis for the expert's opinion, appellant was still entitled to determine which hypothetical facts the expert felt were important to the formulation of his opinion. Appellant was further entitled to question whether other experts in that particular field commonly rely upon similar hypothetical facts, Rule 703, or whether the expert was qualified by virtue of his knowledge, skill, experience, training or education to form an opinion based upon those hypothetical facts. Rule 702.FN2 Therefore, the purposes underlying Rule 705(b) were not satisfied. Consequently, under Rule 705(b), and Goss, appellant was absolutely entitled to voir dire the State's expert out of the hearing of the jury and the trial judge erred in refusing appellant's request to do so.

FN2. Additionally, in Goss we noted:

... Affording a defendant the chance to voir dire the State's expert witnesses gives defense counsel the opportunity to determine the foundation of the expert's opinion without fear of eliciting damaging hearsay or other inadmissible evidence in the jury's presence. [citation omitted]. A Rule 705(b) hearing may also supply defense counsel with sufficient ammunition to make a timely objection to the expert's testimony on the ground that it lacks a sufficient basis for admissibility.

Id. 826 S.W.2d at 168.

Having found error, reversal is mandated unless the error made no contribution to appellant's punishment. Tex.R.App.P. 81(b)(2). See also, Goss, supra. The record reveals the thirty six year old appellant forced his way into an apartment by shooting through the door. Laughing, appellant alternatively shot and beat his wife until she died. Appellant then shot and severely injured a second victim. Finally, appellant shot at, but missed, a third victim. Upon leaving the apartment, appellant encountered the apartment manager, and again shot and missed his intended victim. Appellant left the scene and, shortly thereafter, kidnapped two teenage boys, forcing them to drive him to a different town. When the police located appellant, a standoff occurred, lasting several hours. Appellant was taken into custody only after a S.W.A.T. team overpowered him.

Many witnesses testified appellant had a bad reputation for being peaceful and law abiding. Testimony indicated that police responded to domestic violence calls at appellant's home on several occasions and his wife was often bruised. Further, there was evidence of appellant's previous altercations with the police, one of which involved an eighty-five mile per hour chase which ended with appellant asking officers to shoot him. Further, appellant was a disruptive prisoner, tearing up a mattress and clogging drains. Finally, the evidence indicated appellant was previously convicted of delivery of a controlled substance and arrested for indecency with a child, after abusing a twelve year old female.

After reviewing the record in this case, I conclude beyond a reasonable doubt, that the error relating to Rule 705(b) made no contribution to appellant's punishment. Accordingly, I concur in the resolution of the sixth point of error and join the remainder of the opinion. OVERSTREET and MALONEY, JJ., join this opinion.

CLINTON, Judge, dissenting.

In my view the majority opinion adequately addresses none of appellant's points of error in this appeal. I will limit myself to discussion of appellant's sixth point of error. I take the time to write specifically on his sixth point of error because the Court's ratio decidendi is not just barely-intelligible (as is its rationale in disposing of every other point of error in this cause), it is also, from what I can tell, wrong.

During the punishment phase of trial, the prosecutor proffered a lengthy hypothetical question to Dr. Richard Coons, a forensic psychiatrist, to obtain his opinion of the probability appellant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society. Before Coons could answer, appellant interposed a request to voir dire him pursuant to Tex.R.Cr.Evid, Rule 705(b). That request was expressly denied. In his sixth point of error appellant now complains that the trial court erred to deny him this opportunity.

A plurality of the Court holds that, notwithstanding the mandatory language of the rule, denying appellant's request was not error on the particular facts of this case because by the time appellant asked to voir dire Coons, the facts or data underlying his expert opinion were already before the jury in the form of the prosecutor's lengthy hypothetical question. Thus, “the purpose of Rule 705(b) [has] been fully satisfied.” Op. at 588. For an apparently similar reason, the plurality concludes additionally that any error would have been, in any event, “clearly harmless.” Id., at 588. Both of these conclusions are wrong, and for basically the same reason.

It is true that one of the purposes of Rule 705(b) is to test the factual basis of an expert's opinion outside the presence of the jury, in case some of what supports his opinion is objectionable. I agree that by the time appellant asked to voir dire Coons the jury had already heard the facts Coons was to assume in formulating his expert opinion that appellant would be a future danger to society. Under the circumstances, a Rule 705(b) voir dire would be pointless if its only purpose was to elicit the purely factual basis of an expert's opinion in camera. But in my view Rule 705(b) serves other purposes as well, purposes that this Court has recognized before but conveniently ignores today. For Rule 705(b) is primarily a rule of discovery.

For one thing, Rule 705(b) allows the opponent of expert testimony what will often be his first glimpse of the facts and data underlying the expert's opinion, and allows him to challenge its admissibility, if he can, on the basis that those facts or data are insufficient to support the opinion, pursuant to Tex.R.Cr.Evid., Rule 705(c). See Goss v. State, 826 S.W.2d 162, 168 (Tex.Cr.App.1992); Goode, Wellborn & Sharlot, Texas Practice: Texas Rules of Evidence: Civil and Criminal § 705.2, at 71 (2d ed. 1993). It seems to me that by allowing voir dire to reveal “underlying facts or data,” rule 705(b) contemplates discovery of far more than just, as in the present case, the purely historical facts that are to be related to the jury in hypothetical form.

I have elsewhere suggested that Rule 705(c) provides a basis to challenge admissibility of novel scientific evidence that has not been shown to be generally accepted in the relevant scientific community. See Kelly v. State, 824 S.W.2d 568, 577-78 (Tex.Cr.App.1992) (Clinton, J., concurring). I have also been “willing to suppose, because the law supposes, that a psychiatrist may perceive something in the conduct of an accused, disclosed to him in hypothetical form, that from the perspective of his training and experience is revealing as to whether the actor is likely to constitute a continuing threat of violence. See generally Barefoot v. Estelle, 463 U.S. 880, 103 S.Ct. 3383, 77 L.Ed.2d 1090 (1983).” Flores v. State, 871 S.W.2d 714, 725 (Tex.Cr.App.1993) (Clinton, J., dissenting). But just because the law tolerates admission of expert testimony of the kind at issue here does not mean appellant should not be permitted, as part of the discovery that Rule 705(b) contemplates, to adduce not just the factual, but also the psychiatric, basis for the expert's opinion. Under Rule 705(b) an opponent of psychiatric expert testimony ought to be allowed to inquire precisely what it is about an accused's past conduct that would lead a forensic psychiatrist to conclude he will continue to commit violent acts in the future.

Despite the fact that the United States Supreme Court accepted the judgment of the American Psychiatric Association that psychiatric predictions about extended future dangerousness are wrong “most of the time,” it did not find those odds constitutionally unacceptable. Barefoot v. Estelle, 463 U.S. at 901, 103 S.Ct. at 3398, 77 L.Ed.2d at 1109. As far as I know, however, this Court has not yet decided whether such predictions are so unreliable that they might be objectionable as a matter of state law, under Rule 705(c). See Fuller v. State, 829 S.W.2d 191, 195 (Tex.Cr.App.1992) (question whether psychiatric testimony regarding future dangerousness is objectionable under, inter alia, Rule 705(c), was not reached because it was “neither well presented by the trial record nor well joined in the appellate briefs.”). By cutting off appellant's right to voir dire Coons, the trial court preempted his opportunity to make such an argument in this cause.

Even if a trial court does not find psychiatric testimony of future dangerousness to be inadmissible under Rule 705(c), the opponent of that testimony may find voir dire of the psychiatrist as permitted by Rule 705(b) to be a useful discovery tool in other respects not contemplated by the plurality. For example, if the psychiatrist deduces nothing from the facts of the hypothetical that a layman cannot as readily deduce on his own, his testimony may be objectionable as not “helpful” under Rule 702. See Barefoot v. Estelle, supra, U.S. at 934, n. 13, S.Ct. at 3416, n. 13, L.Ed.2d at 1130-31, n. 13 (Blackmun, J., dissenting) (notorious forensic psychiatrist Dr. Grigson contends that “most of these things are so clearcut [the man on the street] would say the same things I do.”); Kelly v. State, supra, at 575 (Clinton, J., concurring) (Rule 702 allows expert testimony when it proves or illuminates “an elemental fact (or some evidentiary fact leading to an elemental fact) in a way not readily apparent to a jury of laymen without that knowledge.”). The opponent of psychiatric testimony will certainly prefer to avoid the risk of exploring this avenue for the first time on cross-examination. Rule 705(b) seems to afford him that opportunity. Moreover, even assuming the expert's testimony is “helpful,” and thus not objectionable under Rule 702, the opponent may wish to explore the psychiatric basis for the expert's opinion out of the jury's presence so that he can decide whether, and if so, how best, later to cross-examine the expert in the jury's presence in an effort to assail the weight of his opinion. In my view Rule 705(b) grants him this option for discovery as well.FN*

FN* The plurality speculates that what I am “really ... upset about is allowing expert opinions, like the one here, in cases like this.” Op. at 589, n. 10. That the plurality should cite my dissent in Flores for this is a puzzle to me, for I readily conceded there that expert opinions of future dangerousness premised upon hypothetical questions are not per se objectionable. 871 S.W.2d at 725. My point here is that in the individual case there may be something objectionable about the psychiatric basis for this sort of testimony, either under Rule 705(c) or Rule 702, and that Rule 705(b) should be read to grant an accused an opportunity to explore these avenues of objection outside the presence of the jury. If, for instance, a psychiatrist admits that he is in no better position than a layman to infer from hypothetical facts that an accused will constitute a future danger to society, he should not be allowed to give an opinion on that matter because his opinion will not “assist the trier of fact” for purposes of Rule 702. A capital accused ought to be allowed to elicit such an admission before the jury is subjected to an “expert” opinion it will only have to disregard. Rule 705(b) provides that opportunity. Somehow the plurality gleans from this that what I really want is “to bring back the old discredited objection that ... expert testimony ‘invades the province of the jury.’ ” Op. at 589, n. 10. I should by no means be understood to advocate that.

From this apparent misunderstanding of my purpose, the plurality launches into a diatribe about how it is actually the Court itself that invades the province of the jury every time it holds evidence insufficient to support a jury finding of future dangerousness. The plurality suggests that instead we should always defer to a jury finding of future dangerousness by virtue of nothing more than the fact that the accused has already been found guilty of capital murder. While it is true enough that we frequently iterate that the facts of the capital offense may in themselves be sufficient, we have yet to hold they invariably are. Because sufficiency is not the issue in this case, the plurality's marginal remarks are wholly gratuitous, and should, of course, be recognized for the dicta that they are. But they are dangerous dicta indeed.

In addition, the plurality opines that any error was “clearly harmless.” Op. at 588. The plurality does not say so, but I suspect the lack of harm seems “clear” to it because appellant had already heard the historical facts upon which Coons was to base his opinion in the hypothetical question itself, before appellant ever requested a Rule 705(b) voir dire. (Indeed, the historical facts were in evidence before the hypothetical question was propounded.) But the plurality is mistaken to think that the “underlying facts or data” contemplated by Rule 705 could only consist in this context of historical facts that go to make up a hypothetical question. Appellant was also entitled to discover, under Rule 705(b), and to challenge, if he could, under Rule 705(c) or Rule 702, the psychiatric basis for concluding from those historical facts that he would constitute a continuing threat to society. The plurality does not ask itself whether failure to allow this discovery may have proven harmless.

Moreover, the harm analysis the plurality does purport to conduct is flawed. Echoing Goss, the plurality declares that, once it identifies error in failure to afford the voir dire Rule 705(b) guarantees upon request, “a reviewing court would then be required to decide whether the trial judge's error was so harmful as to require reversal.” Op. at 588, citing 826 S.W.2d at 168. If this is meant to be an articulation of the harmless error rule codified in Tex.R.App.Pro., Rule 81(b)(2), then it erroneously places the burden of persuasion on appellant rather than the State. The question under Rule 81(b)(2) is not whether “the error was so harmful as to require reversal.” Rather, the question is whether the State, as beneficiary of the error, can persuade us to a level of confidence beyond a reasonable doubt that the error made no contribution to the affirmative answers to the special issues. Arnold v. State, 786 S.W.2d 295, 298 (Tex.Cr.App.1990). In other words, the presumption is that the error was harmful until the State satisfies us otherwise. If we cannot tell whether error was harmful or not, we must conclude that it was; that is what it means to say the State has the burden of persuasion on this issue.

We cannot tell whether the failure of the trial court to allow the voir dire of Coons, pursuant to Rule 705(b), contributed to the jury's affirmative answers to the special issues in this cause or not. Appellant may have been able to attack the admissibility of Coons' opinion testimony as either unsupported by sufficient facts or data, under Rule 705(c), or as unhelpful, under Rule 702. Or, he might simply have gained sufficient knowledge of the psychiatric basis for Coons' opinion that he could efficaciously impugn it on cross-examination. On the other hand, he might ultimately have accomplished nothing. Because he was never afforded the opportunity for discovery that Rule 705(b) guarantees, we can never really know whether he might have succeeded in these attempts, or even, indeed, whether he would have tried. But precisely because we cannot know, we are not at liberty to conclude, consistent with a proper understanding of the assignment of the burden in Rule 81(b)(2), that the error was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Court should at least vacate the judgment in this cause and remand it for a new punishment hearing under Article 44.29(c), V.A.C.C.P. Because the Court does not even do this, I dissent.

Alba v. Thaler, 346 Fed.Appx. 994 (5th Cir. 2009). (Habeas)

Background: Following affirmance of his conviction in state court for capital murder, 905 S.W.2d 581, and affirmance of his death sentence after retrial on issue of punishment, 2003 WL 1888989, state prisoner filed federal petition for writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, Marcia A. Crone, J., 621 F.Supp.2d 396, denied the petition. Petitioner sought certificate of appealability (COA).

Holdings: The Court of Appeals held that:

(1) petitioner failed to establish good cause for failing to raise his claim that prosecutor's decision-making was rooted in racial bias, and

(2) failure to consider habeas petitioner's procedurally defaulted claim would not constitute a miscarriage of justice. COA denied.

FN* Pursuant to 5th Cir. R. 47.5, the court has determined that this opinion should not be published and is not precedent except under the limited circumstances set forth in 5th Cir. R. 47.5.4.

Texas inmate John Alba (“Alba”) seeks a certificate of appealability (“COA”) to appeal the district court's denial of his petition for a writ of habeas corpus. Because no reasonable jurist could disagree that Alba's claims are procedurally defaulted, we deny the COA.

The details of Alba's 1991 murder of Wendy, his wife, are set forth in Alba v. State, 905 S.W.2d 581 (Tex.Crim.App.1995), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 1077, 116 S.Ct. 783, 133 L.Ed.2d 734 (1996). The district court described the procedural background:

On November 19, 1991, Alba was indicted for capital murder under Section 19.03(a)(2) of the Texas Penal Code for intentionally committing murder during the course of a burglary. Alba pleaded not guilty. On May 7, 1992, after being found guilty at a jury trial, he was sentenced to death. His conviction and sentence were affirmed on direct appeal. See Alba v. State, 905 S.W.2d 581 (Tex.Crim.App.1995), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 1077, 116 S.Ct. 783, 133 L.Ed.2d 734 (1996). Alba then applied for a writ of habeas corpus, which the state court denied. See Ex parte Alba, No. 36711-01 (Tex.Crim.App. Apr. 15, 1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 967, 119 S.Ct. 414, 142 L.Ed.2d 336 (1998). On August 21, 2000, however, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit vacated Alba's death sentence. See Alba v. Johnson, 232 F.3d 208 (5th Cir.2000). Alba was then retried on the issue of punishment only. On March 1, 2001, he was again sentenced to death. His death sentence was affirmed on direct appeal. See Alba v. State, No. 71487, 2003 WL 1888989 (Tex.Crim.App. Apr.16, 2003), cert. denied, 541 U.S. 1065, 124 S.Ct. 2390, 158 L.Ed.2d 966 (2004). He then sought a writ of habeas corpus in state court, which was denied. See Ex parte Alba, No. 36711-02 (Tex.Crim.App. Oct. 15, 2003).